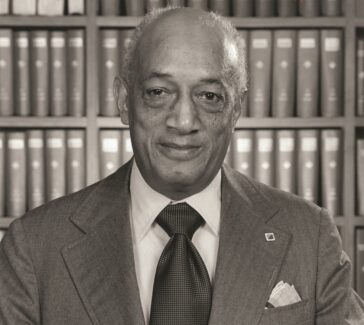

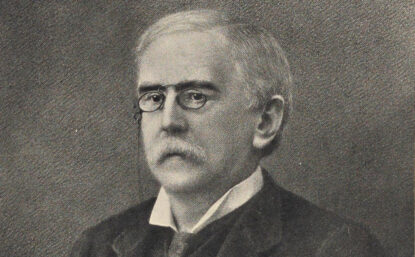

Petr Rehbinder

The Soviet physical chemist discovered that a film of lubricant weakens the surfaces of materials, especially metals and rocks. This was an early example of the influence of mechanochemical effects.

The career of Petr Rehbinder (1898–1972) connected pure science and industrial technology. He developed a theory that explained how surface-active substances reduce the hardness of materials—and proved it experimentally. The theory quickly brought about industrial innovations and has been extended to new materials over time.

On a Fast Track to Scientific Prestige

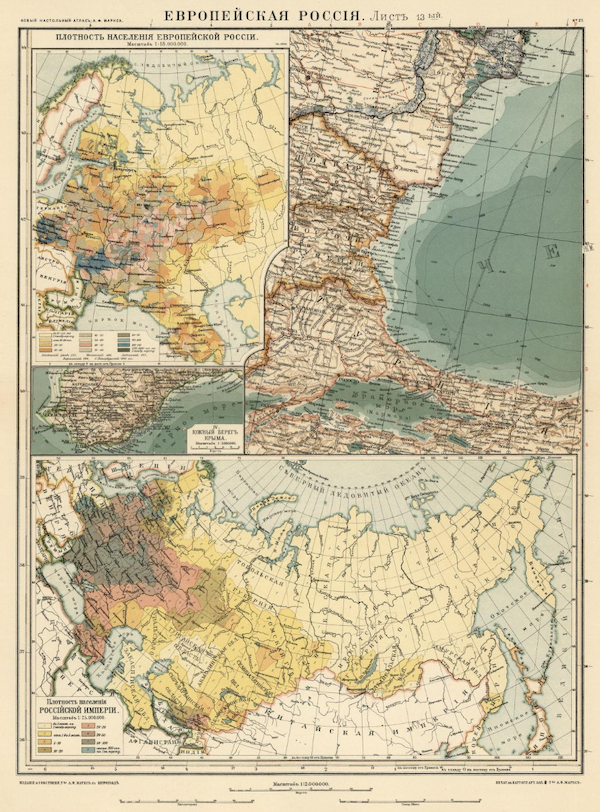

Rehbinder was born on October 3, 1898, in St. Petersburg, which at the time was the capital of the Russian Empire. His mother was a schoolteacher and his father, a distant descendant of Swedish nobility, was a navy physician. In his family, education was fostered from early childhood. Rehbinder learned to read and speak German at home and became fluent in French. Both languages would later serve him well in his scientific career.

His father died when Rehbinder was young and he was raised by his mother and grandmother. They moved to the city of Yalta in Crimea, and then travelled around Europe. He attended schools in Germany, Switzerland, and France, and finished high school (known in that context as a “gymnasium”) in the southern city of Kislovodsk when the family returned to Russia.

By the time Rehbinder reached adulthood, the country had undergone a drastic political change. The October Revolution of 1917—the final phase of overthrowing the Russian monarchy—was in full swing. The Bolsheviks, a far-left faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labor Party led by Vladimir Lenin, seized political power. But this Revolution was not universally accepted, resulting in a violent civil war between 1918 and 1922. The Bolsheviks became the sole legal party in the new Soviet state, and they later became the Communist Party. This state soon expanded to become the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.).

