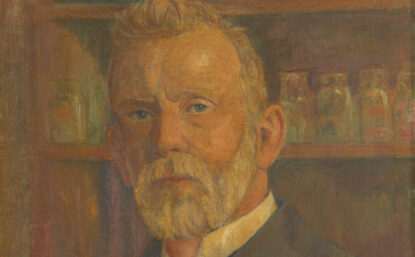

Fanny Angelina Hesse

Hesse changed medicine and the life sciences when she introduced agar, a jelly derived from seaweed, into laboratory research.

Fanny Angelina Hesse (1850–1934) was educated to be an upper-class wife, not a scientist. But her knowledge of cooking and her scientific acumen proved essential to the development of the modern life sciences. She suggested using agar, a jellying agent used in Southeast Asian cuisine, instead of gelatin to obtain and study colonies of microbes. Today, agar is used in laboratories around the world.

Youth and Family Life

Fanny Angelina was born in New York City in 1850 and grew up in Kearny, New Jersey. Her parents had just emigrated to the U.S. a few years before her birth. Her father, Henry (Hinrich) Gottfried Eilshemius, was a wealthy merchant of Dutch and German origins; her mother, Cécile, was from the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Fanny Angelina, or “Lina” as she was called by her family, was the eldest of ten siblings, though five died in childhood. Her family lived on an estate called Laurel Hill Manor near the Passaic River. She learned how to cook from her mother and the servants at Laurel Hill, an education that would later prove decisive in the lab.

She did not receive formal scientific training. Instead, her parents sent her to finishing school in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, at age 15. There she studied home economics and French, as was common for young women from wealthy families at the time.

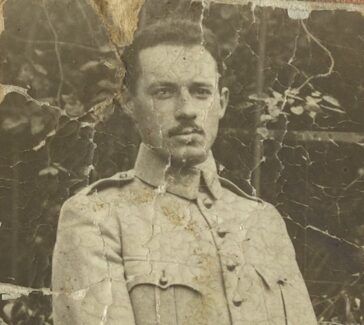

At age 22, Fanny Angelina met a German physician named Walther Hesse (1846–1911). Walther had come to New York by boat, working as a ship’s physician. Following a brief courtship, the newlywed couple settled down near Dresden, Germany, where Walther began work as a district doctor serving over 80 towns. As part of this work, he studied public health and was responsible for vaccinating residents against smallpox. These were his entry points into the field of microbiology.

Contribution to “Koch’s Plating Technique”

In the winter of 1880–1881, the Hesses moved to Berlin so that Walther could join the laboratory of bacteriologist Robert Koch. Koch was researching the cause of tuberculosis, a deadly infection of the lungs.

Initially, Walther struggled to study airborne microbes in the lab. Like Koch, he had been using gelatin, which would turn into liquid at the warmer temperatures needed to grow many disease-causing microbes. Also, inconveniently, several microbes can digest gelatin, turning it into a gooey mess and making it hard to isolate and study them.

During the summer of 1881, once Walther and Fanny Angelina returned home, temperatures soared near Dresden. This made Walther’s attempt to grow microbes on gelatin even harder. Fanny Angelina suggested using agar instead. This substance, which is obtained from red algae (seaweed), forms firmer gels than gelatin.

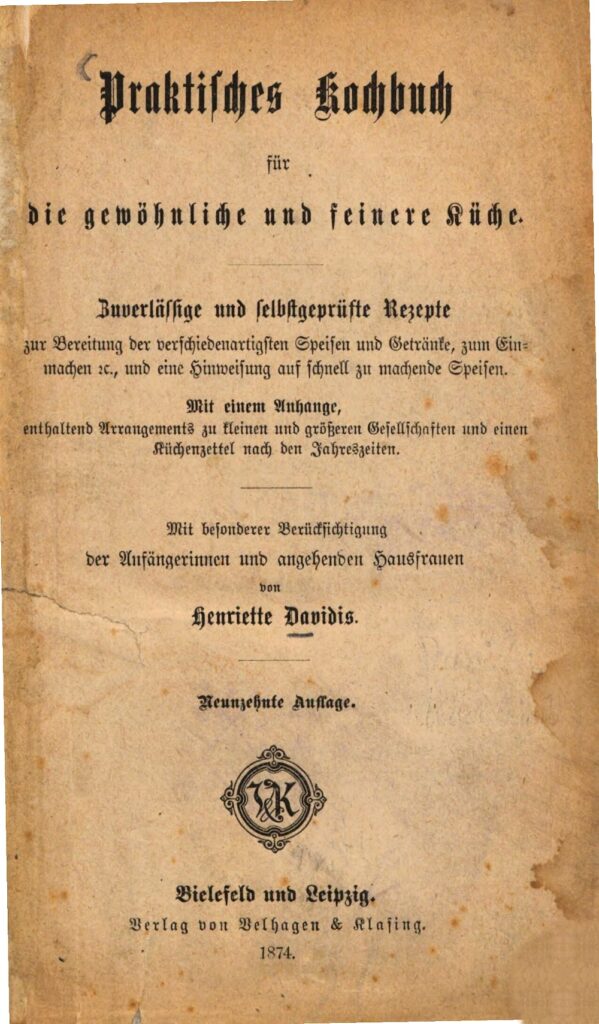

Title page (left) and a page on agar-agar (right) from Praktisches Kochbuch für die gewöhnliche und feinere Küche, a German cookbook by Henriette Davidis, 1874.

