Robert W. Parry

A champion of scientific literacy, Parry was an inorganic chemist who devoted himself to education.

Intensive mentorship helped Robert W. Parry (1917–2006) overcome early economic barriers to achieve an award-winning career in chemistry. He went on to become a leader in chemical education in his own right.

The Influence of Mentors

“All of my education has been governed by finances,” Parry recalled in his oral history. Born in Ogden, Utah, in 1917, Parry’s family nurtured early interests in the physical sciences. These settled decisively on chemistry two years into Parry’s undergraduate education at Weber State College. Forced to step away from coursework when he ran out of money to pay for school, Parry found he could support himself as a chemical analyst with the Forest Service Research Laboratory in his hometown.

“The thing that made it chemistry for sure was that the Forest Service paid me,” Parry later said of this turning point in his undergraduate education. The job opened doors. Through the Forest Service, Parry met agronomist Rudger H. Walker, who encouraged Parry to continue his studies at Utah State University and helped Parry find a campus job analyzing soils.

Walker helped Parry secure several graduate appointments, leading to a master of science degree in soil chemistry from Cornell University in 1942. “He made my life for me…almost,” Parry later said of Walker’s influence. By this time, the United States was mobilizing industry for World War II. DuPont invited Parry to apply his technical skills to the war effort. This took him to DuPont’s new factory in Kankakee, Illinois, where he worked on tetryl, a very dangerous explosive compound that the U.S. Navy used during the war. After DuPont, he joined the Munitions Development Laboratory at the University of Illinois. There, he earned his PhD in inorganic chemistry under John C. Bailar, another chemist known for his commitment to mentoring students.

Building Tools and Institutions

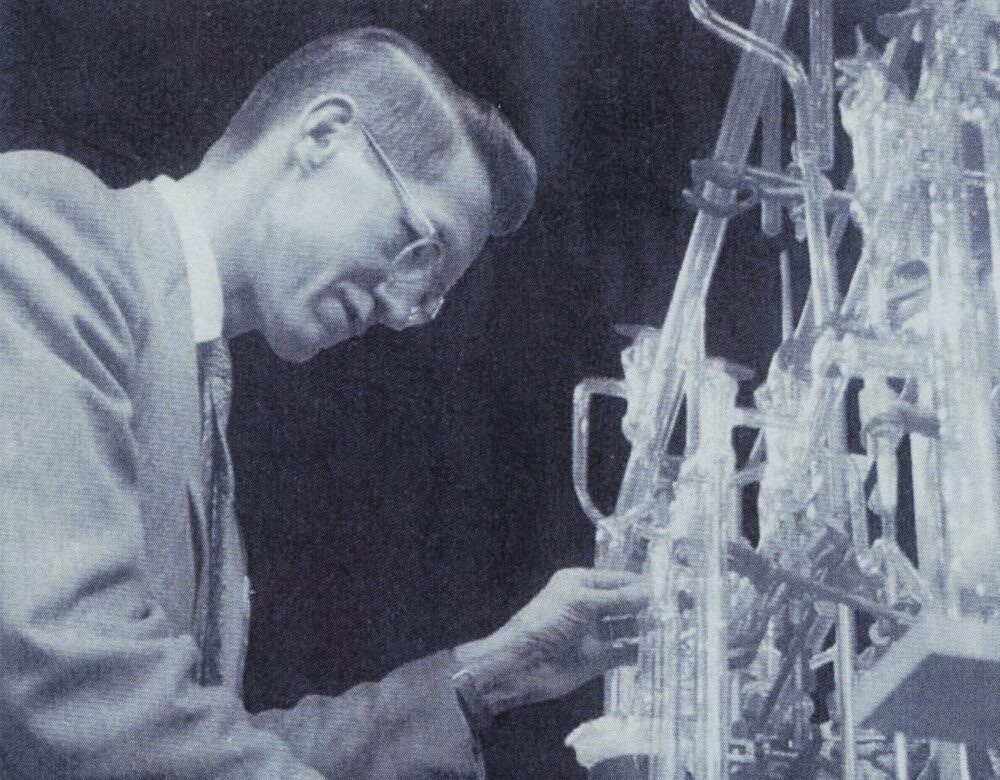

After completing graduate studies in 1946, Parry became a lecturer at the University of Michigan, where he turned to the chemistry of the boron hydrides, among other topics. The boranes, compounds involving borane and hydrogen, attracted a lot of strategic interest during and after World War II as possible jet fuel additives and as materials for enriching uranium isotopes, though these possibilities never became reality. Because of their volatility and tendency to burst into flame, these compounds require special handling involving the use of a vacuum line—a sealed glass system under a high vacuum.

