ALS is a fatal neurological disease that kills motor neurons. Even though it was first described more than 150 years ago, there is no cure, and the few drugs available only dampen the symptoms or slow the progression by a few months. In recent years new drugs have emerged. However, there is one problem: the life expectancy is just two to five years after diagnosis. This timeline is incompatible with the FDA drug approval process, which takes years and even decades. This has created a tense situation for desperate patients who are demanding the FDA approve unproven drugs. What’s the harm in giving desperate patients an imperfect drug?

Credits

Host: Alexis Pedrick

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

“Color Theme” composed by Jonathan Pfeffer. Additional music by Blue Dot Sessions

Resource List

“Luckiest Man” from the Baseball Hall of Fame

Choose Your Medicine: Freedom of Therapeutic Choice in America, by Lewis A. Grossman

How to Survive A Plague (2012)

“September 7, 2022 Meeting of the Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee” from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

“By narrow margin, FDA advisory panel concludes Amylyx ALS drug hasn’t proven effectiveness” from STAT News

“FDA approves ALS drug from Amylyx, giving patients a much-needed treatment option” from STAT News

“When Dying Patients Want Unproven Drugs” from The New Yorker

Transcript

Alexis Pedrick: In 1996, Cathy Collet was at her mother’s home in Indianapolis for Thanksgiving, when she noticed something was off.

Cathy Collet: Mom was 78 years old. I noticed when she was working over the sink in the kitchen, her head would drop. And, um, didn’t think too much about it, except there’s an adult child when they see their parent aging. It’s, you know, it’s hard. You don’t want to see that. And it’s like, oh, what’s going on? Then a few months later, her speech started to slur. And mom wasn’t one to like to go to the doctor, but it’s like, mom, you need to go to the doctor.

Alexis Pedrick: The doctor ordered an MRI and said that Cathy’s mom had had a small stroke. He gave her a low dose aspirin and recommended speech therapy.

Cathy Collet: And I don’t know if you remember the actor Kirk Douglas, but he had a stroke right about the same time. And that was mom’s kind of benchmark. If he can get well, I can get well. And mom worked very hard on speech therapy, but her speech just kept getting worse and worse. She worked harder and her speech was getting worse and worse. So after six months of speech therapy, her speech therapist, who was a wonderful young woman, contacted me and said, get her to a good neurologist. Her speech therapist knew something was going on.

Alexis Pedrick: Cathy found the best neurologist she could at Indiana University Medical Center.

Cathy Collet: So got Mom in the next day thinking we’ve got some kind of a weird stroke thing going. Mom said a few words to the neurologist and he said, “Who told you you had a stroke?” There was something about her speech that didn’t seem quite stroke-ish to him. So he took the MRI that I had gotten from the other doctor’s office the day before, and he put it up on the light box and there was a grease pencil circle on the MRI of her brain indicating the small stroke. And the neurologist, the minute he saw that, he said, that part of the brain has nothing to do with speech. She had had a small stroke, but it was a complete red herring to what she was experiencing with speech. She lost weight. She was choking all the time. It was a complete red herring. He diagnosed her that day that it was ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease, and it’s serious.

Alexis Pedrick: ALS stands for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and it’s also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease because of the famous Yankee baseball player who had it and made it known to the world.

“Luckiest Man Alive” Archive: First baseman Lou Gehrig hung up an amazing mark by playing in 2,130 consecutive games. Then a fatal disease attacked baseball’s Iron Man. In Yankee Stadium, touched to tears by the tribute, Gehrig made his last public appearance. For the past two weeks, you’ve been reading about a bad brag. Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.

Alexis Pedrick: ALS is a rare and fatal neurological disease that kills motor neurons. Eventually, it reaches a person’s lungs and throat, and they can no longer breathe. The life expectancy is two to five years after diagnosis. After her mom was diagnosed, Cathy immediately went to work figuring out what the treatment would be. She thought about when her aunt had breast cancer, and she found a good doctor and lived a long life before she died.

Cathy Collet: That was always kind of the model that we had. If you have a serious diagnosis, find the best center you can and give it a good try.

Alexis Pedrick: Cathy had worked for the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly for 18 years, so she tapped into that knowledge.

Cathy Collet: I have an old Merck manual.

Alexis Pedrick: This is basically a medical journal.

Cathy Collet: So I opened up the old Merck manual to look about ALS to find out more about ALS. And it’s like, the prognosis isn’t good at all. And it’s like, oh, this is an old Merck manual. I mean, that Merck manual was probably eight or nine years old. This can’t be right. So I got on the computer that night. I stayed up half the night. And this was back when you did dial up and CompuServe and things. But trying to find, and I found a message board where people with ALS were exchanging very helpful things with each other. And I noticed that after so many months, there would be an announcement that this is Mary Smith’s daughter, she passed away last night. And it’s like, I got the feeling inside that this is horrible.

