For almost as long as there have been television networks, science shows have been part of the TV landscape. But science programming didn’t begin by accident. At first, it was a way for TV stations to build trust with their audiences; then, it was used as a ploy to get families to buy more television sets. But as the world changed, so did science on TV. Distillations interviewed Ingrid Ockert, a fellow at the Science History Institute and a historian of science and media, about five key contributors to the science television landscape: the Johns Hopkins Science Review, Watch Mr. Wizard, NOVA, 3-2-1 Contact, and our favorite turtleneck-wearing celebrity scientist, Carl Sagan. Our conversation revealed that successful science shows have always had one thing in common: they don’t treat their audiences like dummies.

Transcript

Science on TV: An Interview with Ingrid Ockert

Alexis: Hello and welcome to Distillations, a podcast powered by the Science History Institute. I’m one of your hosts, Alexis Pedrick. And today we’re doing something a little bit different. We’re talking to Ingrid Ockert, a historian of science and media and a fellow here at the Science History Institute.

I’m excited because the topic we’re about to cover is pretty near and dear to my heart. When I’m not hosting Distillations, I’m the manager of public programs here at the Science History Institute. My whole job is figuring out how to talk to the public about science. And that’s what Ingrid and I are going to get into today.

Why did TV stations start doing science programming? What was behind this growing interest in the public presentation of science? And probably most important to me, why does it matter? We’ll hear about how Ingrid first got interested in this topic. She’ll tell me about being a child, going to science lectures with her mother. Then she’ll walk us through the earliest science shows from the dawn of television, The Johns Hopkins Science Review and Watch Mr. Wizard.

She’ll tell us how Nova came along in the 1970s and changed the landscape of science on TV. And then she’ll tell us about a team of idealistic people who wanted to change the world through children’s television and how they brought us Sesame Street and 3-2-1 Contact. And finally, she’ll tell us about that iconic scientist-slash-celebrity Carl Sagan. And through it all we’ll learn about how science is presented to the public and what that means about who gets to be a science communicator.

Alexis: All right. So Ingrid, to start us off, tell us about why you’re interested in this subject. What got you thinking about science on TV?

Ingrid: I think I’ve always been very interested in the public presentation of science. One of my earlier memories is, you know, being a kid. Remember how in the 1990s everyone was obsessed by cloning? Like that was a big thing, like Dolly the sheep was a big thing, right?

Alexis: Yes.

Ingrid: I remember very vividly going to a lecture with my mother, and we would go to science lectures when we were little because my mom was working on finishing her bachelor’s. And she would take us, and we would be allowed to sit in the back of these lectures, but we couldn’t say anything. We just had to be quiet.

But I remember there was this one lecture about cloning. And I was, my mother said, “You can ask a question,” and I was like, “Oh, this is gonna be great.” And so I was like, you know nine, right?

Alexis: That’s a big deal.

Ingrid: Yeah. It was a good deal. Right? And so I remember the very end. I was really nervous, but I got to ask the professor a question, and like I don’t even remember what it was but the thrill of being like, “Oh my God, I’m talking to a scientist about something.” And I think in some ways it’s that excitement that carried through into this project basically. It’s this interest in sort of what about the spaces that we create where people can, who know nothing about science at all, like, you know, little nine-year-old Ingrid can go and talk to a scientist and be like “Gee whiz, Mr. Scientist. What’s up?”

Alexis: That’s amazing, I love it. Okay before we talked, I guess I kind of took science and TV for granted. I mean now there are shows about everything: baking, home renovation, singing, etc., etc. But science TV started somewhere, so who started it and, well, why?

Ingrid: So in the 1940s and the 1950s before public broadcasting exists, the people who are putting on these programs are on our commercial broadcasters, right? And they’re driven by their own interests, like, namely, to make money, right? And then to increase the public trust in what they’re doing. And so for instance you have a program that would run on NBC called Mr. Wizard. And it was put on by NBC to show their viewers that they could be a trustworthy station, which was especially important after the quiz scandals of the late 1950s, where it turned out that there were some people who had sort of played the odds and illegally chosen who’s going to win and lose in certain, you know, episodes of this one TV show.

Archival: In the Senate hearing room, the dramatic climax of the probe of fixed and rigged quiz shows. Charles Van Doren’s wife and father, poet Mark Van Doren, are in the audience as committee chairman Senator Oren Harris opens the hearing.

Ingrid: And so then especially it was important for a broadcaster like NBC to show their audience that, “Hey, we care about people, you know, we care about the education of future generations, and we’re doing, we’re proving that to you by having a cool show like Mr. Wizard on.”

Mr. Wizard: Watch Mr. Wizard. That’s what all the kids in the neighborhood call him because he shows them the magic and mystery of science in everyday living.

Alexis: Besides Mr. Wizard tell us where we’re going to go. What shows are you going to walk us through today?

Ingrid: So the shows I look at are The Johns Hopkins Science Review, which is the very, very first science program in the United States.

I look at Watch Mr. Wizard, which is the very well-known science program that airs in the United States. Nova, which is a game changer. I love Nova; it really changes everything as a science series. I look at 3-2-1 Contact, which is a program that was put on by the same people who put on Electric Company and Sesame Street, which is super fun, and Cosmos, which was put on by Carl Sagan.

The very first science show is called The Johns Hopkins Science Review. It starts in 1948. And it is produced, directed, and written by Lynn Poole, who is this sort of small, slightly owlish guy who doesn’t look like much, but he actually has this extensive background in modern dance and vaudeville and theater, which was why he was hired by Johns Hopkins University in the 1940s to be their public relations guru. And so he decides to help get this university national cred. He’s going to host a show that weekly looks at different issues in science and specifically talks to different professors at the university who are professors of engineering and medicine. And so it’s kind of a nice way to display what’s going on at Johns Hopkins University.

John Hopkins Science Review: The problem of water purification and the disposal of sewage is a problem the sanitary engineer takes care of for us. And it’s a problem that keeps us in good health. The science of sanitary engineering is one which requires great skill and knowledge, combining many different fields of science.

Ingrid: And so he has some cool guests on as well, like Wernher von Braun, who later becomes a host on Disney’s programs about space, and he’s, like, this German rocket scientist guy.

