Mary Engle Pennington

A chemist, inventor, and entrepreneur who transformed the U.S. refrigeration industry in the early 20th century, Pennington helped ensure year-round access to foods free from bacterial contamination.

Mary Engle Pennington (1872–1952) developed many of the earliest scientific standards and equipment for the “cold chain,” the system of temperature-controlled processing, storage, and transportation of perishable products. This system linked farms to consumers, making modern urban life possible.

Finding a Vocation

Pennington grew up in an era when there were very few professional women scientists. Her father was a successful manufacturer, and young women from wealthy families like hers were not expected to pursue a career. Nonetheless, at age 12, she became fascinated with chemical elements after reading Rand’s Medical Chemistry, a standard textbook that she checked out of the Philadelphia Mercantile Library for some light summer reading. She asked the headmistress of her private girl’s school to add chemistry to the curriculum, but her request was angrily rejected. Pennington’s headmistress did not believe that scientific study was appropriate for young women.

Undiscouraged, Pennington enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania when she turned 18. UPenn did admit women to some programs at that time, but members of its board of trustees opposed awarding them degrees. So instead of earning a diploma when she finished her coursework three years later, she received a “certificate of proficiency” in chemistry, biology, bacteriology, and zoology. Yet Pennington’s professors—particularly Edgar Fahs Smith, head of the chemistry laboratory and an advocate of education for women—were so impressed with her abilities that they accepted her into the PhD program without a degree.

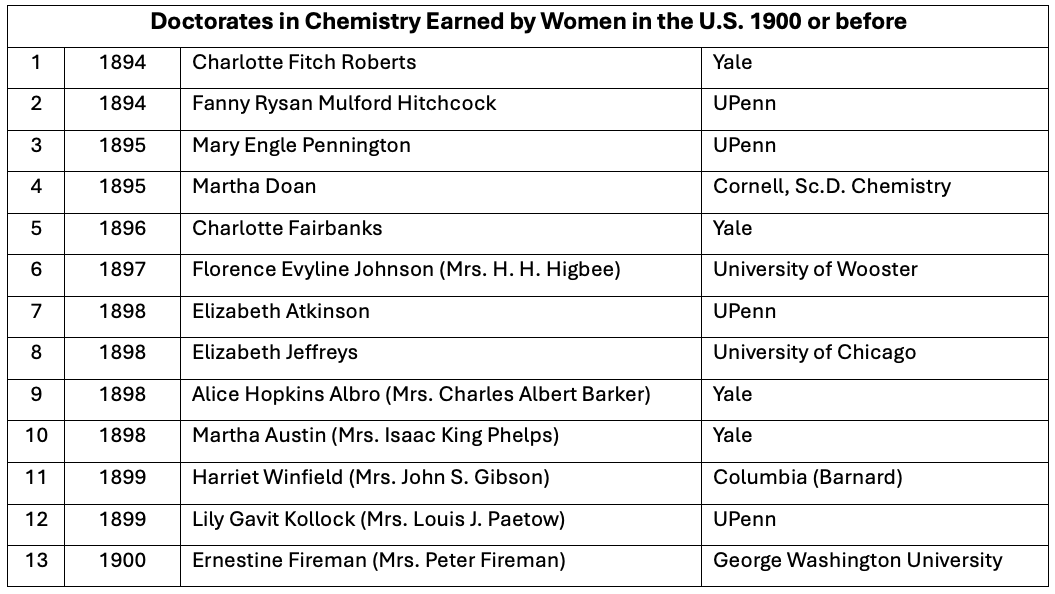

She completed her dissertation on the “Derivatives of Columbium and Tantalum” in 1895, becoming one of only 12 women to earn a chemistry PhD in the United States before 1900. Over the next three years, Pennington held fellowships in chemical botany at Penn and biochemistry at Yale. She published on physiological chemistry, specifically concerning the influence of color on plant growth. She earned membership in the American Chemical Society in 1894, just the third woman to enter that professional organization.

LEARN MORE

This table only includes doctorates awarded by U.S. institutions. The first American woman to earn a PhD in chemistry was Rachel Holloway Lloyd, who received her degree from the University of Zurich in 1887.

Source: Eells, Walter Crosby. “Earned Doctorates for Women in the Nineteenth Century.” AAUP Bulletin, vol. 42, no. 4, 1956, pp. 644–51. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/40222081. Accessed December 18, 2024.

