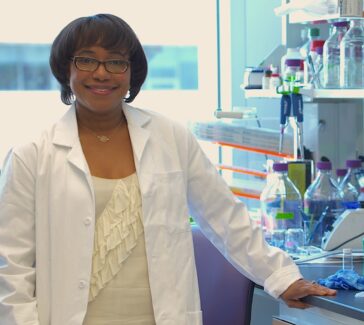

Eizi Matuda

The Japanese Mexican botanist made extensive collections of Central and South American plants, aroids and cacti in particular.

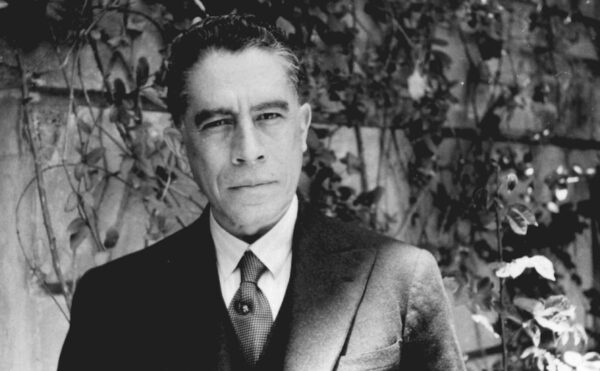

Eizi Matuda (1894–1978) was a botanist with a passion for Mexican plants. Once a professional swimmer, he was known for his ability to carry out physically demanding fieldwork. He took daring trips to rocky mountaintops to collect rare specimens for his herbarium and other botanical collections around the world. He was among one of the first groups of Japanese immigrants to arrive in Mexico as part of an agreement between the two countries to modernize through cultural and economic exchange.

Setting Sail

Matuda was born in Nagasaki, Japan, on April 20, 1894. He completed his high school education locally before moving to Formosa (Taiwan), then under the control of the Japanese government. Matuda began his undergraduate studies in botany at the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1911, and received his master’s degree in biological sciences in 1916. After graduation, he became an investigator with the Botany Department of the National Institute of Natural Sciences, carrying out studies in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Indonesia between 1917 and 1921.

In 1922 Matuda and his wife, Midohu Kaneko, made a daring decision to travel all the way around the world so that he could extend his botanical research to plants of the Americas. After many weeks at sea, they arrived in Chiapas, Mexico, a state in the south of the country with dense jungle vegetation. Here they settled at the Fujino Farm, a Japanese agricultural colony dedicated to the cultivation of coffee. With this move, Matuda and his wife became some of the first Nikkei—members of the Japanese diaspora—to make a life in Mexico.

Their migration was part of a much bigger political picture. The turn of the 20th century witnessed dramatic changes in both Mexico and Japan. On the one hand, Mexico sought to attract immigrants and foreign investment to promote business and modernization during a period of authoritarian rule known as the Porfiriato (1876–1910). On the other, Japan was adapting to a new political and economic system. The Meiji era (1868–1912) was characterized by an openness to new scientific, technological, political, and legal ideas. Following a period of extreme isolation, Japanese leaders wanted to expand the national economy through military and civilian programs abroad. Japanese settlement in Latin America was facilitated by the 1888 Treaty of Friendship and Commerce.

LEARN MORE

The first wave of Nikkei in Mexico travelled to Escuintla, Chiapas, where the Japanese government purchased land. Viscount Takeaki Enomoto promised an earthly paradise there that would support prosperous coffee farms. But when the colonists arrived, they found harsh, rocky conditions and were met with disease. Out of an original group of 33 settlers, only 6 remained in the Enomoto colony after a year. They emphasized the need for local collaboration to later waves of settlers from Japan. This emigration and other milestones are given in this historical sketch of relations between Japan and Mexico.

Eizi Matuda and Midohu Kaneko benefitted from difficult lessons learned by the first Japanese colonists in Latin America, who had settled the Enomoto Colony in 1897. Not prepared physically or culturally for the transition to Chiapas, nearly all of the Enomoto colonists had returned to Japan after a few short months. Matuda and his generation, by contrast, worked hard to involve themselves in the local community: they exchanged tools and agricultural techniques with local communities, collaboratively established programs for free elementary and high school education, and encouraged the Catholic faith. Matuda applied his botanical knowledge to the cultivation of coffee in these early years.