Alexis: And who’s watching this show: adults, kids, a mix?

Ingrid: It might help us understand that the main folks who are watching television in the 50s are wealthy, white women. And there’ve been some studies done saying that a lot of these women might have had scientific training. And so they were reading a lot of books about science, anyways. The market for popular science paperbacks actually increases substantially in this period. So you’ve got a lot of bored housewives at home basically. And they’re trying to do something. And so Lynn Poole figures that one thing that they might be interested in is having a show about science they can watch in the evenings.

And he actually himself is very much a feminist. He has women on his staff, his wife Gray Poole helps him write The Johns Hopkins Science Review, and one of the things that I really enjoyed researching is the way that they become this dynamic kind of power couple early on.

So again, it’s an interesting show. And again, it’s mainly for the family but with a special focus on women. And we can tell this because there are programs that are more coded feminine that are on air, about the science of dish soap, the science of training your dog, the science of using jewels, you know, diamonds in industry. And it’s an interesting show because again insomuch that they’re using a lot of these gendered subjects to talk about science, they are doing so in a way that is still respectful of women. They have a lot of women who are scientists on the program, and that’s unusual for the time.

But again, I think a lot of that comes not from, and this is where I’m very careful to delineate, it’s not because science was progressive in the 1950s. It’s not that. Science is not progressive in the 1950s. It’s because Lynn Poole was progressive in the 1950s. And so The Johns Hopkins Science Review is a show that very much goes back to this early vision of science, about science being wonderful and specifically looking at the ways that science can help you out in your daily life.

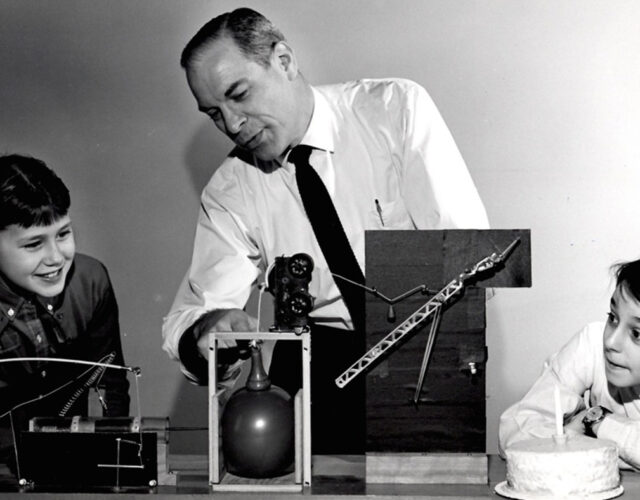

And that’s a quality shared by the other charismatic host of the science programs of the era, Don Herbert, who runs a show called Watch Mr. Wizard.

And Mr. Wizard is a youngish guy kind of in his 30s. He was a World War II bomber pilot, which is something that the newspapers make a lot of fuss about. They, you know, show pictures of him, you know, in his like bomber jacket. And Mr. Wizard, Don Herbert, actually is the first celebrity scientist. He’s the first person who becomes well known for his role as this actor playing a scientist on TV and because of that gets sort of a cult of personality around him. Lynn Poole who hosts The Johns Hopkins Science Review is a very interesting, charismatic guy, and he definitely hosts a program. He’s the focus and the face of the program, but he doesn’t have the same levels of adoration that Mr. Wizard has in the 1950s into the 1960s.

Watch Mr. Wizard:

Boy: Mr. Wizard!

Mr. Wizard: Hi, Doc. Stay right there. Don’t move. Close the door but stay right there because I have a problem for you. I want you to turn on the light. But before you do, I want you to see if you can estimate how long it takes from the time you flick the switch until the light comes on.

Alexis: What sets Mr. Wizard apart? I mean aside from the bomber jacket, which I love, why were people so into him?

Ingrid: I think the innovation really in Watch Mr. Wizard is that it’s especially on that point of explanation, that children can be explained to, they’re not lectured to. He thinks that kids can learn because he has young children at home. He’s trained as a teacher. He knows that kids can learn. And his innovation is that on screen he talks to children in this didactic way, where he isn’t lecturing at them. He’s saying, you know, things like, you know, “Why do you think that dish cloth turned blue?” You know, “What do you think happened there?”

And he gets the child to observe what’s going on, and then he corrects the child.

Mr. Wizard: Have you ever seen a real heart?

Boy: A real one? No.

Mr. Wizard: Ever handled—been able to examine one?

Boy: No, I’ve seen them in pictures.

Mr. Wizard: Well, today you’re going to examine a real heart. It’s over there in the refrigerator all waiting for you. And how about have you ever seen real blood circulating through real blood vessels?

Boy: No.

Mr. Wizard: We’re going to see that today, too.

Boy: Oh, boy.

Mr. Wizard: Are you ready?

Boy: Yeah, I guess so.

Ingrid: And in that way he sees the child as an equal participant in scientific discovery. And that’s very empowering for children at home because they get the signal they know that they’re being respected and that’s part of the reason that Mr. Wizard does so well, is that he signals that his audience at home is respected. And that’s a trait by the way, that I think is the key thing, is that in the shows that really succeed, they’re all based on an idea of trusting their audience, knowing their audience is intelligent enough to get what’s going on. Johns Hopkins Science Review respects their audience. On air, Lynn Poole will say lots of things about the smart people at home, you know, and one of the viewers actually writes in to Poole and says, “Hey, you don’t think we’re morons. Keep it up.” Watch Mr. Wizard, very similarly, the children are respected on air, and they write in to Mr. Wizard and they thank him for respecting them. And Nova similarly, the people who are putting Nova together don’t think that their viewers at home are idiots. Quite the opposite. They want to put together very interesting, intriguing shows.

Alexis: So what does Nova do that’s different from the other shows? What is it that makes them like stand out and be, you know, the big boss?

Ingrid: Right! Okay, so I have to take our listeners back to this dark era before public broadcasting exists just to set the stage for a moment, right? So, okay, let me go back to what’s in it for the corporate broadcasters, right? They’re looking for the money. They’re looking for the viewers. They’re looking for public trust.

