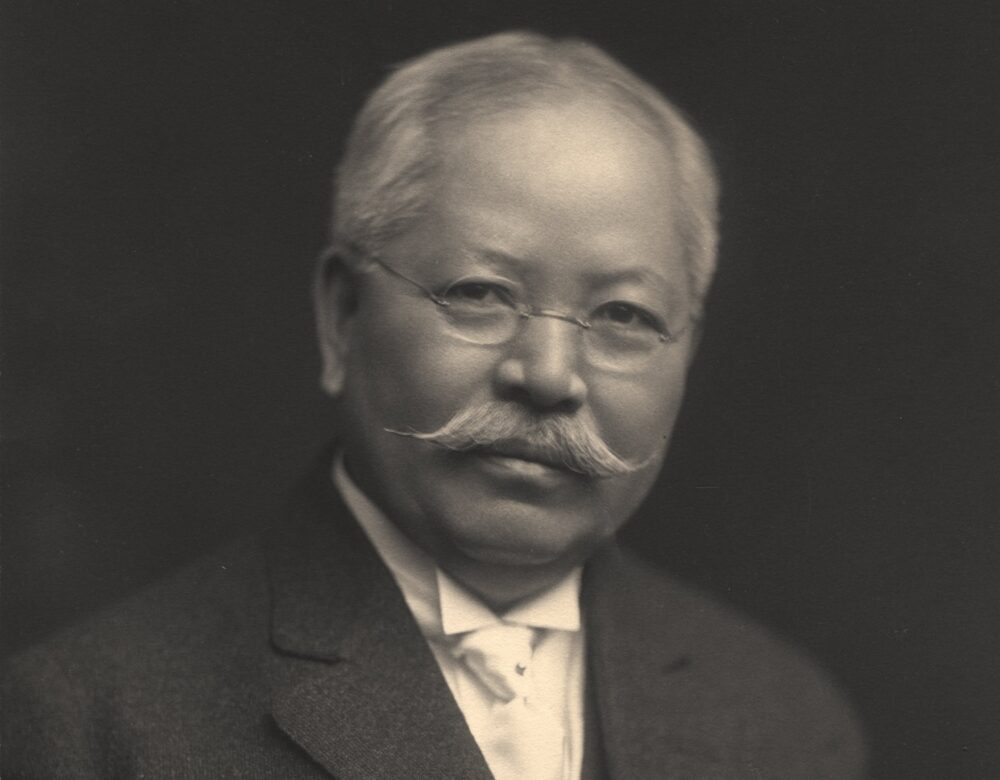

Jokichi Takamine

The Japanese chemist helped isolate the hormone epinephrine and developed new methods of fermentation.

Jōkichi Takamine (1854–1922) built bridges between Japanese and Euro-American science. He helped isolate the hormone epinephrine and developed new methods of fermentation. Successful in business, he turned to philanthropy in later life, facilitating scientific and cultural exchanges between Japan and the United States.

LEARN MORE

Japanese name order puts the family name (Takamine) first and the given name (Jōkichi) second. You may also see ”Jōkichi Takamine” written in some English-language sources. 高峰譲吉 is how his name would appear in Japanese script.

Learning to Speak English with a Dutch Accent

Takamine was born in 1854 in Takaoka, Japan. His family was well-off and highly educated. His father, Seiichi Takamine, was an elite samurai physician who spoke Dutch; his mother’s family owned and operated a sake (rice wine) factory. Under Sakoku, a set of government policies that isolated Japan from 1635 to 1854 during the Edo period, the Dutch were the only Europeans allowed to remain in the country. Thus, the Dutch language became an important way of learning about European science, technology, and medicine in Japan through the mid-1800s. Educated after 1854, when U.S. Commodore Matthew C. Perry forced Japanese leaders to open trade with the United States, Takamine’s family decided he should learn English. At age 12, he was sent to live with a Dutch family who could teach him the language.

Takamine attended the University of Tokyo, where he first studied medicine, like his father, before switching to chemistry. He graduated with a degree in applied chemistry in 1879. Afterwards, he was one of only a few students selected by the Japanese government to study at Anderson College (today, the University of Strathclyde) in Scotland. He made a habit of visiting industrial plants in his travels around Europe, where the chemistry of fertilizers fascinated him. After completing his studies in 1883, he returned to Japan and began work in the country’s Department of Agriculture and Commerce, where he was quickly promoted to head of the chemistry division.

