Producer Mariel Carr talks to historian of science and former Science History Institute fellow, Luis Campos, about his article “Strains of Andromeda: The Cosmic Potential Hazards of Genetic Engineering.” He shares how Michael Crichton’s first novel and the subsequent film influenced the conversation and controversy around recombinant DNA research in the 1970s.

Credits

Host: Alexis Pedrick

Executive Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Samia Bouzid

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

Resource List

The Andromeda Strain. IMDb.

Campos, Luis A. “Strains of Andromeda: The Cosmic Potential Hazards of Genetic Engineering.”

Transcript

Alexis Pedrick: I’m Alexis Pedrick, and this is Distillations.

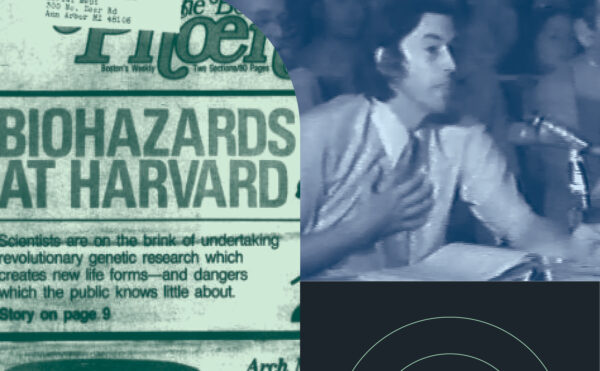

In this episode, our executive producer, Mariel Carr, talks with Luis Campos about the 1971 science fiction thriller, The Andromeda Strain. In his essay, “Strains of Andromeda: The Cosmic Potential Hazards of Genetic Engineering,” Campos writes about how the film seeped into the recombinant DNA debates of the 1970s and became a common reference point.

Mariel Carr: So, I want to talk about the timing of this film. The book comes out in 1969. The film comes out in 1971. Asilomar happens in 1975. How did The Andromeda Strain seep into these recombinant DNA discussions and debates? Was it fully in the zeitgeist?

Luis Campos: Yeah, I think The Andromeda Strain was quite a popular first novel to come out for Michael Crichton that sold, you know, 2 million copies when it was first released, which is, you know, a pretty good showing. And I think what it did is it changed the concern with the Cold War fears of nuclear catastrophe, or atomic weapons, into another realm of biohazard, and the idea that there might be other things that we need to be worried about that are not from the nuclear realm.

There is a large number of debates that were going on at the time in what we now call “planetary protection,” or the idea of contamination, either from the Earth to other places in the solar system, or from somewhere in space back to Earth. And that was really kind of a live scientific topic when this new field of exobiology was being created in the late 1950s and through the 1960s. And so, at the height of the Cold War space race and trying to show, you know, preeminence in science and technology by going off into outer space, the concern was, you know, will we find living forms there or will we inadvertently bring something back? And so I think that’s the context for Michael Crichton’s story is that people are already thinking in NASA, in other sorts of spaces of planetary biology: How would we look for life? What would it be? How similar is it to earthly life? Would it be dangerous for earthly life?

And so when Michael Crichton was in medical school, he had heard an idea that the paleontologist G.G.Simpson had promoted in a book called The Major Features of Evolution that was published in 1953. And it was an idea that there might be organisms that live in the upper atmosphere. And so Crichton basically took that idea, combined it with this exobiological context of the time, and then invented the story that became so popular that we know so well.

So The Andromeda Strain is both a shift from nuclear fear to biological concern, and also a story that is very much a story of the space age and its time. What’s so interesting is how, then, that space age story becomes woven into the recombinant DNA debates that would come along a few years later. So it became a ready reference point for people who wanted to think about: What are the potential dangers of newly engineered life forms that we might make?

And there’s an interesting, intertwined history between people who are thinking about how nature may have come up with other forms of life in other worlds, and how we might engineer other kinds of life down here on Earth. In the one case, that sounds like “discovery” if nature did it and we can figure out how. And the other case, it sounds like “engineering.” And so one is science, and the other is engineering. But some of the same people were involved in both of those questions: What life might look like elsewhere? [And] how we might control it here.

Mariel Carr: In your article, you mentioned how The Andromeda Strain was the first movie to show a mass American audience someone wearing a hazmat suit to deal with biological contamination. And I found that so interesting.