And so what’s interesting is that corporate and commercial broadcasters are interested in educational broadcasting in the 1950s because they think, “Hey, maybe this will convince more people to buy TV sets.” And if people are buying TV sets for their little children at home to learn about colors from Ding-Dong Schoolhouse, then they’re going to be watching along for these other programs. And it works, until much like any sort of technological boom, everyone has TV sets. And that kind of happens by the late ’50s, early ’60s, and then commercial broadcasters generally start losing interest in producing these educational shows. And it’s actually a drought in science educational programming between 1964 and 1974.

Alexis: Wow.

Ingrid: There’s nothing really.

Alexis: Because at that point they’ve sort of achieved maximum saturation. So they’re like “meh, who cares.”

Ingrid: Exactly, and this is kind of a funny thing because this is the same period that the space race is happening in the U.S., right? So you’d think there would be like a weekly show about science, right? But there’s not. Instead you get a lot of specials. You get, like, one-off specials where they’re covering individual, where “they” being the commercial broadcasters, are covering maybe individual rocket launches. You get some interesting, you know, documentary shows like The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau and Jane Goodall’s work on National Geographic.

But there aren’t any regularly aired shows about what we would think of as laboratory science in the United States in this 10-year period. Nothing.

Alexis: So Nova comes along in the 1970s, and it’s a huge turning point for science on TV. How does it happen?

Ingrid: So you’ve got to think about the U.S. in the late ’60s, early ’70s, right?

Because again you had this golden age of scientific expression, if you will, in the 1950s, the 1930s, the 1940s, the 1950s. Sort of an adoration of science. You know, this whole idea that science is going to save us, right, because science has been saving us, right? I mean look, you know, you have things like the vaccination for polio that’s been invented, things, beautiful things that happen. DDT has saved us.

Well, I mean, not really, but they don’t know that yet.

Alexis: That comes later.

Ingrid: This is actually part of what happens is by the late 1960s there are books that are starting to be written like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, right? And there starts to be this important reporting that happens in the late ’60s about science that uncovers the true fact that science isn’t always good, that there are these problems that start happening, that there are these ways in which science and society aren’t always in tandem. They’re sometimes at odds, right? DDT isn’t all that good for you.

Alexis: Right.

Ingrid: Because what starts happening in the late 1960s is that not just scientists are talking about science anymore and not just in wonderful tones. People start being critical of the scientific projects, especially journalists. And so what happens is there is a group of journalists and documentary makers in England who are interested in science. And they’re interested in looking at science in this different way, that sort of humanistic way is how they think about it. And they create a program in the late ’60s called Horizon.

It looks at science sort of like, the sort of poetry of science, looks at some serious issues of science, and there are a bunch of young producers who are in this program. So again, nothing like this exists in the U.S. at this point. There’s a guy named Michael Ambrosino, who is American and he lives in Boston and he’s super involved in broadcasting in the ’50s and in the ’60s.

And he has dabbled a bit in science educational broadcasting in the ’60s. Then he gets a year-long fellowship to go to the BBC. And he’s basically told to do what all fellows are told, which is hang out with these people and see what you can pick up. And so he gets to hear about this cool program called Horizon.

Horizon: Horizon aims to present science as an essential part of our 20th-century culture—a continuing growth of thought that cannot be subdivided.

Ingrid: And so here’s about Horizon. He thinks, “Oh, we could do something like this in the United States.” And so he goes back to the United States, and he pitches the idea for a science series to this new thing, it’s a channel entity, it’s this thing called PBS.

This is where I’m going to go way back and say so, okay, so you know how I was telling you about commercial broadcasting?

Alexis: Yes.

Ingrid: Well, so that’s like the, you know commercial broadcasters are invested in commercial interests, right? So what happens in the late 1960s, there’s so much interest in, there’s so much frustration among American viewers that TV has become increasingly commercial, that they rally together, and they say why don’t we have a whole station, a whole channel, about education?

And they lobby, you know, and get the support of different senators and members of Congress and create something that’s called public broadcasting.

Alexis: Okay, so we have now public broadcasting, like that’s sort of building. This Horizon thing has already happened in England.

Ingrid: Yep.

Alexis: He goes over. He sees it.

Ingrid: He’s inspired.

Alexis: He’s inspired. Yeah, he comes back and is like hey, oh cool. We have this new station that needs educational content programming.

Ingrid: Yep.

Alexis: Have I got an idea for you?

Ingrid: Exactly.

Alexis: And so it’s, if I’m understanding you correctly, it’s also sort of like all the right things are happening at the right time?

Ingrid: Yeah, exactly. He’s in the right place at the right time, and he’s the right person. Michael Ambrosino is this dynamic producer, and he’s really good at bringing people together. So what happens is Michael Ambrosino gets the funding for the show, and then he’s like, “Oh, you know, hmm. I wonder who could do this series. What about, what about, I take some people from England with me, maybe they could help.” And so he goes to England. He poaches a bunch of people from Horizon basically. But there, but this is again, this is to try to understand, we have got to think about the cultural context.

So it’s the early 1970s in the U.K., and the economy in the U.K. is not all that great. Actually, there’s actually a mass exodus of people who are younger, and you know coming out of the U.K. in general going into different fields. And so he’s pretty able to find some younger producers, people in their late 20s who say, “Yeah, living in the U.S., that sounds like a great idea. I’ll go do that. Yeah, why not?”

And they have experience, again, in Horizon. They’re interested in creating another television program that isn’t just about the wonders of science, that looks at science critically, that looks at the ways that science interacts with society.

And so this is the point that I’m trying to drive home a bit, which is that Michael Ambrosino brings with him a group of people who come out from a different tradition of broadcasting. They’re from this very British model, which by the way interestingly does not look at itself as being educational. At that point in the U.K., science broadcasting was an informational act. It was not educational.

Alexis: So there’s no, there’s no perspective. They’re just trying to tell you like this is what it is. These are the facts in order, not so much “we want you to feel good about science when you’re done. We want you to smile. We want you to pursue it.” Like it’s, it sounds like again, it’s really opposite from what’s happening in the U.S. during that golden era of science, where it’s very much about like creating a super-specific narrative about science and scientists, and yes, they are exalted, and they’re geniuses who will save us all.

