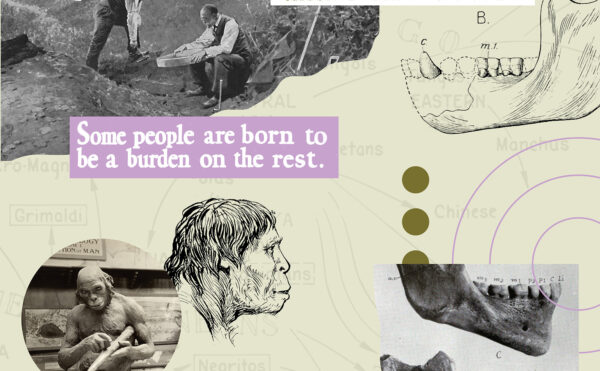

Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race

Race is a myth. Racism is a reality.

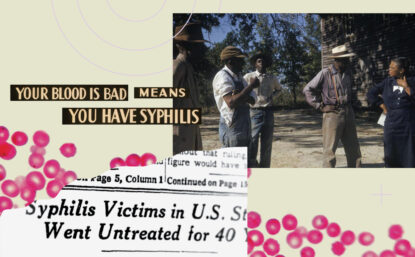

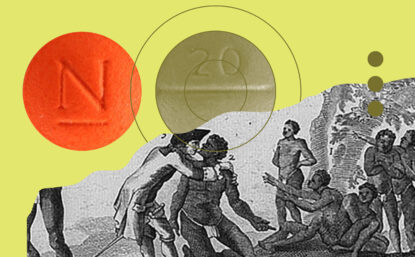

Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race is a podcast and magazine project that explores the historical roots and persistent legacies of racism in American science and medicine. Published through Distillations, the Science History Institute’s highly acclaimed digital content platform, the project examines the scientific origins of support for racist theories, practices, and policies.

The Institute hosted a number of free public events highlighting the stories told through the project.

Questions about Innate? Email us at podcast@sciencehistory.org.

PODCASTS

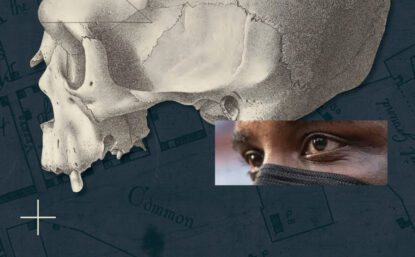

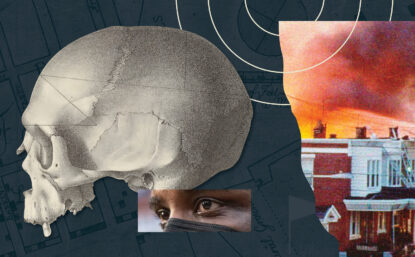

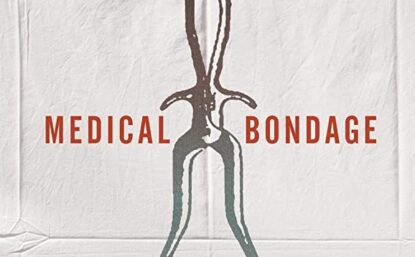

The centerpiece of Innate is a series of 10 Distillations podcast episodes that dropped weekly starting on Tuesday, February 7, 2023. The season explores stories such as how a 1793 yellow fever outbreak proved a racial myth wrong, how a collection of skulls forced a museum to confront its racist past, and how a group of medical students has been trying to dismantle the practice of race correction.

ARTICLES

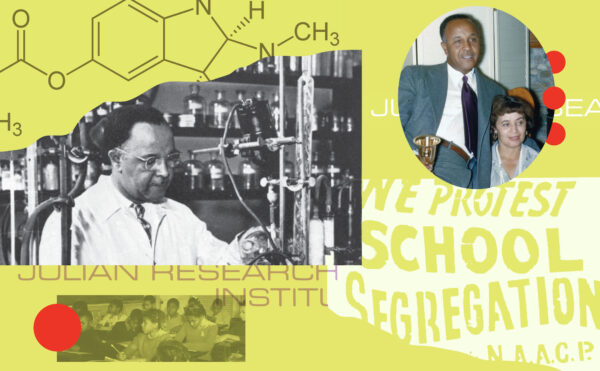

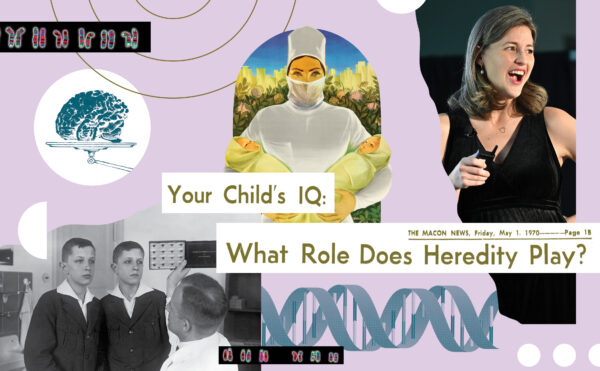

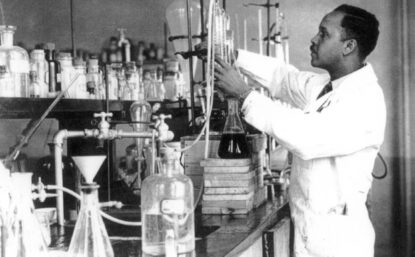

Distillations magazine examines the costs of racism in the discipline of science. Features tell the stories of a chemical genius stymied by racism, the schism that has hamstrung behavioral genetics since the field began, and an archaeological hoax and its supporting role in race science and eugenics.

