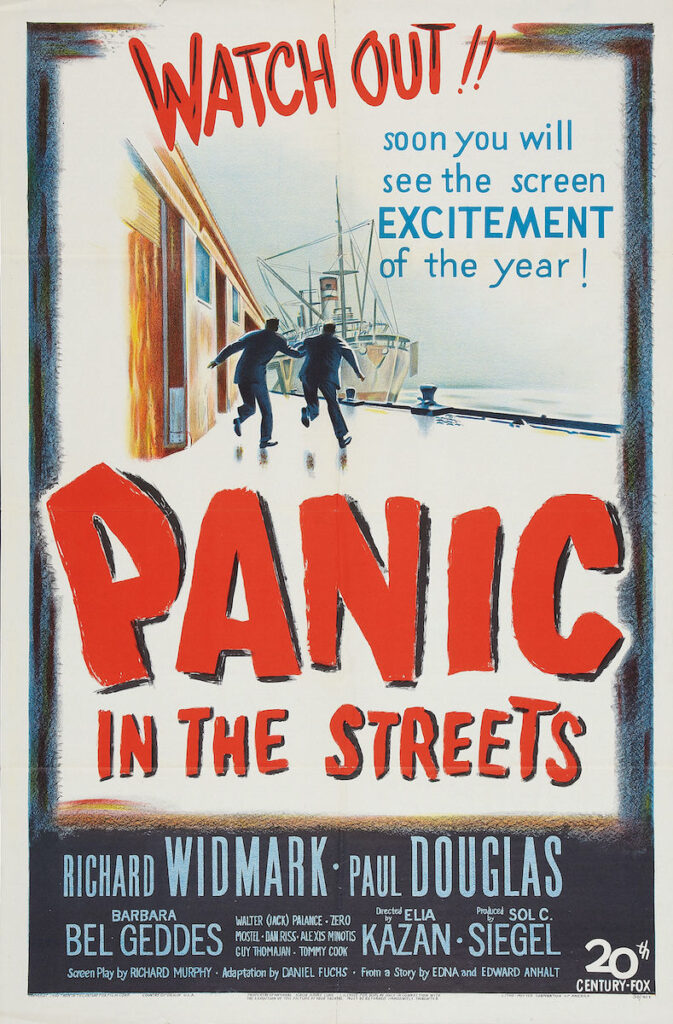

In mid-March, as the number of COVID-19 cases grew and cities and states implemented social-distancing regulations, so many people streamed the 2011 disease disaster movie Contagion that it became the top film on Netflix. Instead of streaming Contagion, I decided to pull from my DVD shelf a 1950s film noir, Panic in the Streets. This story of “a silent, savage menace” and the people fighting to stop it mirrors the current pandemic and the issues of stigma, community, and authority we are confronting with COVID-19.

The film opens with gangsters Blackie (Jack Palance) and Raymond Fitch (Zero Mostel) gunning down a visibly ill man named Kochak, who has just arrived at the port of New Orleans and has the unfortunate luck of beating the villains in a card game. When the police fish the dead man’s body from the delta the next day, they assume he will be just another John Doe murder victim. But when the coroner finds evidence of pneumonic plague during the autopsy, he calls in the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS).