A Honeymoon Trip to Find Phosphate Rock

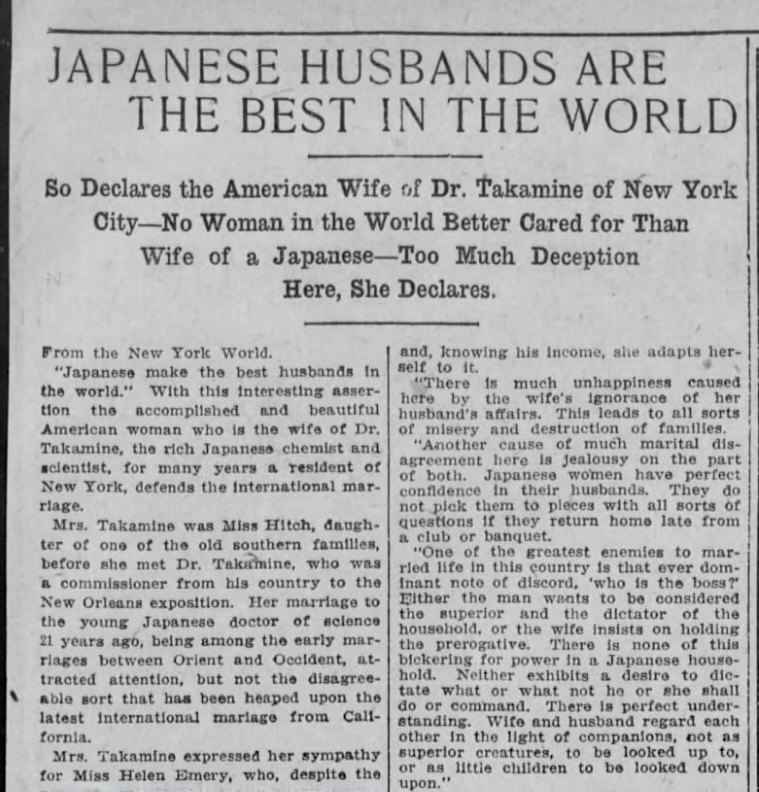

In 1884, only 30 years after the end of Sakoku, Takamine traveled to the Cotton Centennial Exposition—a world’s fair in New Orleans, Louisiana—on behalf of the Japanese government. There, he met Caroline Fields Hitch and they fell in love. Following a long-distance courtship, the couple married three years later. They dedicated their honeymoon to Takamine’s work, visiting fertilizer plants in North and South Carolina.

Takamine had become so interested in fertilizers that he founded the Tokyo Artificial Fertilizer Company (today, the Nissan Chemical Corporation) when he returned to Japan after the wedding. Through his company, he sought to demonstrate the principles of Wakan-yôsai, the adaptation and use of “Western concepts” to benefit Japan. Meaning “Japanese spirit, western technique,” this slogan was part of an effort on the part of the Meji Restoration to make Japan modern without changing its identity. The promotion of Wakan-yôsai was part of Takamine’s larger goal to promote international scientific cooperation.

LEARN MORE

Caroline Fields Hitch Takamine gave up her U.S. citizenship when she married Takamine in 1887. In 1909, she wrote an article for the Birmingham Post-Herald titled “Japanese Husbands Are the Best in the World.” Who do you think she was trying to convince, and why?

Diastase and Distilling

Around this time, Takamine noticed that Japanese methods of alcohol production differed from those used in North America. To create alcohol from grains, it is necessary to first convert those grains into sugar, a process known as fermentation. Distillers in the U.S. used partially germinated grains, or malt, as a basis of fermentation, which was very slow.

Japanese distillers, by contrast, used a specific mold that grew on rice fields known as koji, or Aspergillus oryzae. Known as Japan’s “national fungus,” A. oryzae produces an enzyme that consumes starch very quickly. It then produces the sugars needed to make alcohol as a by-product. Takamine found that by adding certain chemicals to the mold, he could accelerate the process of fermentation. He patented this product under the name Taka-diastase. A chemist with a keen sense for business, Takamine recognized that Taka-diastase could revolutionize U.S. distilling.