Luis Campos: So there’s a number of scholars who’ve thought quite deeply about Michael Crichton’s kind of legacy for the history of science, and Joanna Radin is among them. And so the idea that there are new things the American public has to encounter and think about, and sometimes they realize that through fiction rather than from news reports, the hazmat suit became one of the symbols of this new field, that kind of cemented the idea of fear and concern about the engineering of biology, which is quite different than the early 20th century, when people were quite excited about the idea that you could create new crops, new flowers, new fruits to enjoy, the possibilities of new kinds of biotopias, as Jim Endersby has called them.

But I think by mid-century, with fears of environmental contamination, with an increasingly radioactive world from atomic testing, and with this idea about potential hazards coming from germs from space, I think all of that came together and kind of cemented a new public understanding that there was something to be fearful of here, rather than something to explore and to enjoy. So that reflects the time, I think, as much as anything else.

Mariel Carr: Your essay is titled “Strains of Andromeda.” Tell me what that means, why you flipped that term.

Luis Campos: So we are familiar with the title “The Andromeda Strain,” but what I was interested in following is how many different sorts of people invoked the book or the film in their discussions about what recombinant DNA meant and how they wanted to think through what potential hazards or risks it might present. And so there are many different ways that it gets narrated or invoked or has an afterlife. And I wanted to kind of highlight those contestations over what does it mean to think through a work of fiction about what the next kind of step or advance in science might be. And so I thought, let me refer to those as “strains of Andromeda” then—different ways that people are applying or using this story.

There’s also a way that evokes kind of the earlier context of using Andromeda as an obvious sort of place to talk about the next galaxy out there. But there’s earlier references from the 1930s and 1940s thinking about how there might be life in this other galaxy, how it might radio something to us that would give us instructions on how to create their life form here. That’s an idea that comes in earlier versions of science fiction.

So Andromeda has long been kind of invoked already, long before The Andromeda Strain book came out, as an easy reference point for the next neighbor in the universe that might have some form of interaction with us. And so various astronomers and science fiction authors have used Andromeda in that way. So in that sense that we have two different senses of strain there, right? We have a biological idea of a strain, but we also have the sound or the hearing of something from a great distance that’s coming to us. And both of those things I thought were a nice way to riff on that.

Mariel Carr: I’m envisioning it kind of like tentacles, and you do this very thorough job of explaining all the places that, you know, The Andromeda Strain was, was mentioned like it reached Congress and NASA. Could you just walk us through what some of those were?

Luis Campos: Yeah. So it came up in NASA, eventually came up in Congress. It was present in discussions among scientists in the early days of what we now think of as genetic engineering, as something to expand their sense of what potential futures might be, that the fiction was a way that they were thinking through scenarios of what might be likely to happen, or how something might play out.

The journalists, of course, picked up on this and began to report on it, but that stage had already been set for decades already of thinking about Andromeda as a reference point. So the fact that so many different constituencies or agents that are involved in this story kind of all circled around the same point of reference, and then they began to read very different meanings into it, I thought was something that was that was quite striking, that even at the highest levels of Congress or the Secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Human Welfare begins to say, you know, the reason why we’re here is because of The Andromeda Strain, even at the same time that other folks are saying this is just, you know, ridiculous sensationalism by journalists who are trying to sell a copy of a newspaper.

So, it gets invoked and used by lots of different people in their arguments with each other about what is the safest way to advance an interesting and new scientific technology.

Mariel Carr: And did The Andromeda Strain influence journalists who were reporting on Asilomar in 1975?

Luis Campos: I think so. So I think for already for a few decades, Andromeda had been a reference point for people. And so, when the book comes out at the height of everybody wanting to talk about space all the time, right? To think about the year in which this is being written and landing on the moon; to have astronauts being paraded on TV, coming home, and they’re in a quarantined facility as they’re being greeted by the president. The idea that there might be something dangerous about them returning to Earth, and who knows what space germs they’ve been exposed to, this is something that’s already in the news.

Something that people are already seeing and thinking about—these exobiological questions at the time, about germs from space or planetary protection and how to make sure of this despite the fact, of course, that we’ve left many pounds of poop on the moon. So if there is any pristine environment on the moon, it has already been deeply affected by those things that we did not bring back with us when the craft returned to Earth.

So, I think it was an obvious and ready reference point to think about these sorts of issues. And when the scientists themselves began to say, just like we had to develop these technologies to figure out quarantine procedures for astronauts returning to Earth, there is something that we can learn from that for thinking about how to create safe laboratory designs. And the idea of [a] kind of space quarantine turning into laboratory safety is something that many of the scientists themselves were thinking about. And that is going on side by side with the larger American public beginning and fascinated by and reading and watching The Andromeda Strain. And it’s when those two different narratives come into conflict that the drama begins.