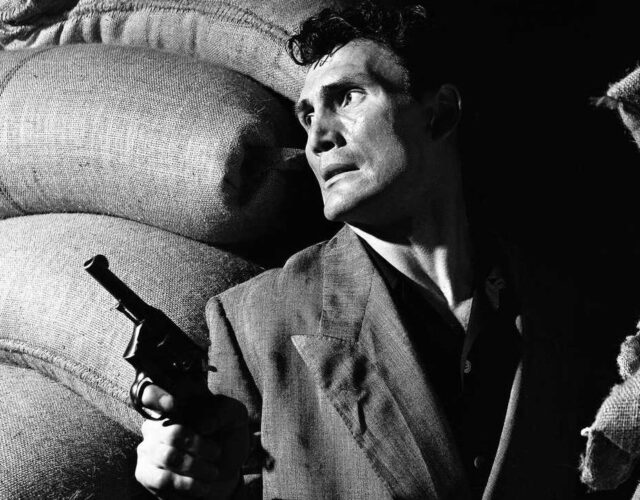

Unlike the bubonic and septicemic plagues, which are spread through flea bites, pneumonic plague spreads from person to person through airborne droplets: Kochak was, and now his murderers are, possible spreaders of the disease. This discovery sets off a 48-hour, ticking-clock plot as Clinton Reed (Richard Widmark), a doctor and lieutenant commander in the USPHS, traces the path of the murdered man with the assistance of his police liaison, Tom Warren (Paul Douglas), in an attempt to find the killers before they become infectious and kick off an epidemic.

The conventional manhunt plot belies the complex issues of illness, immigration, community, and authority at the core of the movie. New Orleans and its real-life residents, who fill all but 12 of the 112 speaking roles, provide the foundation for these themes. The port city was a trade crossroads with a significant immigrant population and a history of infectious disease outbreaks. By using local settings and people and deploying a semidocumentary style that evokes the patriotic newsreels of the late 1940s, director Elia Kazan establishes a degree of realism and a sense of place. Viewers find a hub of international trade—a packed union hall, a merchant ship with a multinational crew, an immigrant-owned restaurant, a coffee warehouse.

But these same atmospheric elements are also used to traffic in some nasty stereotypes.

In the United States immigrants had long been accused of harboring diseases and were stigmatized as sources of infection. As a result New Orleans and other port cities were viewed as points of entry for yellow fever, smallpox, cholera, and other illnesses. (This xenophobia persists, a recent example being the White House’s use of the coronavirus outbreak to justify closing the country’s borders to immigrants.) Kazan plays directly to such fears by having Kochak, an undocumented immigrant, carry pneumonic plague to New Orleans and spread it among the town’s underworld and immigrant communities.

In real life the chances of someone with pneumonic plague making a transatlantic voyage without displaying symptoms or dying is virtually zero. Debilitating symptoms—including high fever and weakness—often begin within a few hours of infection, and if left untreated, the disease can cause respiratory failure within two days. Kochak isn’t developed as a character; rather, he’s an embodiment of the unwarranted fear of “disease-carrying” immigrants. This character’s marginal status and the port setting work together to establish an atmosphere of strangeness and threat that would have been immediately evident to Kazan’s target audience—white Americans.

Likewise, Kazan’s stylistic approach blends realism, which gives the film a sense of immediacy, and stereotyping, which puts into relief the virtue of authority figures Reed and Warren, whose efforts to prevent a plague outbreak are met with skepticism and resistance. City officials and police officers are reluctant to believe Reed’s dire predictions of unchecked spread. The sailors and immigrants he questions are resistant to sharing information or to being inoculated; their suspicion of government authority makes them wary of offering information on Kochak or his movements.

As a USPHS officer Reed can compel those exposed to the disease to undergo treatment or be locked up under quarantine, but he cannot force anyone to provide evidence or seek medical help. He cannot overrule local government officials or force them to close roads, airports, or docks. In these moments where Reed reaches the limits of his power, the film resonates with the modern viewer. Reed, like today’s public health officials, must rely on persuasion to convince people to fight the outbreak. Multiple times Reed implores others to take him and the disease seriously or face an epidemic.

The spread of plague within New Orleans is not Reed’s only concern. He fears news of a possible outbreak will create panic and trigger a flight of plague-carrying residents from the city. To prevent that, Warren, the police liaison, locks up a journalist to keep the news under wraps; he knows the arrest and imprisonment are illegal, but he does it anyway to prevent mass panic. After the mayor frees the journalist and announces that the reporter’s story will run in the next day’s paper, Reed begs them to reconsider. He reminds them that an outbreak will not be confined to New Orleans:

For the impassioned Reed the threat of pandemic is a greater risk than keeping the public in the dark or trampling on a few constitutional rights.

