Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

By building connections between disciplines, the British-born astronomer transformed 20th-century understanding of stellar chemistry.

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin (1900–1979) identified the chemical makeup of stars in her 1925 doctoral thesis. By drawing together concepts from multiple scientific disciplines, she showed that stars were made primarily of hydrogen and helium. With this research, she became the first woman to earn a PhD in astronomy from Radcliffe College (present-day Harvard University).

LEARN MORE

Scientific writing usually refers to people by their surnames instead of their first names, but this can sometimes cause confusion. In many English-speaking countries, family names are patrilineal—children inherit their father’s names and women take their husband’s names when they marry. Such name changes can cause confusion when tracing women’s scientific work, especially if they collaborate with men. When she married Russian astrophysicist Sergei Illarionovich Gaposhckin in 1934, Cecilia Payne chose to hyphenate her name, rather than change it entirely. We refer to her here simply as “Payne” because our biography concentrates on the period before she was married.

“Dedicated to physical science, forever”

A friend once wrote of Cecilia Payne that, upon seeing a meteor at age five, she decided she “must begin quickly” in her pursuit of astronomy, “in case there should be no research remaining when she grew up.”

Payne entered Newnham College (a women’s college at the University of Cambridge) in the autumn of 1919 with plans to study natural sciences. The natural sciences curriculum at that time was presented in two sequential parts. Students selected three subjects of general interest in the first part before focusing in on a specialization in the second. Traditionally, a Newnham student would have studied botany, chemistry, and zoology. By “insisting on physics,” Payne carved out a path for herself that would better support her desire to pursue astronomy.

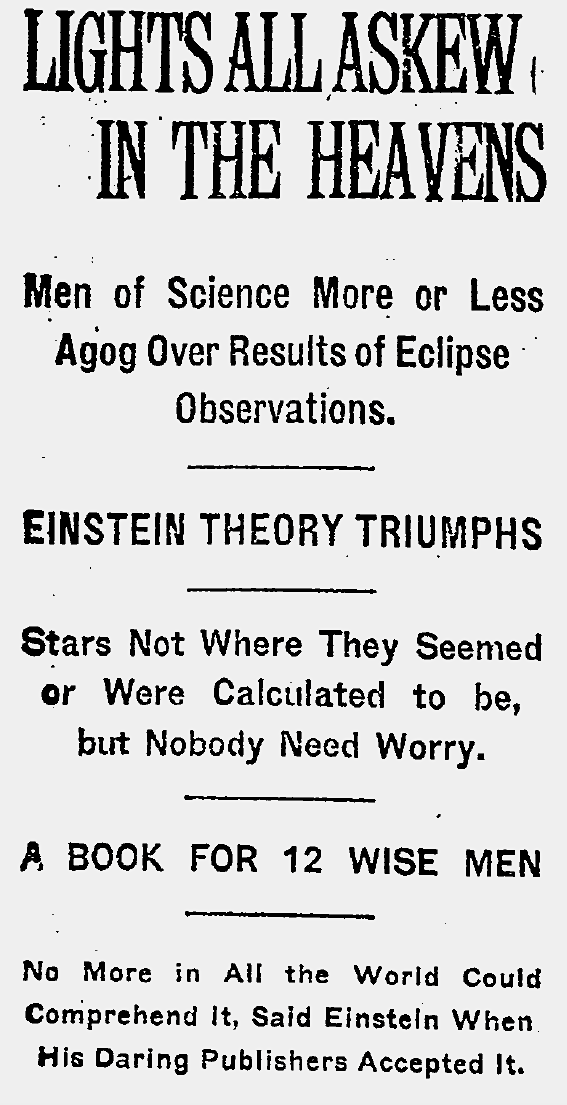

Payne’s love of physics grew when she heard Sir Arthur Eddington give a landmark lecture in December 1919. Eddington’s talk provided evidence supporting Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, using astronomical data gathered during a solar eclipse. The effect on her life was dramatic. As she recalled in her autobiography, she “was done with biology, dedicated to physical science, forever.” Payne sped through the rest of her curriculum, completing the typical three-year sequence in two years with a concentration on physics.

Payne noted that she entered college when the subject of physics was at “the parting of the ways.” With these words, she was referring to the split between classical mechanics, in which the behaviors of objects can be confidently predicted using Issac Newton’s laws, and quantum mechanics, which came to describe the unusual behaviors of atoms and subatomic particles with a new set of equations. This shift occurred because of key experiments around the turn of the 20th century, many of which were carried out by Payne’s mentors at Cambridge.

Payne studied quantum mechanics on the same campus that housed the famous Cavendish Laboratory. She attended courses taught by Ernest Rutherford and Niels Bohr, whose experiments and theories were integral to the new understanding of atomic structure, as well as H. J. H. Fenton, whose memorable lectures blended concepts across chemistry, physics, and astronomy.