Rehbinder started school at Rostov University in southern Russia in 1917, but was not able to finish his studies due to the turmoil and hardships of the Russian Civil War. In 1922 Rehbinder moved to Moscow to take two additional years at the university toward a degree in molecular physics, thermodynamics, and mathematics. By then, the city was the new capital of a new country. Many things in society were in flux, including the Russian Academy of Sciences, which oversaw almost all scientific activity in the nation for more than 200 years. If an ambitious student wanted to advance as a scientist, the Academy was the place to work.

Very early in his scientific career, Rehbinder found an exciting area of research that was poorly understood and understudied: surface phenomena in disperse systems. As a scientist who was well-read, competent in several disciplines (chemistry, thermodynamics, and mathematics), and good at experiments, he had a strong skillset for solving scientific puzzles. Fluency in the languages of science at the time—French and German—allowed him to read papers of European colleagues who were working on similar problems. The atmosphere of academic freedom and intellectual engagement at the Academy encouraged him to propose an innovative idea.

The Flow of Steel

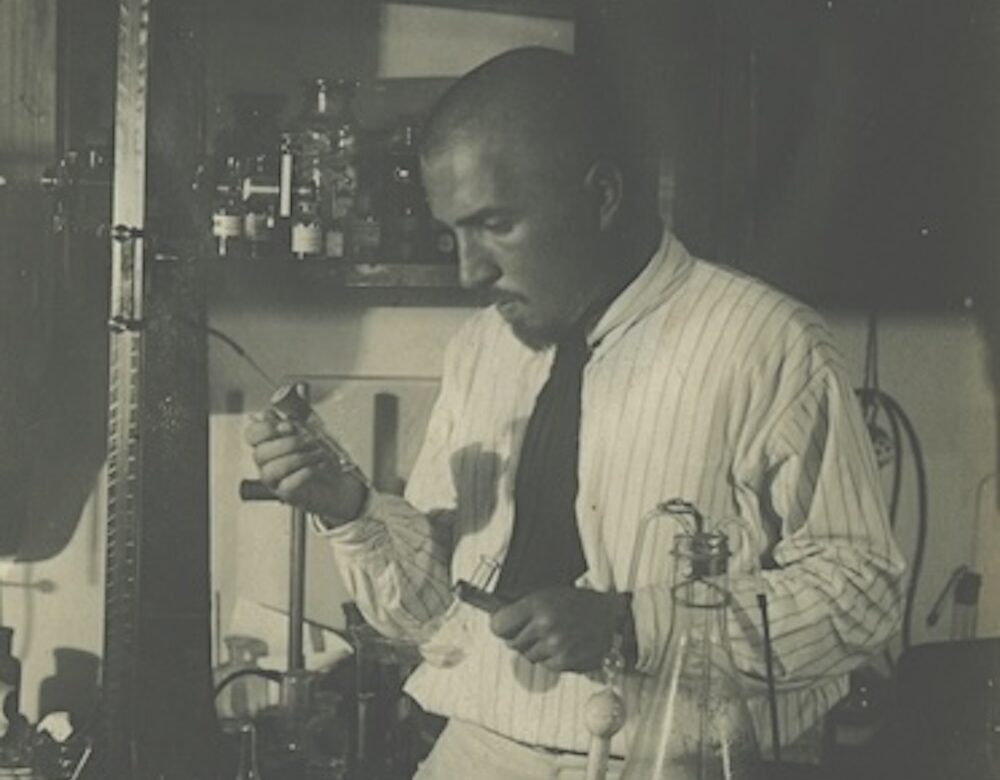

Hear Petr Rehbinder (pictured 4th from left) talking in his mother tongue about late nights in the lab and the relationship between science and technology. This interview, conducted by Russian philologist Victor Dmitrievich Duvakin, was recorded on February 9, 1971. Read a translated transcript.