Alexis Pedrick: The more she looked, the worse the picture got.

Cathy Collet: As I went looking for things for ALS, there was just nothing.

Alexis Pedrick: Cathy was upset, but she and her mother wouldn’t give up.

Cathy Collet: So, Mom wanted, asked me one Saturday if I would stop at Walgreens and get her some liquid vitamins. She was having trouble swallowing and she thought liquid vitamins would be better to try to get her vitamins up. Cause she read someplace that vitamin E might be helpful.

Alexis Pedrick: On the way to the drugstore, Cathy went to the library and checked out the biography of Lou Gehrig, written by his wife, Eleanor Gehrig.

Cathy Collet: And so I’m driving home and I have my stack of books on the front seat of the car, and I got caught in traffic. So I’m sitting in traffic and I reached over and grabbed the book ,and I was just flipping it open, just how a library book will sometimes open to a spot. And I saw vitamin E jump out at me. Eleanor Gehrig used to go into Central Park every day to pick greens that were high in vitamin E because it was thought that vitamin E might be helpful. At that moment, I got something that I call ALS rage. We were doing the same thing that Lou and Eleanor Gehrig were doing in 1939. And it just seemed nuts to me.

It’s like, how far have we come? Not far. I had liquid centrum instead of picking greens out of Central Park. We were doing the same stupid things. So, that was kind of what set off a switch in me.

Alexis Pedrick: Even though ALS was discovered more than 150 years ago, we still don’t know what causes it. Just 10 percent of ALS patients have a genetic predisposition to it. The remaining 90 percent of cases have what’s known as sporadic ALS. There’s no cure, and there aren’t any good treatments. While there are technically six drugs that have been approved by the FDA, none of them have dramatic results. At best, they dampen symptoms and slow the progression of the disease by just a few months.

This is Lisa John, an ALS patient from North Carolina.

Lisa John: There aren’t a lot of treatments out there for ALS. And the treatments that they do have in place, I tried those. You really don’t care to live after that. It takes what life you have left.

Alexis Pedrick: It’s easy to see that it’s got some cards stacked against it. It’s a rare disease, for one. At any one time, only 30,000 people in the U.S. have ALS, compared to almost 7 million people who have Alzheimer’s. So there’s not a lot of money for ALS research. On top of that, it’s a disease of the brain, which is notoriously our most mysterious organ. In recent years, more money has poured in, and new drugs have emerged.

But here’s the problem. When you get an ALS diagnosis, a ticking clock starts, and you don’t have a lot of time. Before a pharmaceutical company can even put a drug on the market, it has to be approved by the FDA. They have to provide evidence that the drug works, and this process can take years, even decades, which is time ALS patients don’t have.

ALS has created an impassioned and determined group of people, patients and their loved ones, who are desperate for an effective remedy now.

Cathy Collet: One day mom asked me to help her button her blouse. So I helped her button her blouse. She never asked me that before. And she, she said, you know what the worst part is? And I said, no, I don’t know what the worst part is. And she said, the day I’m not able to do something, I know that I’ll never do it again. She knew that she was never going to button her own blouse again. It’s cruel and it’s hard. And, and so your, your ideas of what you need to advocate for and what you need to do to help my person who’s dying before my very eyes, that can be a strong motivator. But it also can, it can blind you to some things that can be kind of pennywise and pound foolish.

Alexis Pedrick: From the Science History Institute, I’m Alexis Pedrick, and this is Distillations,

Chapter One. How One Drug Ignited the ALS Community.

The story of one ALS drug called AMX0035, or AMX for short, illustrates the incompatible timelines between ALS patients and the FDA drug approval process. This is what happened. In 2013, Josh Cohen and his fraternity brother, Justin Klee, were undergrads at Brown University. In addition to being traditional college students, they were also developing a drug for Alzheimer’s.

This is Michael Abrams, a senior health researcher for Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy organization.

Michael Abrams: It’s a couple of young men who now are pharmaceutical moguls, and they like went to school together as undergraduates and took some interest in the neurobiology of these two agents as maybe reducing the cell death that might underpin this and other, you know, degenerative diseases.

Alexis Pedrick: They started their pharmaceutical company, Amylyx, while they were still at Brown, and they were meeting with Alzheimer’s scientists when they ran into Merit Cudkowicz, the chair of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Merit Cudkowicz: I met them, and I was excited about it because I’d actually studied one of the two components, the sodium phenylbutyrate.

We had done a trial with the VA of that drug and ALS, and there was good science for that, and I liked the idea of a combination.

