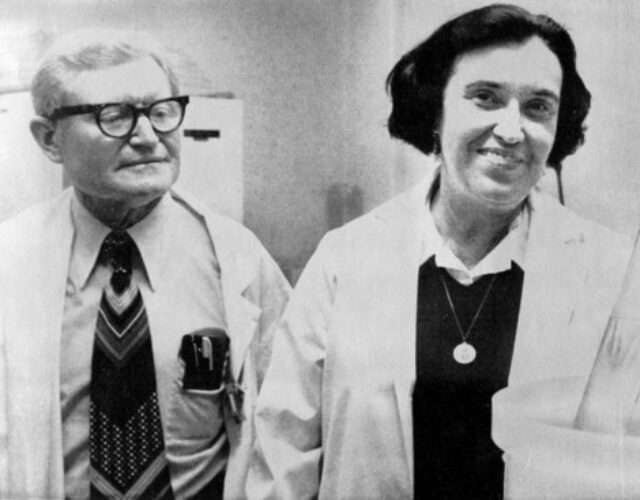

Rosalyn Yalow and Solomon A. Berson

Yalow, a resourceful young researcher, and Berson, a multitalented medical doctor, used radioactive isotopes to study what happens inside the human body.

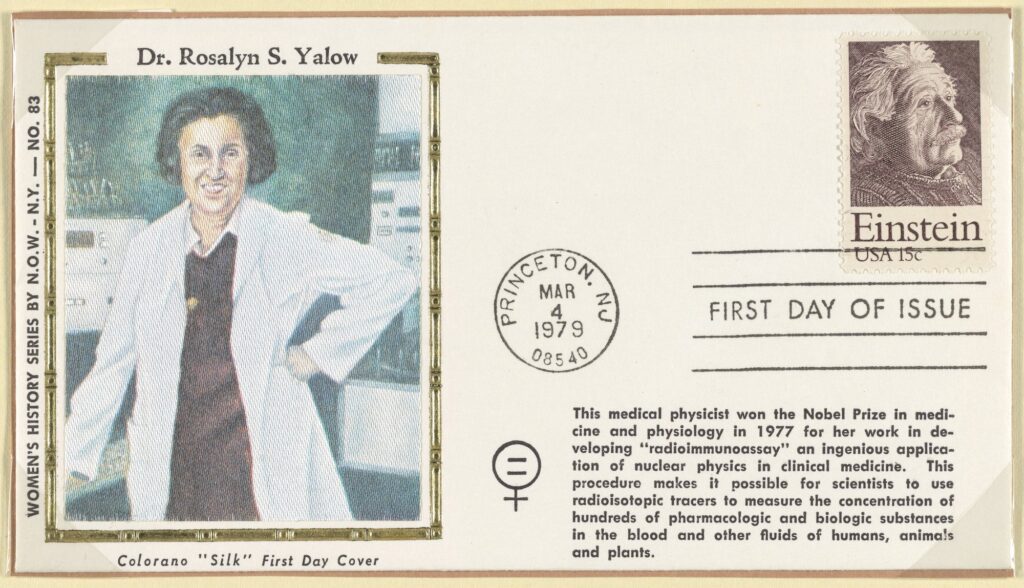

Working out of an old janitor’s closet for a laboratory, the team of Rosalyn Yalow and Solomon Berson went on to do groundbreaking research in techniques for the early detection of diseases, including radioimmunoassay, for which Yalow received the Nobel Prize.

Radioimmunoassay (RIA) is a technique that uses radioactive materials to investigate the human body for tiny amounts of substances. It is especially important for the early detection of diseases. Two researchers at a Veterans Administration (VA) hospital in the Bronx, New York, developed the technique in the late 1950s. They were Rosalyn Yalow (1921–2011) and Solomon A. Berson (1918–1972).

Hearing the Call of Science

Yalow was born Rosalyn Sussman and grew up in New York City on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Though her parents never finished high school themselves, they realized the value of educating their children and encouraged their daughter and son to read books from the local library. In junior high school Yalow was attracted to math, but by high school she had changed her career plans to chemistry, thanks to a talented chemistry teacher. Once at New York’s Hunter College, however, she switched from chemistry to physics, having received more encouragement from her physics professors than from the chemistry faculty.

Also while in college Yalow read Eve Curie’s biography of her Nobel Prize–winning mother, Marie Curie, which excited Yalow about nuclear physics, a hot new field in the late 1930s. A 1939 lecture by Italian scientist Enrico Fermi on nuclear fission, which had just been discovered by Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner, and Fritz Strassmann, made Yalow even more determined to pursue a career in nuclear science.