Fanny Angelina learned about agar as a child from Dutch neighbors who had moved to the New York area from Java (present-day Indonesia), which was a colony of the Netherlands at the time. In many Southeast Asian regions, “agar-agar” (meaning “jelly” in the Malay language) is used traditionally for jellying foods at warm temperatures. She knew how to use it to set puddings and other desserts in the summer months. She might also have seen agar discussed as a jellying agent in German cookbooks of the period. Henriette Davidis’s 1874 Praktisches Kochbuch für die gewöhnliche und feinere Küche [Practical Cookbook for Ordinary and Fine Cuisine] dedicated an entire chapter to agar, for example.

Fanny Angelina’s training as an upper-class housewife thus transformed laboratory research in the life sciences. The stability of agar at high temperatures, its resistance to digestion by microbes, and the possibility to sterilize and store it as plates in Petri dishes made it easy to grow colonies of microbes for experimental study. As two historians noted in 1939, a few years after Fanny Angelina’s death, “Lesser innovations and discoveries are commemorated with the name of the discoverer.”

LEARN MORE

To study microbes, biologists need to grow and feed them. The procedure is similar to cooking a meal in a kitchen. While cooks prepare a meal, microbiologists prepare a “medium,” a broth rich of nutrients like carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, plus minerals and other trace elements. While cooks feed their guests, microbiologists grow, or “culture,” microbes. Take a look at this 1922 textbook, The Science of Common Things. What words on the page seem to come out of laboratory practice? What words sound like they belong in the kitchen? Why do you associate some words with science and others with cooking? How do you define “science”? How do you define “cooking”? How do these categories relate?

Fanny Angelina and Walther Hesse never published on agar or their contributions to “Koch’s plating technique.” Many of the primary sources documenting their lives were likely destroyed in the bombing of Dresden during World War II. From the small amount of literature about Fanny Angelina Hesse that does exist, she appears to have been a person who rarely spoke about her achievements. But it is important to recognize that her contribution to developing agar-based solid media was already mentioned in textbooks during her life. Few professional scientists can boast such an achievement.