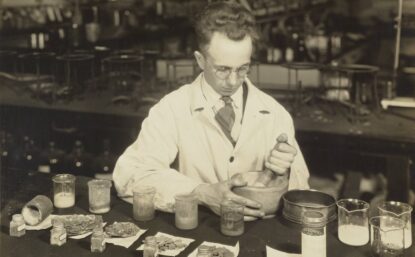

Even though he was still taking courses at Moscow University, Rehbinder started work as a junior researcher at the new Institute of Physics and Biophysics. Later, he would remember his early days as a time of vigorous discussions, bold experimentation, and unrestricted scientific curiosity. Researchers would come to the Institute as they pleased and stay up late into the night. They would gather for interdisciplinary colloquia led by the Institute’s director, the physicist and physician Petr Lazarev, and challenge each other to defend their theories. They shared a passion for solving scientific problems.

In 1928, at the age of 30, Rehbinder had an unintended breakthrough. He was working on a theoretical solution that would explain the influence of the energy of surface crystals on their mechanics. To test the hypothesis, he conducted a series of experiments with colleagues from the Institute. He discovered that polar surfactants brought into contact with the surface of metals, particularly those with single crystals, lose mechanical strength and ductility. In other words, when a liquid is adsorbed on the surface, it lowers the overall surface free energy. This reduces the bonding between the outermost atomic layers of the metal to those below the surface, which allows the surface to “soften.”