Ingrid: Exactly, the English model does not say that these people are geniuses. The English model says, “Oh look, there’s some people who do science; isn’t that great or maybe not so great. Look what they’re doing.”

<Laughter>

This is something I found whenever I talked to someone who was again, a producer from that original set of English producers who were brought over. Which is, I would start by saying how is Nova educational? And they say, “Stop right there. Nova was not educational.” And I would be like “What? Huh? This is, my American mind doesn’t make any sense of this.”

And they’d be like, no, because again according to this British tradition, it’s about presenting information in a way that you, the audience member, can judge.

Alexis: So if it is coming at the same time that we are starting to reflect on what science is actually doing, right, science and the news journalism are starting to pick up the story. Silent Spring is out there. Nova is coming along.

Ingrid: Oh, and one other important thing, which is very important; Vietnam is in full swing. And there’s a science journalist who writes in the mid-1960s. He’s a professor of science journalism at Columbia. And he starts complaining about the ways that newspaper folks are not paying attention to science anymore.

He says, “Oh, you know, everyone’s focused on Vietnam. What’s the problem?” And also there’s civil rights. He’s like, you know, there’s just not the focus on good old science broadcasting anymore. People are focused on these other things. What’s going on? But that’s an important thing: people, people in general in the United States, are worried. And they’re also starting to be very suspicious that they’re not being told the truth.

Alexis: Right. And so that’s a different—

Ingrid: This is the audience for Nova, a group of people who are slightly suspicious of the ways that science has been packaged to them for the last 15 years, and especially younger people, right? This is the group of children who grew up watching Mr. Wizard have now seen their friends sent to Vietnam. And they’re a little jaded. And not quite as trusting as they were in the 1950s.

Alexis: Right. So in some ways we’re talking about what made Nova different.

Ingrid: We are, yeah, so different.

Alexis: But in some ways we’re also talking about how the world is different. Right? And so like Nova then becomes informational and critical and is packaged in a completely different way, but it’s also like it’s matching up exactly with what the audience, like, wants and feels like they need at this moment in time.

Ingrid: Absolutely.

***

Advertisement:

Alexis: Hey, listeners, we have some exciting news: this October, Distillations podcast is coming to you with our first live show. We will be at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia, and we are going to be exploring the spooky side of alchemy.

Lisa: And early modern science’s flirtations with ritual and the occult.

Alexis: We’ll bring the patented analysis and observation that you’ve come to know and love.

Lisa: So join us for the great storytelling, stay for the candy, and go home with a prize from one of our eerie games. Like maybe a philosopher’s stone. We can’t guarantee that it will work.

Alexis: The show is happening Wednesday, October 30, at 7:00 p.m. Tickets are $10, and you can get yours now at science history.org.

***

Ingrid: Nova in the 1970s is very much like a very serious documentary program. It feels more like Frontline would feel today. It’s about the critical issues of science. In the first season they don’t pull any punches.

They are the very first people to critically look at the story of DNA. Now Nova is a joint production between WGBH and the BBC because what they end up working out is a deal where the fledgling GBHers can use a certain amount of material from the BBC, and they will give some material to the BBC in return.

So they share episodes back and forth. And one of the episodes they have material for is an episode about DNA, about the double helix, and how it was discovered by Watson and Crick and Wilkins, and this old story, right? And early on they’re like “Huh, what do we do?”

And so they asked one of the founding members of Horizon, a guy named Robert Reed, what his take is on it. And Reed reads through the material that they have, he kind of screens the material. He says, “You know, there’s really nothing new here, except if you look at the story of Rosalind Franklin.” And the producers of Nova are like, “Huh? Well, that’s an interesting idea,” and they let it sit for a bit.

And then one of the people who’s a science editor actually at Nova at the time is a guy named Graham Chedd. And Graham Chedd looks at the material and says, “No, actually we should, we should do this. We should look at Rosalind Franklin and her impact on the discovery of the double helix.” And he reads a book that has just come out. It’s the very first book on Rosalind Franklin. And it was written by one of her good friends, and I think it comes out around 1975, 1974, it’s about then.

And everyone at Nova reads it, and they say, “Oh, yeah, this is really good. This is a really interesting story. Wow, Rosalind Franklin had these materials stolen from her; this is terrible.” And so they start writing this new script basically, and as they look at the footage, because they have all these interviews, they’re like, “Huh, we need someone to tell, tie the story together. And Graham Chedd says, “We need someone who Americans are going to really listen to. What about Isaac Asimov?” And everyone’s like, “Oh, let’s see if we can get Isaac Asimov to do this.” Now this is unusual because Nova doesn’t have a host.

Nova still doesn’t have a host. Right? So that’s one of the things that kind of makes Nova, Nova. But they decide to write Isaac Asimov, and they’re like, “Hey, Isaac, we have this unusual story about Watson and Crick. Would you be interested in hosting it for us?” And Asimov at first says, “Eh, I don’t know guys. I mean really, yeah.” And then his wife gets involved. Janet Asimov basically convinced Isaac Asimov to host a program because she’s a huge fan of Nova, and he’s like, “Okay, guys, I’m gonna do it. I know it’s important.” And they’re like, “Okay, great. We’ve got Isaac Asimov on board.”

Nova: (Asimov) It’s the story of a race and of the people who participated in it wittingly and in some cases unwittingly. The race was to discover the true nature of the gene, the secret of life. The winners were these two men, James Watson and Francis Crick.

Ingrid: And so they film him wandering through basically what looks like a DNA park at Cold Spring Harbor. It’s really cool. It’s like kind of these giant, you know, features of like giant DNA molecules outside. He wanders around, and he sort of explains this overarching story about Rosalind Franklin. And because he actually also reads the book that they have all read, and he says, “Wow, she was really taken advantage of. This is terrible.”

And so the resulting episode is called “The Search for the Double Helix,” and it comes out in 1976. And it is, man, it’s kind of a hoot.

Nova: (Asimov) As a result of the contents of Watson’s book Double Helix, the impression has arisen that Franklin was an ogre to work with, but this is not so. Both before and after the events of the double helix, those who worked with her found her delightful.

