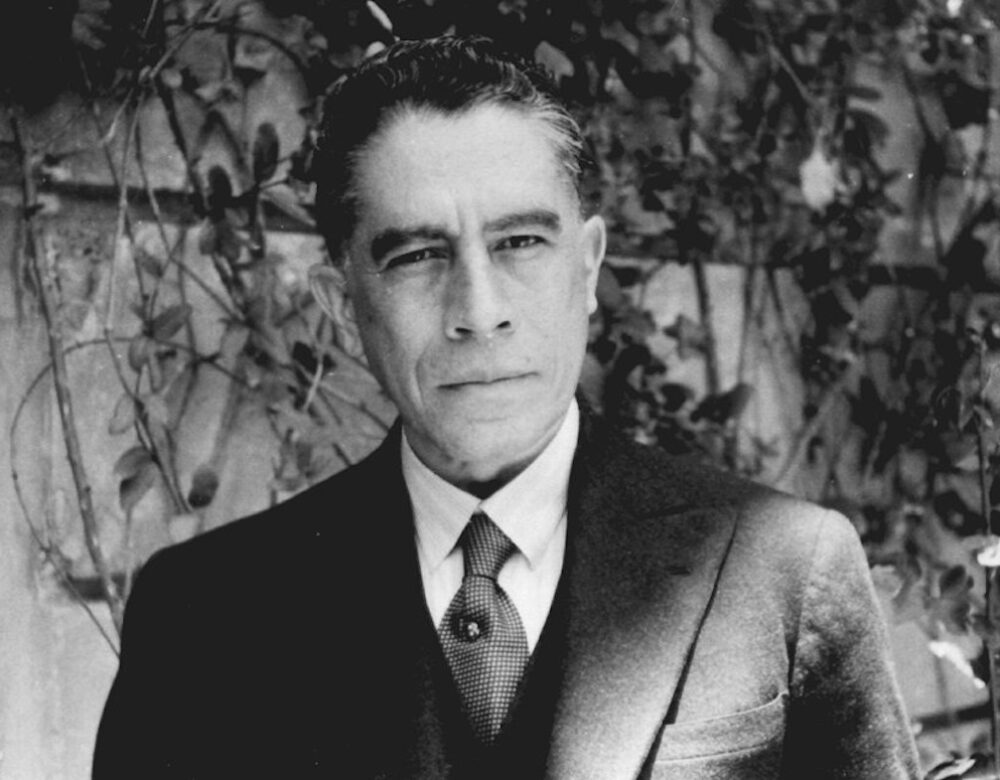

Isaac Ochoterena

Jacobo Isaac Ochoterena y Mendieta was a self-taught scientist who created new programs for biology education and research in 20th-century Mexico.

Jacobo Isaac Ochoterena y Mendieta (1895–1950) developed new educational standards, professional organizations, and academic programs for scientific research in Mexico during the early 20th century. Working through the period of the Mexican Revolution, he prioritized the collection of native plants and animals and aligned biology with medicine, which was already an established profession. He had a powerful influence on the training of the first generation of academic biologists in Mexico, establishing scientific traditions focused on natural resources and public health.

A Self-Taught Scientist

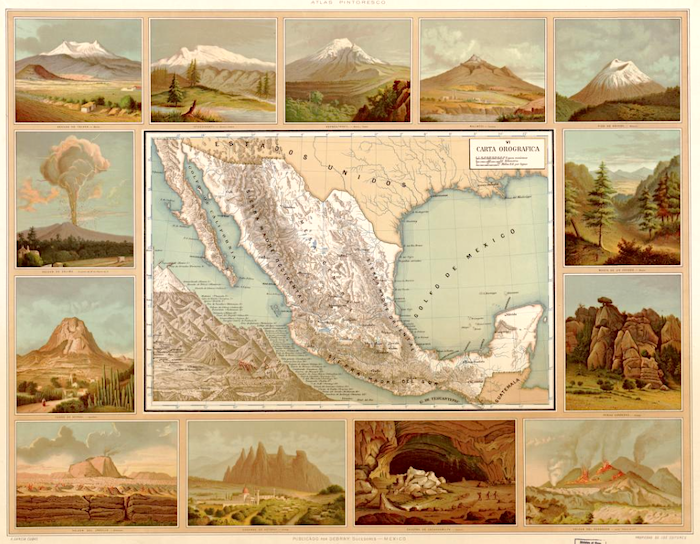

Ochoterena’s passion for science led him to independent study in several branches of the life sciences. Born at the foot of the Popocatépetl volcano in 1885, Ochoterena attended elementary school in Atlixco, his hometown, before moving to Mexico City to continue high school at the National Preparatory School of San Ildefonso.

The death of his father in 1901, however, prevented him from completing the degree. He continued to study natural history, microscopic anatomy (or histology), and geography on his own. In 1906 he took an examination at the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts to be accredited as an elementary school teacher. Ochoterena successfully obtained the permit, becoming a self-taught educator.

Teaching Others

Ochoterena began teaching young students in the south of Puebla, his native state, before moving to Durango. Here, he became headmaster of the school in Ciudad Lerdo and an inspector of public instruction, jobs he held until 1913. In his role as inspector—which involved making sure that schools were upholding moral, political, and legal standards—Ochoterena had the opportunity to travel widely, deepening his biological understanding of this dry region. In 1910 he created the Universal Scientific Alliance, an organization that published a newsletter to share new scientific research widely. The Alliance was supported by the government of the state of Durango, which hoped to make technical knowledge more accessible to its people.