LEARN MORE

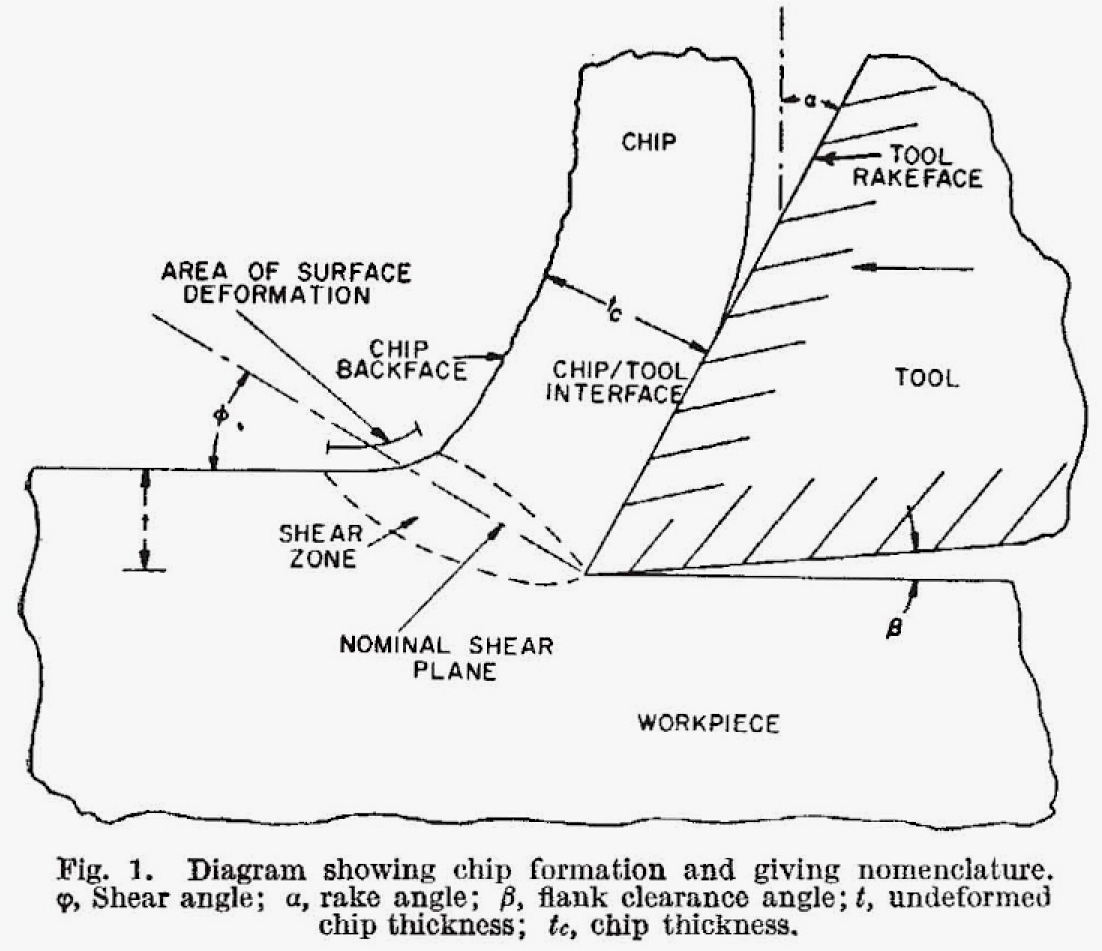

In mechanochemistry today, there is a process known as liquid assisted grinding (LAG), which is similar to the effect Rehbinder described. It has been found that by adding a small amount of liquid to solid materials, it is possible to increase the amount of product obtained in a chemical reaction. Mechanochemists today represent the Rehbinder effect with graphics that are similar to the one shown at right.

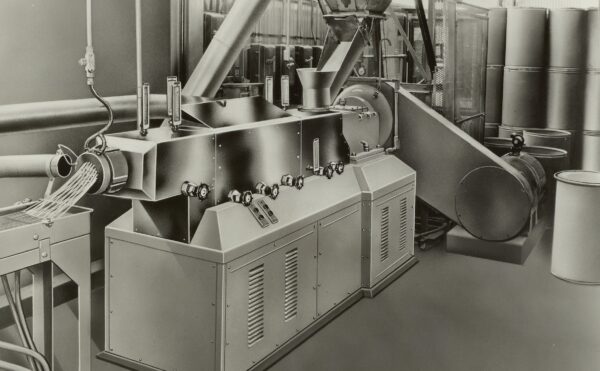

For the rapidly growing Soviet industry, this new discovery held tremendous potential. For instance, it could be applied to building heavy machinery. Rehbinder was awarded two doctorates, in chemistry and physics, without having to write or defend a thesis. Soon he became the leader of another newly formed research facility, known today as the Institute of Physical Chemistry, and in 1933 he was elected a corresponding member of the Academy. Applications of the Rehbinder effect became central to oil prospecting, mining, and precision machining. As new materials and technologies have been created—plastics, for example—more applications have been found for the effect.

By the 1930s everyone in the young Soviet republic was expected to contribute the growth and wellbeing of the state. The hierarchies of privilege by birth were turned upside down. The proletariat—people from humble backgrounds who earned a living by doing skilled or unskilled labor—was proclaimed the ruling class. They were thought to have the strongest motivations to support the new socialist regime, unlike people of noble birth. Those who had prospered in the old imperial system could not be trusted, as it was thought that it would be in their interest to see it return and the new regime fail. Some fell under suspicion and were persecuted.

