Imagine one day your husband turns to you with a question about work. He is working long hours, maybe too long hours, but at least he’s finally in a job he likes in this new country, America. He’s dragged you here because there are more opportunities for a biological researcher than in your native Greece. But the start has been difficult—neither of you speaks much English and you have little money, having arrived in 1913 with barely more than $250.

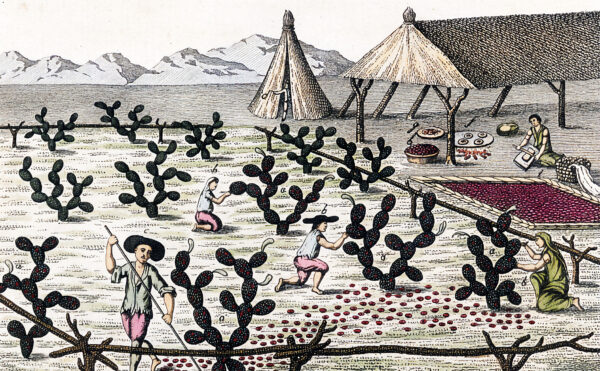

After some wrangling, your husband, George, has landed an assistant position in a laboratory at Cornell Medical College in New York City, where he’s doing something or other with guinea pigs. Drunken guinea pigs, no less, since the lab mainly investigates the damage alcohol might do to chromosomes. George is excited because he’s figured out he can use a human nasal speculum to collect vaginal fluid from guinea pigs. If he puts a smear of the fluid under a microscope, the cells tell him much about the animal’s health and reproductive status. It has him wondering whether this could work with humans, too.

He asks you, his wife, Mary, whether he could do to you what he does to the rodents. As you ponder this question, neither you nor George can guess how many lives will depend on your answer.

Researchers will later estimate that every day about 100 women die of cervical cancer in the United States during the early 20th century. It’s one of the deadliest cancers because it’s one of the stealthiest. Cervical cancer grows slowly and causes few symptoms early on. By the time there is bleeding or pain, the cancer often has already spread to the lungs, bones, or liver. The women grow jaundiced, suffer fractures, cough up blood, then die.

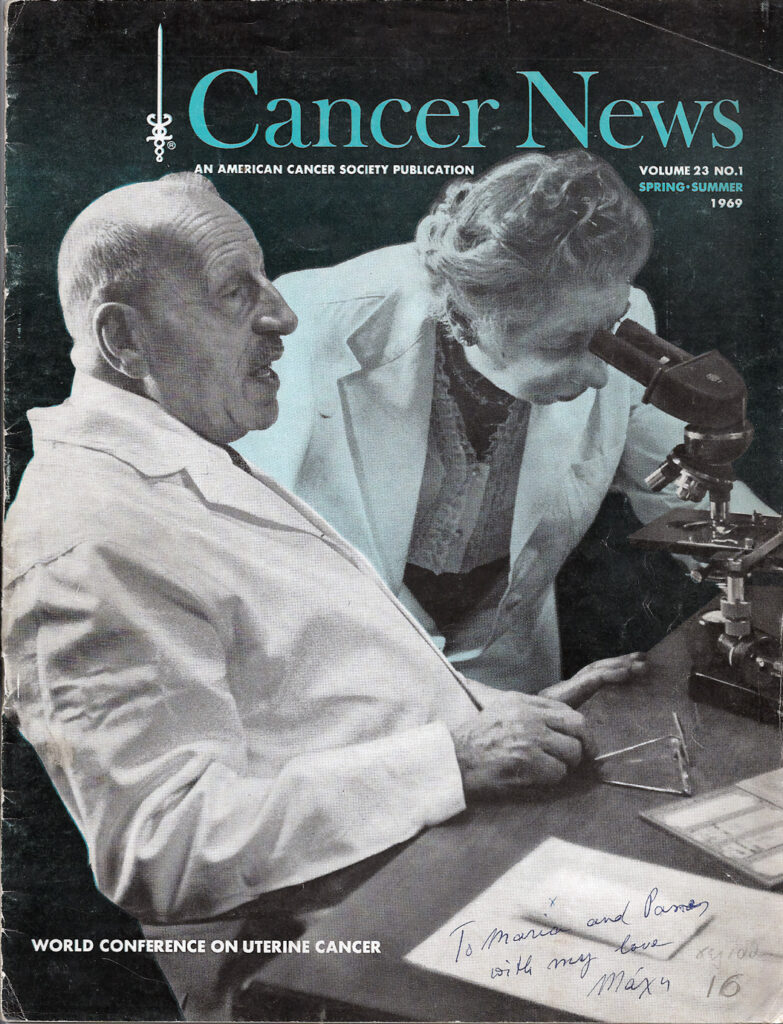

But in the decades to come, cervical cancer will be highly preventable. And what defangs this deadly disease starts with a test—the first widely used screening not only for cervical cancer but any cancer. It’s called the Pap smear for your husband, George Papanicolaou. But that acknowledgement should also nod to you, Mary Papanicolaou, who climbed on an exam table nearly every single day for 21 years to let George pluck cells from your cervix.