Research in Mexico

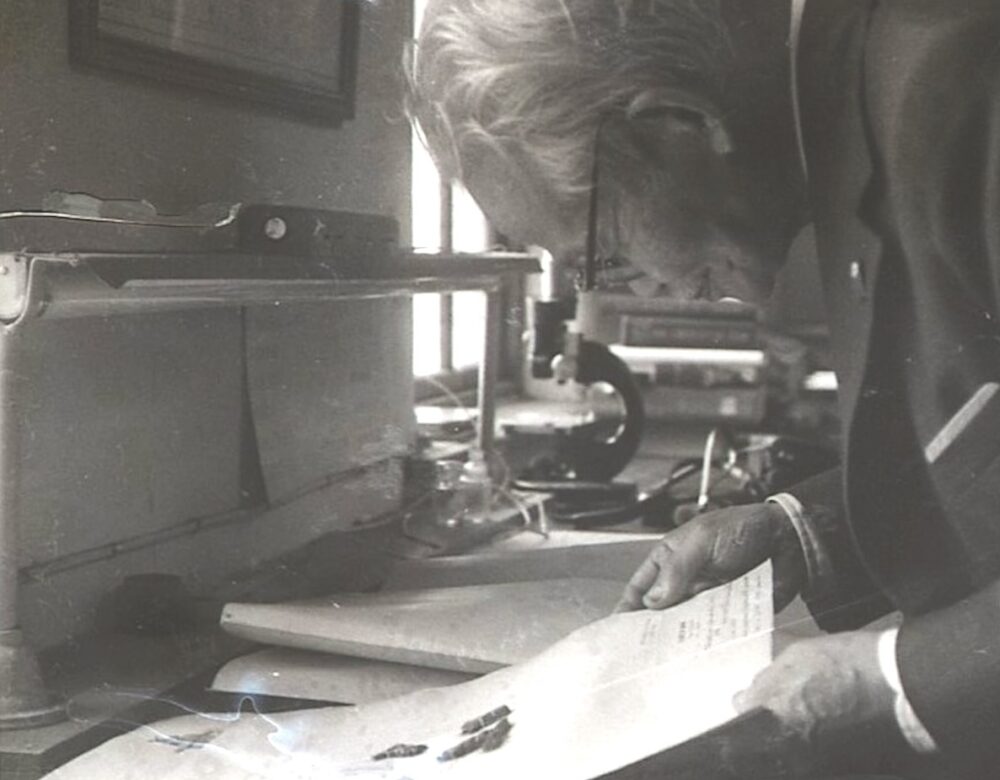

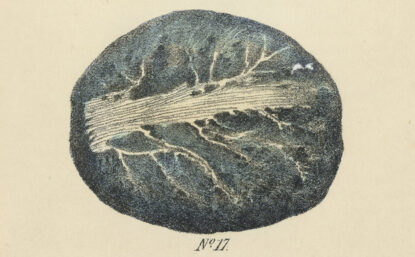

In 1932 Matuda established his own Botanical Institute in Escuintla, Chiapas. Most of his research focused on the classification of plants of the family Araceae—plants characterized by flowers that have two large leaves, or bracts, surrounding a fleshy stem.

But he also took a regional approach to botanical studies, collecting extensively in Chiapas and the State of Mexico, as well as internationally in Belize and Peru. He was especially interested in the plants of Chiapas as these formed a bridge between Mexican plants and those of Central America.

Matuda established a support network made up of both local researchers and botanists from around the world. He regularly discussed his findings with Harold Norman Moldenke of the New York Botanical Garden, who also helped him identify specimens according to their Latin names. He also entrusted samples to be identified by U.S. botanists Cyrus L. Lundell and P. C. Standley, leaving him time for extensive field research.