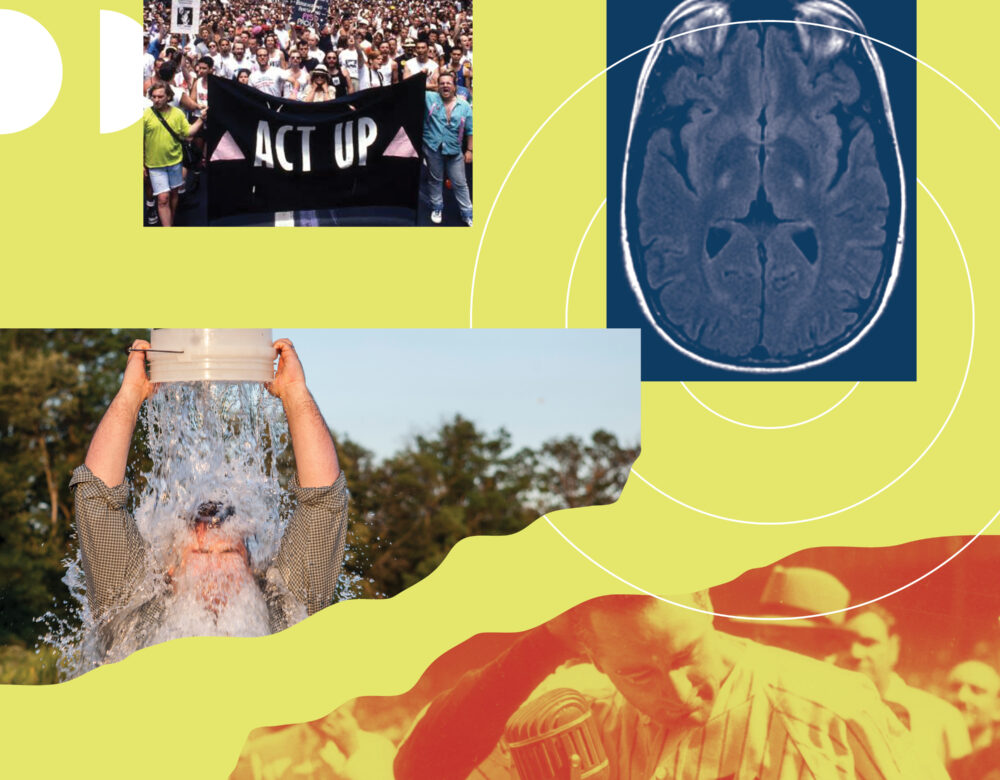

Alexis Pedrick: Merit Cudkowicz thought that it had potential as an ALS drug, and she convinced Josh and Justin to switch from Alzheimer’s to ALS. She made some introductions that helped them get two million dollars from the ALS Association, which came directly from the Ice Bucket Challenge, that 2014 viral sensation that made the world aware of ALS.

Ice Bucket Challenge Archive: The only thing colder than this bucket full of ice cubes is doing nothing to help fight ALS.

Merit Cudkowicz: Before the Ice Bucket Challenge there were, you know, a couple hundred people working on ALS and lots of good ideas but no funding and all of a sudden the Ice Bucket Challenge not only raised a lot of money for research but also a lot of awareness, and it ended up bringing in lots of new people into the field from all over the world, scientists, patient advocates, you know, pharma.

And I think it was a big catalyst at the right time.

Alexis Pedrick: Cohen and Klee were ready to move on to drug trials, but that part was not so easy. The pool of ALS patients is small. Remember, there are only 30,000 people living with it at any one moment, so it’s a challenge to get volunteers for the trials. But ALS patients have a reputation for being generous in this way.

Merit Cudkowicz: I always remember one of the first people I took care of who was part of my first trial, and I was so disappointed when the trial was negative, and she wrote me a note and said, Thank you for letting me be part of the study. I’m sorry it didn’t work, but I’m ready to sign up for your next one. And I, I keep that, uh, letter with me because we have to be resilient.

Alexis Pedrick: Thanks to Cudkowicz, Josh and Justin had a pool of patients they could tap into. They did a trial with 137 patients for six months. The results were published in 2020, and it showed that patients decline slowed by 10 months.

Merit Cudkowicz: It was very exciting. And I mean it, really. We’ve done a lot of clinical trials and, and, um, not, not had that many successes. So it was, it was wonderful to see, you know, it was just a relatively small study.

Alexis Pedrick: Like we said before, a pharmaceutical company puts a drug on the market. It has to be approved by the FDA. They have to provide evidence that the drug works in the form of clinical trials. The first phase involves enrolling 20 to 100 volunteers with the disease. Some get a placebo, while others get the drug. Phase 2 trials enrolls a few hundred people, and Phase 3 enrolls thousands. If the data shows the drug works, then it goes before an advisory panel of experts, who make a recommendation to the FDA for approval. And once approved, the pharmaceutical company can market the drug and price it as they see fit.

Remember, this process can take years and sometimes decades. After the news of that first AMX trial hit, ALS patients wanted to take the drug immediately. They didn’t have years to wait for the normal drug approval process. They’d be dead by then. So they started speaking up and the makers of AMX asked the FDA to consider the drug under what’s called the “Accelerated Approval Pathway.” This is allowed as long as the evidence is good, but this fast-track pathway raised red flags for Michael Abrams of Public Citizen.