Mariel Carr: Can you give me any specific examples about how journalists talked about this, either at Asilomar or at the Cambridge City Council hearings the next year?

Luis Campos: Yeah. So even before the Asilomar meeting in 1974, when a lot of attention is being drawn to these prospects for genetic engineering, there were editorials that were written, like in Bioscience. There is an all caps headline that said “Andromeda Strain.” And the way that they wrote about it in the editorial was: “It’s happened. Specifically, molecular geneticists have discovered relatively simple methods for the introduction of specific genes from vertebrates and other organisms into the genomes of bacteria, such as the common E.coli of the human gut. Further, alien genes from other species of bacteria, and even viral DNA can now be grafted into a bacterium where it was not previously present. Appalling dangers to the human race are inherent in this discovery.”

So, it’s interesting to hear in something that’s written in bioscience as an editorial in the year before Asilomar, the reference is that this new technology is, in fact, an Andromeda strain, right? Or a question mark following it. So even within the realm of scientific discussion, the drawing on that as the reference point was part of the way that the issue was being talked about, kind of at the same time that the Berg letter is published. When Paul Berg publishes a letter, along with other signatories, 11 other folks, saying that there are two classes of experiments that maybe shouldn’t happen until we have figured out the right kinds of facilities or the right ways to do it safely. And that letter is essentially what called for the Asilomar meeting then to take place about six months later in the late winter of 1975.

So I think The Andromeda Strain is not something that journalists are inventing after Asilomar to describe what happened, although many of them do, there’s many different pieces that cover it in exactly that way, but even before the meeting happened, it was a reference point to try and think about how to bring together these questions of space with the questions of what we might be doing in our laboratory.

Mariel Carr: I have to tell you that when I read that line; I underlined the word alien twice.

Luis Campos: Exactly. Yeah. The use of the word alien. Is this by chance? Is that just a choice of something? So what I think is so fascinating is the language of breaching species barriers is kind of everywhere at this time. There’s an idea that species are somehow fixed and stable things, despite all the ways that we know that they can change and evolve over a long period of time, but that this was a rapid way of moving bits of heredity around from one to the other that had never happened before, and therefore we didn’t know what the consequences would be of that.

And so that idea of kind of massive changes that could happen just so quickly as a result of our own intervention felt like, it seems to people, this concern about aliens from elsewhere. And of course the idea of alien biology from elsewhere having an impact on the world is an idea we can trace right back to H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, the Andromeda kinds of arguments from the 1930s and 40s. It’s not a new idea at the time, but I think it’s drawing on this idea of what is natural, what is not natural, what is terrestrial, what is extraterrestrial? And it’s weaving those different stories together.

That’s what I thought was so interesting in this. It’s not simply a story of someone writes a really fascinating science fiction account that becomes very popular, and then it becomes the ready reference point. It’s that these two areas have already been intertwined for several decades of thinking about what a pandemic might be, or an epidemic, or a biological weapon, or something that has to do with the impact of a space form of life arriving here on Earth.

And so that to my mind, that evocation of an alien gene is not an innocent word choice. It’s, in fact, deeply informed by these decades of people thinking about one topic, using the ways of thinking from the other topic.

Mariel Carr: So the film takes place in this top secret, ultra secure facility out in the desert called Wildfire. And, you know, like it’s underground. No one knows where it is. Do we actually have facilities like this? Or did we when this film came out?

Luis Campos: So we have a place called Fort Detrick, that was one of our top protected places for doing hazardous biological work on really problematic pathogens for a variety of different reasons. And those facilities were designed with the idea of keeping whatever these bugs were, these most infectious things, inside. So we definitely had various programs concerned with understanding how infectious organisms work and how we need to keep them confined to certain places. That goes back to, you know, island environments where we have laboratories for other kinds of communicable diseases and livestock. We want to make sure that doesn’t spread through agriculture. So we’ve long had these sorts of mechanisms at the federal level to try and have safe places to do potentially hazardous work that we just don’t want to have happen anywhere. So, those laboratories existed.