Mary first meets George when she is 16 and still known by her nickname, Mache. He is the brother of a friend, in his early 20s but already a doctor, having entered the University of Athens at age 15. Only George doesn’t want to be a doctor. He yearns to do research, carry “the flag of progress” into the future, as he once writes. He tells Mary as much when he runs into her a few years later. He soon proposes. If she marries him, she’ll have to forgo having children, he tells her. They would be much too distracting.

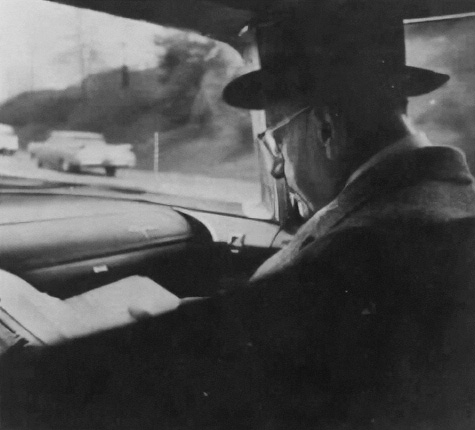

He is a demanding man, a perfectionist. George once talked a surgeon into breaking his legs, which were minimally bowed, and set them in casts to heal flawlessly straight. And like his father—a physician who also served as town mayor and member of the Greek parliament—he is consumed by work. Later, on his way to a professorship at Cornell, he spends 14 hours a day in the lab, rarely taking a day off or a vacation.

She is 19, to his 27, when they marry. She comes from a prominent family, too, a relative of the Greek heroine Aristarchos Mavroyenis, who spent her fortune to help the country win its independence from the Ottoman Empire. Mary is bubbly, well-educated, and short—standing barely five feet tall—but her given name is Andromache, “a woman fighting alongside men.” She becomes Mary in the United States because it’s easier to pronounce.

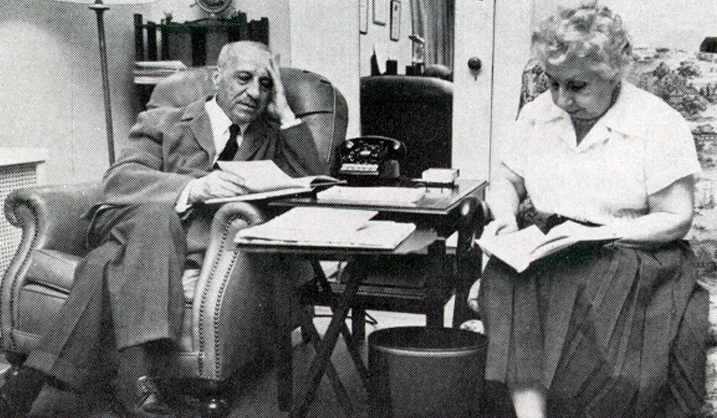

Little of her writing will survive. But though her reasons may be lost to history, Mary makes George’s mission her own. She assists in his lab—unpaid since Cornell refuses to give a salary to a spouse. For years, she drives George to work and back, an hour each way between their home in Queens, so that he can catch up on news or his notes in the passenger seat. She fills thermoses with his beloved cold orange juice, packs lunches, takes dictation as he works into the night. And every day she lets him collect cells from her cervix with a glass pipette shaped like a turkey baster.