These credentials would have made it easy for Pennington’s male colleagues to find a job in an industrial research lab, a major university, or medical school. But the positions open to women chemists in the U.S. at this time were limited: they could become assistants in male-supervised laboratories, teach home economics, where laboratory research was often secondary to teachers’ training, or pursue nutritional science at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

But Pennington wanted to continue doing laboratory research, so she created a new career path. From 1898 to 1906, she taught physiological chemistry and ran the laboratory at the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia. In 1898 she also cofounded a subscription laboratory business, the Philadelphia Clinical Laboratory Corporation (PCLC). For an annual $50 fee, the PCLC ran bacteriological and chemical analyses for area doctors who were newly aware of bacteriology but lacked the facilities and expertise to run their own diagnostic tests. The lab soon had more than 400 subscribers, including the City of Philadelphia, which hired her to investigate and regulate the city’s often contaminated milk supply. Thus began Pennington’s decades-long career in food safety.

Food Safety and the Progressive Era

Pennington entered public service when reform movements were sweeping across the United States. These sought to address a wide range of social, political, health, and environmental problems created by the nation’s rapid industrialization and urbanization in the decades before World War I. Attracted by a booming manufacturing sector, as well as service jobs, millions of migrants and immigrants poured into cities, where overcrowded housing, inadequate sanitation, disease outbreaks, and contaminated food were major concerns.

Much of the urban food supply now had to travel long distances. Canning corporations like Campbell’s and Heinz tried to claim the growing urban market in preserved foods, while meatpacking firms like Armour, Swift, Cudahy, and Morris organized the transport of “fresh” beef and pork. Despite the efforts of Harvey Wiley, head of the USDA’s Bureau of Chemistry and the nation’s leading food safety advocate, these corporations evaded national regulations. This changed when Upton Sinclair published The Jungle in 1906, a best-selling novel that exposed the horrific conditions of the meatpacking industry. The landmark federal Meat Inspection and Food and Drug Acts were passed that same year, aiming to protect consumers from unsafe products.

Wiley offered Pennington leadership of the USDA’s Food Research Laboratory in 1907, with the task of developing new national standards. This made her the USDA’s only female lab chief and the federal government’s highest paid woman at the time. She took the required civil service exam, a tool that was designed to regulate and improve government services. Significantly, Wiley registered her under the name “M. E. Pennington,” masking her gender. When she scored highest among all the test-takers in that session, the Civil Service recommended her for the job. Later, when her sex was discovered, members of the Civil Service tried to rescind the offer. Wiley intervened to ensure that Pennington took the job.

The Chicken and the Egg

Pennington set to work on the nation’s poultry- and egg-supply systems, which had spread thousands of miles in just a few decades. Customers, she noted, expected to be able to buy poultry and eggs year-round, whereas before, they only got “eggs in the spring, chickens in the fall, and turkeys in winter.” For the next four years, Pennington and her staff traveled by train to the Mississippi and Missouri valleys, the main chicken- and egg-producing districts of the country.

They surveyed and recorded every detail—from butchering to cleaning—and found that chickens and eggs were often “unfit when they went into storage” due to a lack of sanitization. Those same damaged goods often spent days or even weeks in poorly refrigerated railroad cars and urban warehouses before arriving at stores, where they might sit for several more days. These practices often led to bacterial contamination, public suspicion of refrigerated goods, and millions of lost dollars in wasted food.