There is an overlap there with the potential concern for the weaponization of biological agents. That’s a major story through the Cold War of Soviet programs for bioweapons—other countries having efforts at bioweapons research, and what is the line of what kind of research is trying to understand an organism, and what eventually leads to other sorts of ways to weaponize it? So those facilities existed at the time, and I think that overlap between quarantining people coming from space and the already extant microbiological knowledge that we had, were things that were drawn on when thinking about: How do we create a safe laboratory environment for the kinds of recombinant DNA work that people wanted to do by the time that became possible in the early 1970s?

Mariel Carr: How did scientists react to these comparisons?

Luis Campos: Yeah, that’s a really interesting question. The way I began to write this piece was that I had noticed that there were so many references to The Andromeda Strain—in the correspondence, in the minutes of the meetings, in the various documents that existed—that clearly something was going on. That this was a common reference for everyone. And then kind of piecing together, well, who was using it in what way and how did they begin to reason with it? How did reasoning with a work of science fiction end up being part of the work of science—was a question that became really interesting to me—and then got denounced for being sensationalism afterwards. How can the same text, the same story, be used in such different ways before and after, and how did that play out?

And so it was really an effort to put all these different examples of The Andromeda Strain together and see what is the way that it seems to play out? You know, for Paul Berg, who had organized the Asilomar meeting and who had written that letter in the summer of 1974, he was quite annoyed by this kind of wording and a couple of different places. He says this, you know, “I thought, in fact, many of the reporters had missed the point. I thought they were playing up the theme that we were trying to head off the prospects of some misuse of genetics, and it could create all kinds of monsters and Andromeda strains, and that we were warning the world that this line of research should not be done. And there were very few who seemed to perceive that what we were talking about was that this was an important line of research. We were in favor of doing this research.” So the idea that the research was important and interesting, but needed to be done safely and therefore should not be done until it could be done safely, is what Berg thought he was doing, and he got upset, then when it was narrated that there is an Andromeda Strain that’s going to result from this and that this is why it shouldn’t be done when that wasn’t what his intention was at all.

At another moment he says, “Andromeda Strain? I remember reading that book and seeing the movie, but I haven’t thought of any situation where one could create something that would have that similarity. We’re talking about methodology that effectively moves genes around but doesn’t create a new gene.” And he says a couple other things there. And he’s like, “I’ve offhand guessed that a lot of the regulatory mechanisms that hold and check most of the biological world quite effectively would still act even in these recombinant structures, so that an Andromeda strain,” he says, “taking your question literally, an Andromeda Strain is unlikely. Something that can do something new, like chew up plastic and therefore not be containable and grow on the plastic or whatever the Andromeda Strain grew on.”

Luis Campos: So he’s in that passage acknowledging he’s read the book and seen the movie, right? And he’s struggling to figure out, you know, how is what I’m doing different than that? How do I make sure that what I say can’t be equated with what’s there? And he’s not entirely clear, but the idea that the biological world might, you know, act and hold it, you know in control is, in fact, one of the ways that The Andromeda Strain story ends. So even as he’s fighting against the narrative of the story, he’s also invoking how the movie ends to explain a biological phenomenon that he thinks will be active in the case of it.

Norton Zinder, another organizer of the meeting, also said that something had changed in the aftermath of the meeting and he said that, “there’s a class of newspapers in the country epitomized by the National Enquirer, which thrives on sensationalism, and that recombinant DNA chimeras are made to order for them. The monsters formed and the horrors caused were only limited by the imagination of the writers.” And so, Norton Zinder was quite upset that you know, talking about the potential hazards of this seriously in a scientific way was being narrated by journalists afterwards in a way that any possible dangerous future they could envision would be something that they could write about.

Luis Campos: There’s also someone at NIH and we don’t know who, but we have minutes of this meeting who had said that, “the people who talk about The Andromeda Strain have media access, and they have something to say to the media that you can’t say. I mean, it really is molecular politics. It’s got nothing to do with science, nothing to do with rationality. I’m reasonably safe on those grounds,” this person said. “It’s molecular politics, not molecular biology. And I think we have to consider both because a lot of science is at stake.” So inside the NIH, you hear people thinking about what is the difference here?

And the difference is The Andromeda Strain is how the media talks about it. And then we’re not actually engaged in the issues of molecular biology, then it just becomes molecular politics, and cultural understandings become part of how these issues get talked about. And the fact that gets acknowledged inside the meetings where they’re trying to figure out how to produce guidelines for work with recombinant DNA shows the cultural impact of the choice to narrate this new technology using that kind of language.

