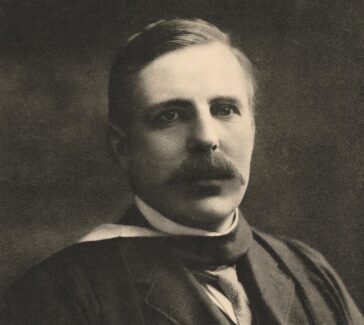

Jane Marcet

‘Conversations on Chemistry,’ written in 1806 by Marcet, was intended for girls, but it also introduced chemistry to boys like Michael Faraday, whose formal education was very limited.

Most well-known chemists are remembered for their research, but some are remembered more as educators. This is particularly true for those who helped change what had once been a profession for white males into one that welcomes diversity in sex, race, and ethnicity. Jane Marcet was instrumental in that transformation.

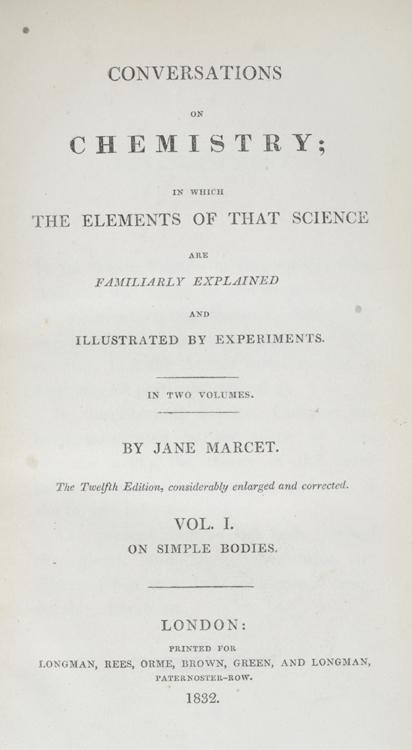

In her 1806 book Conversations on Chemistry, Marcet (1769–1858), an influential science writer, taught chemistry lessons through fictional conversations between a teacher and her two female students. This popular book went through numerous editions and was published in many different languages.

Her Early Life

Marcet was born Jane Haldimand to a wealthy Swiss banking family residing in London. There are no documents from her early life, but education for girls in intellectual families such as hers would have included “natural philosophy” (science) as well as languages and history. In 1799 Jane married Alexander Marcet, another London-based Swiss, who graduated from medical school at the University of Edinburgh in 1797. The couple eventually had three children.

Alexander practiced as a physician in London and became a lecturer on chemistry at Guy’s Hospital in London. The Marcets counted many scientists among their friends, including Mary Somerville, a mathematician and astronomer. Their social circle also included other women writers and scholars. In 1817 Jane’s father died, leaving her a substantial legacy, and her husband gave up medical practice to devote himself full-time to chemistry.

Career as a Writer

Marcet began writing what became best-selling books on science after attending a course of public lectures given by the chemist Humphry Davy. She enjoyed them, she said, but found them confusing until a kind “friend”—almost certainly her husband—explained the concepts to her in a series of “familiar conversations.” Conversations framed in question-and-answer format were considered to be especially appropriate for teaching science to women. (Men, who learned their science at a university, were taught in lecture form.) That was the inspiration for Marcet’s Conversations on Chemistry, published in 1806, followed by Conversations on Political Economy in 1816.

She went on to publish Conversations on Political Economy in 1819 and Conversations on Vegetable Physiology in 1829. All of the books feature discussions between a teacher, Mrs. B., and her two pupils, Emily and Caroline. Emily, the well-behaved older sister, is about 13 years old and ready, according to her teacher, “to acquire a general knowledge of the laws by which the natural world is governed.” Caroline, a few years younger, is less anxious to please and often asks harder questions. But she is, in her sister’s phrase, “an inquisitive little creature,” and her questions, with Mrs. B’s or Emily’s answers, often have the value of furthering the lesson.

Scientific Best Sellers

Marcet’s books were very influential. Her most famous reader was the chemist and physicist Michael Faraday, who read her book while working as a bookbinder’s apprentice. (In those days most books were sold as paperbacks and bindings were added at the purchaser’s discretion). Faraday was inspired by Marcet’s work to go into science instead. But thousands of other people must have read them, too, because her books were best sellers.

Conversations on Chemistry alone went through 16 British editions and at least 16 American ones. It was also translated into French and German. Her works became standard texts at girls’ schools throughout the United States, and individual copies still bear the names of their owners. Marcet’s books express what must have been the philosophy and the experience of their author: that girls, like their brothers, should keep pace with up-to-date natural and human sciences.

Featured image: Portrait of Jane Marcet.

Edgar Fahs Smith Collection, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania