In 1927 Adolf Dessauer, a German doctor, was vacationing in Italy with his wife, Lilly, when they met an artist named Franz Wilhelm Voigt. The physician was pleased to learn that a number of years earlier Voigt had painted a portrait of the physician and scientist Paul Ehrlich for a magazine article. Adolf, who had briefly worked under Ehrlich and held him in great esteem, commissioned Voigt to reproduce the portrait as an oil painting.

Adolf’s purchase was notable in part because the frugal doctor had no particular love of art; the family had only one other painting, of a lobster, in their Nuremberg apartment. Adolf’s son Rolf recalled recently, “I am sure he admired Ehrlich. I mean, he admired him enough to buy a painting. Knowing my father, that’s a lot of admiration.”

Ehrlich was Jewish, as was Adolf, and a paragon of Jewish scientific achievement in the face of deeply ingrained institutional anti-Semitism. Ehrlich had declined to convert to Christianity despite the harm to his career. He was denied full credit for helping develop a diphtheria serum at the Charité hospital in Berlin, although the achievement earned his non-Jewish collaborator a Nobel Prize. But Ehrlich soldiered on. He ran a research institute in Frankfurt, discovered a treatment for syphilis, and finally earned his own Nobel in 1908. He died in 1915.

“It was a kind of triumph against adversity. He was viewed as somebody who had heroically faced the anti-Semitism at the Charité,” says Liliane Weissberg, a professor of German and comparative literature at the University of Pennsylvania. “For the Jewish population he was not just a person who won a medical award but a person who was steadfast against obstacles and succeeded in making a name.”

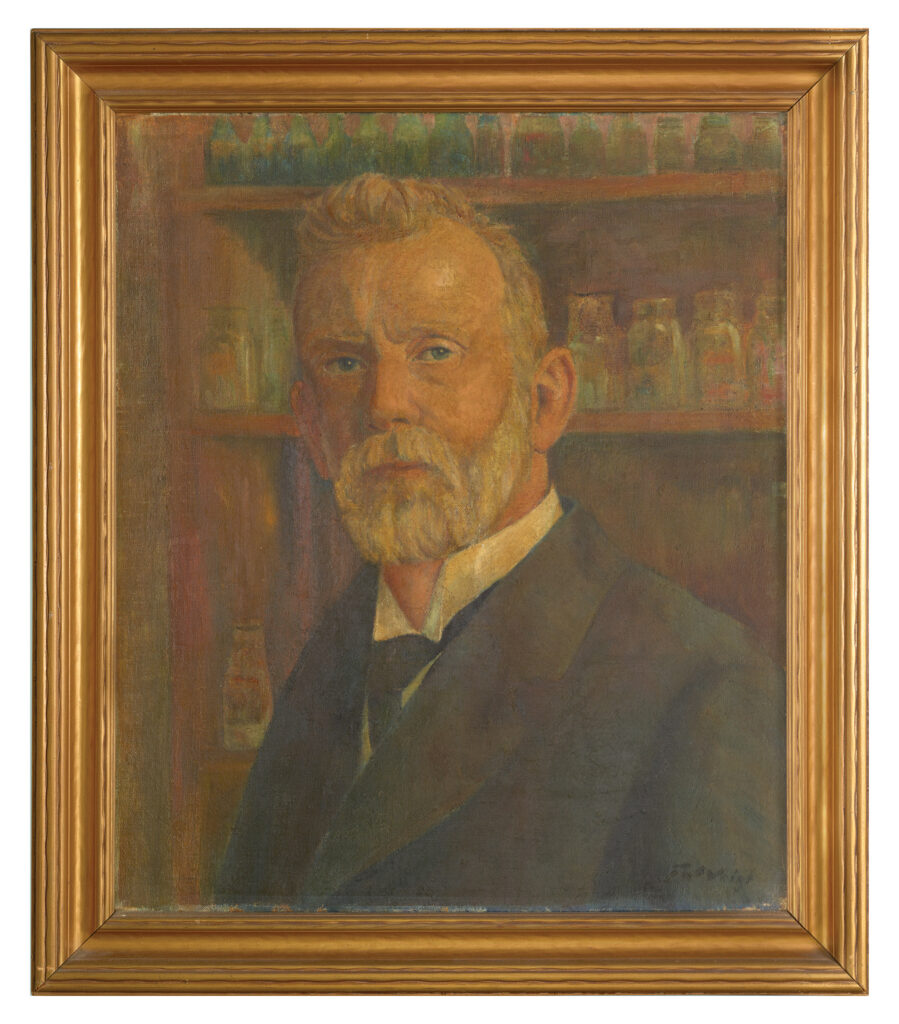

Portrait of medical pioneer Paul Ehrlich painted by German artist Franz Wilhelm Voigt, 1927.

