Elisabeth Bakker *

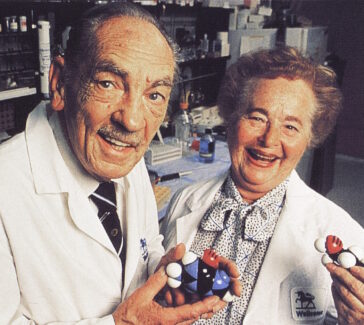

A biography of the fictional Elisabeth Bakker highlights the experiences of middle-class women in the history of early chemistry.

* This biography of the fictional Elisabeth Bakker has been created from the historical sources we have about the lives of women living in the Dutch Republic during the 17th century. It aims to provide readers with an understanding of the experiences and contributions of middle-class women to the history of early chemistry, despite the absence of archival materials commonly used to tell the story of an individual life.

Early modern women measured, sifted, boiled, and distilled, transforming raw materials into foods, medicines, cosmetics, and household products like ink, soap, and pesticides. While some women worked in alchemical laboratories, most worked in their homes. Their experiments were essential to 17th-century household economies; they foreshadowed later work in the modern scientific discipline of chemistry.

Youth

A woman sits in the foreground of An Alchemist and His Family painted by the Dutch artist Thomas Wyck (1616–1677). Let’s call her Elisabeth Bakker. Elisabeth was born in 1605 into a middle-class family living in Amsterdam. Both of Elisabeth’s parents were originally from Antwerp. After the Spanish Siege of Antwerp in 1585, they joined the mass of Protestant migrants who moved north into the newly formed Dutch Republic. As a child, Elisabeth saw Amsterdam undergo a rapid transformation, as the arrival of Protestant merchants turned what had been a modest fishing town into the commercial epicenter of the Republic.

As a merchant, Elisabeth’s father traveled for much of the year. While he was gone, her mother ran business and family affairs at home. Since literacy was central to running businesses, most women in mercantile families received an education. Around the age of seven, Elisabeth began to attend a Protestant school where she learned reading, writing, and arithmetic. At home, she received an education in Protestant morality, household economics, and cooking from her mother.

Young Adulthood

Elisabeth frequently accompanied her mother to the marketplace, where they would purchase ingredients and equipment to make household necessities. At the market, Elisabeth would have encountered butchers, vegetable sellers, and fishmongers, each of whom belonged to their own guild. While food markets occurred daily or weekly, other vendors selling specialty products only visited the city once per year. Products from far-away lands, such as the red wood of the brazilwood tree (imported by Portuguese merchants from Brazil), were likely offered at these annual markets. From her mother, Elisabeth learned how to assess the quality and cost of produce, and when to look for particular products based on the time of annual harvests or seasonal trading voyages.

Glassware or stoneware such as retorts, alembics, and receivers could be purchased year-round at home goods stores. Sometimes Elisabeth’s mother bought expensive copper pots and pans from second-hand shops. Quality kitchenware was a big investment for a family: a single pot might cost an entire month’s income. Apothecaries could mix medicines for customers, but they also sold a variety of plant, animal, and mineral ingredients for cooking and medicines. At the apothecary, Elisabeth would often see local artists purchasing plant and mineral pigments for their paints. Spices like saffron, ginger, and cumin could be purchased from the apothecary.

Left: Antique French stoneware retort, 1700s-1800s; Right: Replica of an antique top alembic.

As Elisabeth grew older, her mother also began to teach her some of the more technical skillsets of domestic alchemy. Early on, she learned how to make a special Dutch dish of poached eggs in saffron sauce. The saffron and bread were pounded together and mixed with milk. The mixture was then strained and boiled, at which point the eggs could be poached. Such recipes were available from new cookbooks that began to circulate in the Dutch Republic.

On occasion, Elisabeth’s mother would turn to the Koocboec oft Familiern Keukenboec (Cookbook or Family Kitchen Book), published in 1612 by Antonius Magirus. Often though, Elisabeth’s mother cooked from memory with occasional reference to the family’s recipe book, which she added to over the years.