There are other choices, other ways that journalists could have described this new technology, Frankenstein being one example, Jaws being another example, to think of other popular movies of the time. Or even there’s references to Farrah Fawcett-Majors being a reference point that journalists were trying to explain things about recombinant DNA.

Luis Campos: There are some references that have escaped our familiarity now, later in time, of why this would have [been] seen as logical. Whereas The Andromeda Strain was something that kind of carried out for such a long time. So, I think the idea that there’s many different scientists who are fully aware that these are the invocations that are being made by the journalists afterwards is an important part of the story.

But just as important is, even before the Asilomar meeting happens, there are ways in which they’re drawing on the same tropes themselves to think about what might happen. When they’re trying to envision what future world they might be bringing into existence, fiction is one of the ways that they’re doing it. When they can no longer control the narrative and how journalists write about it, how the public might respond, or the idea that the disaster scenario has become more and more fantastical, then it becomes that any reference to The Andromeda Strain is a problem, and that we shouldn’t be using that. We should be doing science that doesn’t refer to it. And so that kind of changing moment between science and science fiction—when does science fiction count as part of science? When is it part of the irresponsible popularization of science? I think that’s an interesting thing that The Andromeda Strain helps to highlight.

Mariel Carr: Yeah. It’s interesting. And I’m thinking back to that Paul Berg quote and how his defense gets very literal. Like he says, you know, recombinant DNA is not going to, you know, eat plastic. It’s not going to have the same properties as the Andromeda Strain, where it sort of seems clear to me that the parallels are not that specific, that it’s more just overall anxieties of these new uncontrollable things. And, I guess to me; it seems not surprising that people would have all sorts of anxieties and fears about anything that was unknown and brand new. And it seems like there was a certain amount of surprise on the part of scientists. And maybe just a sort of growing impatience—that they grew tired of it.

Luis Campos: I think we often think that other people think the way that we do, whatever it is that our world is. And when we then break out of that world and encounter people who have other interests, other vocabularies, other things that matter to them, other ways that they come to understand the world or what their responsibilities are in it, that can be what we might call an interesting learning moment.

And so the idea that you could, in your own in-group, talk about what might happen and then describe your concern in what you think is an ethically motivated way to blow the whistle, as it were, and to say, please, let’s not do these kinds of things until we can talk about what might happen. This is the Berg letter. This is what the Asilomar moment is. They thought that it was clear and easy. If we think very scientifically and rationally about this and say what we understand to be the case and take the right actions to it, that other people will interpret our actions in the same way that we do. And of course, that’s not how the world actually works. People see things by their own lights.

And so I think that’s one example where they had imagined that there might be the kind of outcome that would be “of course they’ve thought this through. There are good steps. There’s the next thing that should happen.” And when it took a path that’s quite different from that in the months after Asilomar, that became deeply concerning; it became a new way of grappling with, what is the relationship between science and society? What is the role of these scientific communicators, of these journalists, of these people who are bringing word and news about this to a larger public? And of course, for those communicators, it matters that the people you’re trying to reach understand what it is that you’re saying.

Luis Campos: And what are the reference points that the person on the street has to this sort of issue that’s going on? It made perfect sense that they would refer to The Andromeda Strain, but it also made perfect sense that the scientists would find that bothersome, and they’d find it problematic. And when The Andromeda Strain becomes the one reference that is repeated over and over again at every level, as these guidelines are going through a governmental process, as, you know, various cities are deciding what regulations they want to put in place and where research can happen and under what conditions, it’s not simply a matter of how to describe a new technology. It actually becomes quite relevant in real-world decision-making that’s going on. And you can’t quite control what people think that metaphor or that story of The Andromeda Strain is doing.

And so I think that’s the moment where the realization that perhaps making these references was not helpful became part of a larger political battle that scientists found themselves unexpectedly in. They thought they were doing the right thing by raising concern and proceeding responsibly. And their intentions and their efforts were understood by non-scientists, sometimes in quite different ways.

Mariel Carr: So you write about how there was this pushback that the public was leaning too heavily on science fiction, that people were sort of confusing fact and fiction. And I thought that was interesting because to the lay, non-scientific public, something like recombinant DNA is just as foreign and sort of on the same plane as science fiction as something that they see in a movie like The Andromeda Strain. So I guess in some ways, recombinant DNA was science fiction to them; it’s brand new. They don’t really know about it. It’s science fiction come true. How did that dynamic come into play?