Parry’s research group at Michigan contributed significantly to the development of this laboratory apparatus. At the same time, research on these unusual compounds shed light more generally on patterns of chemical structure and bonding. These studies informed a major publication, “Systematics in the Chemistry of the Boron Hydrides,” which Parry co-authored with L. J. Edwards of the Callery Chemical Company in 1959.

LEARN MORE

This Detroit Sunday Times article highlights techniques that Parry developed to work on boron hydrides. The author writes: “much of man’s progress has consisted of some scientist discovering some ‘useless’ fact just because it was a fact. That is basic research.”

What is the author’s broader point about “basic research?” Do you agree or disagree, and why?

In 1969 James C. Fletcher, a physicist who was successful in business and served two terms as NASA administrator, lured Parry from Michigan to the University of Utah. Initially Parry was reluctant to leave his well-equipped lab at Michigan. Fletcher argued that at Utah, Parry wouldn’t just be able to practice chemistry. He would also have a direct hand in the creation of a “high-quality institution,” as Parry put it. The strategy worked, and Parry enjoyed significant patronage in support of his efforts to build a robust chemistry program in his home state.

Chemical Education

As a faculty member at the University of Michigan and the University of Utah, education was a primary concern for Parry. He was remembered to have given his students a secret knock, for instance, granting them access to his office above all others during an especially busy period when he served as editor of the journal, Inorganic Chemistry. He was deeply involved in activities of the American Chemical Society (ACS), especially those involved with chemical education.

In 1960 he contributed to the first draft of the Chemical Education Material Study with a group including Glenn T. Seaborg, George C. Pimentel, and J. Arthur Campbell. The CHEM Study was one of two major high school chemistry educational programs funded by the National Science Foundation after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first human-made Earth satellite, in 1957. This event raised concerns that U.S. scientific and technical education were not sufficiently competitive, prompting intensive evaluation and investment. The CHEM Study was meant to improve the teaching of high school chemistry by replacing earlier emphasis on memorization and long-accepted theories with laboratory experimentation.