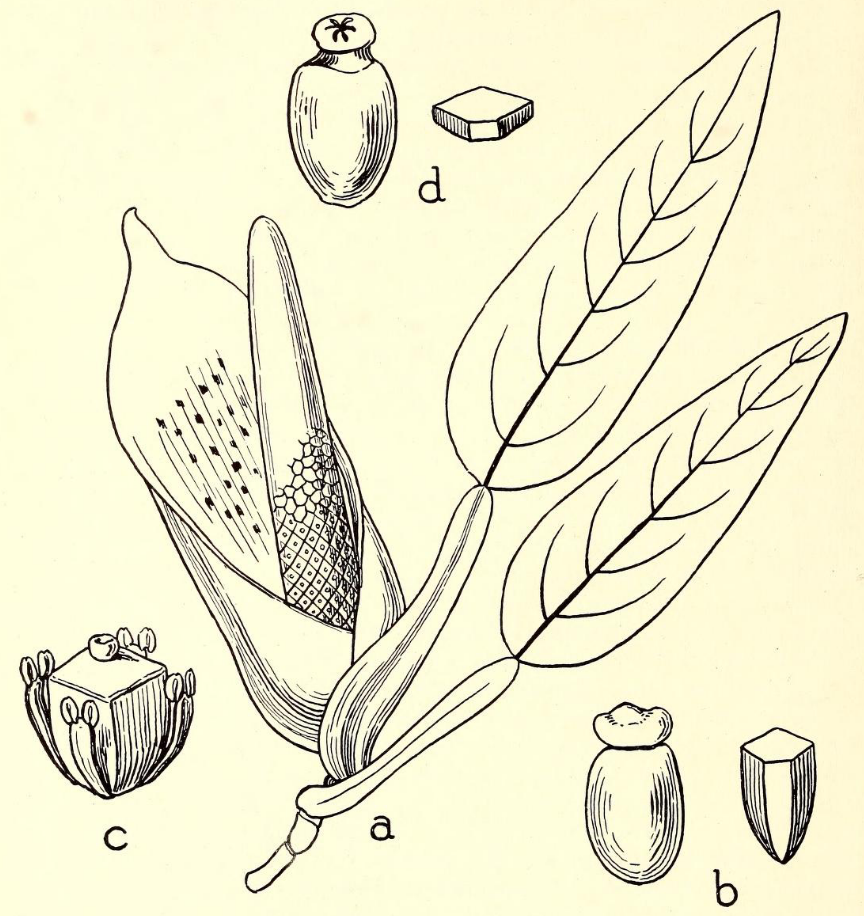

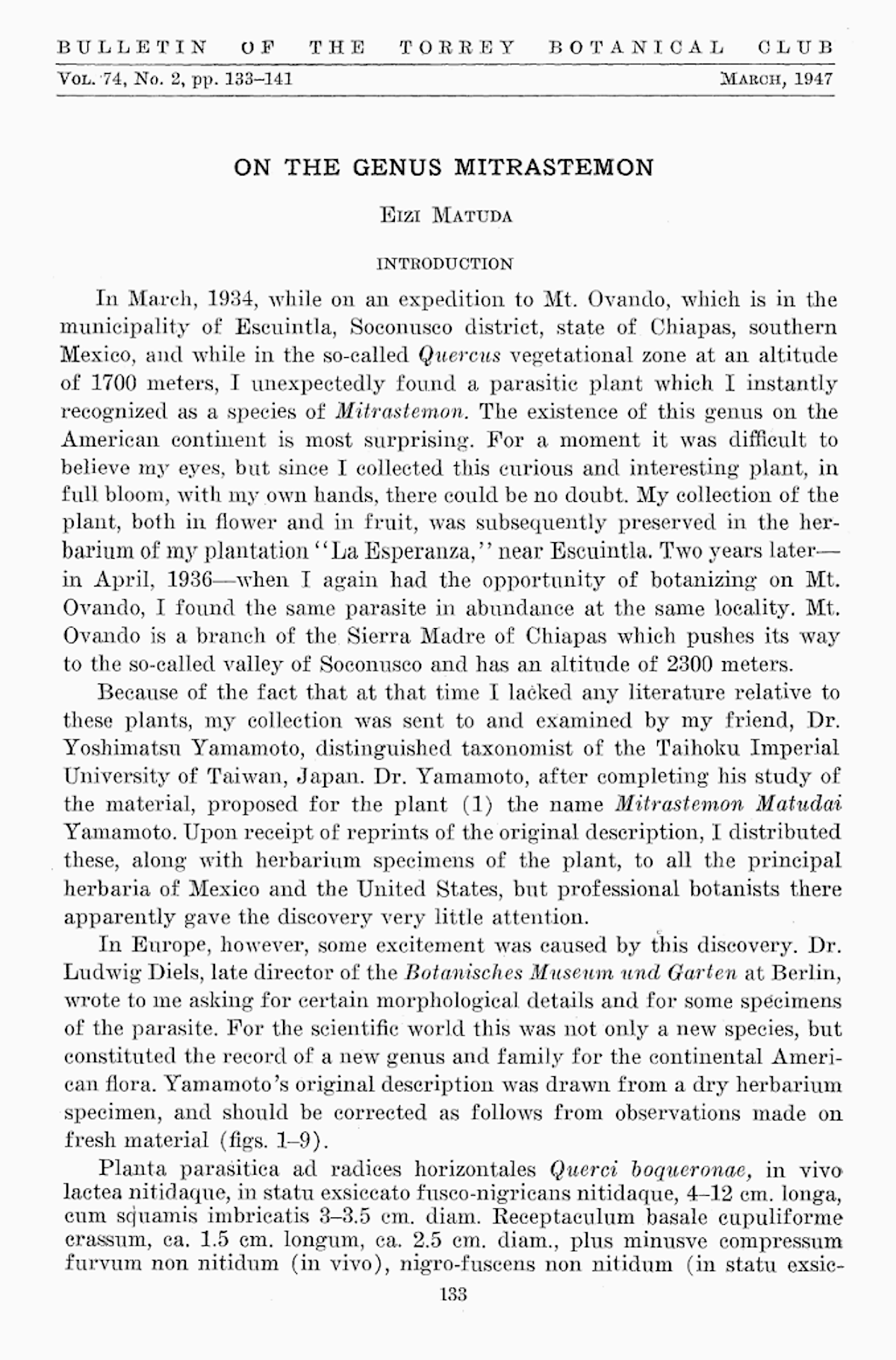

Much of Chiapas remained unexplored territory in the mid-1930s, and it was full of surprises. At Mt. Ovando, for example, Matuda found a group of Mitrastemon, a genus of parasitic plants. “[I]t was difficult to believe my eyes,” he later said of this discovery. Previously, Mitrastema had only been found in subtropical Asia—in Japan, for example. He was moved to find this trace of home in the mountains of Mexico, and he sent a specimen to colleague Yoshimatsu Yamamoto, who confirmed the plant’s identification.

LEARN MORE

In his paper, “On the Genus Mitrastemon,” Matuda reported the discovery of Mitrastemon on Mt. Ovando. What words does he use to establish himself as the plant’s discoverer? What evidence does he provide of the international scope of botanical research? What does he say about “dry” versus “fresh” specimens? What details do you see here about his personal life?

Indeed, many of the specimens Matuda collected ended up in research centers around the world, from the Field Museum in Chicago to the Botanical Garden and Museum in Berlin. In this way, Matuda’s research connected many of the most celebrated botanical research centers in the world.

As Matuda’s scientific reputation grew, he was offered a research professorship with the Biology Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). In 1950 he moved to Mexico City, where he joined the university and took up a position with the Institute of Forestry Research of the Secretariat of Agriculture and Livestock.

That same year, he met with other specialists in the study of Mexican flora: Helia Bravo Hollis, Hernando Sánchez Mejorada, Carlos Chávez, Juan Balme, and Dudley B. Gold. Together, they cofounded the Mexican Society of Cactology. This collaboration inspired Matuda to undertake a comprehensive survey of Mexican aroids (a family including monstera, arrowhead vine, and the taro plant). During the 1950s, he also conducted research with the Botanical Exploratory Commission of the government of the State of Mexico to identify and classify the flora of the state.

Roots and Branches

In 1962 the University of Tokyo awarded Matuda an honorary doctorate for his research on the botany and ecology of southeastern Chiapas. It is estimated that over the course of his career he collected more than 250,000 plant samples, 180 of which were new species. He described 2 new plant genera and published over 145 scientific papers. In 1983 the University of Sciences and Arts of Chiapas founded the Eizi Matuda Herbarium to complement its new biology degree program. He was also recognized with membership in the Botanical Society of Mexico.