Luis Campos: Yeah. So, I think how to talk about an issue with the public when the public has not yet been made aware of the issue is an interesting question that scientists found themselves faced with. And the Berg letter and the Asilomar conference is one part of it. I think activists who are concerned about these issues, like the group Science for the People, that wrote an open letter to the Asilomar meeting, were also grappling with that issue. And in fact, the reason why they wrote that letter to the meeting was because they knew that there wasn’t a public interest in this topic of moving genes around. It was not something that was being widely talked about. And what they had usually done was discussion and organization with publics about issues that mattered to them.

And so, on a topic that didn’t matter to the public, what were they supposed to do? They said, we don’t usually go to the elites and to confront them and to ask permission for how we want to kind of make our analyses and critique what’s going on and how science is being used. But in this case, we had to because there wasn’t actually a public domain for that. So I think in this case, The Andromeda Strain made it possible for a larger public to have some sense of what it was that might be at stake, why one should care about the nature of laboratory design, or what sorts of creatures might be worked on, or what sort of work might move bits of heredity from one to another with the potential hazards that that might involve if you’re working on certain kinds of viruses or microorganisms.

So at that very kind of abstract level, the idea that there’s a potential hazard, something bad might happen—you’ve all read the book or seen the movie, right? That’s an obvious way to make the connection. And yet, the idea that a work of fiction was a way for the public to understand the works of science was something that made many scientists quite uncomfortable. And especially when various scientists themselves began to use that sort of frame of hazard and danger, rather than safety and care, to write pieces that got published in The New York Times magazine and in other places. You know, “Strains of Life Strains of Death” was the name of one of them. To use that word, strain is, again, not an innocent choice. Right? If you’re a scientist who’s, you know, writing a piece in The New York Times, you talk about strains of life and strains of death in ways that create a great deal of public concern. You don’t have to say the word Andromeda strain for The Andromeda Strain to be invoked.

And so I think many scientists saw these sorts of moves happening in the sphere of science journalism or public communication that meant that The Andromeda Strain was no longer a helpful tool for thinking through possible scenarios, and what we might have to worry about. It became something that itself was the problem, and that the real issue here was, you know, what was going—to use the word wildfire—what was going wildfire here was not the strains themselves, it was the talk of The Andromeda Strain that then began to dominate and became the only way that larger publics and politicians and the secretary of an important department would be able to think about this. So in that sense, the development of the sensationalism is an outcome of different ways that the story gets used.

Mariel Carr: So I think that personally, I feel like if there’s one thing this film does really well, it’s conveying, you know, what a futuristic top-security biological lab looks like. And there’s all these precautions that they’re taking in them. I’m actually going to play a clip.

The Andromeda Strain, 1971: You are about to undergo longwave radiation. A buzzer will sound. Close your eyes and stand still. Or blindness may result.

Mariel Carr: So we see them stripped down, naked. They’re exposed to longwave radiation. They walk through some sort of disinfecting sludge. My favorite part is when, at one point, the very top layer of their skin is burned off. They put on this sort of medieval knight helmet to protect their faces.

The Andromeda Strain, 1971: We face quite a problem. How to disinfect the human body? One of the dirtiest things in the known universe.

The Andromeda Strain, 1971: That is without killing the human being at the same time.

The Andromeda Strain, 1971: It gets tougher as we go, I’m afraid.

Mariel Carr: And of course, when I’m watching this, I’m thinking of actual biosafety levels P1 through P4 and what the design of them looked like. And you mentioned you have this line this term in your essay, “Andromeda Strain Design Syndrome,” and I wondered if you could talk about that.

Luis Campos: Yeah. I have a footnote to this. The Andromeda Strain Design Syndrome was defined as, quote, “the inclination to overcomplicate the design problem when building biomedical research facilities.” And so that idea that we want to be better safe than sorry, and let’s make our laboratory design as complex as it could possibly be to make sure that nobody can accuse us of being improperly prepared for dealing with dangerous organisms became part of universities and their legal teams wanting to make sure that they would not fall subject to those sorts of criticisms.

And so there’s even an internal memo that emerged from the Office of Technology Licensing at Stanford in 1976 that was called “The Technology and the Threat.” And so, in their case, they wanted to use licensing as a way to inhibit scientists, they said, “from conducting research that might result in an Andromeda strain being unleashed upon the world, and that the fact that the university may be perceived to be profiting may cause the university to be tarred with the same brush as the researcher that develops the Andromeda Strain.” So I struck there that even the legal advice people are referring to the public implications of the Andromeda Strain being invoked as a damaging aspect to their. reputation.