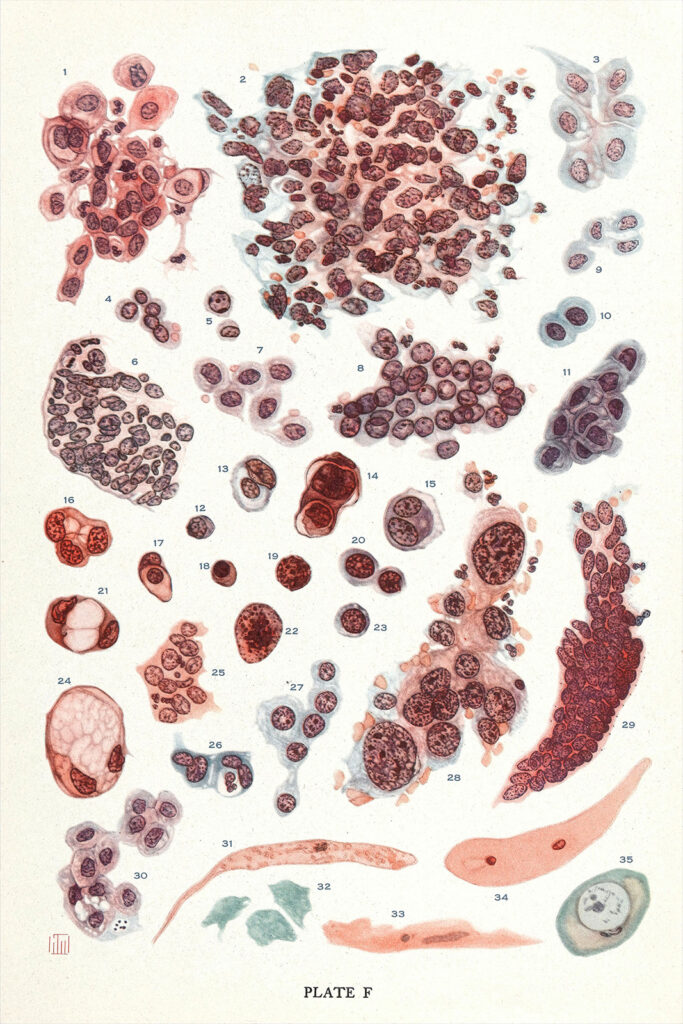

It’s the basis from which everything grows. By studying Mary’s cells, George learns how the tissue changes naturally through her childbearing years to menopause. What he learns will eventually be used to calibrate hormone treatments for women with menopausal symptoms or who are having trouble getting pregnant. He expands his study. In 1925 he starts examining patients and staff at Women’s Hospital in New York. When one develops cancer, George witnesses it under the microscope, her cells becoming enlarged and deformed. He declares it “one of the most thrilling experiences” of his career.

To new acquaintances, George sometimes introduces Mary as “my wife and victim.” In his scientific writing, he calls her his “special case.” Most women today will undergo perhaps a dozen or so Pap smears in their lifetime. Mary has 7,600, give or take.

It’s hard to tell how many Marys exist in medical history. Better known are scientists who experiment on themselves. Isaac Newton famously stuck a blunt sewing needle into his eye socket to see how it would distort his vision. Barry Marshall swallowed Helicobacter pylori to prove it causes ulcers. The neurologist Henry Head had a surgeon cut and repair the radial nerve in his arm to study nerve regeneration.

Less known are scientists who enlisted their loved ones. The most famous is Jonas Salk, who successfully inoculated his wife and children with his newly invented polio vaccine after first testing it in animals and children previously infected with the virus. A stranger example is psychologist Clarence Leuba who, to test whether laughter is innate or learned, tickled his infant son and daughter while wearing a cardboard mask to block any inadvertent smiles.

Though she fights with George about many things, by all accounts Mary participates in George’s experiments willingly. She and George often bicker. Once, fed up with his commentary during commutes, she hands him a “license for back-seat driving” issued by the “State of Nervousness, Bureau of Nuisance.” She pushes back against his demands—that she read Nietzsche or play the piano for him when she’s dead tired after a long day in the lab.

She’s also the one who nudges George forward when his faith flags during the many years it takes to garner attention for his discovery. A first attempt fails badly. In 1928 George accompanies his supervisor, a eugenicist, to the third Race Betterment Conference in Battle Creek, Michigan. There George describes his discovery of cervical cancer–signaling cell changes alongside presentations titled “Who Outbreeds Whom?” and “The Menace of the Melting Pot Myth.”

Few are impressed. It may be because of George’s blurry slides and misspelled words, as some have suggested. Or the assembled eugenicists may see this Greek immigrant as part of a problem.

It takes another decade for the medical community to take notice. George collaborates with a gynecologist named Herbert Traut to test the Pap smear on more than 3,000 women. They find 127 cases of cervical cancer, nearly all so early that they would have normally stayed undetected. Thanks in part to Traut’s influence and vivid illustrations by artist Hashime Murayama, their 1943 book, Diagnosis of Uterine Cancer by the Vaginal Smear, becomes a new cornerstone of medicine.

In 1960, the American Medical Association begins recommending women be screened with the Pap test. Over the next decades, cervical cancer deaths plummet by about 70% in the United States (although fatalities remain high in less developed countries where fewer women have access to screening programs.) The Pap smear becomes known as the most successful cancer screening test in history. Another researcher improves George’s method, replacing his glass pipette with a scraping scapula that collects more cells. And later research finds that the human papillomavirus (HPV) triggers most cervical cancers and can be prevented by a vaccine.

Mary frets as George is passed over for the Nobel Prize—five times, by some counts. (Some speculate the Nobel committee is hesitant to honor another cancer discovery after research makes it clear the committee blundered in giving the 1926 award to a doctor who claimed a type of roundworm can cause stomach cancer.)

But other honors materialize. When Mary is in her early 70s and George in his late 70s, both still working, she lets him uproot her again, this time to Miami, where an institute is being built for George. He dies of a heart attack shortly before it opens. Mary is lonely in Miami, but she stays to keep an eye on the new center.

Only when she dies herself in 1982, at age 92, does her path separate from George’s. Unlike her husband, whose body was brought back to New Jersey for burial, Mary has her ashes thrown into Biscayne Bay. Perhaps, some think, so the sea can carry her back to Greece.