Dr. Eizi Matuda died at the age of 84 on a field trip in Lima, Peru. A transplant, he made his home in Mexico and dedicated his life to the study of its plants. His research branched out from there to collections in the United States, Germany, Austria, Taiwan, and Japan, making the study of Central and South American flora part of a truly global science.

Glossary of Terms

Herbarium

A collection of plant specimens, usually dried or pressed, that have been preserved and described for scientific study.

Back >>

Porfiriato

The period of Porfirio Diaz’s presidency, 1876-1910, characterized by dictatorial repression and sweeping modernization.

Back >>

Meiji Restoration

A Japanese political revolution that ended the Edo Period in 1868, returning the country to imperial rule. It was followed by a period of rapid modernization and social change.

Back >>

Further Reading

Butanda, Armando. Contribuciones de Eizi Matuda (1894-1978) al conocimiento de la flora de México. UNAM, México, 1989.

Conabio. “Eizi Matuda (1894-1978).” Curiosos y Comprometidos, Biodiversidad Mexicana, https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/biodiversidad/curiosos/eizi-matuda.

Croat, Thomas. “Dr. Eizi Matuda, Mexican Aroid Specialist, 1894-1978.” Aroideana 1 (1978): 27.

Garcia, Jerry. Looking Like the Enemy: Japanese Mexicans, the Mexican State, and US Hegemony, 1897-1945. University of Arizona Press, 2018.

Matuda, Eizi. “A Contribution to Our Knowledge of the Wild and Cultivated Flora of Chiapas—1. Districts Soconusco and Mariscal.” The American Midland Naturalist 44 (1950): 513-616.

Featured image: Eizi Matuda visits the National Taiwan University Herbarium, 1971. Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

You might also like

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Forests of the Future

Modern agricultural practices are unsustainable. Is tree farming the answer?

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

Isaac Ochoterena

Jacobo Isaac Ochoterena y Mendieta was a self-taught scientist who created new programs for biology education and research in 20th-century Mexico.

DIGITAL EXHIBITIONS

Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Poisonous Plants

Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories from 1887 to 1927 open a window to the history of medicine and empire.