Ingrid: It’s basically Watson and Crick reminiscing about the ways that, you know, they discovered DNA, and then they’re asked all these awkward questions about Rosalind Franklin. And they say things like, “Oh, Rosalind Franklin, you know, she just didn’t play fairly.” And Watson keeps on saying things about, you know, “She tried to kick me several times. She tried to throw things at me,” you know. “Didn’t she?” And, you know, Wilkins who was, they cut then to shots of Wilkins. He was like, “Well, I think Watson’s exaggerating a bit.”

Nova: (Watson) She came toward me. I thought she was going to hit me. So I quickly got out, at which point Morris was coming around and she almost hit Morris.

(Wilkins) I don’t think anybody hit anybody; actually some people may have thought someone was going to hit somebody.

Ingrid: But what is interesting about this particular episode is that it really puts on display the ways that these three scientists, who are held as the paragons of discovery, are actually pretty complicated individuals, right?

And that scientific discovery is not clear-cut. It’s messy. And often, sometimes, it involves taking advantage of other people. And so, again, Isaac Asimov does a really good job with some intercuts saying, “Well, of course, Rosalind Franklin also was involved, blah blah blah blah blah.” And the episode comes out in 1976, and people really think it’s great.

And, well, pretty much everyone, except Francis Crick.

Alexis: Well, yeah, I mean … And other people!

Ingrid: I know for sure Francis Crick doesn’t like it because he writes to Isaac Asimov shortly after it aired, and he says, “Dear Isaac, wonderful job on this episode, blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. You know, I’m not sure if you got the part about Rosalind Franklin right. She was actually a little prickly to work with.”

And Asimov writes back sort of basically smoothly, you know, saying, “Well, you know, that was a complicated story. We did a really good job presenting it, right?”

He completely does a great job sidestepping Crick in his reply. But again, this is a good example of how a show like Nova really takes a different point of view on a scientific controversy. They actually are one of the first programs to present the controversies in science.

Alexis: That sort of blows my mind. I mean, I think I’m still trying to understand why Nova and why then?

Ingrid: So number one is that public broadcasting exists and because public broadcasting exists, you can have a show on television that is not beholden to sponsors, right? And that’s really important actually, that science shows before Nova are really beholden to sponsors because they have to be funded every week. And in order to be funded by, you know, Alcoa or something like that, you have to speak positively about science. Nova doesn’t have to do that because Nova is the first program to be, to get funds from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and to get funds from the National Science Foundation. And so they’re free. They can speak truth to power in a way that other science programs aren’t previously.

So reason number two that Nova is in the right place at the right time. They have an audience who’s primed to watch this hard-hitting content because of what I’ve mentioned beforehand. The audience is suspicious that they’ve been lied to by people, you know, in positions of responsibility: the government, you know, scientists, corporations, you know. This is a group of jaded baby boomers, right? This is the dark side, you know; this is basically Watergate, right? This is a group of people who have seen their idols tarnished.

And another reason. Reason number three is a technological innovation, which is you can have cameras outside of the studio. You can have these programs really be documentaries that bring you into the action, that just, you know, don’t keep you in like this little box that is a studio set, which is like totally corny and everybody knows, everybody knows that studios are corny in the 1950s. Like, you know, everyone knows it’s all kind of hokey pokey.

And so that’s why in the 1960s, actually in the ’60s, during this dearth of science programming, that’s one of the reasons that you get this really interesting programming at Nova. Nova takes you into a nuclear power plant.

Alexis: That’s very cool.

Ingrid: So this is an interesting episode because it’s based off some very serious good reporting about the ways that nuclear materials are not safely contained in nuclear facilities around the United States. It supposes that the materials, that the information needed to build a bomb is actually freely available at a lot of sort of scientific establishments and in academic libraries. That’s one thing it supposes.

The second thing it supposes is that the material physically needed to make a bomb is not safely contained within nuclear facilities. That it would be easy for a terrorist to come in and seize material, basically. And so a very serious episode of Nova. And it’s narrated by Robert Redford, who has recently come off of a film on Watergate, right?

So sort of cueing the audience into this idea that, “I don’t know, should we trust science or not? You know, should we trust the scientists? Right?” That’s more of the point.

Nova: (Redford) This is Stockholm, the crucial link in a frightening story.

Ingrid: The Nova staff actually hire an MIT student to comb the stacks of MIT to see if they can build the plans for a bomb from scratch.

This guy’s actually able to do it.

Nova: (MIT student) I was pretty surprised at how easy it is to design a bomb. When I was working on my design, I kept thinking there’s got to be more to it than this, but actually there isn’t too much to it. And in fact the design I came up with is a lot like the one they first tested, the bomb they first tested at Alamogordo.

Ingrid: That’s kind of scary. And there’s so much buzz about this episode that in fact they get a lot of pushback, and one of the people that Nova gets pushback from is the National Science Foundation. You remember how I said they got funding from the National Science Foundation? And that’s important because that’s no strings attached, that’s money that they can use to fund their programs because there is no particular ideological bent. Well, it turns out that wasn’t quite true because the National Science Foundation says, “Hey, what are you guys doing? This is not a positive portrayal of science. You’re making the scientists look like idiots here”—and threatens to pull funding of Nova at that point. They’re like, “You guys messed up, you’re done.”

And Michael Ambrosino, who is the executive producer and founder of Nova, is, you know, not really floored. He talks to the members of the National Science Foundation who he’s in correspondence with and says, “Fine, if you guys do that, we’ll let everybody know that the National Science Foundation has an agenda. And just watch, we’ll tell every newspaper in the country what you did.” And then they back down.

Alexis: Smart.

Ingrid: So yeah, I mean again, so this is in terms of the ways that, you know, funding is important and especially the way that a show like Nova really is pushing against the grain and a way to, because they really respect the story that they’re telling and that they know that their audience, who they respect highly, wants the truth, and they think their audience should know what’s actually going on.

Alexis: So Nova changes the landscape for science programming for grown-ups, but can you walk us through the evolution of how that becomes science programming for kids? I mean the last thing we talked about, right, is Mr. Wizard, which is fun and great. But how does that become the science programming that we know today for kids?