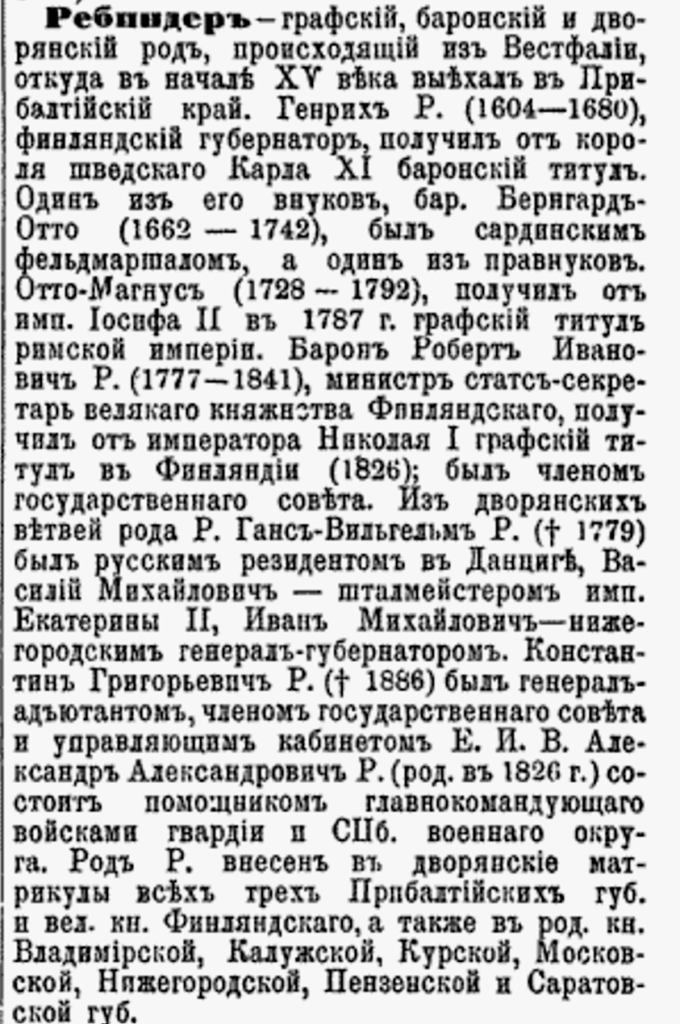

There was no way for Rehbinder to conceal his ancestry or escape suspicion. The old imperial encyclopedia contained an entry under the letter “R” detailing the history of his family. Later in life, he said that, luckily, neither he nor his father carried a noble rank, a title of a baron or a count. During the Great Purges, however, anyone could be indicted for suspicion of treason on random charges. This was a time when politicians, state officials, military officers, and even civilians were purged from the Soviet Union as an attempt for Joseph Stalin to consolidate power.

Though not a Communist Party member, Rehbinder was a staunch supporter of the regime. As a scientist, he made valued contributions to developing national industry and economy. Applications of his effect revolutionized drilling in oil and mineral mining, promoting access to natural resources that powered the economy. In heavy engineering, his work facilitated precision milling, grinding, and metal processing, yielding powerful machines. Decades after his death, researchers would recognize the significance of Rehbinder’s research for the new field of mechanochemistry.

Nonetheless, Pravda published an unfavorable review of his work in 1939. This might have been enough to end his career, or even his life. But friends from the Academy defended Rehbinder and he survived the blow. He went on to lead the department of Physical Chemistry at the D. I. Mendeleev Moscow Institute of Chemical Technology in 1940, and then was appointed head of the Department of Colloidal Chemistry at Moscow State University in 1942, where he organized experimental research on the properties of polymers, technologies for manufacturing heavy-duty construction materials, and composition of rock media and soils. In 1946 he was elected a full member of the Academy, the highest level of recognition for his scientific work.

Research and Organizational Legacy

Rehbinder was known to carry a school notebook everywhere he went, and to jot down ideas as they came. Early in their marriage, his wife, Elena, wanted to get a university degree and begin a professional career. He convinced her to abandon this ambition and to become his assistant, a so-called “faculty wife” instead. She typed academic publications and reports from his dictation whenever it was needed, kept the house ready for guests, and relieved her husband of worries about daily wants—бытовые заботы in the Russian language—so that he could focus on his work. Convalescing from a heart attack, Rehbinder once told his family that his next project would be to find ways to remove plaque and blockages from human blood vessels with the use of surfactants.

In 1968 Rehbinder co-organized the “All-Union Symposium on Mechanoemission and the Mechanochemistry of Solids” at a conference on colloid chemistry in Voronezh, located in the southwestern part of Russia. The meeting helped define a community with shared research interests. Such gatherings are, in fact, a common early step in the organization of a new scientific field. In the following years, annual Soviet conferences on mechanochemistry helped to further establish it as a distinct specialization within chemistry. Mechanochemists who have since looked into the early history of their field have debated whether or not the Rehbinder effect was a precursor to work on chemical reactions by grinding taking place today. These debates highlight the challenge of crediting any single individual with the birth of a new way of doing science.