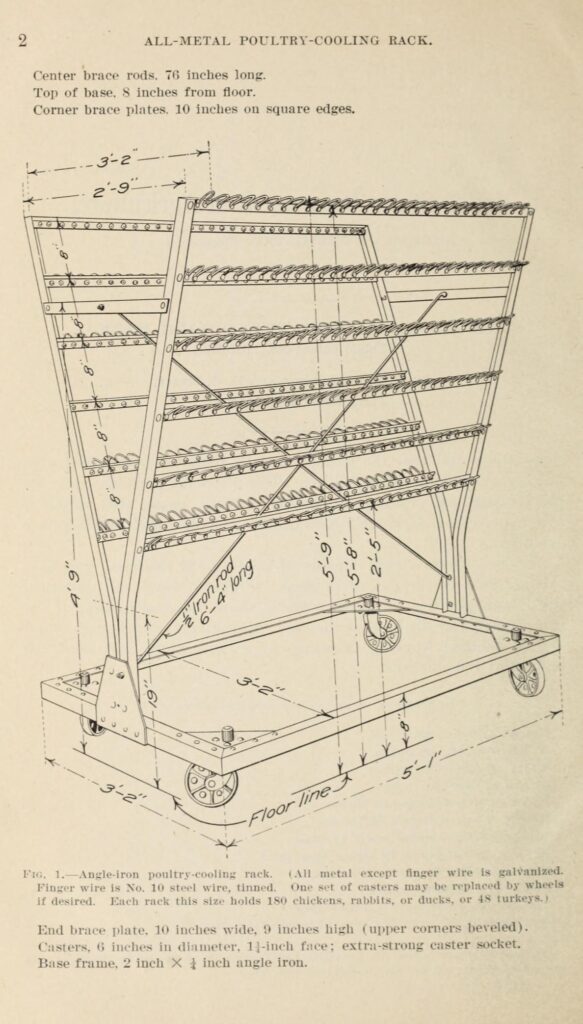

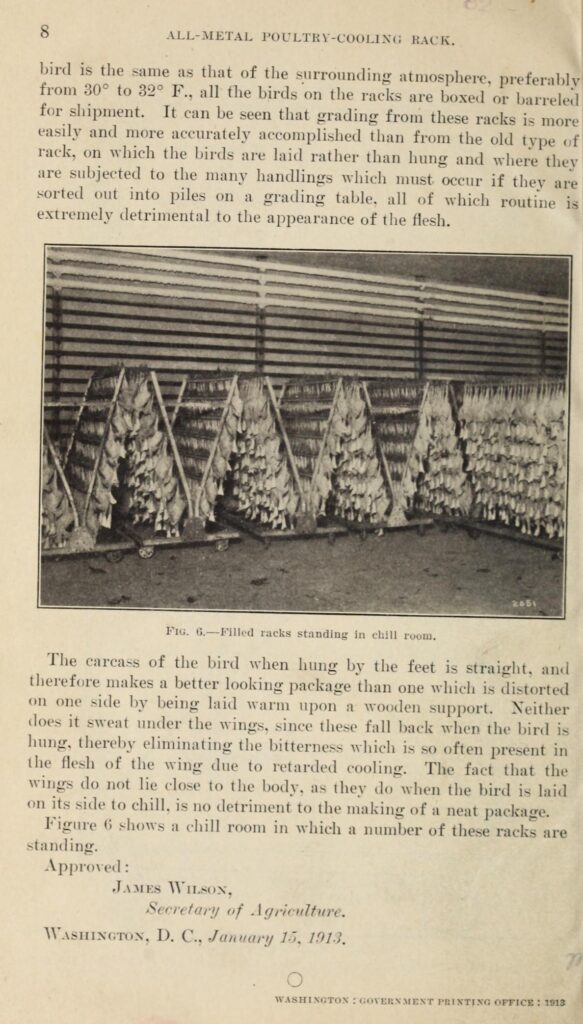

To address the concerns of businesses and consumers, Pennington personally tested new handling techniques and technologies. She slaughtered and packed thousands of chickens herself, developing sanitary methods like fast freezing. She even designed and patented a specialized cooling rack for that purpose. She and her team publicized their findings widely through government bulletins and speeches to industry groups to advocate for those changes. Though some were skeptical of her cold-chain standards at first, America’s entry into World War I proved decisive in their implementation.

Left: Illustration of Mary Engle Pennington’s all-metal poultry-cooling rack, patented March 19, 1912; Right: Chill room with filled racks.

“Reefers,” War, and Frozen Fish

“We are at war . . . we need food. . . and that food must be saved,” Pennington said in an October 1917 address to the St. Louis Railway Club. She had by this time been assigned to Herbert Hoover’s War Food Administration (WFA), an agency organized to maximize food production and conservation in support of the war effort. Pennington joined a team of 27 men at the WFA—they called themselves the “imperishables”—charged with testing the storage and cooling systems of the nation’s 40,000 refrigerated railcars. Using electric thermometers positioned at several levels in the cars, they took constant temperature readings as the trains moved from coast to coast. They also experimented with different types of loading racks, ice bunkers, and air circulation systems to cool the cars evenly. Pennington herself completed 500 of these expeditions over the course of just two years, sleeping in cabooses on railroad sidings and, she later recalled, “talking over crops with farmers at crossings.”