Takamine’s mother-in-law, Beatrice Fields Hitch, introduced him to one of the largest whiskey companies in the U.S. at the time. The Distillers’ and Cattle-Feeders’ company (also known as the “whiskey trust”) of Peoria, Illinois, was interested in using Taka-diastase, so the Takamines moved back to the United States with their two young sons in 1890. They settled in Peoria—then considered the whiskey capital of the U.S.—where the family founded the Takamine Ferment Company.

Although the media celebrated Taka-diastase as revolutionary, the product upset some competitors who believed he was disrupting the market for alcohol production with lower prices and faster production. They stoked anti-Japanese sentiment in this midwestern community at a time when anti-Asian discrimination in the U.S. was widespread. On October 8, 1891, the Manhattan Distillery, which housed his company, burned to the ground under mysterious circumstances.

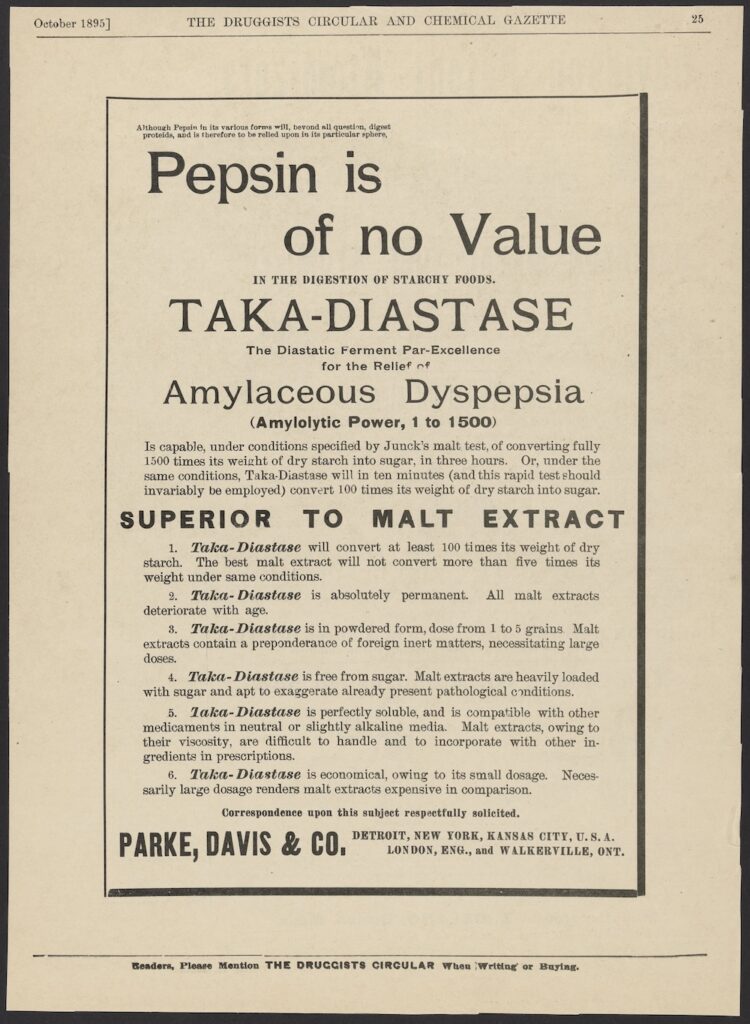

Collaboration with Keizo Uenaka

When the factory was rebuilt, the leaders of the whiskey trust decided they would end their contract with the Takamine Ferment Company. Takamine continued to advocate for the use of diastase and discovered that it could be used to treat stomach problems when he himself was sick in the hospital. This experience led him to license the patent for Taka-diastase to the Detroit-based pharmaceutical company Parke, Davis & Co., which rebranded it as a treatment for indigestion. With a steady income from the patent, he was open to new opportunities.

The general manager of Parke-Davis encouraged Takamine to study tiny hormone-producing organs known as adrenal glands next. He wanted Takamine to isolate a specific hormone from these tissues, which the manager and many others believed could have medical applications. Takamine agreed and in 1897, he opened a laboratory for this purpose in Clifton, New Jersey, just outside of New York City.

After three years without success, he realized that he could not solve this puzzle alone. He contacted Professor Nagayoshi Nagai at Tokyo Imperial University, where he had been a student. Nagai was mentoring a young chemist named Keizo Uenaka at the time, who he recommended for the job. Uenaka agreed and moved 12,000 miles from home to assist Takamine in his lab.