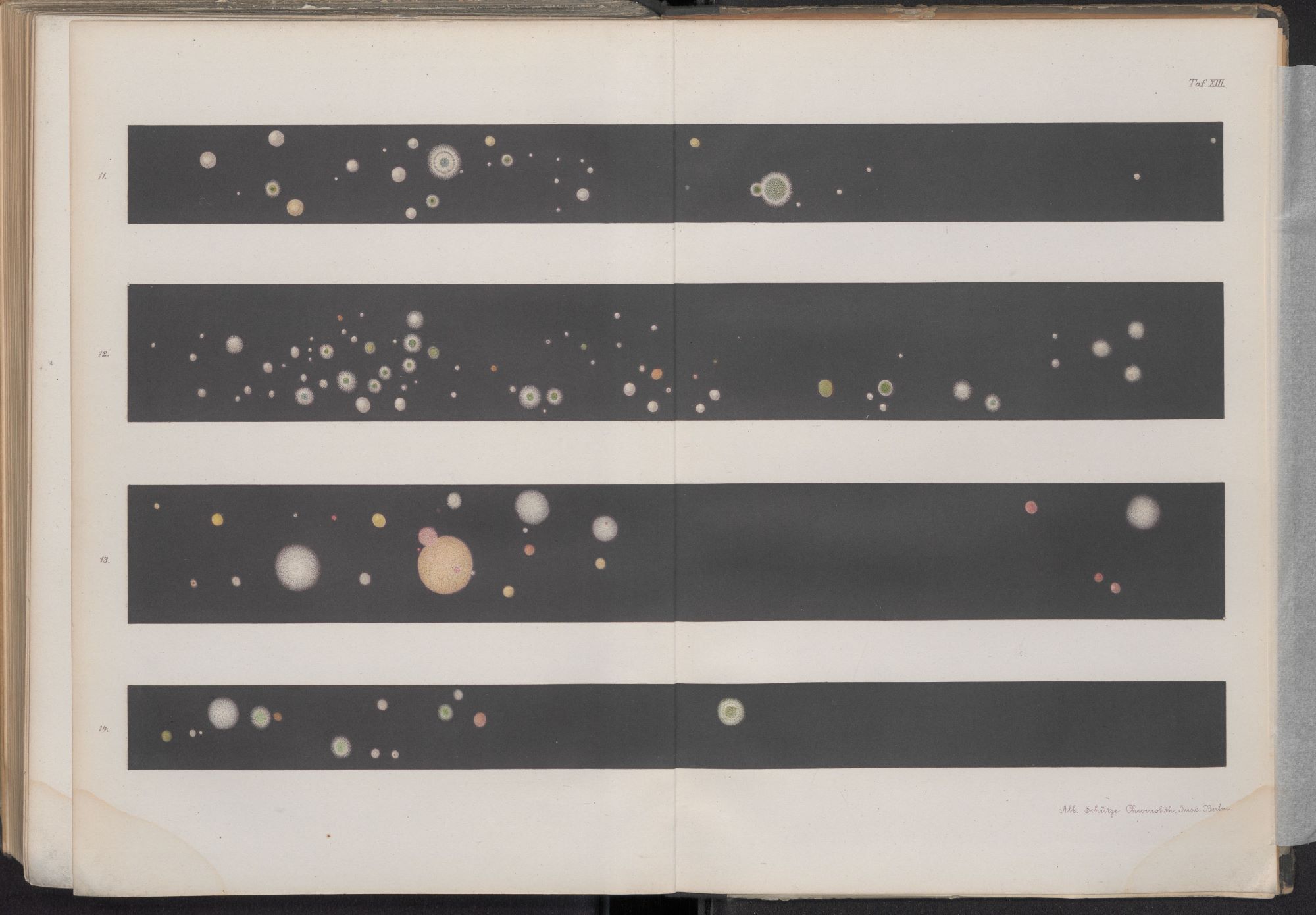

Other Scientific Contributions

Fanny Angelina Hesse’s grandson recalled in 1992 that she worked as a “present-day medical technologist,” though this professional role did not exist in her lifetime. In addition to the suggestion of agar, she created numerous accurate scientific illustrations, some of which have survived to this day. She painted bacterial colonies on solid media making expert use of watercolors and demonstrating a keen understanding of microbiology. These watercolors were published in scientific articles attributed to her husband.

LEARN MORE

In recent years, several initiatives have kept Fanny Angelina Hesse’s memory alive. In 2024 researchers named a new microbe after her, Streptomyces hesseae. There have also been awards dedicated in her name: the “Frau Hesse Award,” which was awarded by the University of Virginia between 1981 and 1996, and the “Fanny Hesse Award” given by the Dutch Microbiological Society (KNVM) since 2024. Currently, a team of scientists and artists led by Corrado Nai are developing a graphic novel about this overlooked chapter in scientific history.

What do you think of these examples of scientific commemoration? Is it important for scientists to look back on their predecessors? Why or why not?

Glossary of Terms

Colony

Groups of microbes growing on a nutrient-rich surface into a pimple-like formation visible to the naked eye.

Back to top

Jellying agent

A substance that thickens a liquid and turns it into a gel. Agar is particularly interesting as a jellying agent because it forms strong (solid) gels.

Back to top

Microbiology

The study of microbes—also called “microorganisms”—like bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea, algae, protists, and parasites. Most, but not all, microorganisms are not visible to the naked eye.

Back to top

Petri dish

Dish-shaped containers (about 9 cm or 3.54 in) named after the inventor Julius Richard Petri (1852–1921). They are transparent, usually made of disposable plastic, with a lid to prevent contamination. Agar-based media are poured into the dishes and allowed to cool, at which point, they turn into a jelly.

Back to top

Further Reading

Hitchens, Arthur Parker, and Leikind, Morris C. 1939. “The Introduction of Agar-agar into Bacteriology.” Journal of Bacteriology 37 (5): 485-93.

Hesse, Wolfgang. 1992. “Walther and Angelina Hesse – Early Contributions to Bacteriology.” ASM News 58 (8): 425-8 [Translated from German by Dieter H. M. Groeschel].

Corrado Nai. 2024. “Meet the Forgotten Woman Who Revolutionized Microbiology With a Simple Kitchen Staple.” Smithsonian Magazine (June 2024).

You might also like

EXHIBITIONS

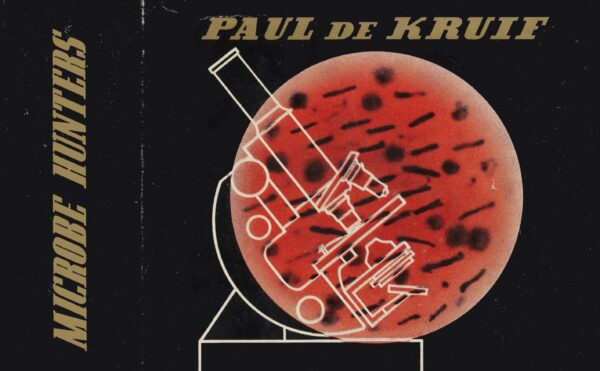

Sensational Science: A Century of Microbe Hunters

Our latest outdoor exhibition explores the nearly 100-year-old book that influenced generations of scientists.

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

Paul Ehrlich

This Nobel Prize-winning biochemist introduced the concept of a “magic bullet.”

THE DISAPPEARING SPOON PODCAST

Machiavellian Microbes

Parasites can force animals to do nefarious things by manipulating their minds—including, uncomfortably, the minds of human beings.