Louis Fieser and Mary Fieser

Although the Fiesers undertook important chemical research, their real fame came from the books they wrote in the mid-20th century, especially their textbooks.

In recent times textbooks have been central to learning chemistry. From the 1940s through the 1960s Louis and Mary Fieser wrote several successful chemistry textbooks. The books were particularly popular because the Fiesers described real applications of chemistry for medicine and industry.

An International Education

Louis Fieser (1899–1977) hailed from Columbus, Ohio, where his grandfather had once been superintendent of schools. He graduated from Williams College in Massachusetts with a degree in chemistry and a great record as an all-around athlete. He then undertook graduate studies in chemistry at Harvard University and wrote his PhD dissertation under James Bryant Conant. After a traveling scholarship that enabled him to study in Frankfurt, Germany, and Oxford, England, in 1924 Fieser took up an appointment as an assistant professor at Bryn Mawr College, a school for women located just outside Philadelphia.

Encountering Discrimination against Women in the Sciences

Mary Peters Fieser (1909–1997) was born in Atchison, Kansas, but when she was still a child, the family relocated to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Her father was an English professor, and her mother owned and managed a bookstore and had taken graduate courses in English. Mary learned her habit of hard work from her grandmother. At a young age she also got into the unusual habit of getting up every morning at 2:00 a.m.

She went on to attend Bryn Mawr College, as did her sister, who eventually became a mathematics professor at the University of New Hampshire. Mary had planned to become a medical doctor but changed her major to chemistry, partly due to the influence of her chemistry professor (and future husband), Louis Fieser.

When she graduated in 1930, she went to Radcliffe College in Massachusetts to earn her master’s degree. She actually took most of her courses at Harvard University and did her research there, but she had to enroll in Radcliffe because Harvard did not admit women students or award them degrees at that time. Louis Fieser had taken a faculty position at Harvard, and Mary did her graduate research in his research group.

While Professor Fieser was open to having women work in his lab, other Harvard faculty were not so progressive. Mary took a lab course under one professor who refused to let her carry out the class lab assignments in his laboratory, making her work unsupervised in the basement of a neighboring building instead. She received her master’s degree in 1932, and she and Louis were married that same year.

Mary decided not to try for a doctorate, reasoning that she would always be able to work in her husband’s lab, whether or not she earned a doctorate. She had already encountered discrimination at Harvard, and in those days many universities and chemical companies would not even consider hiring a female chemist. “I could see I was not going to get along well on my own, [but as Mrs. Fieser] I could do as much chemistry as I wanted” (“Mary Fieser: A Transitional Figure in the History of Women,” Journal of Chemical Education 62: 3 [March 1985], 188).

Studying Molecular Structures

The Fiesers worked in organic chemistry. They synthesized compounds that already existed in nature in order to study the natural materials. Their approach worked like this: if they thought they knew the molecular structure of a natural compound, they would synthesize a molecule with that molecular structure. If their synthetic compound had the same properties as the natural compound, then they knew they were probably right about the molecular structure of the natural compound.

Synthesizing Vitamin K and Other Compounds

The Fiesers worked with steroids leading to the synthesis of cortisone. They also synthesized vitamin K. In addition, the two synthesized derivatives of quinine, a compound used to treat malaria. They were hoping to make a good synthetic drug that could be used to replace quinine since supplies of the drug were short during World War II and many soldiers fighting in the tropics were becoming ill with malaria. But unfortunately none of their compounds turned out to be a useful malaria drug.

Louis’s Wartime Work

During World War II, Louis also led the research team that succeeded in jelling gasoline so that it could better be used as an incendiary material for setting fire to enemy targets.This material, known as napalm because of its original jelling substance (naphthalene and palmitate), was used by the United States in both World War II and the Korean conflict. During the Vietnam War it came under enormous public censure, especially because of images of the hideous burns it inflicted on civilians caught in the conflict. Unlike some of his colleagues who had developed nuclear arms during World War II and later worked to end or at least control their use, Fieser apparently felt no such responsibility for the subsequent use of his innovation, stating, “I have no right to judge the morality of napalm just because I invented it” (Time, January 5, 1968).

Writing Collaborators: Creating Popular Science Texts

The first book that the Fiesers wrote was a college textbook titled Organic Chemistry, published in 1944 before World War II had ended. Louis had initially planned to write the textbook himself. He had asked Mary to help him with the research, but they both soon realized that the job was so big that the two would have to write the book together. The textbook was innovative because it had chapters on real-world applied organic chemistry and its uses, chapters that were mostly written by Mary. Subsequent editions also included brief biographical information for 454 different chemists. And it was the first of their texts to carry a charming illustration of their many cats in its preface. Their household harbored as many as seven cats at a time.

The Fiesers later began two book series, Organic Reactions and Fieser and Fieser’s Reagents for Organic Synthesis. These were written as series because new chemical reactions and new chemical reagents are always being discovered; so new volumes had to be written to keep up with the latest discoveries. The two published their series until Louis’s death in 1977, after which Mary continued the work on her own until 1994.

Life In and Out of the Lab

Mary Fieser spent her career working in her husband’s lab, although she was not officially an employee of Harvard, and she worked without pay. In the 1960s Harvard gave her the title of research associate, but she still did not get paid for her work.

Generations of students recalled the Fiesers fondly. Louis was an engaging and enthusiastic mentor, and they regarded Mary as their quick-witted mother, aunt, or sister, who was always impeccably dressed and groomed.

For the graduate students the sense of belonging did not end with the laboratory. Showing his athletic propensities, Louis often led expeditions to the beach for swimming and canoeing or to the mountains for hiking.

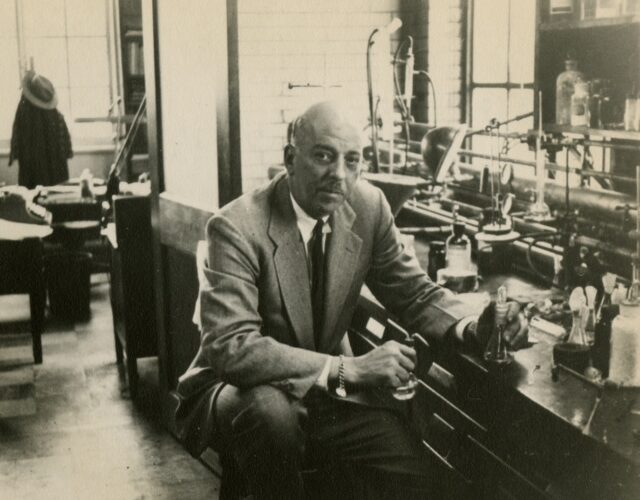

Featured image: Louis Fieser in Harvard University laboratory, December 1950.