Ingrid: In the 1970s you have Nova, and they’re really interested in creating this like hard-hitting content. And then you have a group of educators and television producers and writers which coalesce up in New York City and become the Children’s Television Workshop. And this is a group of people who are really interested in creating content and educational material for young children and finding ways to present a, I think, more positive, upbeat vision of the future for these young kids.

And so, yeah, so CTW, as this group becomes known, launches their very first series in 1969, which is known as Sesame Street.

Sesame Street: (theme song) Sunny day. Sweepin’ the clouds away. On my way to …

Ingrid: Super fun, right? Yeah. Yeah. Awesome. Yeah, and it’s a hit! Sesame Street is like a smash hit like, you know, by the early 1970s every child in America knows who Big Bird is. And so Children’s Television Workshop rolls along with another hit series called The Electric Company.

Another smash hit, like people love The Electric Company. It’s got Rita Moreno. It’s this really cool, you know, bopping program that teaches early literacy skills. And so the people who put together that program say, “Hey, couldn’t we do that about science? That’s an idea.”

And so they spend a couple of years brainstorming this program that eventually becomes known as 3-2-1 Contact.

3-2-1 Contact: (theme song) Three! Two! One! Contact, is the secret, is the moment …

Ingrid: What’s kind of cool, again this is a story about technology, is that by the early 1970s you’re starting to come up with these kind of cool, computerized tools that can be used to measure viewer response.

You don’t have to just, you know, input letters anymore. You can have a child watching a program like Sesame Street and holding this thing that kind of looks like a calculator. And whenever they like anything that happens on screen, they’ll press a button and, like, the mother computer will measure the exact time that they press the button and that response and then that information can be fed into a master spreadsheet and used to create a graph that shows not just when Susie pressed that button but also when Ricky pressed that button, to see which kids responded well, like moment by moment, to an entire program.

So yeah, so CTW uses this sort of data to create Sesame Street; they use it very well to create The Electric Company. So it makes sense that they’re going to use this data to create something that is a science show. The most interesting study that they do, I find, is this television research interest survey, where they survey around 4,000 children nationally, ages again about 8 to 12, about what they’re watching on TV in 1975. And it’s amazing. It turns out kids are watching a lot of Happy Days. They love Wonder Woman. They’re interested in, you know, Little House on the Prairie and the Bionic Man. But one thing that is concerning to the viewers, well, to the people who are understanding the viewer responses, is that these kids are not really watching any science programming.

So in this period there were a number of sort of, kind of science shows on air, including one that is a pseudoscience show called In Search Of. And In Search Of, for your listeners who don’t know it, is a show that is hosted by Leonard Nimoy, who was Mr. Spock in Star Trek. And every week he has a serious look at a scientific issue like—

In Search Of: (Nimoy) It is felt by some scientists that Bigfoot falls somewhere in this progressive chart of man. A giant hominid related to but not like modern man. According to this theory Bigfoot would have pursued a course of evolution separate but parallel to his human cousins.

Ingrid: And so what the survey done by CTW shows is that in 1975, which is when you have shows like Nova on air, there were more kids who are watching In Search Of than Nova. And so that’s probably, probably skewing what they’re really thinking of as science. So that’s like the most serious thing that they find, and that makes everyone very uncomfortable and very unhappy, and it really propels this research for that because they say sort of “oh, you know, crud. We actually need to get a science show on air the kids can watch.” So they spend I think two years doing research, and then the research team hands the information over to the writers. At the same time, they’re also trying to develop and get information from particular communities, right?

So they survey African American scientists and Latino scientists, and they try to find a group of Asian American scientists to interview as well to get a sense of what ways that people in those communities think that the science—on scientists specifically—on the shows should be represented.

So 3-2-1 Contact is a program, yes, put together by committee; it is very Kumbaya. I mean what else would you expect from the people who put together Sesame Street, right, you know? They have this positive image of America. And I think everyone who joined CTW in those years was very, very young and very idealistic. They really thought they were helping to make the world a better place. They knew they were helping to make the world a better place.

3-2-1 Contact: (theme song) Three! Two! One! Contact is secret, is the moment when everything happens! Contact is the answer, is the reason that everything happens …

Alexis: One of the things I’ve been thinking about, listening to you talk, is that, you know, there’s all these people who are talking about science on these different TV shows. And it’s really a whole spectrum. But you know, we kind of got two main camps, right? You got your bomber jacket–wearing celebrity hosting Watch Mr. Wizard and then on Nova, you know, it’s actual scientists, sometimes graduate students imparting information. And then comes Carl Sagan, right? He sort of shifts the paradigm; he doesn’t say he’s going to be a scientist or a science communicator. It’s kind of like, I can be both.

Ingrid: Can I just like start by saying that researching Carl Sagan was really fun because a huge part of the research was sitting in the Library of Congress for two weeks watching footage of The Johnny Carson Show. So I got to watch a lot of The Tonight Show back to back. That was great. But no, in all seriousness, that was great because I got to watch Carl Sagan over the course of a couple of years refine his on-air technique.

Carl Sagan was certainly not a novice when he started Cosmos in 1980. I wonder whether he had always been interested about being in the public eye because he certainly was very involved in the early days of broadcasting.

He was on television as a high schooler on a quiz show in New York. And he was also on the radio as a young, young man in 1962. He’s on a program called Voice of America, which is very big in the ’60s. And one thing that survives is a pamphlet of that era, and he’s got his hair slicked back, and he’s kind of got the starry-eyed expression in his face. And you think he’s just looking in the future, thinking one day, one day I’ll be on TV. I’ll have my own show.

And so he works very hard at refining his public persona and public speaking technique throughout the 1960s. He is constantly, in that period, he is being called upon to be a voice of professional astronomy on programs. He’s spoken to a couple of times by Walter Cronkite. And one of the interesting early interviews, actually it’s done by, I think it’s Cronkite who is interviewing Sagan and another person who is wearing an eye patch and smoking a pipe. And it’s a very strange interview because despite the way this other guy is dressed up, your eyes are still drawn to Sagan. Sagan is really dynamic; he’s really got your attention.

And then by the late 1960s, early 1970s, Carl Sagan goes through a period where he starts presenting himself in more of a, I would say, more of a suave astronomer way. So it’s in the late 1960s that he starts wearing a turtleneck in his public appearances, and I can tell you for sure what year that is: that is 1968. I have tracked it. I don’t know why, but it’s something that I’m very interested in.