So how do we balance individual rights and public health concerns? What information should health professionals and governments share with the public? How can authorities provide understandable, accurate medical content without causing panic? Reed wants to keep the public in the dark, while the mayor wants to provide people with a medically accurate fact sheet. The audience never knows if the public finds out about the plague, and if so, how they respond. We never know if any actual “panic in the streets” occurs.

Kazan’s sympathies are with Reed and his plan to stop the plague, but he also respects the role of institutions and their importance in public life. Panic in the Streets avoids the trope of one man bucking the system and triumphing. Reed is not perfect, his actions are not above reproach, and he does not stop the outbreak by himself. In fact Reed is never alone on screen. In each scene there is always someone by his side—his wife, Warren, police officers, or USPHS doctors—finding and processing clues with him.

In these ways the film succeeds in showing the messy reality of disease control and prevention: difficulties tracing who might be exposed, government officials arguing about who is in control, and debates about how to share information with the public without creating panic.

As I rewatched Panic in the Streets, I was surprised by how relevant the 70-year-old film is in our current moment. The earliest American hot spots for COVID-19 were hubs of travel and trade. The world has become more tightly interconnected since the movie was made, allowing an epidemic to swiftly turn into a pandemic. Reed’s speech about air travel and how quickly someone could reach Africa grabbed me: I had just returned from a conference in South Africa when the United States began shutting down. In 14 hours I went from Johannesburg to Atlanta to Philadelphia. If I was sick with COVID-19, I could have exposed hundreds of travelers, who then could have carried the disease on to their destinations.

While travelers of all sorts carry germs with them around the globe, immigrants are still often singled out as the source of disease in the United States and elsewhere. The White House, conservative media outlets, and social media have fanned the flame of this long-standing stigma. The result has been racist attacks, particularly against Asian Americans, including threatening graffiti, verbal abuse, and physical assault, that have spiked since February. While medicine, media, government policy, and social norms have all changed significantly in the past 70 years, we still have not discarded the shameful narrative connecting immigrants with disease that is central to the movie’s plot.

Kazan wanted to show the messy but ultimately successful work of American institutions. Yet the persistence of racist stereotypes and anti-immigrant scapegoating shows how our civic systems failed immigrants in the past and continue to do so in the present. A critical viewing also reveals other elements of ingrained racism and inequality. While the movie is shot in a 1950s Southern city, there are no overt signs of segregation. There are no scenes with separate drinking fountains or building placards prohibiting people of color. Instead, there is a noticeable absence of Black people in the film, especially in speaking roles. The film was cast with locals to reflect the diverse nature of New Orleans, but it omitted almost 30% of the population, excising a significant part of the city’s culture.

In the film authority figures clash, citizens resist, and some civil rights get temporarily revoked. Ultimately, though, the movie shows audiences that when faced with a health crisis, local and federal systems can prevent or manage an outbreak. But while Kazan’s film is designed to instill confidence in civic institutions, the truth is those institutions have long failed many communities. Those neglected and mistreated include Black Americans, Native Americans, members of the LGBTQ+ community, people with disabilities, and people living unhoused, all of whom have faced and still face discrimination in our health-care systems. The film’s vision serves a middle-class white audience, the same audience these institutions were made to serve.

In our current pandemic moment we see more clearly how racism infects our medical and public health systems. African American, Hispanic, and Native communities have disproportionately high rates of COVID-19, the result of generations of inequity that has exposed racial minorities to harmful environmental factors and left them with poor access to health care. During the recent Black Lives Matter protests, activists and health care providers have laid bare the institutional racism that pervades American medicine. These modern message makers seek to reimagine the racist system Kazan celebrated. They are showing how systemic, race-based health disparities are killing Black Americans, and they are asking white Americans to join them in the fight to remake our health-care system into one that serves all equally.