Breaking Barriers

Though she hoped to attend graduate school after Hunter, it was hard for a Jewish woman to get accepted to a university in 1941. At first she took a job as a secretary to a professor at Columbia University, with the understanding that she could eventually take graduate physics courses there. But U.S. entrance into World War II was looming on the horizon, and many male graduate students were either being drafted into the military or being sent to work on secret wartime research projects.

Suddenly there was a shortage of graduate students at universities, and women students were recruited to take the places of the men who were leaving. Yalow was accepted by the University of Illinois, and she arrived there in September 1941 as the first woman graduate student in the physics department at Illinois since 1917. There she met and married (in 1943) Aaron Yalow, also a graduate student in physics.

After earning her doctorate in 1945, Yalow returned to Hunter College, this time as a teacher. The war was over, and her classes were filled with veterans attending college thanks to the G.I. Bill, which paid for their education. In 1947 her husband introduced her to Edith Quimby, a physicist at Columbia University who specialized in the medical use of radioactive isotopes.

Yalow offered to volunteer at Quimby’s lab, but instead Quimby introduced her to Gioacchino Failla, an influential person in the field of medical physics. One phone call from Failla to the VA hospital in the Bronx, and Yalow was offered a part-time job as a researcher there. For the next few years she split her time between teaching at Hunter and working at the VA, until finally going full time at the VA in 1950.

Yalow and Berson Team Up

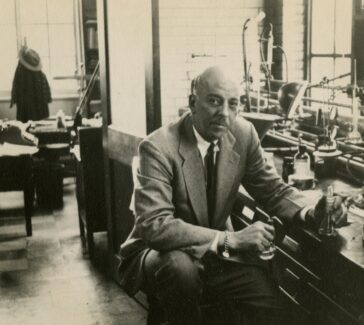

At first Yalow had only an old janitor’s closet to use as a laboratory, and since her field was so new, she often had to build her own equipment. In 1950 Solomon Berson, a highly recommended medical doctor, came to work with her. For the next 22 years Yalow and Berson worked together using radioactive isotopes to study what happens inside the human body.

When Berson dropped by to interview with Yalow, he had already accepted a position at the VA hospital in Bedford, Massachusetts. The two hit it off famously, posing mathematical problems for each other, causing Berson to cancel his earlier career plans. Berson too had grown up as a brilliant child in New York City. His Russian immigrant father applied his chemical engineering degree from Columbia University in the fur-dying industry. Young Berson became an accomplished violinist and chess player among other developed talents.

After graduating from the City College of New York in 1938, he applied to several medical schools but was not accepted. Instead he received an MS degree at New York University and began to teach anatomy in NYU’s dental school. In 1941 he was admitted to NYU’s medical school and subsequently served his internship at Boston City Hospital and his residency at the Bronx VA hospital, where he encountered Yalow.

Insulin Research

In one early project Yalow and Berson studied diabetes. Diabetic patients have trouble metabolizing sugar because their bodies do not make enough insulin, the pancreatic hormone essential for sugar metabolism. They take injections of insulin to correct this problem. Yalow and Berson wanted to study what happened to insulin once it was injected into the body.

To help trace the hormone the two scientists added an atom of a radioactive isotope of iodine, iodine-125, to the insulin molecule, a technique called labeling. The radiation given off by the iodine-125 atom would help them follow the insulin molecule through the body. For example, if radiation was found coming from a patient’s urine, they would know that the insulin molecule had been broken down by the body and its iodine-125 atom had been passed out of the body through the urine.

Yalow and Berson noticed that diabetic patients who had been taking insulin for some time kept the labeled insulin in their bodies longer than healthy people. In those days diabetic patients usually used cattle insulin, which is slightly different from human insulin. When the body detects a foreign substance, it attacks it with antibodies. Yalow and Berson realized that the insulin-taking diabetics in their study had previously developed an immune response to the cattle insulin and formed antibodies, and that these antibodies were binding to the labeled insulin molecules, slowing them down.

This immune response also made it harder for the body to use the insulin. Through this discovery the two scientists realized that human insulin would be better than cattle insulin for diabetic patients. The human body would not attack human insulin. Genetically modified bacteria were eventually engineered that could produce large amounts of human insulin. Today nearly all the insulin used to treat diabetes is produced by genetically modified bacteria.