Michael Abrams: Because the evidence requirements are a lower standard than they otherwise would be. So I think the average American person and especially like physicians think, Oh, every drug that’s on the market goes through two solid randomized control trials that are independent and both show an effect.

Alexis Pedrick: The accelerated approval meeting for AMX was in March of 2022. The drug went before an advisory committee of experts who considered its merits.

Michael Abrams: And the evidence just wasn’t there. We testified. against it. The clinical benefits being demonstrated were very limited. The sample size is very limited. And the committee at that point I believe voted against it.

Alexis Pedrick: ALS patients and advocates testified in favor of approving the drug, but the panel voted 6 to 4 against it. Which was surprisingly close because the FDA analysis said that quote, “the improvement on patients may not be sufficiently persuasive for approval.”

Michael Abrams: Typically, if there’s a failed advisory committee vote, either the drug will die on the vine, if you will, or you’ll see a substantial reworking and a new trial. In this case, what happened was. The manufacturer and the FDA worked together and then just a few months later, like five months later, came back with an open label extension trial.

Alexis Pedrick: In other words, Amylyx got a second chance to get their drug approved without a new trial. If that sounds unusual, that’s because it is. Something remarkable had happened after the drug was rejected. The ALS community rallied behind it and got the FDA to reconsider it. In the years after the Ice Bucket Challenge, the ALS advocacy community had become a strong, organized force.

Chapter Two. The ALS Advocates.

In May of 2024, a group of ALS advocates gathered on the National Mall in Washington. Organizers had placed 6,000 blue flags in the ground in front of the Washington Monument, and they represented the number of people who are diagnosed with ALS every year. Each one listed someone’s name: Ann Harper, diagnosed at age 62, died at 63. Ana Sylvia, diagnosed at age 58.

Sarah Koulouras: A century ago, the lifespan for someone diagnosed with ALS was two to five years. A hundred years later, it’s still the same diagnosis. And so we’re trying, sorry, we’re all trying to come together and change that for generations to come.

Alexis Pedrick: A man named Paul Seifert, who has ALS and uses a wheelchair and a ventilator, took the stage.

Paul Seifert: This is a tough disease, and Congress ain’t a light touch. So if you want to get money to kill this disease, we gotta get tougher. There was a bridge collapse on the Patapsco River. A great big ship ran into it, knocked the whole thing into the water. Killed six people. People were saying, it’ll be months. Months. Years, maybe. Before they get it cleared. Two months later. Cleared. How did they do that? They threw a bunch of money at it. Okay, that’s what happens. We get a billion dollars a year and funding for ALS research. This disease is over, over. And no one will ever have to deal with it again.

Alexis Pedrick: A woman named Candace Donovan spoke about what it’s like to live with the disease.

Candace Donovan: Our bodies become stone like, which is unable to make us move, unable to hug our loved ones. Breathing is like suffocating. Our voices and the voice that’s speaking to you today, we become muted and our laughter becomes muted. Behind all of our physical setbacks that we feel, our minds are never touched. Our, our minds stay exactly the same. We know everything that’s going on. We understand everything that’s going on. And what happens is we feel and see the overwhelming fear of our family and our friends. And we lose most of our friends because our friends don’t want to see us change. And that’s, what’s hard for us. Because we know we’re changing. We feel we’re changing.

Alexis Pedrick: The event was organized by a patient led advocacy group called I AM ALS. The founder of the group is a man named Brian Wallach. He was once a lawyer on the White House counsel team in the Obama administration, and he was also a federal criminal prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Chicago before he was diagnosed with ALS in 2017. Since then, he’s used his political connections to make gains for the ALS movement. Here he is speaking through an interpreter.

Brian Wallach: The role of the community is everything. And everyone has a voice.

Alexis Pedrick: I AM ALS has had some major successes. Between 2019 and 2021, they lobbied Congress to increase spending on ALS research from 10 million to 80 million a year. They also convinced Congress to change the law so that people with ALS can get immediate Social Security benefits instead of having to wait five months, which is too long for someone with ALS.

The group has been praised by patients and their caregivers, even Barack Obama has endorsed them. But there’s one thing they’ve been criticized for, pressuring the FDA to pass unproven drugs. Drugs like AMX. Brian Wallach testified in favor of AMX in front of an expert panel through an interpreter.

Brian Wallach: My name…this denial is wrong. It makes this an academic question rather than one that impacts real people and families whose lives are in your hands. I don’t need you to protect me from myself, with all due respect that antiquated paternalism is misplaced. I have studied this drug for four years and lived with ALS for five. I know as much. It’s not more about AMX0035 than many of you do. And I am not an anomaly. ALS patients do our research. We don’t want to try just anything. But we absolutely want to try a safe and effective drug like AMX0035. Instead of thinking you are protecting me, I want you to recommend approval so that I have the chance to live.