Her team found that less than 10% of “refrigerated” railcars (or “reefers” as they were known) were sufficiently cold. Many were poorly insulated with just paper or air. In response, Pennington issued guidelines for how a well-designed “reefer” should be built. Because the U.S. government had temporarily taken control of the nation’s railroads during the war, entire fleets were built to her specifications.

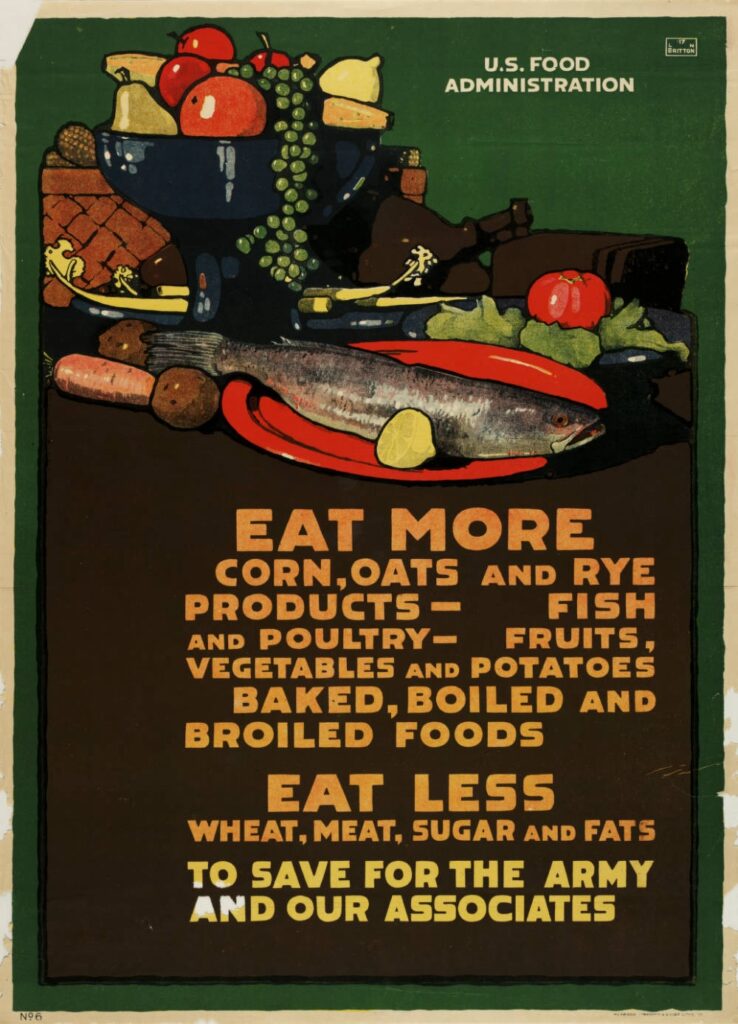

Pennington also played a leading role in war-time food conservation efforts. She encouraged Americans to substitute poultry, eggs, and frozen fish for the beef and pork that was set aside for soldiers. Pennington’s lab had been tasked with setting standards for the emergent frozen-fish industry even before the war. Long before frozen foods became commonplace in U.S. grocery stores, Pennington was pointing out that “all sorts of berries, fruits and vegetables can be frozen and kept for many months” and retain their taste if frozen properly.

Last Chapter and Legacies

After 11 years with the USDA, Pennington left government service for the private sector in 1919. Her reasons are not entirely clear, but she was interested in working cooperatively with companies to promote better food safety standards and practices. She recognized that it was good for businesses, saving them money and avoiding negative publicity, and was morally imperative, ensuring a healthy food supply for ordinary people.

This cooperative approach and many years of government experience, along with her skills as a scientist and refrigeration specialist, led to a very successful three-decades-long second career (1919–1952) as an industry consultant specializing in refrigerated food transport, cold storage, and home refrigeration, the final link in the cold chain.

Pennington’s achievements in these male-dominated fields, combined with her established reputation as a professional chemist, made her something of a popular icon for aspiring women scientists and engineers in the last decades of her life. A profile in the November 1930 issue of the Woman’s Journal, for example, called her “America’s foremost women chemist,” and she was regularly featured in articles outlining careers for women in chemistry and engineering. In 1940 she became only the second woman to win the Garvan Medal from the American Chemical Society, a recognition of “distinguished service to chemistry by women chemists.” In 1947 the American Association of Refrigerating Engineers made her a “fellow” (she had become the first female member of that organization in 1920).