So in a sense, the Andromeda Strain Design Syndrome is: when you’re trying to design a new technology, a laboratory with different levels of safety, how much safety is enough? And who authorizes that? And isn’t there always a possibility that somebody else can say, well, you should do this other thing, in addition, one more thing on top of it? And so that there’s a way in which the concern that some quarters had about what sorts of work should be done where, led to an arms race of laboratory buildup that was an over complication and an over design that one didn’t need to do that.

I just spoke with an original participant at the 1975 meeting the other day, and she told me that she was quite perplexed by some of these regulations that had come into place after the Asilomar meeting, and until they were relaxed about two years later, and that she wanted to do work on various chicken virus sorts of things, and there was all these procedures she had to go through in order to enter her laboratory, and how she could do this work, which she thought was pretty funny given that no one has eggs in the refrigerator at home all the time, and you know, they’re full of DNA, and there’s all sorts of other things that eggs might have with them.

And so the ways in which the care and the concern (rightfully generated) to think about what might happen and what has what probability or chance of happening is reasonable and what can we do to address it. All reasonable things could lead to a situation where laboratories were then over-designed and addressing fictional problems themselves. That the fiction itself could create a fictional problem that didn’t need to be addressed.

Mariel Carr: I’m going to play you a clip of the climax of the film, where Andromeda is basically eating through the structures of Wildfire that are supposed to keep everyone safe.

The Andromeda Strain, 1971: The gaskets are decomposing.

The Andromeda Strain, 1971: It’s Andromeda.

Mariel Carr: So my question is, what does this say to you? What did it say to others amidst this whole controversy? That in this film, in this story, a system as elaborate as this fictional lab, where people are walking through sludge. They’re burning off the top layer of their skin… What did that say to people? That the best of the best still might not be enough to contain something that’s brand new, that has properties that are so foreign that we don’t even know how to contain them. Did it feed into the debate? Did it add to it at all?

Luis Campos: I think part of what you’re asking is—well, another way to frame it: there was a great deal of trust in science in the early 20th century. There is a story that we often tell about the middle part of the 20th century—the atomic bomb is a useful place to point to—the idea that science might make the world better is perhaps challenged by the arms race, challenged by the use of new kinds of weapons of war that science made possible for all the right reasons according to the narratives that were offered in 1945, right? To make the world free for democracies.

And yet, the kind of dawning awareness through the environmental movement, through the antiwar movement, through many things in the 1960s and 1970s is that science is not simply only something that betters the world, but is something that has been connected to other things that people care about, to pollution, to harm. Questions of expertise and of authority are also emerging. At this time, we have student movements. We have antiwar movements. We have, of course, Watergate and the crisis of trust in institutions, right? And the idea that even at the highest level, our institutions may not be doing what they were envisioned to do by the founders. These sorts of things are all questioning the place of science, and who knows what? And can we really trust our institutions to work the way that they should?

We were promised all sorts of wonderful things, and we’ve had many complex things that our world has emerged in.

Luis Campos: Science has produced incredible, wonderful benefits. But it was also associated with many people, with some of the things they were most worried about in the 1960s and 1970s. And so, rather than assuming that the laboratory would be okay, it seemed responsible; it seemed ethical to question, how do we know? What might happen if? Do we want to do this kind of research if it would escape and cause these sorts of harms?

We have a greater awareness about human subjects research. The idea that people should not be exposed to harms unless they have freely and openly consented, after having been informed of what the risks might be, of engaging in some kind of scientific research. That’s also a big change that’s happening from earlier on until this moment, where all sorts of scandals are coming to light about people who’ve been exposed to things without their knowledge, without their consent.

So the idea that someone might be interested in following some technically sweet question, whether it’s the development of the atomic bomb or some kind of biological system they want to know about, and that there is freedom of research to be able to explore these, these sorts of questions and that that’s what makes science in the US in particular, so strong was the narrative at the time is challenged by these other questions of just because you want to do something doesn’t mean that you have an unlimited right to do so. That if you cause harm, you are responsible for that harm, that you might not be the best person in a position to decide whether your research should go forward or not.

Luis Campos: And so the very move that, for instance, Paul Berg made in that Berg letter to say we want to be careful and think about this and we want to have a meeting to talk about it—in very short order, then that meeting starts to get narrated as kind of the opposite of what many of the scientists involved thought they were doing: that they were being upright, forthright, they were being honest. They were sharing what their concerns were. They were the only ones in that position to be able to raise those issues and those concerns at a time when the public wasn’t aware of those issues, and they felt it was the right thing to do and to call for a moratorium or a voluntary deferral, as they first referred to it in order to make sure that those dangerous futures wouldn’t happen.