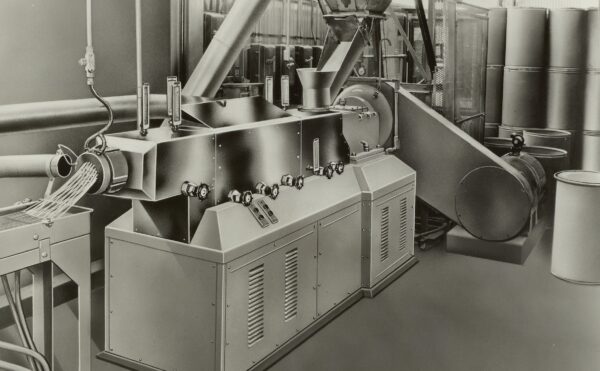

Much of the labor involved in the practice of professional alchemy overlapped with the techniques women used while cooking and producing household necessities. Elisabeth was familiar with making powders and pastes by grinding ingredients in mortars and pestles. Crushed rock alum, for example, was used to make a paste to clean the teeth. She also learned the skill of distillation, a chemical process by which a liquid is purified and separated into its constituent parts by boiling and collecting the condensation of its vapors.

LEARN MORE

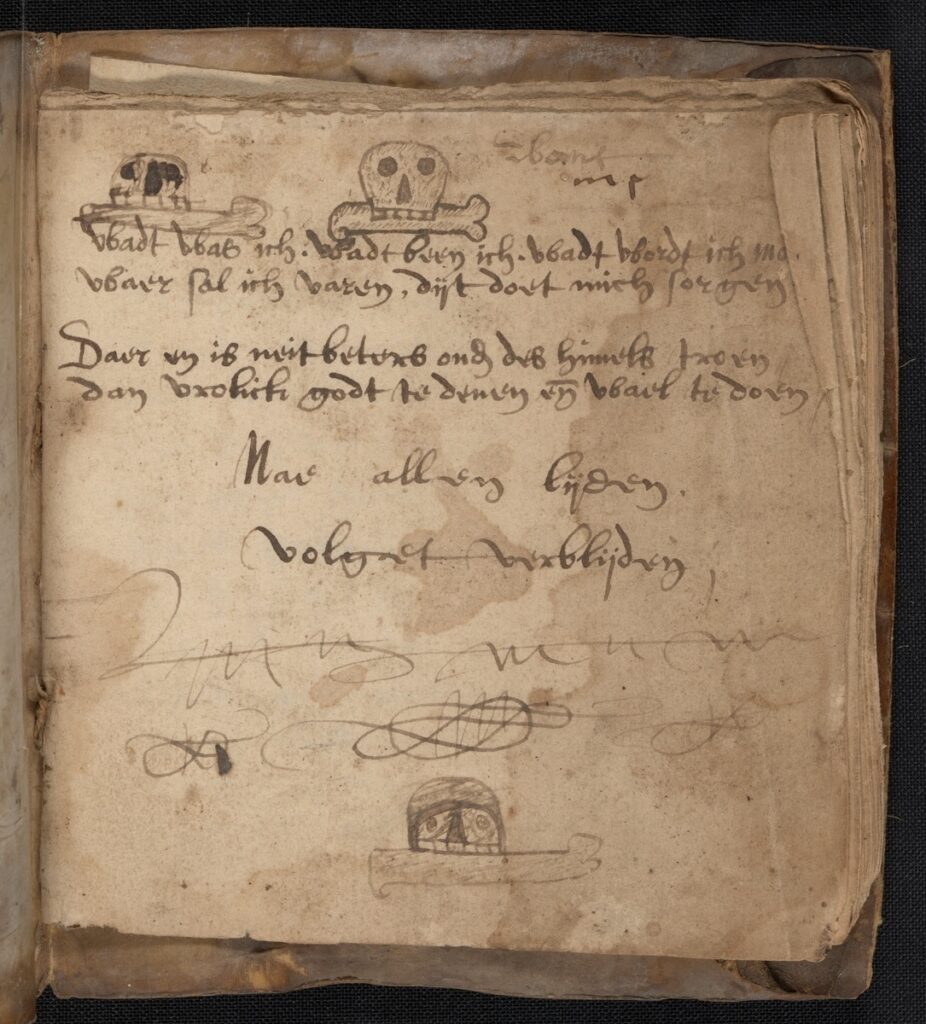

Though women were deeply engaged in chemical experiments before 1800, most of them remain anonymous. Historians often turn to the well-preserved records of universities and scientific societies to learn about science in the past, but women were excluded from these institutions. Their kitchen experiments were considered housewifery, not science. To understand their work, we have to look at recipe books and letters. These private records were meant to be kept in the family. As these materials were passed down through generations, sources and stories about their authors were often lost, making the biographical details of most middle-class household alchemists quite hard to find.

Pages from a 17th-century Dutch apothecary diary. This is a rare survival from Bakker’s day that historians can use to reconstruct early chemical recipes and the experiences of everyday people.

Alchemists like Elisabeth used distillation to make medicines, alcohol, scented herbal waters, and perfumes. Taking lavender leaves and rose petals, Elisabeth chopped and soaked them in water. Next, the floral water was placed into an alembic, which was heated over the fire. As the water boiled, droplets would condense on the interior dome of the alembic and slowly drip through the spout. A retort collected the concentrated liquid. This process produced an aromatic floral water, which could be used to cleanse the skin.

Married Life

In the 17th century, young women like Elisabeth Bakker had little say over who they married. Male relatives would introduce prospective suitors to women. If the match went well, the couple’s marriage would be arranged. Elisabeth’s father probably would have begun to search for a suitable husband for her when she reached her late teenage years. Let’s say he found one; a young man we’ll call Lucas Iansen. Lucas studied medicine at the University of Leiden and ran a private medical practice in Amsterdam. In 1624, Elisabeth married Lucas, with whom she would have two children, depicted in the painting.