Alexis Pedrick: Brian Wallach and other ALS patients are not the first people to be afflicted by a fatal, fast moving, and incurable disease, who then decide to take on the FDA. In fact, a whole movement had already laid the groundwork decades earlier, and Brian drew inspiration and a roadmap from it.

Chapter Three. The AIDS Activism Roadmap.

News Archive: The headquarters of the Food and Drug Administration in Rockville was virtually shut down today. As demonstrators demanded the release of new drugs for AIDS victims.

Alexis Pedrick: In 1988, AIDS activists protested outside the FDA, demanding faster access to AIDS drugs in development. This is a clip from the 2012 documentary How to Survive a Plague.

How to Survive a Plague: AZT is not enough. Give us all the other stuff. We are not asking the FDA to release dangerous drugs without safety or efficacy. We are simply asking the FDA to do it quicker.

Alexis Pedrick: There was only one FDA approved AIDS drug at the time, AZT. In the best cases, it slowed the progression of the disease minimally, but it also had severe side effects.

How to Survive a Plague: So far, you’ve got AZT. Why would- Which I can’t take because it’s far too toxic and over half the people that have HIV says there is nothing else that is worth anything.

Alexis Pedrick: Drug trials in the pipeline were still years away from being available. And like ALS patients today, 1980s did not have time to wait for them. The life expectancy after diagnosis was one to two years.

How to Survive a Plague: The problem is, is that the FDA is using the same process to test a nasal spray as it is to test AIDS drugs. And it’s a seven to 10 year process.

Alexis Pedrick: So AIDS activists, most notably the group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP, took matters into their own hands.

Lewis Grossman: And I describe this as the first great movement for freedom of therapeutic choice within orthodox medicine.

Alexis Pedrick: This is Lewis Grossman, a law professor at American University, and the author of the book Choose Your Medicine.

Lewis Grossman: Because the AIDS activists weren’t campaigning for access to herbs or homeopathic medicines. They were campaigning for access to products. of the modern pharmaceutical industry and the modern pharmaceutical research complex.

Alexis Pedrick: They believed in the science, they just wanted it to move faster. And that 1988 FDA protest was part of their strategy.

News Archive: Their goal is to shut down the FDA for the day, to keep workers from getting in, and to grab the media spotlight.

Lewis Grossman: And it was very effective with the media and with changing attitudes. And that crowd included the entire range of AIDS activists, from the people who never got beyond the level of street protest to those who would ultimately become very, very sophisticated medical thinkers and medical regulatory thinkers in their own right. And what was striking about them as models for future patient advocacy is how they became unbelievably educated in the science of AIDS and the science of AIDS treatment so that they could argue with regulators in sophisticated terms. Ultimately work their way into the system working with Tony Fauci and other leading federal bureaucrats.

Alexis Pedrick: AIDS activists were the ones behind “accelerated approval.”

Lewis Grossman: That was invented during the AIDS movement and was actually invented, some might say, by AIDS activists themselves.

Alexis Pedrick: The idea was to base approval on promising evidence rather than certain evidence when people have severe diseases. The AIDS activists made it clear that people in their position wanted the freedom to take drugs that were less than perfect. And eventually, this activism helped bring about the actual effect of drugs for HIV.

Lewis Grossman: Because we all live in lives of uncertainty, and ultimately, whether FDA approves a drug or not, I tell my students this all the time, the question of safety is a scientific question. The question of efficacy is a scientific question. But the question of whether or not the evidence of efficacy sufficiently outweighs the safety concerns to allow a drug on the market is a policy decision. It is inevitably a policy decision. And what the AIDS activists did is push FDA to adjust its implementation of that policy and to be less protective of consumers and the public with respect to, to drugs that maybe haven’t been fully studied and more protective of the choices of people to decide for themselves.

Alexis Pedrick: And this activism helped change the way drugs were approved.

Lewis Grossman: It used to be that almost no drugs were approved unless they had successfully completed two large, adequate and well controlled clinical trials. Now many drugs are getting onto the market with only one clinical trial or one well controlled clinical trial.

Alexis Pedrick: AIDS activists achieved something else that defined ALS activism. They successfully made patient testimony part of the FDA’s drug approval process. The meetings used to be exclusively experts, mathematicians and scientists, but AIDS activists got themselves a seat at the table, and now ALS patients have one too, and their testimony is now part of the process.

Lewis Grossman: They used to be the driest, most technical events that you could possibly imagine. Today, especially for drugs for certain conditions, they are public forums for activism brought right to FDA’s doorstep by people testifying in the open portion of these advisory committee meetings.

Alexis Pedrick: And in 2022, it was ALS advocates who were on the FDA’s doorstep, demanding the approval of AMX.

Chapter Four. Showdown at the FDA.