Though she would likely have welcomed the recognition from her colleagues in engineering, she might not have wanted to be held up as an example for women in general. Pennington did not like public attention, and she had spent her entire professional career ignoring gender barriers as she encountered them. Once asked about her position on the women’s suffrage issue (1913), Pennington responded: “Chickens in cold storage are more interesting than women’s suffrage. I have no sympathy with the women’s movement as such. Ability always precedes success and women with ability will achieve success as citizens.”

Glossary of Terms

Perishable

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines perishable foods as “those likely to spoil, decay, or become unsafe to consume if not kept refrigerated at 40°F or below, or frozen at 0°F or below.”

Back >>

Physiological chemistry

A branch of science concerned with the chemistry of function in living organisms.

Back >>

Industrialization and urbanization

A move away from agrarian life characterized by the use of machines and non-human energy sources in densely populated spaces.

Back >>

Women’s suffrage

A complex historical movement dedicated to women’s voting rights.

Back >>

Further Reading

Heggie, Barbara. “Profiles: Ice Woman.” The New Yorker, September 6, 1941. 23-26, 29-30.

Rees, Jonathan. Refrigeration Nation: A History of Ice, Appliances and Enterprise in America, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Robinson, Lisa Mae. “Establishing the Cold Chain: The Work of the United States Food Research Laboratory, 1907–1919.” Journal of Agricultural & Food Information, 7(1) (2006): 19–37.

Nicola Twilley. Frostbite: How Refrigeration Changed Our Food, Our Planet, and Ourselves. Penguin-Random House, 2024.

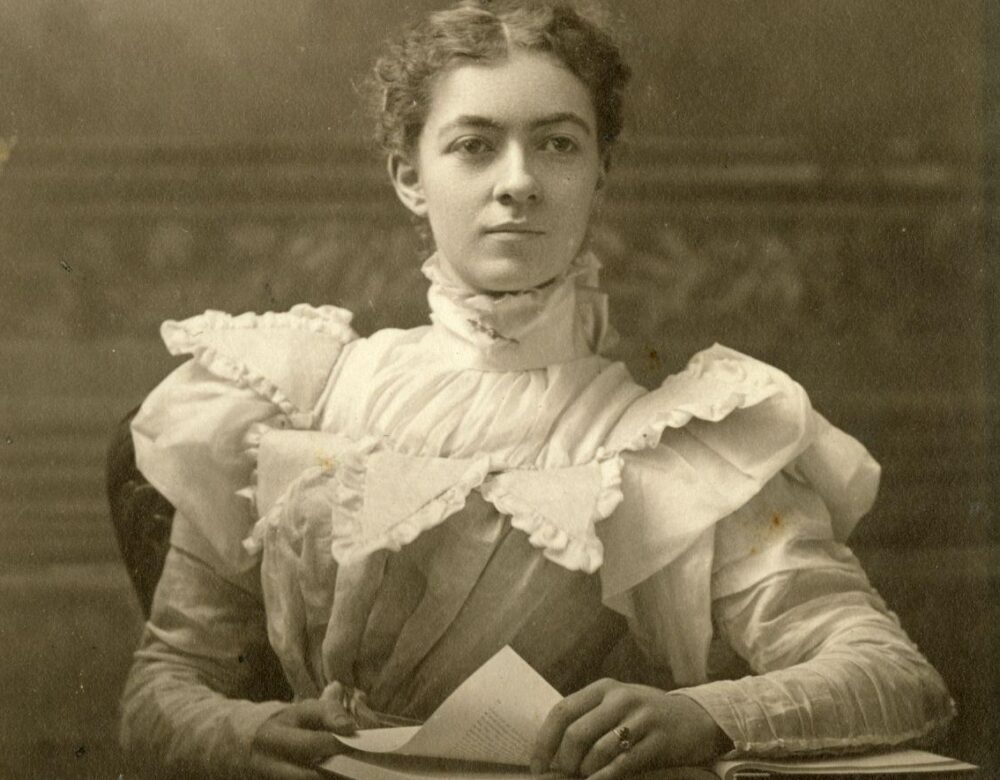

Featured image: Undated photo of Mary Engle Pennington as a young woman, likely from her time at the UPenn.

University of Pennsylvania Archives