Two years later, he married Carmén Sarabia Castillón, sister of the famous aviator Francisco Sarabia. In 1914 they moved to San Luis Potosí in central Mexico. There, he became the state’s general director of education and a research professor in histology, botany, anthropology, and geography. His early scientific publications were on these subjects. They included a 1909 study of the effect of phosphorus on seed germination, a 1910 paper on the scorpions of Durango, another in 1912 on desert plants, and a technical overview of the microscope published in 1914.

LEARN MORE

This is an early example of the Universal Scientific Alliance’s Boletin del Comite Regional del Estado de Durango. The organization’s Latin motto, “Corpore Diversi sed Mentis Lumine Fratres” [“Diverse bodies, but brothers in mental illumination”], was also used by the Paris Society of Ethnography. What do you think this motto means? Why do you think the Alliance adopted it? What might it have meant to Ochoterena?

In 1916 Ochoterena moved to Mexico City, where he became director of the Vegetal Biology Section of the Direction of Biological Studies, then part of the country’s Ministry of Agriculture. He held the position until 1918. During this period, he was invited to teach at the Military Medical School where he created courses in histology and embryology. To recognize this accomplishment, he was given the high military rank of lieutenant colonel. Three years later, Ochoterena co-founded the Mexican Biology Society. The Society, in turn, established the Mexican Journal of Biology so that researchers could share their work.

Ochoterena became the head of biology and curator of the natural history collections at the National Preparatory School in 1921, the same institution he had to leave as a teenager. Several young biologists came through his classroom, and Ochoterena passed his commitments to natural resources and public health on to them. Helia Bravo-Hollis, for instance, went on to lead the study of cacti both in Mexico and around the world; Eduardo Caballero y Caballero made a name for himself researching parasites. Bravo-Hollis affectionately referred to Ochoterena as her “wise professor” because, according to her, he could maintain a fluent conversation on any subject with anyone.

Revolutionizing Biology

By 1929 several political groups with roots in the Mexican Revolution came together to form the National Revolutionary Party [Partido Nacional Revolucionario]. Their goal was to create stability in the wake of the assassination of president-elect Álvaro Obregón. They were successful, eventually ruling the country as the Institutional Revolutionary Party [Partido Revolucionario Institucional] until 2000.

To achieve stability, Party leadership strengthened ties with the Catholic Church, which caused tension at the National University of Mexico. To relieve this tension, the University was granted autonomy from the government and was renamed the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). In this complex process, Ochoterena was named director of UNAM’s Institute of Biology, which he led for 17 years. Under his leadership, the Institute of Biology sought favor from the medical community, which had come out of the national conflict with newfound power and authority.

Thus, the Institute under Ochoterena’s leadership focused on collecting, classifying, and carefully describing specimens, many of which had bearing on health concerns of the day. When the Faculty of Sciences was created in 1939, he became head of the Biology Department at UNAM, further centralizing his control of biological research and education in Mexico.

LEARN MORE

Look at the images in Ochoterena’s biology textbook, Lecciones de Biologia. What do you notice? Is there anything here you would expect to find in a more recent biology textbook? What content do you think would have changed?

In 1940 Ochoterena was awarded an honorary doctorate by UNAM, and a year later, he was appointed general director of Higher Education and Scientific Research, as well as head of the Histology Section of the Institute of Hygiene at the Ministry of Health and Assistance. Not long after, in 1943, he became one of the founding members of the National College, an institute formed with the purpose of bringing together leaders in the sciences and humanities to promote new knowledge in Mexico.

Ochoterena lived a busy life that led to the publication of more than 230 scientific research papers on subjects ranging from botany and geography, to histology and embryology. He also wrote books on biological education. He was a member of research groups dedicated to biology, geography, statistics, botany, and medicine. Many of these were based outside of Mexico—from Bolivia’s International Society for Scientific Research, to the Soviet Union’s Society of Applied Botany and the U.S. Society of Plant Taxonomists.

Ochoterena’s efforts to connect with international organizations would often result in a strengthening of diplomatic bonds between the countries involved. This type of interaction helped researchers from all over the world exchange biological specimens, knowledge, and techniques. Ochoterena often, then, passed these benefits on to his students.

Isaac Ochoterena died in Mexico City on April 11, 1950. His remains rest in the Rotunda of Illustrious Characters of the Panteón Civil de Dolores, a testament to the national significance of his scientific work.

Glossary of Terms

Mexican Revolution

This was a complex civil war from 1910 through 1920 that resulted in the end of a dictatorship and the creation of a constitutional republic.

Back to top

Natural History

A branch of biology that uses observational methods to study plants, animals, and other organisms.

Back to top

Histology

The study of the microscopic structures of the tissues and organs.

Back to top

Embryology

The study of how embryos and fetuses develop.

Back to top

Further Reading

(2021), Isaac Ochoterena, El Colegio Nacional, from: https://colnal.mx/integrantes/isaac-ochoterena/.

Ledesma-Mateos, Ismael, Ana Barahona (2003), “The Institutionalization of Biology in Mexico in the Early 20th Century. The Conflict between Alfonso Luis Herrera (1868-1942) and Isaac Ochoterena (1885-1950),” Journal of the History of Biology, 36(2): 285-307.

Ochoterena, Isaac. “The Origin and Evolution of the Interstitial Cells and of the Ovary and the Significance of the Different Internal Secretions of the Ovary,” Endocrinology 4 (1920): 541-546.

You might also like

DIGITAL EXHIBITIONS

Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Poisonous Plants

Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories from 1887 to 1927 open a window to the history of medicine and empire.

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

Helia Bravo-Hollis

One of the most prolific botanists of the 20th century, Bravo-Hollis was the first woman to receive an advanced degree in biology in Mexico.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Forests of the Future

Modern agricultural practices are unsustainable. Is tree farming the answer?