Leave It to Beaver and Dragnet might come to mind when you think about American TV during the 1950s, or maybe Edward R. Murrow challenging McCarthyism. But likely not factory tours. Yet week after week throughout the decade, West Coast TV viewers could spend their Friday evenings following genial TV hosts through humming local plants as they met skilled workers and marveled at the wonders of technology. These viewers were unwitting participants in an elaborate scheme to sell bulk petroleum products to major industrialists.

TV was in a growth spurt in 1955. Lots of people had bought their first set, but televisions were not yet ubiquitous. Programming was limited, and people didn’t yet watch habitually. Commercial stations searched for ways to make broadcasting profitable, while sponsors sought audiences through experimental programming.

Success Story, sponsored by the Richfield Oil Company of California, was one of these experiments. In a typical half-hour episode the cheerful host escorts viewers around the factory floor of a thriving local organization, usually an industrial firm, introducing the CEO, meeting employees who operate complex machines, and showing the manufacturing process in action. Producing the show involved a 25-person on-site film crew and extensive cooperation between a firm’s management and representatives of Richfield Oil in order to find interesting visuals and craft a script.

If the program sounds somewhat less exciting than an episode of Dragnet, you’d be right. But broadcasting the TV show was (almost) beside the point. Richfield’s true goal was building relationships with major industrialists on the West Coast. These “blue-chip prospects” supervised bulk purchases of petroleum products and often became loyal Richfield customers after appearing in Success Story, as Sponsor Magazine revealed in 1957. (As a public service, and maybe to improve its cover, Richfield made sure a quarter of the show’s episodes featured a charity or community group, like the 1957 program on the Athens Water Follies, a synchronized swimming “aquacade” in Oakland, California.)

A thin folder tucked inside the massive Beckman Historical Collection in the CHF archives suggests what major industrialists gained from participating in Success Story. Amid publicity materials and correspondence, heavily edited scripts reveal how companies used this uncritical platform to celebrate their products and recruit potential employees.

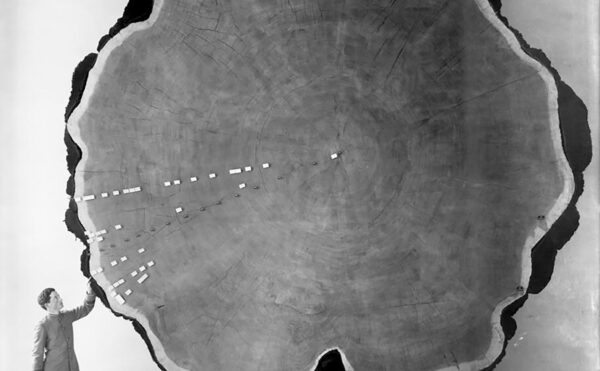

Like TV itself, Beckman Instruments was experiencing a growth spurt in 1955. The firm had recently gone public and had built a huge new factory atop the former citrus groves that had given Orange County its name. Beckman had pioneered the use of electronics in chemical measurement, selling thousands of pH meters, spectrophotometers, oxygen meters, and electronic components. The instruments made analytical chemistry cheaper, faster, and increasingly pervasive. Beckman dreamed of integrating instruments with computers to produce fully automated factories.

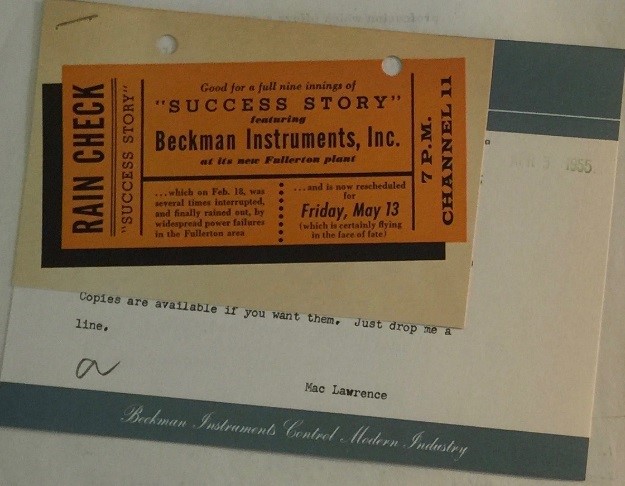

Beckman Instruments was to be featured on Success Story on February 18, 1955. But heavy rainstorms in the Fullerton area caused repeated power outages, and the broadcast was canceled partway through. The company mailed out 25,000 “rainchecks,” looped with red string to hang over the TV tuner, announcing the broadcast had been rescheduled for Friday, May 13—“flying in the face of fate,” as the cards put it cheekily. The Beckman employee newsletter Feedback announced “Success Story—Round Two” over a cartoon boxing match between the Beckman logo and a tough-looking television console. For departments that would be featured in the broadcast, the day’s work schedule was changed, from noon to 8:30 p.m. Employees got a free dinner of fried chicken or fish.

The program opens with a narrator marveling at the “tremendous force of the atom” and the “infinite depths of space.” Beckman’s complex instruments extended human senses into these alien realms and required remarkable expertise to produce. After a Beckman executive demonstrates some of the instruments, the camera cuts to skilled glassblowers constructing a phototube at the heart of an infrared spectrophotometer. The host, Ken Peters, interviews a woman identified only as Mrs. Orison, building a tiny receiver assembly for a thermocouple.

Peters: Doesn’t it make you nervous?

Orison: Oh, no, in fact the successful results are a great feeling of achievement.

Peters: You never feel like going home and beating your husband, then?

Orison: Oh, not for this!

The show features other skilled men and women cutting quartz prisms for spectrophotometers, producing metallic coatings inside vacuum chambers, and wiring automatically controlled instruments.

About two-thirds of the way into the episode Peters introduces Arnold Beckman. In an early draft of the script Peters had originally proposed to ask Beckman about “some very significant social aspects related to automation.” In 1955, as now, automation posed a significant threat to established patterns of employment. In the version ultimately broadcast Peters merely asked Beckman to offer a statement about career prospects to the “good number of young people looking in tonight.” The camera flatters Beckman by zooming in toward his face as he says, “I’m probably a little biased, but I can think of a field no more fascinating than that of electronics, instrumentation, and automation. These fields offer the same sorts of frontiers which our forefathers had in the geographical frontiers.”

The program concludes with this optimistic and uncritical language, celebrating the “Beckman tradition of individual control and perfection” and praising the company and its employees for showing “a purpose that seems to typify the industrial and scientific spirit of America.”

While several hundred episodes of Success Story were aired during the 1950s, very few are accessible today. Companies could order kinescope recordings for their own use, and the clip we’re sharing here comes from a copy that Beckman Instruments kept for educating its salesmen. Two other full episodes of Success Story can be viewed online. One shows off the Ampex Corporation, a pioneer manufacturer of magnetic tape for recording sound and aviation data. Another episode takes the audience inside the Sawyer Viewer factory, where the handheld personal slide viewer, now a classic nostalgia piece, was made for kids.