Adolf Dessauer was “totally irreligious,” according to Rolf, but Ehrlich was still a hero to him. “Ehrlich was a nice Jewish guy who made a significant contribution,” he said. “I assume there was a certain pride in [his being] a Jewish physician. I think that’s why my father got this painting.”

Three years ago Rolf, who had a successful career as a chemist at DuPont, gave the portrait to CHF. But the painting he donated is different in crucial ways from the piece his father bought 90 years ago. It still radiates the symbolic, defiant pride that Adolf treasured in Ehrlich, but it also bears, in its canvas, paint, and varnish, the great horrors and small triumphs of the succeeding years.

Eleven years after the Dessauers’ trip to Italy, on the night of November 9, 1938, Nazi storm troopers gathered in the main city square of Nuremberg and set off on a rampage. They set fire to a synagogue, attacked Jews in the street, raided homes, and committed several murders.

In an apartment on Pfalzerstrasse, 12-year-old Rolf woke around 2:00 a.m. to hear his mother pleading with several members of the Sturmabteilung, or SA, the notorious brown-shirted Nazi paramilitary organization. She went upstairs to ask a neighbor to attest to the Dessauers’ good character in the hope of persuading the SA to leave, but the neighbor refused to come down.

As Rolf recalls the event, a gathering crowd of about 25 Brownshirts, some of them drunk, ordered the family into the street and set to the home with mallets, smashing furniture and turning closets inside out. The Dessauers returned to find the apartment ruined and in darkness owing to an electrical short circuit. They also noticed the SA had missed the dining room, where Adolf kept valuable medical equipment. They hurriedly pushed a bookcase against the door to hide the entrance to that room.

At 2:45 a.m. more SA thugs arrived to find there was nothing left for them to destroy. “Haben Sie Geld?” a storm trooper demanded. “Do you have any money? Give it to me.” He took 500 Reichsmark, worth $200 at the time, or about $3,400 today, Rolf says. More Nazis came at 3:30, and at 4:00 a.m. three SA leaders came by to inspect the damage. The police arrived at 4:30 a.m. to ask if the Dessauers wanted to file a complaint. They did not. The SA never found the dining room or the medical equipment.

The coordinated nationwide attacks on Jews and their businesses and institutions came to be known as Kristallnacht, the “night of broken glass.” It was a horrifying turn in the Nazi policy of anti-Semitism that later led to the Holocaust.

The Ehrlich portrait had been “slashed to ribbons” and put in the trash, according to Rolf. But the next day the family was visited by a local man who had heard about the damage and offered to restore the painting. Two days later he returned the piece, wrapped in newspaper and nearly as good as new. The Good Samaritan’s name is lost to memory, but the Dessauers never forgot what he did for them.

“He was a good-looking blond man, about 40, who looked like all the Aryans on posters,” Rolf recalls. “He refused to take money and told my father he wanted it to be known that not all Germans supported Kristallnacht. I distinctly remember the entire experience because my father was happy.”

Even before Kristallnacht the Dessauers had seen the writing on the wall and had been planning to leave Germany. Rolf’s older brother, Heinz, had emigrated to New York the previous year, and Adolf followed him a month after the apartment raid. The following May, Rolf and his mother were finally able to depart as well. The Nazis took almost all of their money, but the family was allowed to ship a large crate of belongings to the United States, including furniture, medical instruments, dishes, and the painting. Many other Jews could not afford to leave or didn’t recognize their peril until it was too late. Adolf’s brother and his family, as well as Lilly’s mother, stayed behind, in part because finding Americans willing to provide immigration affidavits was very difficult. All of them later died in the Holocaust.