After AMX was rejected for accelerated approval in March 2022, Merit Cudkowicz submitted a criticism of the decision.

Merit Cudkowicz: I wrote an editorial with a colleague of mine about this idea of, um, single study approval, you know, conditional on replication, uh, which was really a new idea in ALS, but a very old idea in, in, with the FDA for other life-threatening illnesses. And I, I You know, that’s my personal opinion. It’s not, you know, not MGH and not Neil’s, that we should have that pathway for patients living with ALS.

Alexis Pedrick: The argument that Cudkowicz made boils down to this. The drug only had one small study. But it did show that it worked a little bit. Amylyx, the drug company behind it, was already doing a confirmation trial with the code name Phoenix. Now that trial would take years, but in the meantime, the FDA should approve the drug. The FDA already does this with cancer drugs, so why not do it for ALS too?

Merit Cudkowicz: Of course, if the study repeats positive, everyone thinks, you did the right thing, you just gave a drug that works, you know, two or three years early to people with a life threatening illness. If it doesn’t work, then it’s a flip. You just gave a drug that doesn’t work to people. Um, but I, I believe patients should have that choice with, with this serious type of illness.

Alexis Pedrick: The FDA Advisory Committee met for a second time in September 2022 to reconsider AMX0035, which, remember, was concerning for Michael Abrams at Public Citizen. Of particular concern, was the man leading the meeting. Billy Dunn was the director of the FDA Office of Neuroscience.

Michael Abrams: He especially caught our attention because of his, what we thought was very inappropriate role, shepherding aducanumab.

Alexis Pedrick: In 2021, Billy Dunn was a key player in the controversial decision to approve an unproven Alzheimer’s drug, which has since been taken off the market. So Michael was worried when he attended that second AMX meeting in September of 2022, and Billy Dunn was leading the meeting.

Michael Abrams: At some point, Billy Dunn Takes the dais and says, um, you know, describes the FDA’s position, thanks people and so forth, and then says something to the effect of-

Billy Dunn Archive: And I call on the company’s co CEOs for the committee, whether the company would voluntarily withdraw the product from marketing, if the Phoenix study does not succeed, should their current application ultimately be approved.

Alexis Pedrick: In other words, he was asking the CEOs of Amylyx to remove the drug from market if it failed the next trial. He wasn’t telling them to do it, he was asking them to do it. He was banking on the goodwill of the company’s CEOs.

Michael Abrams: Then, one of the CEOs, these young men that I described, said, Yes, we promise, we’ll do the right thing if it fails clinical trials. And that was one of the, unique things about this drug, the clinical trial called the Phoenix trial had already begun.

Justin Klee (Amylyx) Archive: To be clear, if Phoenix is not successful, we will do what is right for patients, which includes voluntarily removing the product from the market.

Alexis Pedrick: The problem is, there’s no way to enforce this. There isn’t even an apparatus to make sure that there are follow up trials. Technically, a company can just do it. Take it as a win. They got a drug to market without having to do extra work. And Michael has seen this happen. In one instance, a company got accelerated approval for three drugs for muscular dystrophy but failed to complete follow up trials.

Michael Abrams: Part of the reason we opposed it is because we didn’t trust them, nor did the FDA, because of the fact that they had gotten accelerated approval on Eteplirsen a number of years ago, and haven’t done their post marketing studies that they said they would, and nobody really knows to this day whether it worked.

So, the, you know, the obvious concern that one has is that these manufacturers know that if they can just get it through and get that approval, even if it’s accelerated, they can just kick the can down the road and make a lot of money, over a lot of period of time for a drug that maybe is no better than placebo, and on top of it, might even cause harm, but the signal is so vague that they just go years and years and hobble along and make patients and insurers pay. I mean, that’s a terrible outcome.

Alexis Pedrick: Because of this, Michael Abrams spoke against the approval of AMX at the FDA hearing in September.

Michael Abrams at FDA Archive: The FDA stated it, quote, does not find these data sufficiently independent or persuasive. We recommend that the committee vote no on the question before you today and that the FDA not approve this medication for ALS at this time.

Alexis Pedrick: Abram’s position was in the minority. It was eclipsed by the powerful and desperate testimonies of ALS patients and advocates who made their exceptional situations clear. People like Scott Kauffman, whose son was diagnosed when he was 27 years old.

Scott Kauffman Archive: And as a parent, I can assure you that it’s the worst possible diagnosis you can hear about your child. I strongly urge you to recognize the great unmet need in this space, and the willingness of the FDA and Amylyx to be flexible. People living with ALS don’t have time to spare. Please make the right decision and determine there is sufficient evidence about the safety and efficacy of AMX0035 to make it a treatment option for people living with ALS today.

Alexis Pedrick: Steve Kowalski is 58 years old and was diagnosed in 2017.