Research at the Harvard College Observatory

Payne knew the traditional career for a woman trained in science would have been teaching. However, by the time she finished her coursework at Cambridge, she was more interested in research. She met with Harlow Shapley, director of the Harvard College Observatory, regarding a fellowship opportunity in astronomy, and she moved to America in 1923 to continue her scientific training.

The Harvard College Observatory was home to an immense amount of astronomical data, preserved photographically on over half a million glass plates. Many women scientists were employed there to help classify and interpret these data; the observatory was already home to several renowned astronomers, including Annie Jump Cannon (1863–1941), who had published her stellar classification schemes in the early 1900s.

LEARN MORE

The Harvard Plate Stacks provides a comprehensive list of women astronomers who worked at the Harvard College Observatory, timelines, reading suggestions, and links to get involved with the collaborative transcription of primary sources documenting this history.

When Payne arrived at Harvard in 1923, the dominant theory of stellar composition stated that stars consisted primarily of metallic elements, just like Earth. This implied that behavioral differences between Earth and the stars could be attributed to their vastly different temperatures. This view was held by such leading astrophysicists as Henry Norris Russell. From 1924 to 1925, Payne wrote her doctoral dissertation, turning her attention toward the stars to better understand their elemental makeup.

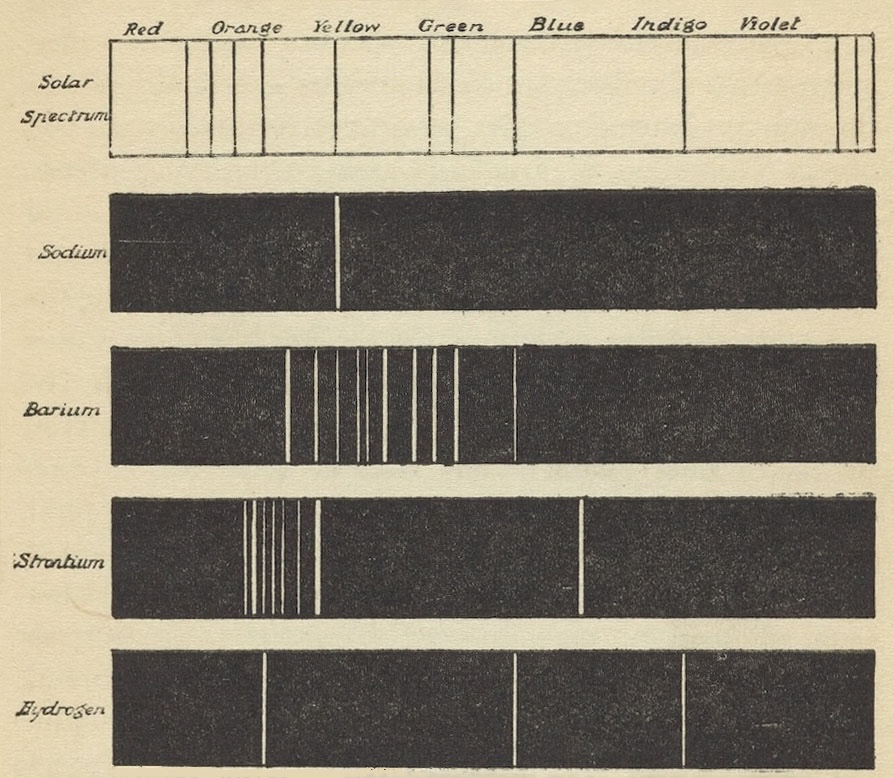

The breadth and timing of Payne’s scientific training served her well in the writing process. The observatory’s astronomical data took the form of line spectra (unique patterns of lines caused by starlight and preserved via photography). From her Cambridge coursework, Payne knew how to connect line spectra to the atomic behaviors predicted by quantum mechanics.

She could decipher each pattern as one might complete a fingerprint analysis, linking it to the element responsible. She also acknowledged her initial training at Newnham in terms of classifying complex information, later noting: “I still had a respect for descriptive botany: the study of systematics has left a mark on my approach to the stars.”

Complex scientific questions often defy disciplinary categories, and it is rare, given the nature of academic training, for one individual to bring such a broad range of knowledge to a project. Payne later wrote: “If my work has been of any value, that value has consisted in bringing together facts that were previously unrelated, and seeing a pattern in them. Such work calls for memory and imagination.”

Payne examined the abundance of elements in the stars: which elements, in what amounts, could be inferred from the stars’ observable line spectra? In contrast to the prevailing theory, Payne determined that stars consisted mainly of helium and (especially) hydrogen.