LEARN MORE

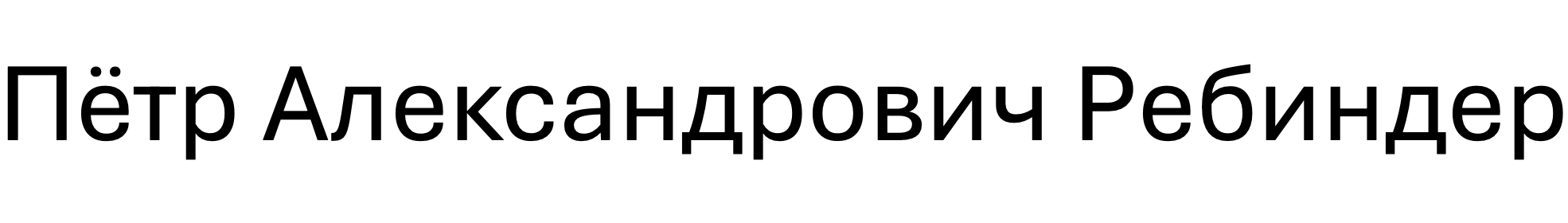

Here is how Rehbinder’s full name looks in the Russian version of the Cyrillic alphabet. Here, we include the patronym—that part of Rehbinder’s name derived from his father’s given name. In Russian, the patronym occupies the place a middle name would in English-speaking cultures.

Glossary of Terms

Disperse Systems

A mixture whereby fine particles of one substance are scattered throughout another substance.

Back to top

Surfactants

Substances that reduce surface tension when added to a liquid, increasing its ability to spread.

Back to top

Ductility

The ability of a material to stretch, bend, or spread without breaking.

Back to top

Great Purges

In the 1930s under Josef Stalin, this policy eliminated individuals who opposed the regime or whose convictions or influence could present a potential threat.

Back to top

Pravda

A widely circulated daily newspaper, the mouthpiece of the Communist Party.

Back to top

Further Reading

Rehbinder, Petr. “New Physico-Chemical Phenomena in the Deformation and Mechanical Treatment of Solids.” Nature 159 (1947): 866-7.

Takacs, Laszio. “Two Important Periods in the History of Mechanochemistry.” Journal of Material Science 53 (2018): 13324–13330.

“Academician P. A. Rehbinder,” Nature 240 (1972): 368.

Transcript

Back then, we came to the Institute whenever we wanted and left work late at night. There were no timecards, no sign-in sheets, no timekeeping tokens at the entrance. It was completely inconceivable: there were no other things to do but work on your science. […] One thinks about that time with joy, even though it is obvious to any scientist who is active today that the link between science and industry was much weaker then. The industry demands on science were not as broad and fundamental as now, industrial production did not drive science as much as it does currently when it lays its claims, and because of that there was significantly less organizational work that is now unavoidable. These days, every prominent scientist must be an administrator in their field. It eats up a lot of time and robs academicians and even regular professors of a chance to do hands-on work if we are talking about experimental research. Despite the fact that every experimenter considers it a joy to continue in their creative environment, with the equipment. Back then, that joy was palpable.

It does not mean that science is worse now than it was. Science has turned into an advanced, mighty force that powers technological development, which connects to features of contemporary time that did not exist then. I just want to say that we studied and worked—the young and the old all—as we saw fit. We wrote no reports; our publications were our reports. And, unlike our colleagues in the humanities, we wrote in such a way that the writing process was the final phase after excruciating experimental and theoretical research, when after analyzing the ideas or experiments, one would make what ignorant people call a discovery. We never call them discoveries, if we did, we would have to say that we make tiny discoveries every day because a chain of these discoveries constitutes the work of a scientist—a physicist, a chemist, a biologist.

Support

This biography was made possible by a collaboration between the Science History Institute and the Center for the Mechanical Control of Chemistry under NSF Grant #CHE-2303044, and Texas A&M University.

You might also like

DIGITAL EXHIBITIONS

Mechanochemistry

Explore two online stories about the ancient technique of crushing that remains central to our lives today.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

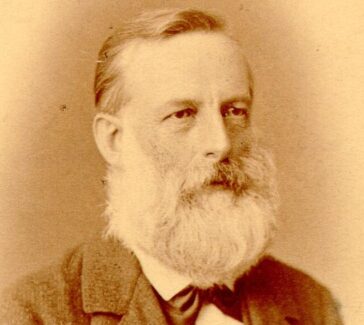

Matthew Carey Lea and the Origins of Mechanochemistry

A reclusive expert of 19th-century photography laid the foundation for green chemistry solutions emerging today.

COLLECTIONS BLOG

A Crushing Task

On the hunt for the historical sources of an underappreciated field: mechanochemistry.