The Dessauers went to New York because many other states barred noncitizens from working as physicians. While Adolf prepared for English-proficiency and medical licensing exams, the family lived in cramped poverty in Washington Heights, subsisting on Heinz’s pay as a shipping clerk and Lilly’s meager earnings from cleaning houses and cutting watch crystals in a factory. In 1942 Adolf finally passed the state board exam, and the Dessauers moved to Flushing, where he opened a practice in their home. He subsequently changed the spelling of his name to Adolphe.

The medical practice prospered, but Rolf still shakes his head at the intolerance common among state medical boards, many of which placed insurmountable hurdles before foreign doctors hoping to work in the United States or banned them entirely. “What would our medical system be like right now if all these Indians and Pakistanis couldn’t be practicing?” he says, referring to the many American doctors of South Asian origin. “Immigrants have helped this country immensely.”

Rolf attended public school and repeatedly visited the 1939 World’s Fair, where he became fascinated by a DuPont exhibition on the achievements of industrial chemistry. He was given a free pass to the Museum of Modern Art and gained a lifelong love of modern painting and sculpture. He served in the U.S. Army, earned a PhD in organic chemistry at the University of Wisconsin, and worked at DuPont for 39 years, focusing on dyes and photochemistry. His work on biimidazole chemistry led to the widely used Dylux line of photo-proofing products. For decades printers used Dylux to create instant blue-toned proofs—known as bluelines—they could review for errors before making final prints, a process that saved them time and money.

The Ehrlich portrait hung in Adolphe’s office and, after he died, in Lilly’s apartment. When she passed away in 1983, Rolf hung it in his house outside Wilmington, Delaware. Time seems to have taken a toll on the painting; it’s fairly dark, possibly from aging varnish, with Erhlich’s black suit jacket and shadowy laboratory shelves filling much of the canvas.

But amid the gloom the viewer’s eye is drawn to the subject’s thoughtful, penetrating gaze. It’s all the more noticeable because Voigt left out Ehrlich’s glasses, in a departure from the original magazine illustration and most photographs of the scientist.

If you look at the painting even more closely, the vestiges of Kristallnacht—or more precisely, of the subsequent restoration— become subtly visible. CHF researchers have noted a smoother texture over Ehrlich’s cheek, perhaps from the restorer’s overpainting. They found seams and ridges down the nose, along the right side of the face, and elsewhere, which are probably evidence of mended lacerations. One trace appears circular, as if a storm trooper had punched a hole through the painting’s center.

“If you look at where the damage is concentrated and how many areas of damage there are, you realize they attacked his face. They didn’t stab him in the shoulder; they attacked his personhood,” says Elisabeth Berry Drago, a public-history fellow at CHF. “The damage is revealing of more than just that it happened on Kristallnacht. It tells you exactly how it happened.”

Rather than detracting from the portrait, those traces of November 1938 seem to have added to its emotional power. It is not only an image of an inspiring Jewish scientist but an embodiment of the violence a family endured and the kindness that redeemed part of that injury. Kristallnacht was a terrible trauma and created “horrible uncertainty” for Jews, Rolf said, but the painting’s near-destruction also created the opportunity for a small moment of heroic sympathy.

“My father was very happy with this German man who repaired [the painting], and I think it was probably the idea that somebody endangered himself to go and visit a Jewish house and repair something that the Nazis had made so much effort to destroy,” he says. “If they had found out that he had done this, he probably would’ve wound up in the concentration camp.” Rolf believes his father appreciated the painting “as a reminder of things past.”

“It’s not just a painting that has decayed naturally,” Weissberg says. “The painting is evidence of history in many ways. It’s a document.”

Signs of disrepair and deterioration can have emotional resonance. Nicole Cook, CHF’s fine-art researcher, gives the example of a child’s teddy bear, whose sewn-up ears and mismatched buttons give it unique sentimental value. In the same way, the portrait’s scars put it in a class of objects enriched by the vicissitudes of the past.

“Investigating why this is cracked, why this is torn, why this is discolored tells you not just about the history of the object but the history of the people who made and used it,” Drago says. “If you studied this painting but you didn’t study the damage done to it, you would in no way understand its importance either to a family or to history. The damage is revealing of the whole period in which it was created, the story of who it was created for, and why they held onto it.”