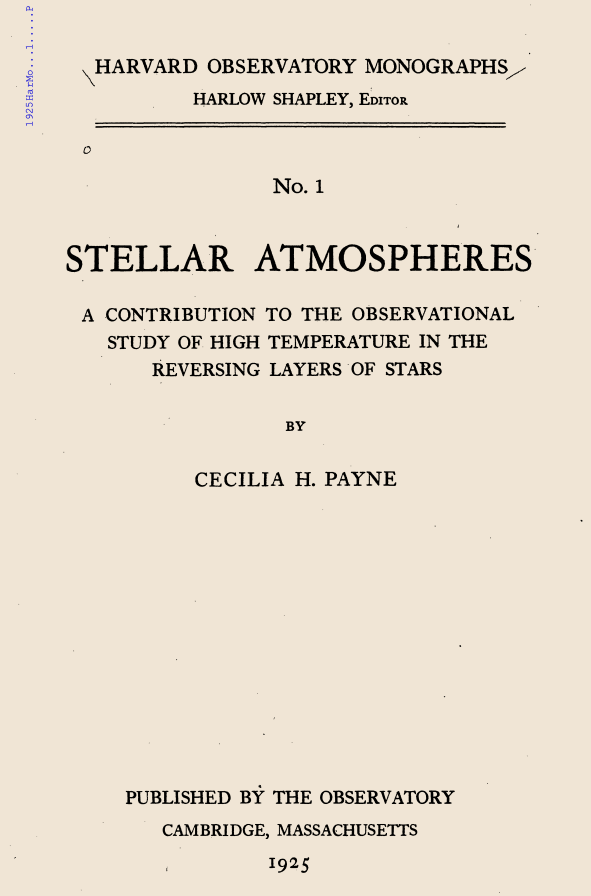

She wrote these findings up in her thesis, “Stellar Atmospheres: A Contribution to the Observational Study of High Temperature in the Reversing Layers of Stars.” She also noted that this composition was consistent across stars—their different colors were due to their different temperatures.

Russell himself was on Payne’s thesis committee. He contradicted her findings on hydrogen and helium during the writing process, and she ultimately included a qualification in her published thesis: “The enormous abundance derived for [hydrogen and helium] in the stellar atmosphere is almost certainly not real.” However, subsequent studies would corroborate Payne’s findings.

LEARN MORE

Read the first two paragraphs of Payne’s “Stellar Atmospheres.” What entities does she compare? What analogies does she draw?

A Stellar Academic Career

Payne remained at Harvard after earning her doctorate, serving in a variety of roles until her retirement in 1966. She continued research and served as editor of the Observatory’s many publications and was named a fellow of the American Association of the Advancement of Science in 1943. While she taught popular classes and wrote Introduction to Astronomy, a well-received textbook first published in 1954, she was not acknowledged as a faculty member for many years. Finally, in 1956, Payne became the first woman promoted to full professor at Harvard, as well as the first woman to chair an academic department.

Payne’s career allows us to see several historic transformations over a period of 50 years. As a student, she participated in the quantum revolution; as a junior scientist, she transformed understanding of the chemistry of stars; and in the last decade of her career, she broke new professional ground, climbing to the highest faculty ranks of a school that still, at the time, did not admit women students.

Further Reading

Haramundanis, K. Ed. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin: An Autobiography and Other Recollections; Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Bodanis, D. “The Fires of the Sun,” in E = mc2, a Biography of the World’s Most Famous Equation. New York: Penguin, 2000.

Moore, D. What Stars Are Made Of: The Life of Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2020.

Sobel, D. The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars. New York, NY: Viking, 2016.

Featured image: Undated photo of Ceclia Payne-Gaposchkin.

Courtesy of the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Harvard Radcliffe Institute

You might also like

STORIES BY TOPIC

Women Do Science, Too

Although women have often faced barriers to participating in science, science is definitely women’s work.

THE DISAPPEARING SPOON PODCAST

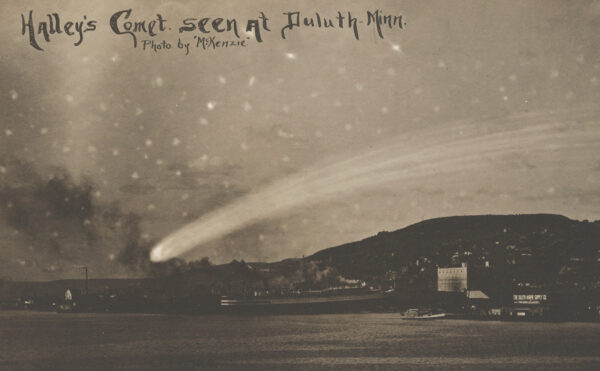

Comet Madness

Comets were long seen as portents of doom, but the spectrograph changed all of that. So why did everyone panic when Halley’s Comet returned in 1910?

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Making Space for Women in Astronomy

For centuries women have been looking at the stars despite earthly obstacles.