I can tell you that one of the first places that he starts wearing the turtleneck-coat combo is in Portland, Oregon, actually. He does a series of lectures in Portland in the spring of 1968. It’s his first professional lectureship. It’s three weeks of conferences, three weeks of public lectures around the state of Oregon. We have dialogue from those conferences which is really exciting. What happens is there is sort of a stirring, if you will, among scientists who are interested in presenting to the public. And this goes back to the Nova thing because they’re thinking about the audiences for science broadcasting. Audiences are looking for something more.

They’re looking for something that’s more, more hard-hitting, again more authentic. Let’s get back to that word, authentic. They’re looking for authenticity in a way they haven’t gotten in the 1950s and even in the early 1960s. And they’re looking for new people to tell them about science. And so from this mixture you get a couple of voices like CTW, you get Nova, but you also get Carl Sagan and his peers. And there’s a group of people who are dubbed the visible scientists who start speaking to the public in this period. They are not being policed by professional norms in the way that they would have been in the 1960s and earlier. They’re being willing to go and actually talk to the public without any sort of mediation. They don’t need a journalist to tell the public what they’re saying.

Alexis: There’s a surprising person, right, that has this big role in making Carl Sagan the man we’ve all come to know and love. Can you tell us a little bit about that? And spoiler alert, I’m talking about Johnny Carson.

Tonight Show: (Carson) My next guest, I always look forward to having him here. He is a professor of astronomy and space sciences at Cornell. Would you welcome please Dr. Carl Sagan?

Ingrid: So what happens is that Carl Sagan writes a book called The Cosmic Connection, and The Cosmic Connection comes out in the early 1970s. And it’s a collection of Sagan’s earlier speeches around the country, namely in Oregon actually. And so Sagan is interested in promoting this book, and it is with a major press and so they’re helping him promote the book. Now Johnny Carson has a number of people in his program who recruit talent to appear. And one of the recruiters knows that Carson is really into astronomy.

And he hears about this book and he’s like, “Oh, great. We’ll have an astronomer on. Johnny’s gonna love that. That’ll be great.” And so they have Carl Sagan on in November of, I think it’s ’73 or ’74, and Carson loves him. Carson thinks that Carl Sagan is kind of a cool guy. And the first interview it’s a little bit stiff.

The way that these interviews work, they normally give the questions out beforehand, and the guests are required to submit their responses to the questions. And that way they kind of know what’s going to happen during the show. And so Sagan does that. And what’s interesting to note is that for the other interviews, that’s not done. Carson tells the person who books Sagan, “No, no, don’t give him his questions beforehand.” He doesn’t need to have this formal response.

And this is where I should say that a lot of what I am looking into and what I comment on are the ways that Sagan and Carson appear together on air; so this is where again, as a historian of broadcasting, my hands are somewhat tied here.

I know that Carson and Sagan started hanging out together because I have, you know, reminiscences with both of them where they talk about how they would have dinner after the shows. But there’s no correspondence here. So some of this is what I’m just observing from watching their interactions over a year on television.

And again what’s fascinating is that over the course of the year, Carson has Carl Sagan on his program seven times. And that’s very unusual. That’s especially unusual for a scientist. No other scientist is on that frequently. And so again, I assume that Carson really liked Sagan. That’s my assumption here.

And what’s interesting is that in the dialogue, you know, initially, you know, Carson will ask Sagan a question. Sagan will respond. But Carson’s really leading the patter. Carson’s the one who’ll crack a joke. Sagan will say something. Carson will say, “Oh, isn’t that funny, such and such and such.” And he will really lead Sagan through that portion of the interview. And the interview is not necessarily long; it’s like a 20-minute interview. And Sagan usually has the last segment, which is usually when people who are watching The Tonight Show will be asleep. So let’s be honest. But what’s interesting and what I found was fascinating was that over that course of, you know, seven interviews, Sagan would repeat material sometimes from earlier interviews, and as he would repeat it, he would get more laughs. He learned how to rephrase some of the delivery of these, you know, factoids about astronomy, and he and Carson were both very passionate about the importance of educating the general public about science. And they would have discussions about that on air, about the importance of science and the importance of developing a grounded idea of science.

But they would also have, you know, conversations about fun things, about, you know, do aliens exist, extraterrestrials? There’s a person named Erich von Daniken who is very popular in this period in the late ’60s, mainly for his theories on how aliens must have built the pyramids.

And Carl Sagan is regularly on, taking Erich von Daniken down because, as he says, you know, the only reason von Daniken really believes that is he doesn’t think that anyone, you know, anybody could, you know, specifically anyone who’s not white could build pyramids. But of course people can; of course, you know, ancient civilizations of people who are non-white have done amazing things.

So it’s actually this interesting thing where Carl Sagan, through the ways that he takes down von Daniken, really comes off as, and he is, an urbane, you know, socially focused, progressive astronomer. And specifically unlike again earlier generations, he is not afraid to talk about the ways that scientists are interacting with society.

And so Carl Sagan is on alongside, you know, legends of the 1970s like the Osmonds and, you know, he’s on alongside comedians and famous actors. And he gets just better and better, I would say. And I think by the end of it, he’s really the one who’s cracking the jokes, and Johnny lets him do that.

In a look back at sort of celebrating the last year of Carson’s program, of Carson hosting The Tonight Show in the 1990s, Sagan writes that he’s not sure initially why Carson has him on. He doesn’t know why Carson likes him so much. And then as they’re exiting the soundstage one evening going out for dinner, Sagan, you know, they’re walking through a door, and one of the guys who is on the soundstage sweeping up stops Sagan and says, “Hey, I really loved you in that episode, you were great. I really learned something.” And as they leave, Carson points to the guy and says to Sagan, “That’s why I have you on every night.”

And so really what Carson saw in Carl Sagan, I think, was this ability to connect to audiences and to be authentic with audiences.

So my favorite Sagan clip to play of this period is where Sagan is reviewing Star Wars. And he talks about— It’s the first Star Wars, and Sagan is like

“It wasn’t all that realistic. It was an okay film.”