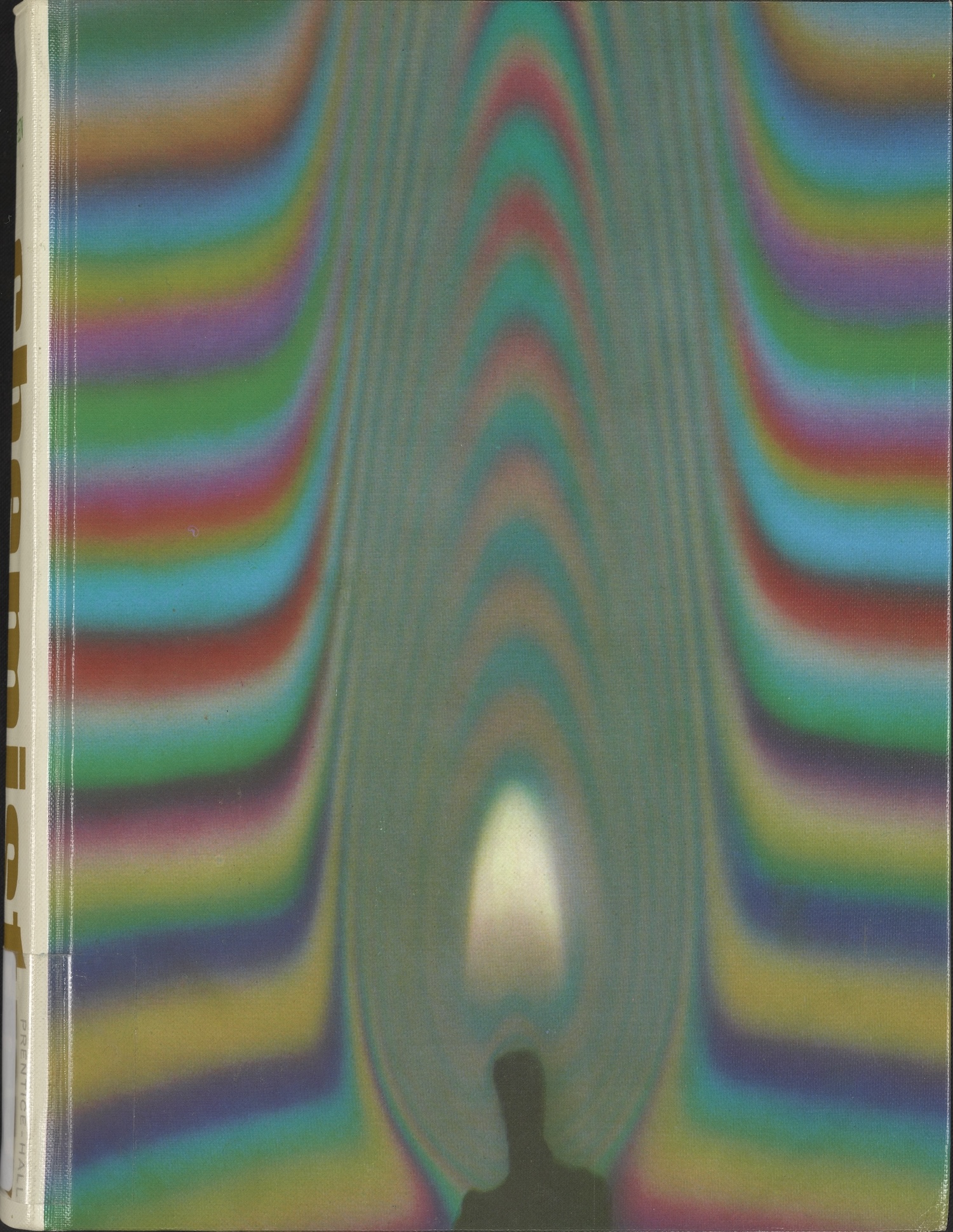

In 1966 the CHEM Study adopted a revision scheme designed to ensure a steady supply of textbooks that would “keep pace with the accelerating movement of science.” Bids were entertained from a wide range of “scientist-teacher author teams,” and Parry’s was successful. This led to the 1970 publication of Chemistry: Experimental Foundations, coauthored with Luke Steiner of Oberlin College and high school chemistry teachers Phyllis Dietz and Robert Tellefsen.

LEARN MORE

The caption for this book cover image says that it “depicts a lighted candle silhouetted against the multicolored interference pattern produced by a Michelson interferometer using white light. The brilliant light of the interferometer has washed out nearly all the light of the flame, but the hot gasses from the flame have sharply deformed the interference pattern and produce a large discontinuity on the edge of the flame. This unique view of the candle symbolizes our revision, which takes a new look at chemistry as a dynamic and distinctly contemporary science.”

What is the point of this analogy? What do you think the flame and the interference pattern stand for specifically?

In recognition of his teaching—through which he mentored thousands of undergraduates, more than 60 PhD students, and numerous postdoctoral fellows—Parry was awarded the 1977 ACS Award in Chemical Education and the 1978 Utah Award for Service to Chemical Education. Further awards for chemical education were named in his honor. At the University of Michigan, former students helped to establish the Robert W. Parry Award for Graduate Students in 1984. In 2011 Rodney and Carolyn Brady created the Parry Teaching Award at the University of Utah to honor “a faculty member,” who like Parry, “demonstrated a special motivation and ability in stimulating the interest of high school and undergraduate students in the study of…chemistry.”

Parry’s commitment to chemical education extended well beyond the classroom—it also motivated his editorial work and his investment in science journalism. He was a champion of scientific literacy who wrote passionately about the need for U.S. leaders to wrestle with the uncertainty inherent in experimental science. “In my judgment,” he once wrote, “our survival depends not only upon the rapid procurement of knowledge, but upon its transmittal in understandable form to those making our laws.”

Reflecting on the main theme of his career, Parry reasoned that research is just one aspect of teaching. In a 1992 interview, he said, “I set out in life to be a teacher,” and he named teaching undergraduates as “one of the more pleasurable callings in life.” At the same time, he considered it his duty to teach advanced students, too: “In collaboration with graduate students, you do basic research, which in the end serves to teach the world.”

Further Reading

Eisenberg, Richard. (2007) “A Salute to the Founding Editor, Robert W. Parry (1917-2006).” Inorganic Chemistry 46(5): 1509-1510.

Merrill, Richard J. and David W. Ridgway. (1969) The CHEM Study Story: A Successful Curriculum Improvement Project. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Parry, Robert W. (1977) “Who Pays the Piper?” Journal of Chemical Education 54(9): 522-525.

Wolfe, Audra J. (2020) Freedom’s Laboratory: The Cold War Struggle for the Soul of Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Featured image: Robert Parry performing research using a vacuum line. Courtesy University of Michigan.

You might also like

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

Oral History: John C. Bailar

Listen to an interview with the University of Illinois inorganic chemist who was Robert Parry’s mentor.

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

25th Anniversary Celebration of ACS’s ‘Journal of Inorganic Chemistry’

Watch a video from an American Chemical Society dinner featuring a speech by Robert Parry.

DISTILLATIONS PODCAST

Communicating Chemistry

How do scientists explain what they do to the larger public, and how can historians help?