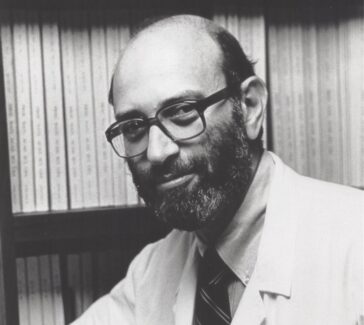

Charles Richard Drew

A pioneer in blood banking, Drew did extensive original research in blood chemistry.

This barrier-breaking African American doctor and surgeon earned the title “father of the blood bank” for his lifesaving innovations in the use and preservation of blood plasma.

A native of Washington, D.C., Charles Richard Drew (1904–1950) was a gifted young athlete who earned a bachelor’s degree at Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he was 1 of only 13 African Americans in a student population of 600. From Amherst he enrolled at McGill University in Montreal, receiving his medical and surgical degrees in 1933.

While doing his residency at Montreal Hospital (1933–1935), Drew became interested in the science and medicine of blood transfusions. In 1935 he joined the faculty of the Howard University College of Medicine and then the surgical staff at Freedmen’s Hospital, which was affiliated with Howard. In 1938 he was recommended for a Rockefeller fellowship to undertake specialty surgical training at Presbyterian Hospital in New York and pursue his doctorate in medical science at Columbia University. There he engaged in a project to create an experimental blood bank under a physician named John Scudder.

