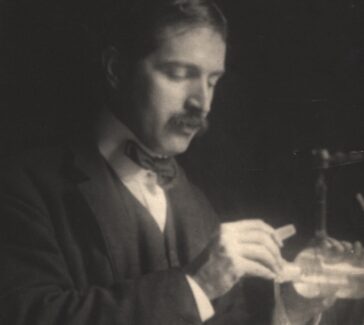

Helia Bravo-Hollis

One of the most prolific botanists of the 20th century, Bravo-Hollis was the first woman to receive an advanced degree in biology in Mexico.

At a time when few Mexican women could participate in scientific research, Helia Bravo-Hollis (1901–2001) forged a new professional pathway. Over the course of her career, she classified more than 700 species of cacti native to Mexico, published nearly 170 scientific papers, contributed to the description of 60 existing classifications, and authored 3 books. She also directed the Herbarium of the Institute of Biology in Mexico City and helped to establish the Botanical Garden at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

An Early Love of Nature

Helia Bravo-Hollis was born in 1901 in Villa de Mixcoac, then on the outskirts of Mexico City. Undeveloped nature surrounded the town, and Bravo-Hollis’s family frequently explored nearby pine forests and rivers. It was on these trips that she developed a love of the natural world. She also won accolades and prizes as a young student for her grades, including a congratulatory letter signed by Mexican President Porfirio Díaz in 1909 and several books about nature. She later recalled being moved to study biology by the pictures in those books.

But turbulent times brought instability to Bravo-Hollis’s life. In November of 1910, an armed uprising led by revolutionary leader Francisco I. Madero brought an end to Díaz’s dictatorial regime. Revolutionaries called for universal voting rights, the prohibition of reelection, and a new constitutional government. Madero became the leader of that government a year later as Mexico’s 37th president, but he was assassinated in February 1913. Army General Victoriano Huerta briefly took his place as the country entered into civil war. During the conflict, a firing squad assassinated Bravo-Hollis’s father for his loyalty to Madero.

Biology Student

Bravo-Hollis’s first exposure to formal scientific research came a few years later at the prestigious National Preparatory School of San Ildefonso. Here, she walked among murals being painted by Diego Rivera and Clemente Orosco, with classmates including the painter Frida Kahlo and poet Octavio Paz.

Her teacher, Isaac Ochoterena, was known for encouraging his best students to undertake hands-on research in the life sciences. Looking for tiny, single-celled organisms called protozoans under a microscope, Bravo-Hollis later recalled, was the moment she became a biologist. While still a student, she presented the results of related studies on Hydatina senta, a kind of sea snail, at the Antonio Alzate Society, the most important scientific research center in the country at that time.

In 1923 Bravo-Hollis entered the National University of Mexico—today known as the Universidad Autónoma de México (UNAM). Her family wanted her to study medicine, but when the university began offering a degree in biology a year later, she immediately requested a transfer, making her the first woman in Mexico to study biology at a university.

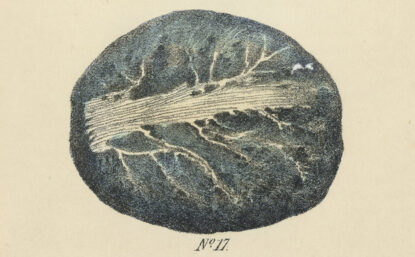

Ochoterena, who continued to mentor her research, encouraged her to pivot from zoology to botany after 1925. He invited her to complete a survey of Mexican cacti, thinking this would promote national interests. Bravo-Hollis earned her master’s degree in biological sciences in 1931 with a thesis titled “Contribuciones al conocimiento de las cactáceas de Tehuacán” (“Contributions to Knowledge of the Cacti of Tehuacán”).

LEARN MORE

Compare the path Bravo-Hollis took in her scientific career with that of another woman in the Scientific Biographies. What similarities and differences do you observe? Would you say the political conditions in Mexico during the 1920s and 1930s helped or hurt her professional ambitions?

“To work and work for biology”