Steve Kowalski Archive: Any additional time with loved ones or maintaining physical function has measurable value on the quality of life in self-independence. More time and function is valuable to every human being. We cannot wait years for the Phoenix trial when people with ALS are looking at a treatment that is safe and effective today. If we wait, many who are living with ALS will no longer be with us.

Alexis Pedrick: Krista Thompson’s husband, Olin, passed away from ALS and was part of the AMX clinical trials.

Krista Thompson Archive: What does 10 more months of function mean to our family? Well, it means that Olin was able to go out to dinner a week before he died. And enjoying ice, an ice cream with, with his sons in the past 10 months, Olin got to see our oldest finishes first year of college. We got more moments and more time to be a family of five. Please do not rob other families of those 10 months because when you only have memories left 10 more months of making memories means everything.

Alexis Pedrick: It’s important to recognize that not everyone would get those 10 extra months from the drug. That was the whole problem. That was the part that still wasn’t proven. There were only two people out of 20 who opposed the drug, and Michael was one of them. The panel voted to approve it. And he worries they were so moved by the testimonies that they approved an unproven drug.

Michael Abrams: It should give some weight, but never the same weight as, you know, a sort of dispassionate, you know, full view of the data. I mean, that’s the whole beauty of the of the experimental method and of science is that it’s, you know, testable, retestable, confirmable that you actually get information that overcomes basic biases that we hear.

Alexis Pedrick: But ALS advocates were thrilled with the decision.

Merit Cudkowicz: I thought that was a big forward movement for the ALS field. A bit like the ice bucket campaign, you know, the awareness and funds and here was a path forward that would be faster for getting drugs to people with this illness. And that it would attract more companies and more investment in the field.

Alexis Pedrick: Finally, after so much time and so many failures, it seems like ALS had scored a much-needed victory. But there would be new roadblocks ahead, starting with the pricing of the drug. The company branded AMX0035 as Relyvrio and priced it at $158,000 a year. Here’s Cathy Collet again.

Cathy Collet: I think their price was outrageous.

Alexis Pedrick: After her mother died in 1997, just one year after she was diagnosed, Cathy became an ALS advocate. She followed the AMX saga closely.

Cathy Collet: The pricing, I thought, was absurd, especially for a drug that was, like, not, not a slam dunk. They were getting what they could get.

Alexis Pedrick: One of the things that Public Citizen does is assign a price value for a drug once it’s on the market.

Michael Abrams: Amylyx had a monopoly. They can charge whatever they want for some people, okay? That will certainly pose a problem for access. There are lots of efforts then to get to a fair price. Typically, calculations are done on some measures, you know, how much mortality, morbidity is saved from the drug. In the case of this Amylyx drug, that was the problem. It was zero. The drug, we said originally was worth zero, okay? That doesn’t mean the willingness to pay for somebody who has ALS is zero because they’re desperate.

Alexis Pedrick: And Amylyx needed to make their money back. Remember, ALS is rare. The potential market is just. 30,000 people in the U. S., so they have to price it high to recoup their costs. Cathy Collet supported Amylyx when it was trying to get approval, but she was critical of the pricing, and she’s an influential advocate in the ALS community, so what she says matters.

Cathy Collet: I will be very honest with you after I made public comments about thinking the pricing was outrageous. The CEOs of Amylyx wanted to talk to me and I thought, Oh boy. So we had a call and the first thing I asked them was, is this an intervention? And they laughed. It turned out to be a cordial call, not productive because they told me the things that I expected to hear about the value of drugs compared with the cost of healthcare and all that.

And I understand that, but I still think their price was outrageous because they weren’t slam dunk trials. And. I think we as advocates need to sit down with sponsors and say, Hey, charging as if this were a slam dunk product is not good value based pricing. It’s not right.

Alexis Pedrick: You might be asking yourself, what’s the problem with giving desperate patients something, even if it’s not perfect? As long as it’s not dangerous?

Chapter Five. What’s the Harm?

The immediate harm is financial. With such a high price point, only the most wealthy patients could afford this drug’s $158,000 price tag. And what’s more is that if an insurance company or Medicaid agree to cover it for patients, then the cost gets passed down to the public via insurance premium increases. But there’s another potential harm that’s less obvious.

In the 1980s, AIDS activists were struggling against what they saw as a paternalistic FDA. The FDA wasn’t used to hearing from patients themselves, and didn’t take them seriously at first. Things have changed since then, but has there been an overcorrection? Is the FDA now giving too much power to patients? And are they lowering their standards of evidence in the process?

Cathy Collet: Now, I think they’re trying to be flexible, reasonably flexible, and, and I think there’s room for that, but I think you have to draw a line. If you are flexible to the point that you become Gumby and there are no standards, then I say, why are we even doing clinical trials? If you’re not going to pay attention to them, why are we even doing them?

Alexis Pedrick: Some AIDS activists have become skeptical of accelerated approval programs for drugs. This is a clip from the documentary How to Survive a Plague.