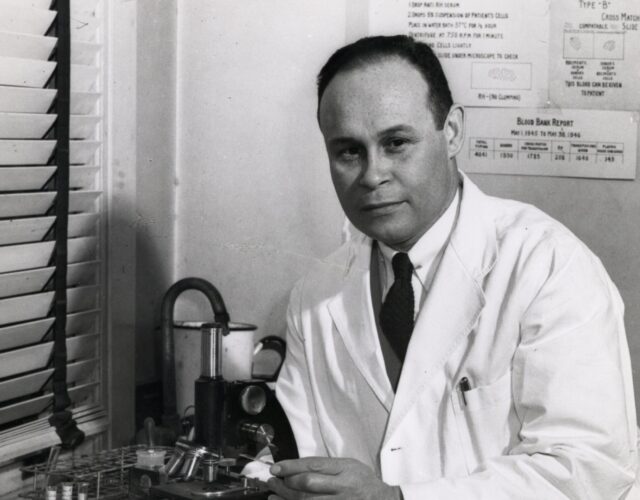

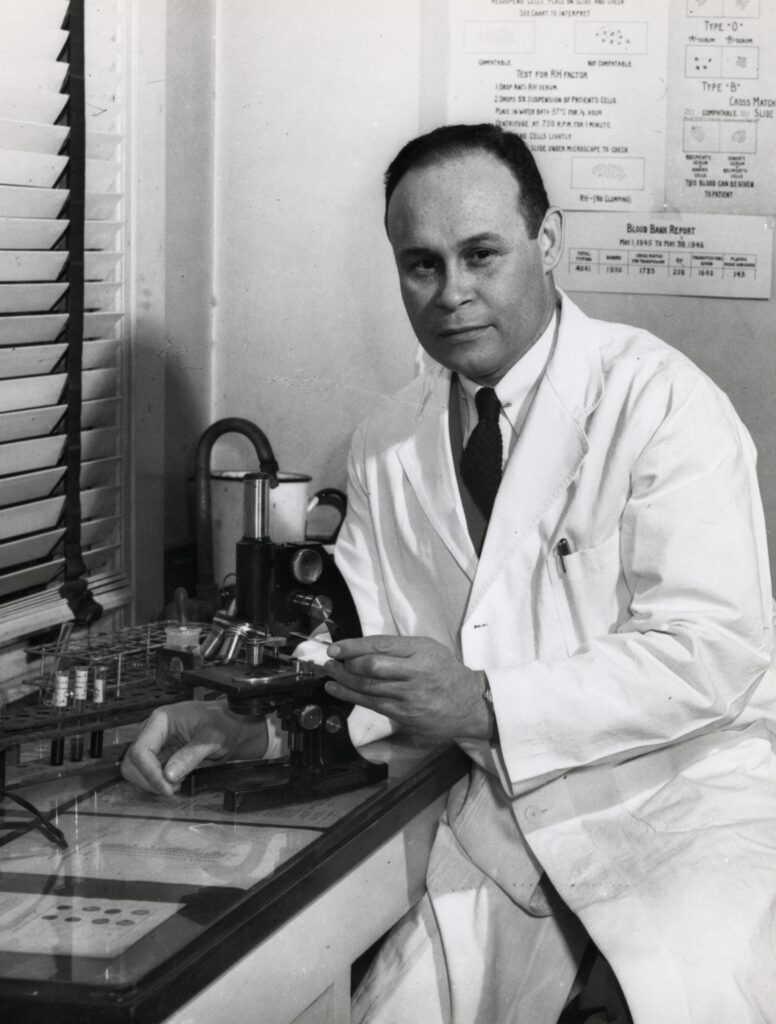

With Scudder, Drew did extensive original research in blood chemistry, fluid replacement, and the variables affecting blood preservation, culminating in a trial blood bank that ran for seven months and was a great success. With his 1940 doctoral thesis, “Banked Blood: A Study in Blood Preservation,” Drew became the first African American to earn a doctorate in medical science from Columbia.

Blood for Britain

World War II was already under way in Europe, and Great Britain desperately needed large quantities of blood and plasma to treat its wounded. A U.S. relief program—Blood for Britain—was initiated to collect and ship plasma overseas. Drew worked with Scudder to draw up the blueprint for Blood for Britain, using the Presbyterian Hospital experimental blood bank as a model.

The focus on plasma for the Blood for Britain program was rooted in plasma’s many advantages over whole blood. Blood has two main ingredients—red blood cells, which carry vital oxygen throughout the body, and plasma, which is mostly water with proteins and electrolytes. It turns out that plasma, though lacking in red cells, is often sufficient for replacing essential fluids and treating shock—thus saving lives until further treatment becomes available.

And because it spoils less quickly than whole blood, withstands transport better, is less likely to transmit disease, and can be used with any blood type, plasma is ideal for emergency situations such as the battlefield.

Drew and his colleagues set to work developing procedures for extracting plasma (using centrifuging and sedimentation techniques), preserving it against contamination, and packaging it on a grand scale. By the time Blood for Britain concluded in January 1941, more than 14,000 blood donations were collected and 5,000 liters of plasma shipped to England under Drew’s leadership.

Blood Banking on a National Scale

Blood for Britain became the model for a pilot national blood-banking program led by Drew and others for the American Red Cross. Among his innovations for this program were the mass production of dried plasma and the introduction of bloodmobiles—mobile blood-collection units that form the basis of “blood drives” as we know them today.

After the three-month pilot program, which served as the template for the National Blood Donor Service to collect blood for the U.S. military, Drew returned to Howard University in April 1941 to pursue his long-term goal of establishing a top-level surgical program for African Americans.

Having passed his American Board of Surgery exams, he was soon appointed chair of the Howard surgery department and chief of surgery at Freedman’s Hospital. In 1948 his first group of surgery residents passed their board exams.

Champion for African American Advancement and Rights

Drew tragically died in a car accident in 1950 at the age of 46. He is remembered for being outspoken against racial discrimination and segregation. Ironically, both the Blood for Britain project and the American Red Cross pilot program—to which Drew contributed so vitally—required that the blood donations of blacks be segregated from donations made by whites (the Red Cross pilot program initially did not accept black donors at all), and Drew openly criticized these policies.

He also petitioned many professional medical associations, including the American Medical Association, to allow African Americans among their ranks. In 1944 Drew was awarded the Spingarn Medal, the highest honor of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.