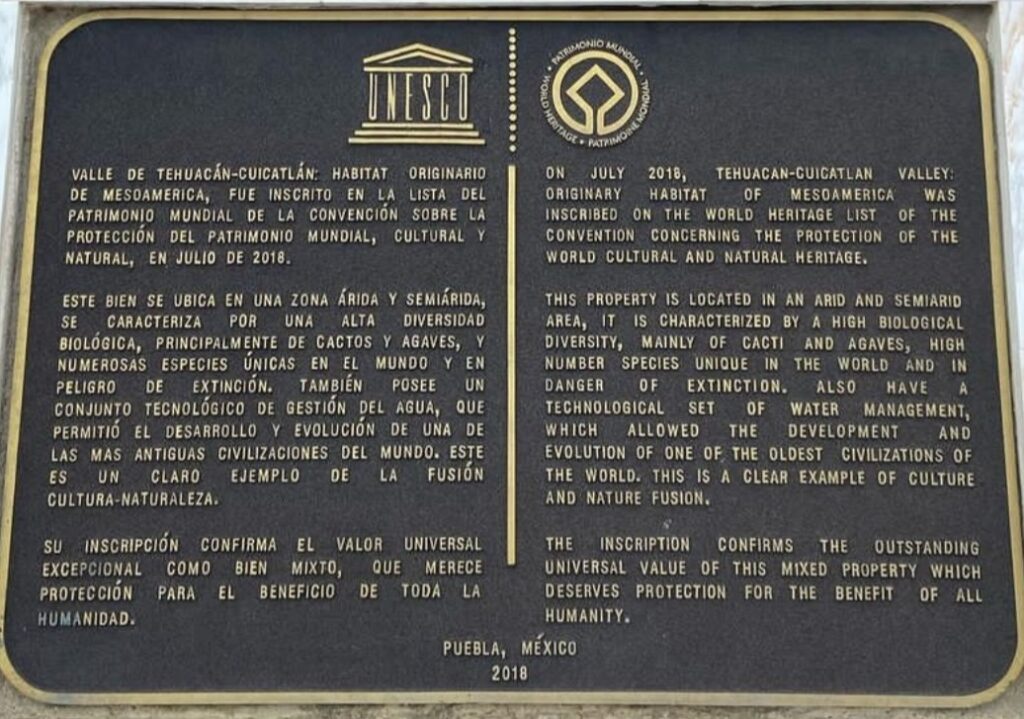

In 1929 Bravo-Hollis’s former teacher, Isaac Ochoterena, became director of UNAM’s Instituto de Biologia (Institute of Biology). He asked “Teacher Bravo,” as she came to be known, to direct the Herbario Nacional de México (Mexican National Herbarium) and to study the cacti of Mexico. This ignited her passion for the plants. She traveled the country collecting specimens and photographs of cacti, mainly from the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán region in Puebla, today a protected area with a botanical garden that bears her name. With a knife in hand and a long-skirted tailored suit, she was seen crossing fields and deserts in the early years of this research.