So, the concern that the experts might be conflicted, that they might not know how to calculate the risks, that they might gather at Asilomar and leave without having produced any sort of declaration or statement, would be asking for the government to regulate them instead.

Luis Campos: And so that became one of the concerns that emerged out of the meeting, and that the lawyers at the meeting, the legal experts also said, you know, we have a system of law in this country. If you cause harm, there is a way to address that. It’s not simply a question of what research you’re interested in doing. It’s a question of your role and your place in the larger society. And you may not be the ones best informed to decide what kind of research should happen.

So all of those kind of transformations that are happening right around the time of the Asilomar meeting, I think are connected with the idea of: are scientists the ones to best decide what sort of research should be done? Who is the person to assess risk of different sorts of things at a technical level, but then at a social level? Where do we want our monies to be invested? Why are these questions and these scientific problems of interest rather than these other ones that might be useful? All of that kind of overturning of an early 20th-century consensus about the relationship of science and society, I think, was in play at that time. And so to think about what if the scientists are wrong? What if they don’t know enough? What if nature is unpredictable? What if these experiments we have in mind have never happened before in evolution? What might the consequences of that be?

For many people, those were reasonable concerns to raise. They were, in fact, reasonable for some of the scientists at first. What’s so interesting is that The Andromeda Strain then connects with this post-Asilomar moment, and then it becomes a justification for restriction of regulation, for Andromeda Design Syndrome, to make the laboratory as complicated as possible. And so the dynamic starts to play out then, that there are different groups arguing what they think the future of decision-making about this should look like and how it should be done.

And the deep irony, of course, is that the very thing that was held to be the right model of openness and using your technical knowledge for public good, lead to a meeting that then gets denounced for being elitist, closed door decision making by technocrats in their own interest.

The Andromeda Strain then enables that concern and that idea that, is this just germs from space? Is it another planet trying to contact us, sending things here? Is it a military experiment gone awry? Right, these are different ways that The Andromeda Strain story plays out in the book, and in the film, that are activating different concerns and fears of the public that have everything to do with the transformations that we think of as the 60s and 70s.

Mariel Carr: When did people stop talking about The Andromeda Strain and why?

Luis Campos: That’s a good question. I don’t think there’s some big, clear, dramatic moment where it gets replaced. One narrative that we often tell is that there’s a pretty big shift that happens from the kind of Berg letter and Asilomar moment of the mid-70s to the Supreme Court decision that allowed the patenting of life in 1980. Diamond versus Chakrabarty. And so that made it possible to have intellectual property exist in these microorganisms that enabled many people feel the emergence of industrial biotech.

And so the story of the 1980s, in very quick order, becomes the capacity to industrialize these techniques and to produce things of use, right, to produce insulin, human growth hormone, other sorts of products that might emerge. And so the narrative there, I think, is that if the 70s was consciousness raising, ethical concern, wanting to do the right thing, calling for the meeting, engaging larger publics, having science be responsive to societal interest, understanding how science, communication and politics play into that dynamic—the story of the 1980s is promise, money, profit, and the idea of concern or fear of these organisms is replaced by their potential. And the idea that we’ve done many experiments and we’ve never produced a pandemic, we’ve never had the accidents that have happened in that way, that becomes the common narrative by the late 1970s.

That’s why the guidelines get relaxed within a couple of years. So, I think The Andromeda Strain resonated at the moment of fear and concern and the unknown, and didn’t resonate by the time you got to the 1980s, where the story needed to be something else. It needed to be about a company making money. And of course, in due time, Crichton wrote that story as well.

Alexis Pedrick: Distillations podcast is produced by the Science History Institute and recorded in the Lori J. Landau Digital Production Studios.

Our executive producer is Mariel Carr. Our producer is Rigoberto Hernandez. Our associate producer is Sarah Kaplan, and our sound designer is Samia Bouzid. This episode was produced by Mariel Carr.

Support for Distillations has been provided by the Middleton Foundation and the Wyncote Foundation. You can find all of our podcasts, as well as our videos and articles, on our website at sciencehistory.org. And you can follow us on social media at @scihistoryorg for more news about our podcast and everything else going on in our free museum and library.

For Distillations, I’m Alexis Pedrick. Thanks for listening.