Stephanie L. Kwolek

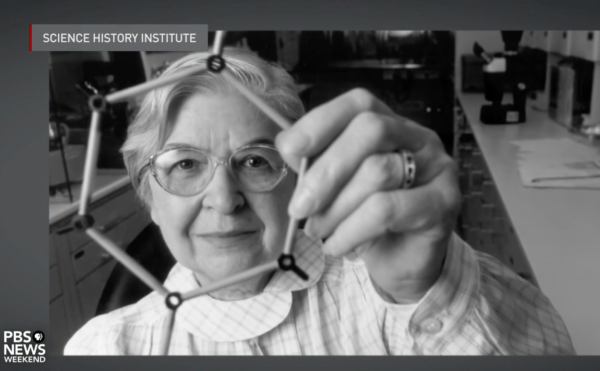

In a polymer research lab at DuPont, Kwolek discovered the super fiber known as Kevlar.

In 1965 Stephanie Kwolek created the first of a family of synthetic fibers of exceptional strength and stiffness. The best-known member is Kevlar, a material used in protective vests as well as in boats, airplanes, ropes, cables, and much more—in total about 200 applications.

Kwolek (1923–2014) was born in New Kensington, Pennsylvania. Her father, who died when she was 10 years old, was a naturalist by avocation. She spent many hours with him exploring the woods and fields near her home and filling scrapbooks with leaves, wildflowers, seeds, grasses, and pertinent descriptions. From her mother, first a homemaker and then by necessity a career woman, Kwolek inherited a love of fabrics and sewing.

At one time she thought she might become a fashion designer, but her mother warned her she would probably starve in that business because she was such a perfectionist. Later Kwolek became interested in teaching and then in chemistry and medicine.

LEARN MORE

Biography is one way of learning about a person. Oral history is another. Spend a few minutes listening to Stephanie Kwolek’s interview archived by the Science History Institute’s Center for Oral History. What do you hear? Has the recording picked up background noises, interesting accents, nervous laughter, or meaningful pauses? What might these tell you about the interview context, who is speaking, or how the speakers feel about the memories being discussed? What do think you can learn about Kwolek from her oral history that is different from the content of this biography?

College and DuPont

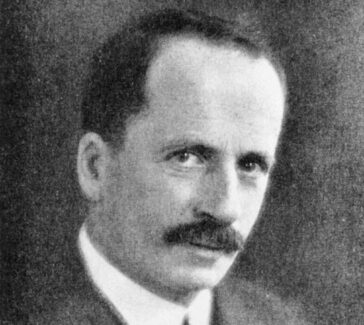

When she graduated from the women’s college (Margaret Morrison Carnegie College) of Carnegie Mellon University, she applied for a position as a chemist with the DuPont Company, among other places. Her job interview with W. Hale Charch, who had invented the process to make cellophane waterproof and who was by then a research director, was a memorable one.

After Charch indicated that he would let her know in about two weeks whether she would be offered a job, Kwolek asked him if he could possibly make a decision sooner since she had to reply shortly to another offer. Charch called in his secretary and in Kwolek’s presence dictated an offer letter. In later years she suspected that her assertiveness influenced his decision in her favor. At DuPont the polymer research she worked on was so interesting and challenging that she decided to drop her plans for medical school and make chemistry a lifetime career.

She was engaged in several projects, including a search for new polymers as well as a new condensation process that takes place at lower temperatures—about 0° to 40°C. The melt condensation polymerization process used in preparing nylon, for example, was instead done at more than 200°C. The lower-temperature polycondensation processes, which employ very fast-reacting intermediates, make it possible to prepare polymers that cannot be melted and only begin to decompose at temperatures above 400°C.

In Search of Super Fibers

Kwolek was in her 40s when she was asked by DuPont to scout for the next generation of fibers capable of performing in extreme conditions. This assignment involved preparing intermediates, synthesizing aromatic polyamides of high molecular weight, dissolving the polyamides in solvents, and spinning these solutions into fibers.

She unexpectedly discovered that under certain conditions large numbers of the molecules of these rodlike polyamides become lined up in parallel, that is, form liquid crystalline solutions, and that these solutions can be spun directly into oriented fibers of very high strength and stiffness. These polyamide solutions were unlike any polymer solutions previously prepared in the laboratory. They were unusually fluid, turbid, and buttermilk-like in appearance, and became opalescent when stirred.

The person in charge of the spinning equipment initially refused to spin the first such solution because he feared that the turbidity was caused by the presence of particles that would plug the tiny holes (0.001 inch in diameter) in the spinneret. He was finally persuaded to spin, and much to his surprise, strong, stiff fibers were obtained with no difficulty. Following this breakthrough many fibers were spun from liquid crystalline solutions, including the yellow Kevlar fiber.

Kevlar has gone on to save lives as a lightweight body armor for police and the military; to convey messages across the ocean as a protector of undersea optical-fiber cable; to suspend bridges with super-strong ropes; and to be used in countless more applications from protective clothing for athletes and scientists to canoes, drumheads, and frying pans.

Recognition

Kwolek received many awards for her invention of the technology behind Kevlar fiber, including induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1995, only the fourth woman member of 113 at the time. In 1996 she received the National Medal of Technology, and in 1997 the Perkin Medal, presented by the Society of Chemical Industry. In 2003 she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

Kwolek served as a mentor for other women scientists and participated in programs that introduce young children to science. One of Kwolek’s most cited papers, written with Paul W. Morgan, is “The Nylon Rope Trick” (Journal of Chemical Education, April 1959, 36:182–184). It describes how to demonstrate condensation polymerization in a beaker at atmospheric pressure and room temperature—a demonstration now common in classrooms across the nation.

In 2013 her story was told in a children’s book by Edwin Brit Wyckoff, The Woman Who Invented the Thread That Stops the Bullets: The Genius of Stephanie Kwolek. Kwolek died in Delaware at the age of 90.

You might also like

VIDEO

The Life and Achievements of Chemist Stephanie Kwolek, Inventor of Kevlar

Watch this PBS News Weekend “Hidden Histories” episode, which features resources from the Institute.

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

Women & Science Collection

Materials related to notable women scientists as well as images of women working in a variety of laboratory and industrial settings.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

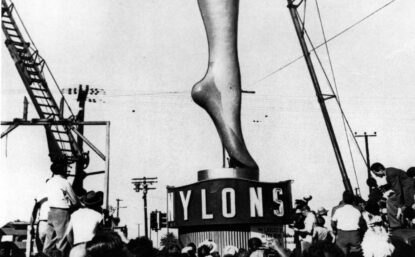

Nylon: A Revolution in Textiles

The invention of nylon in 1938 promised sleekness and practicality for women and soon ushered in a textile revolution for consumers and the military alike.