The Tonight Show:

Sagan: Star Wars starts out saying it’s on some other galaxy, right? And then you see there’s people, and starting in scene one there’s a problem because human beings are the result of a unique evolutionary sequence based upon so many individual and likely random events on the earth.

In fact, I think most evolutionary biologists would agree that if you started the earth out again and just let those random factors operate, you might wind up with beings that are as smart as us, and as ethical, as artistic, and all the rest, but they would not be human beings. That’s for the earth. So another planet, different environment, very unlikely to have human beings.

Carson: Yeah. Are you saying on another galaxy it’s not possible that there could be—

Sagan: It’s extremely unlikely that there would be creatures as similar to us as the dominant ones in Star Wars. And it’s a whole bunch of other things. They’re all white. The skin of all the humans in Star Wars, oddly enough, is sort of like this. And not even the other colors represented on the earth are present, much less greens and blues and purples and oranges.

Carson: They did have a scene in Star Wars with a lot of strange characters.

Sagan: Yeah, but none of them seemed to be in charge of the galaxy. Everybody in charge of the galaxy seemed to look like us. And I thought there was a large amount of human chauvinism. And also I felt very bad that at the end the Wookiee didn’t get a medal also.

You know, all the people got medals, and the Wookiee who’d been in there fighting all the time, he didn’t get any medal. And I thought that was an example of anti-Wookiee discrimination.

Alexis: So we talked about The Johns Hopkins Science Review, Watch Mr. Wizard, Nova, 3-2-1 Contact, Carl Sagan, and I mean, what I’m really curious about, what I want to get into is, what does that tell us about who gets to communicate science?

Ingrid: What’s interesting is that in the 1950s, the 1960s, most people who were in science broadcasting were not scientists, right? Most people aren’t. There’s a good study done by Hilliard Krigbaum, who shows that most people who are doing science writing have some background in science because they’ve taken some undergraduate classes in science.

This is the 1950s, and all you needed was an undergraduate degree, right? In fact, that was like amazing if you had one, again different times, and that’s actually an important distinction. It’s a question of how much science do you need to know to do science broadcasting because what happens is by the 1970s and the 1980s you get from the sense of, oh, you can be kind of vaguely aware of science to this understanding that, no, you need to know how, you know, mitochondria function in a cell, and that’s the only way you’re going to be able to explain science to somebody who is a nonscientist.

Alexis: I see.

Ingrid: And so part of that, now mind you, is connected to something that has nothing at all to do with actual storytelling. It has to do with numbers. It’s a numbers game. And this is the issue where in the 1960s there is a whole bunch of people who are pushed into of all things theoretical physics. Amazing, right? It’s because there’s a lot of support in the late 1950s, early 1960s, for young people to become theoretical physicists. And actually, this is an interesting story with 3-2-1 Contact, and Rigo, you might remember this. I kind of mention that there are so many people who have come into science in the early 1970s, there were too many theoretical physicists. Turns out we don’t need that many, and so there is a bizarre moment in 3-2-1 where you have scientists who say to the creators of 3-2-1 Contact, “No, we shouldn’t do the show. We don’t need any more scientists.” And they’re like, “Wow, what? Where does that come from?” And that came from this idea that they had created too many scientists. So what happens to all these scientists? Well, a lot of them say maybe we could be science communicators.

Suddenly these shows that are about science receive quite a few CVs and cover letters from X, Y, or Z scientists who say, “Hey, I’m looking for a job. I’m in my early 20s. I have a doctorate in physics. I think I can write for you guys. Like, I know how to write, right?”

And so if we go to today, right, we are in an economic moment where there are again lots of people with graduate degrees, in both the humanities and the sciences, mind you, who are having a hard time finding work. And in the sciences a lot of people, especially people who have been burned out or for good reason decide that they want to leave science, who say, “Hey, I want to do something else with my life. I bet I would be great at science communication.”

Alexis: But it’s different in that it’s not solving, I mean, it’s solving a problem, but it’s not the problem necessarily that the audience needs solved in the same way that the audience for Nova in the ’70s—

Nova is like solving a problem for them. And so it feels like we’re in this weird moment where we’re sort of in this circle where, like, we say we need to communicate science and science communications is so important, but we keep narrowing the field of like who gets to do that communication, and what they look like, and how they talk, and what kind of background they have. But then we say, “Oh, no one’s interested in listening to science blah blah blah.” It’s like it’s a loop.

Ingrid: It’s a loop, and some people who are great science communicators are listening to this problem. Again, I think about the people who are over at Stony Brook University, right, who are at the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science. It’s a program that was founded not surprisingly by two producers from Nova, John Angier and Graham Chedd, who work together with Alan Alda, who is an actor, to focus on the ways that people who are non-scientists have something to offer to scientists, namely communication skills.

And so, but yeah, there is this tension. And again, I want to say I’m very, I’m not saying people who are scientists don’t make good communicators. They definitely do. People who are scientists are great communicators. I think people who tell stories are people who tell stories; it doesn’t matter the credentialing. But in terms of looking at the moment that we’re in, if your listeners are saying, “Hey, why are there so many, wow, why are there so many science shows going on right now?” This is part of the reason, is that there’s just a lot of people who are scientists who are really trying to carve out a niche for themselves in something else because they need a job.

Alexis: The thread that I saw running through all of, like, the work that you’re looking at and your entire dissertation and a lot of the conversations we had is who owns science communication? And that feels like it changes over time.

Ingrid: Yeah, it totally does. Yeah.

Alexis: And I think that feels to me like the key of what you’re tracking, and based on who owns it, that changes then what we define it as, what’s valued, what’s not valued, what’s popular, what’s not popular. But like, the people who are being communicated to are not the owners. They are clearly not part of that equation.

Ingrid: No they’re not. That’s the thing, is when they are part of the equation, the series takes off. That’s the thing. If you can make that, if you make the audience, if you respect your audience and you make them part of the equation, then they’re going to love what you’re doing.

Alexis: Distillations is more than a podcast. We’re also a multimedia magazine. You can find our podcasts, videos, and stories at distillations.org, and you can follow the Science History Institute on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

This interview was produced by Rigo Hernandez and by Mariel Carr. For Distillations, I’m Alexis Pedrick. Thanks for listening.