How to Survive A Plague: A split has developed between those who want rapid approval based on early indicators of success and the Treatment Action Group, or TAG. TAG has asked the FDA to reconsider the accelerated approval process. We told the FDA, no, the company’s asked you to approve that drug too soon. They need a little bit more data first.

Alexis Pedrick: The activism done by ALS advocates is incredible. They’ve gotten bipartisan bills passed through Congress, raised hundreds of millions of dollars in private donations, and have gotten Congress to allocate tens of millions more. But, perhaps they need to start pulling other levers too.

Cathy Collet: We have those tools now that they opened up for us, but you’ll also find AIDS activists who will tell you that. The FDA is not, probably not your problem at this point.

Alexis Pedrick: There’s one key difference between the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and ALS today. The science moved much more quickly from the discovery of the virus, HIV, to the discovery of the vaccine. to a diagnostic test, to effective drugs. On the other hand, we still don’t understand what causes ALS. Cathy Collet says this is why more basic research is needed, and that doesn’t come from the FDA.

Cathy Collet: FDA is not your problem. Your problem is to get NIH doing more. You need better research into a poorly understood disease. Drug companies want to tell you, well, approval is the only tool, you know, because it’s like, that’s the only way they’re going to get the product to market and be able to make some money on it. And clinical research is dreadfully expensive. I understand that. But at the same time, I’m not sure that we want to lower the bar on approval, in order to generate all of these little cash cows for them, because then what do we end up with? We end up with a bunch of not great products and are the incentives there for the drug companies to do the really difficult things and the really novel science

Alexis Pedrick: The AIDS movement was more grassroots, but now advocacy has become more professionalized. Drug companies are telling activists that the only avenue they have is FDA approval, and they enlist their help to get their drugs approved.

Cathy Collet: When you’re dying, it compromises so much, your judgment gets clouded. It’s just real. I mean, you’re kind of living in this horrible fog and then you want your loved one to have access to stuff. And I think they should have access to things, but I don’t think they should be approved by the FDA so that the companies are, are cranking them out like they have efficacy. I think if you get access to things, where the efficacy hasn’t been shown, I think that’s great, but you need to know it, and it needs to come from a company, and they shouldn’t be profiting off of it.

Alexis Pedrick: Lewis Grossman says that just because they’re desperate doesn’t mean they don’t have agency of their own.

Lewis Grossman: I’m confronting a desperate situation, and it might be effective, and I should get to make that choice. I mean, I think that that’s the basic theme behind their testimony. And misguided or not, I refuse to think of them as just dupes when they’re making that testimony.

Now of course, then the question turns into, okay, you can have access to it, then the question turns to, who’s going to pay for that access? And that’s where our society, even the most libertarian aspects of our society don’t really have any good answers.

Alexis Pedrick: On April 4th, 2024, the makers of AMX pulled the drug off the market after their confirmation trial showed it didn’t work. In its short time on the market, Amylyx made $49 million in profits.

Cathy Collet: I’m grateful for the company that they let the data speak and they were not playing games. I mean, they could have done all kinds of things to muddy the waters or make it look like it really worked, even though the data don’t say it works. But they didn’t. They, as I call them, good corporate citizens, and I appreciate them.

Alexis Pedrick: It was hard news for Merit Cudkowicz.

Merit Cudkowicz: It was really disappointing, I mean, for in so many ways. You know, for our patients, uh, first and then also for the, the field, you know, we had so much hope on that, but on the other hand, I wasn’t completely surprised. I mean, we know that these, these small studies can sometimes not be correct. I still think it was the right path to do.

Alexis Pedrick: Despite the setback, she says she has hope that there will one day be a cure for ALS. There’s never been more money, more researchers working on this problem, and there have been some breakthroughs.

Cathy Collet: Hope is good. You need hope when you’re dealing with ALS. Hope is wonderful. That it has to be anchored in reality, in some way. And I think it’s wrong. I call it holding hope hostage. You, you shouldn’t hold hope hostage and you shouldn’t say, well, even if this doesn’t work, Mom’s vitamin E probably wasn’t doing a thing, didn’t hurt. I mean, it was like cheap enough at Walgreens and it certainly wasn’t hurting her. So, fine. But, when you talk about FDA approvals, when the FDA’s job is to say this is safe and effective, then I think we have to pay attention to the effective part.

Alexis Pedrick: Distillations is produced by the Science History Institute. Our executive producer is Mariel Carr. Our producer is Rigoberto Hernandez, and our associate producer is Sarah Kaplan. This episode was reported by Rigoberto Hernandez and mixed by Jonathan Pfeffer, who also composed the theme music. You can find all our podcasts as well as videos and articles at sciencehistory.org/stories. And you can follow the Science History Institute on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for news about our podcast and everything else going on in our free museum and library.

For Distillations, I’m Alexis Pedrick. Thanks for listening.