Radioactive Labeling: Radioimmunoassay

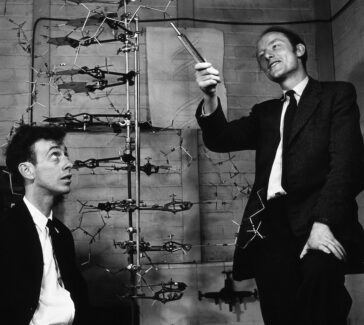

The most famous discovery made by Yalow and Berson was a technique called radioimmunoassay, or RIA, a method of quantifying minute amounts of biological substances in the body using radioactive-labeled material. Measuring the concentrations of various chemical compounds in the human body is important for diagnosing diseases and for making sure a medicine is working properly, but many compounds are present in the blood in such low concentrations that measuring them can be difficult. RIA makes the job much easier.

With RIA a known quantity of the substance that the researcher wants to measure—a hormone, in Yalow’s and Berson’s case—is tagged with a radioactive isotope. Then it is mixed in solution with its naturally occurring antibody (the “immuno” part of RIA), and hormone-antibody pairs are formed. They are then added to a quantity of the patient’s blood, in which there is an unknown quantity of the hormone that the researcher wants to determine. Since antibodies prefer nonradioactive versions of the hormone to radioactive ones, they gradually separate from their radioactive partners and team up with the natural hormone.

A researcher then separates out all the hormone-antibody pairs (both the radioactive and the nonradioactive ones) and measures the radioactivity of the mixture. The difference in the level of radioactivity of this mixture from the radioactivity of the original sample of tagged pairs gives a measure (“assay”) of how much natural hormone was in the sample of blood.

Nobel Prize

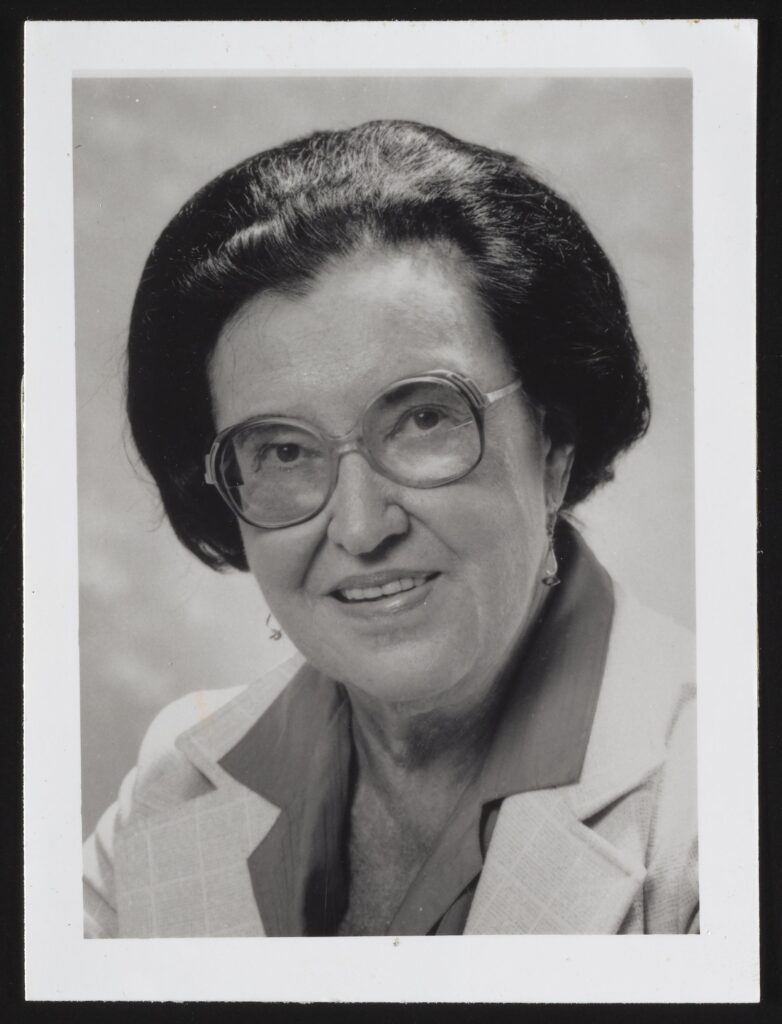

In 1977 Yalow received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her and Berson’s development of RIA as it applied to tracing hormones in the body. Since Nobel Prizes are only given to the living, Yalow received the award without Berson, who died in 1972. She shared it with two other scientists, who were honored for their work on hormone production in the brain.

Yalow named the lab at the VA hospital in the Bronx—which by 1972 was much larger than the janitor’s closet where she had started out—for Berson so that his name would still be on every paper she published as long as she worked there.

In addition to receiving the Nobel Prize, she was the first woman to receive the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award (1976), and in 1988 she was awarded the National Medal of Science by President Ronald Reagan. She continued to conduct and direct research at her VA lab until her retirement in 1991. Yalow was a distinguished service professor at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.