Uenaka arrived in February 1900, and the pressure was on. Two other academic researchers—Otto von Fürth of the University of Vienna and John Jacob Abel at Johns Hopkins University—were also competing to isolate the active substance in adrenal tissues. Uenaka and Takamine tried many different techniques. They sometimes even experimented on themselves to see if the substances they made were pure or not. Purity mattered because earlier medical uses of adrenal substances from animals often caused unpleasant side effects.

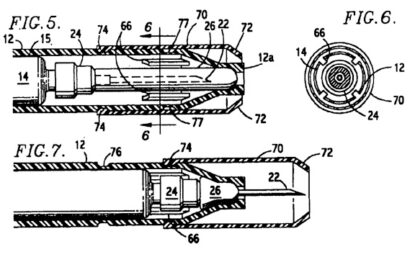

Within six months, Takamine and Uenaka had purified the hormone successfully, just before Abel. Ever the entrepreneur, Takamine immediately filed for his patent on “adrenalin” (without the final “e”). Though challenged by Abel, a court ruled that Takamine’s patent was valid. This product later became known as epinephrine, the precursor to the modern EpiPen.

LEARN MORE

In 1917, Takamine gave a speech on “American and Japanese Co-operation” to the National Conference on Foreign Relations of the United States. Would you expect a scientist to be involved in politics? Why or why not?

A Gift of Cherry Blossoms

Takamine’s patents made him rich. In his later life, he dedicated his wealth and connections to philanthropy. He donated large sums of money to support young scientists and to encourage Japanese-U.S. relations. Among other activities, he helped found the Japan Society in 1907 to “facilitate personal contact and mutual understanding between the Americans and the Japanese.” More specifically, the Society supported public exhibitions, lectures, and diplomatic banquets.

Takamine later hosted Japanese dignitaries at his home in New York and channeled money for cross-cultural programs through the Japanese consulate. He continuously advocated for business exchanges between the two countries, particularly with respect to the textile and porcelain industries. He donated thousands of cherry blossom trees on behalf of Japan in 1911. They still bloom in Washington, D.C., a symbol of the peace and friendship he wanted to cultivate.

Though Takamine faced discrimination in the United States, he wrote many newspaper articles and opinion pieces on the benefits of Japanese-U.S. relationships. He died in 1922, but his sons maintained the Takamine Laboratory in Clifton, New Jersey. His younger son, Ebenezer, became a U.S. citizen in 1952 under the new immigration quotas of the McCarran-Walter Act, a step his father could not have taken.

Glossary of Terms

Samurai

This term was originally used to describe Japan’s aristocratic warrior class. Over time, samurai moved into government and civil positions, though values like self-discipline carried over.

Back to top

Edo Period

Also known as the Tokugawa Period, this was a time of internal peace and stability from 1603 to 1876 under a military government.

Back to top

Meiji Restoration

A Japanese political revolution that ended the Edo Period in 1868, returning the country to imperial rule. It was followed by a period of rapid modernization and social change.

Back to top

Enzyme

A kind of protein that can break down and change different types of molecules or ingredients.

Back to top

Adrenaline

A hormone that is naturally made in human bodies, it is responsible for the “fight-or-flight” response. Used as a medicine, adrenaline helps stabilize heart rhythm and relieves respiratory issues, among other important uses.

Back to top

Further Reading

Takamine, Jokichi. 1914. “Enzymes of Aspergillus Oryzae and the Application of Its Amyloclastic Enzyme to the Fermentation Industry.” Journal of Industrial & Engineering Chemistry 6 (10): 824–28.

Takamine, Jokichi, and J. W. Bennett. 1988. Takamine: Documents from the Dawn of Industrial Biotechnology. Elkhart, Ind: Miles Inc.

Lee, Victoria. 2020. “Scaling Up from the Bench: Fermentation Tank.” In Boxes: A Field Guide. Mattering Press.

Yamashima, Tetsumori. 2003. “Jokichi Takamine (1854–1922), The Samurai Chemist, and His Work on Adrenalin.” Journal of Medical Biography 11 (2): 95–102.

You might also like

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Hennig Brandt and the Discovery of Phosphorus

An engraving hints at the ways art and science were intertwined in the Age of Enlightenment.

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

Alcohol Through the Ages

This 1928 publication features a collection of Kentucky Alcohol Corporation ads on distillation.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

A Mighty Pen

Discover the history of the EpiPen.