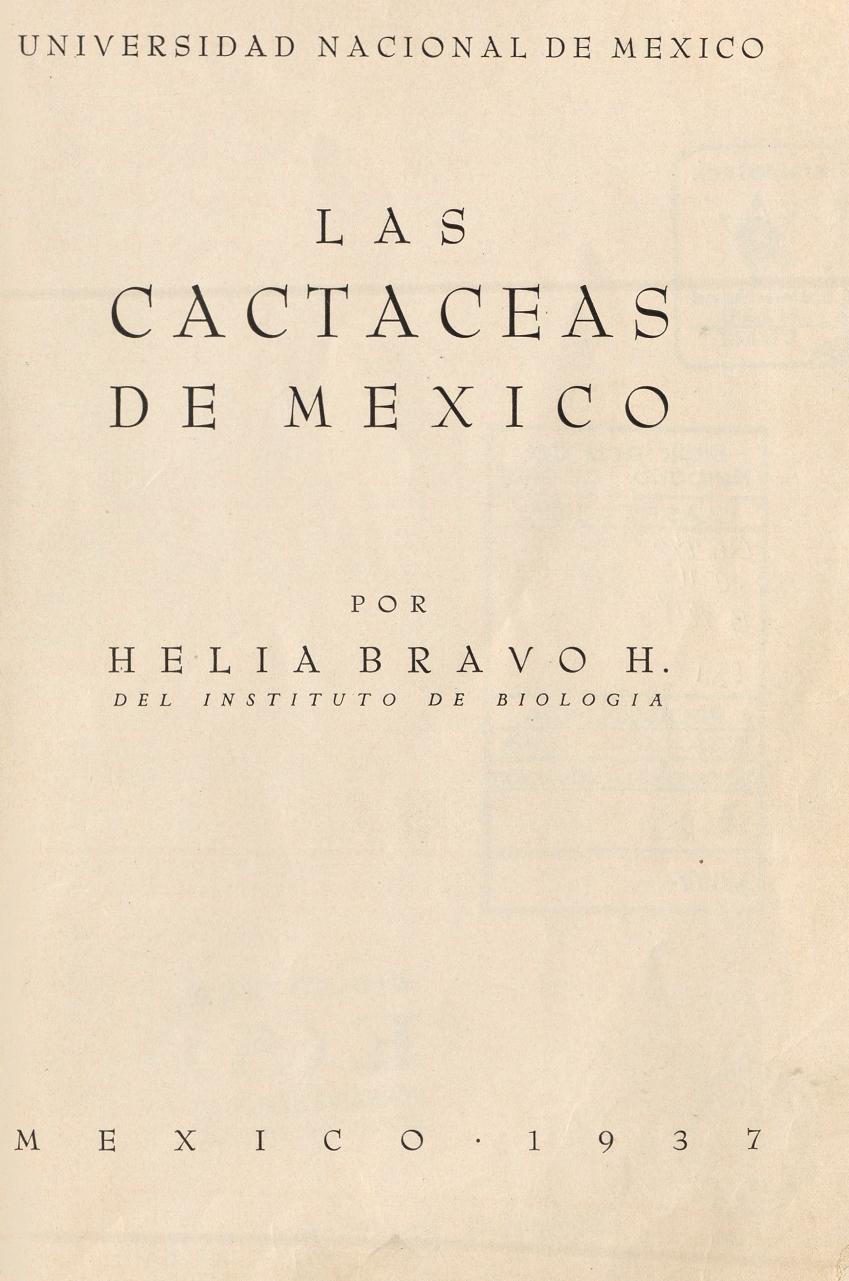

She published these studies in Las Cactaceas de México (The Cacti of Mexico), which brought the country’s cacti together in one place. The book was very popular with a wide readership and quickly sold out. Bravo-Hollis also mentored many important researchers. Among them was her sister, Margarita, who would become a pioneer scientist in her own right, specializing in helminthology, or the study of parasitic worms.

LEARN MORE

In Las Cactaceas de México, Bravo-Hollis writes lovingly of her country and its cacti:

“To be able to appreciate such an astonishing number of forms, it is necessary to travel through the mountains between Tehuacan and Zapotitlan, in the State of Puebla, in whose succession of limestone mountain ranges, extremely dry and almost devoid of herbaceous vegetation, forests of columnar organs have been formed, gigantic, simple and tall, provided at the tip with a plume of silvery manes that shine in the sun…”

What do you make of Bravo-Hollis’s emotional response to her research subject? Is it surprising or not, and why?

Queen of Cacti

In 1937 Ochoterena advised Bravo-Hollis to devote herself to teaching, saying that she had nothing more to learn from him or the Institute of Biology. With that goal in mind, she resigned from her researcher position. But instead of pursing a teaching career, she married José Clemente Robles, a former classmate and renowned neurosurgeon. During her 13-year marriage, Bravo-Hollis dropped out of academic life.

After her divorce in 1950, her plants immediately welcomed her back. She became the head of the biology department at the National Polytechnic Institute and co-founded the Mexican Society of Cactology in 1951 with renowned cacti researchers Jorge Meyrán, Eizi Matuda, Dudley Gold, and Sánchez Mejorada. “These two events excited me so much that I didn’t have the opportunity to lament my divorce,” she later said. Like the cacti she adored, she was often described as tenacious, resilient, and steadfast.

Bravo-Hollis later returned to UNAM, where she and other members of the Mexican Society of Cactology founded the university’s Botanical Garden in 1961. She was the first director of this living museum, which now houses approximately 12.7% of all endangered species of Mexican cacti. She only retired at the age of 90 in 1991 because of a severe case of arthritis.

“My life’s motive was biology and cacti,” Bravo-Hollis said in a 2001 interview. “I dedicated almost…100 years to my precious science. Thanks to it we know the nature of which we are part.” Her career was long and not without rough patches, but despite adverse conditions, she became one of the most prominent botanists of her time. She was awarded the Cactus d’Or by the International Organization for Succulent Plant Study in 1980 and she received an honorary doctorate from UNAM in 1985.

Helia Bravo-Hollis passed away in Mexico City in 2001. The secret to her longevity, she said, was “to work and work for biology.”

Further Reading

Aguilar-Rocha, M, (2019), A lifetime among Cacti: Helia Bravo-Hollis, Biodiversity Heritage Library Blog, from: https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2019/03/helia-bravo-hollis.html

Biodiversidad Mexicana, (2022), Helia Bravo-Hollis, Biodiversidad Mexicana, from: https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/biodiversidad/curiosos/helia-bravo-hollis

Bravo-Hollis, H (2004), Helia Bravo-Hollis. Memorias de una vida y una profesión, DGDC e IBN, UNAM.

Salcedo C, (2001), Helia Bravo, ¿Cómo ves?, from: https://www.comoves.unam.mx/numeros/quienes/34

Library of Congress, “The Mexican Revolution and the United States in the Collections of the Library of Congress,” from: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/mexican-revolution-and-the-united-states/index.html

Featured image: Portrait of Helia Bravo-Hollis, 2001, from Cactus People Histories: Who Is Helia Bravo-Hollis?, The Cactus Explorer, March 2019.

You might also like

STORIES BY TOPIC

Women Do Science, Too

Although women have often faced barriers to participating in science, science is definitely women’s work.

DIGITAL EXHIBITIONS

Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Poisonous Plants

Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories from 1887 to 1927 open a window to the history of medicine and empire.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Forests of the Future

Modern agricultural practices are unsustainable. Is tree farming the answer?