Lucas had a deep interest in the medicinal value of precious metals such as silver and gold. He wanted to understand how precious materials could harness the power of nature to improve human health. These expensive medicines were commonly believed to cure all diseases and even to extend human life. At home, Lucas studied alchemy by reading books. Meanwhile, Elisabeth practiced alchemy in the kitchen while simultaneously overseeing her children, chopping carrots and onions for dinner, and monitoring a glass retort on the stovetop throughout the distillation process.

When her son got a cold, she would make him a distillation out of ginger and rue, a pungent and bitter herb with potentially dangerous pharmaceutical qualities. Bakker made hair dye for her husband’s beard out of burnt walnuts and made a dye from brazilwood to turn her shirts red. Relying upon kitchen tools, Elisabeth developed a first-hand understanding of the properties of natural ingredients, some of which were imported from around the world. She also developed a sophisticated technical skillset to make household necessities and take care of her family.

Further Reading

Berry Drago E. Painted Alchemists: Early Modern Artistry and Experiment in the Work of Thomas Wijck. Amsterdam University Press; 2019.

Hutton, Sarah. “Alchemy and Cultures of Knowledge among Early Modern Women.” Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal. Vol.15, No.2, (2021), 93 – 102.

Leong, Elaine. “Making Medicines in the Early Modern Household.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 82, no. 1 (2008): 145–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44448509.

Smith, Pamela H. The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution. 1st ed., The University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Van den Heuvel, D. “Partners in Marriage and Business? Guilds and the Family Economy in Urban Food Markets in the Dutch Republic.” Continuity and Change. 2008; 23(2):217-236. doi:10.1017/S0268416008006760.

Featured image: Detail of An Alchemist and His Family, oil on canvas by Thomas Wyck, 1600s.

You might also like

STORIES BY TOPIC

Women Do Science, Too

Although women have often faced barriers to participating in science—even sometimes seeing their contributions credited to men—science is definitely women’s work.

COLLECTIONS BLOG

A Crushing Task

On the hunt for the historical sources of an underappreciated field: mechanochemistry.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Women’s Business: 17th-Century Female Pharmacists

Although many were skilled in making medicinal home remedies, only a few women ran their own apothecaries.