ONLINE COURSE

The Science History Institute teamed up with online learning platform Roundtable for a free, five-session course examining the roots of racism in American science and medicine.

What is the truth behind the concept of race, an invention so pervasive many consider it fact?

Join the team behind the Science History Institute’s critically acclaimed Distillations podcast in separating fact from myth regarding what anthropological research can and cannot tell us about a culture.

PUBLIC PROGRAMS

From a First Friday kick-off event, to virtual lectures with historians of race and medicine, to an on-site tour of the first quarantine station in the United States, take a closer look at Innate through these engaging events.

EDITORIALS

What Did We Learn?

It’s baked in.

A little over a year ago, we walked into the Science History Institute library with a question: where did racism in science begin? We thought we’d be able to neatly separate “good,” non-racist science from anything “bad,” racist, and unscientific. But when we opened some of the oldest texts in our collection, we found something we didn’t expect. Racism was already there in those old pages, and scientific questions, practices, and conclusions have been formed around racist perspectives over the centuries.

It feels strange to write this because we love science. But as historians and storytellers looking at its history, our job is to ask questions about its successes and failures. We do that because science is not a stand-alone entity. It’s subject to the same forces that shape our society—culture, power, politics and, yes, even bias.

Producing the Innate podcast season has been a journey. We first got the idea back in 2018. At that time, we thought, perhaps naively, that it might be a two-part podcast episode. Time passed, and every question we asked led to more questions. The pandemic came. We watched the murder of George Floyd with our hearts in our throats. We wrung our hands and worried about the world and how we could help make it a more just place.

We still had our pile of questions.

In October 2021, the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded us a grant and our search shifted into high gear. We collected hundreds of hours of tape, pages of research notes, and piles of books that blanketed our dining room tables. We tweaked scripts, brainstormed article ideas, and started a reading group with our colleagues. We laughed and cried and sat in Zoom meetings shaking our heads. Our Slack channel filled up with news links, story tips, and a list of sources we hoped might return our calls.

So, what did we learn?

For one, innate racial difference is a myth. It’s not scientific. Despite centuries of effort, there is no proof that skin color makes us biologically different. No lab is on the verge of isolating genes that make one group of people superior to another. It’s made up. A lie. Always was. Propped up in many cases by the same institutions that told us truths about the stars in the sky and the air we breathe. Why? Because science lends credibility to claims about the world and people want to believe that the scientists’ statements can be trusted.

We also learned about ourselves and how we’ve contributed to bias in the history of science—a quiet type of racism. You don’t have to broadcast race science to have contributed to narratives in the history of science that marginalize women and people of color. As a museum and library, we do it every time we prioritize primarily white, mostly male stories of science. We do it when we choose to venerate a figure of history rather than investigate all their actions. We teach people which questions about science are worth asking. And if we never ask about racism, we are effectively telling them it’s not important.

So, we have work to do. Lots of it. But first, we have to unlearn the myth. And we hope you’ll join us and legions of scholars, researchers, and everyday people pushing back against this harmful belief.

Because there is hope.

Throughout this hard and sometimes heartbreaking project, we learned that too.

Signed,

The Distillations Team

In 2022 the Science History Institute marked its 40th year as a library and museum dedicated to supporting research and fostering audience interest in the histories of chemistry, engineering, and the life sciences. Over these last 40 years, we have built a reputation for “telling the stories behind the science“ and for drawing on our collections and our researchers’ expertise in these fields to craft engaging historical accounts of scientific phenomena and the people responsible for them—accounts that reveal and interpret the origins of scientific developments and technologies that our audiences encounter in their daily lives.

These narratives have demonstrated that the agents in scientific enterprises can make discoveries that astound and inspire us, as well as mistakes that confound and even amuse us. But research into our collections also yields stories that outrage us, illuminating theories and practices that, under the guise of science, have flouted accepted scientific methods and ethical standards and, most importantly, done irreparable harm to people.

Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race is a collection of such stories. This project identifies and unpacks moments in the history of science when members of the scientific establishment and their institutions sought to provide “scientific” support for racist perspectives and behaviors. By exposing and contextualizing racist biases in our scientific past, my Institute colleagues have explored how myths of racial difference shaped that past—and have alerted us to the persistence of these myths in contemporary scientific discourse.

Innate is a signal contribution to a growing body of scholarship that reminds us that science does not develop or exist in a cultural vacuum. And as the Institute looks to its future, Innate is emblematic of the wide critical lens and diverse historical perspectives that we will employ as we continue to “tell the stories behind the science” over the next 40 years.

David Allen Cole

President and CEO

Science History Institute

NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES

Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race is made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this project do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.