My eyes dart around the wood-paneled room and over to the circulation desk. Few sounds disturb the heavy quiet in here: an occasional cough; the scrape of a chair on the worn, creaky floorboards; the chirping wheels of the book delivery cart; the deliberately slow turning of a stiff, crinkled, centuries-old page. All my fellow readers are hunched over, absorbed in their own treasures. Good. Now’s my chance.

I lean in, my head inching imperceptibly toward my reading table and the 400-year-old encyclopedia of medicinal plants resting in its foam cradle. I check the room again, then move in closer. No one in the whole British Library is paying attention to me. No one suspects. A few more inches and I’m there, inside it. My eyes close. At last—I inhale.

Oh! That haunting smell. That musty, mossy, mushroom smell. The history it conjures! Castle and clock tower. River and hedgerow. Plague and pudding. Heartache and fog. Thrones, hay, and quinces. Rue, rosemary, ivy, and horn. Blackbirds baked in pies. Wet soil and maidenhair. The centuries of candlelight and English damp. Pages turned by blood- or berry-stained fingers. How many have held this book before me? Where has it been hidden? Whom has it saved? How has it . . . ?

And then it’s gone, my reverie shattered by the almost theatrically loud clearing of a throat. I turn and meet a librarian’s accusatory gaze. Yet in it there is a gleam of recognition: old-book smell.

Some people love it; some decidedly do not. Some people, like me, really love it, and I’m far from alone. “Old-book smell” is a thing. An internet search returns candles, incense, home fragrances, body lotions, and perfumes all claiming to re-create the intimate atmosphere of a cozy reading nook or the leather and mahogany elegance of a splendidly appointed study. There are even scents inspired by specific authors. (I received the tangerine, juniper, and clove of a Charles Dickens candle as a gift from my mother.)

Fanciful connotations aside, our sense of smell can trigger powerful emotions, memories, and reactions. Perhaps your attraction to the scent of old books began, like mine, as a parlor trick for your father’s amusement, guessing by smell the publication dates of vintage Mad magazines and Crypt of Horror comics. No? Then maybe it started on weekend visits to your neighborhood library. A whiff might conjure delectable hours whiled away browsing dusty, crowded aisles of secondhand bookstores or the comforting, familiar shelves in a loved one’s home.

Olfactory sensations can ignite intense responses and can influence mood, productivity, cognitive function, and physical actions. Smell is often used as a marketing tool to boost brand identity and to motivate consumers: retail stores, casinos, and hotels regularly employ high-powered misting machines and other diffusing systems to add ambient scents of coconut, citrus, or green tea to their spaces. Balsam, clove, and cranberry are popular artificial environmental fragrances used during the holiday shopping season. Realtors rely on the aromas of simmering spices or baking bread to inspire warm, welcoming feelings in potential home buyers. And, well, Cinnabon.

Old books have a potent, unmistakable smell, but it can be a hard odor to describe. That may be because no two books smell exactly the same. The complex scent is actually an amalgamation of specific chemical markers of decay that combine with how a book was made and how and where it was stored and used by the people who have touched it. In essence, when we breathe it in, we are simultaneously smelling the life—and the death—of a book.

The paper, inks, and adhesives that make up a book contain hundreds of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). As these components break down, VOCs are released into the air, and we detect them in the form of that distinctive odor. (New books release their own, very different VOCs. Inks, solvents, adhesives, bleaching agents, and other chemicals involved in modern manufacturing processes combine to produce the crisp, synthetic smell you notice when you snap open a freshly printed text, which, I suppose, can have its own appeal.) Environmental factors, such as the kind of climate or room a book was stored in—whether it was dusty or dirty or exposed to constant sunlight or mildew—all contribute to a book’s smell profile. Other variables are directly related to the habits of owners and how they used their books. Was someone snacking as they read? Did the reader spill wine, smoke a pipe, or sit fireside? Was the book used to prop a chair leg or kill an insect? Were flowers or locks of hair pressed between its pages?

Conservators, librarians, book dealers, and collectors have long used a book’s peculiar smells to glean information about its components and relative age and to diagnose its condition. The odor profile of a book can indicate its rate of decomposition and subsequent need of conservation. Although the sensory experience and description of smells are highly subjective, chemists have determined some VOCs are the result of the breakdown of certain materials that produce specific and easily recognizable odors. For instance, as the cellulose in paper decomposes, it emits furfural, which most people perceive as a sweet, almond-like fragrance. Lignin, present in the cell walls of trees (and therefore in all wood-based paper), emits benzaldehyde and vanillin, which impart a faint vanilla aroma. The decomposition of paper can produce such compounds as toluene, which can smell sweet or pungent. Hexanal, also from the disintegration of cellulose and lignin in paper, can give books an earthy, musty, “old room” smell, which could be exacerbated by mold from environmental exposure.

Smell, however, is not simply a matter of isolating and naming molecules. Odors, or at least the ways we perceive them, are affected by our age, cultural background, genetic makeup, gender, ethnicity, and even mood. Researchers at University College London’s Institute for Sustainable Heritage recently attempted to methodically unravel some of the mysteries of old-book smell. The goals of the study were to develop a vocabulary-based framework that connected the chemical composition of an odor to the way we sense and describe it. Employing techniques also used by perfumers, the university team captured VOCs emitted by a book published in 1928 they found in a used bookshop and collected air samples from the 18th-century library in St. Paul’s Cathedral. A gas chromatograph and a mass spectrometer were then used to analyze the captured molecules released from the samples. The result was a “historic book extract,” a kind of chemical profile of old-book smell.

The researchers gave volunteers a list of terms and asked them to sniff and then describe the odor character, intensity, and “perceived pleasantness” of the captured smell samples. From this data the researchers produced a Historic Paper Odour Wheel, which combined the sensory aspects of the odors and the likely chemical sources of those sensations. Much like the wheels used in describing aroma and flavor profiles of wine and coffee, the university’s wheel presents olfactory profiles in terms of human perceptions of smell and establishes a scent vocabulary specific to that odor.

The wheel breaks down the smell of old books into general aroma categories that include smoky/burnt, earthy/musty/moldy, sweet/spicy, medicinal, and grassy/woody. Another section of the wheel offers more expansive (and sometimes hilarious) sensory descriptors, such as mothballs, bourbon, fresh fruit, rotten socks, ash, body odor, caramel, and trash. The outer ring of the wheel indicates the likely chemical compounds that produce the smells. “Chocolate” and “coffee” were the descriptors most often used to characterize the old-book sample. Chemically, this perceived aroma can be explained by the fact that both chocolate and coffee start as beans, which contain lignin, cellulose, and high levels of furfural, vanillin, benzoic acid, and other compounds also found in decomposing paper. Considering the amount of wooden furnishings in the historic library, it’s not surprising that all the participants chose “woody” to describe the air samples taken from its interior.

Etching of a book scorpion (Chelifer cancroides), undated. The book scorpion is not a scorpion at all, though both are arachnids.

You don’t need special scientific instruments to identify some other kinds of book decay.

Bibliophiles of all ages proudly identify themselves as bookworms, voracious readers who devour books with insatiable appetites. It’s a perfectly fitting moniker since that’s what true bookworms do: they eat books.

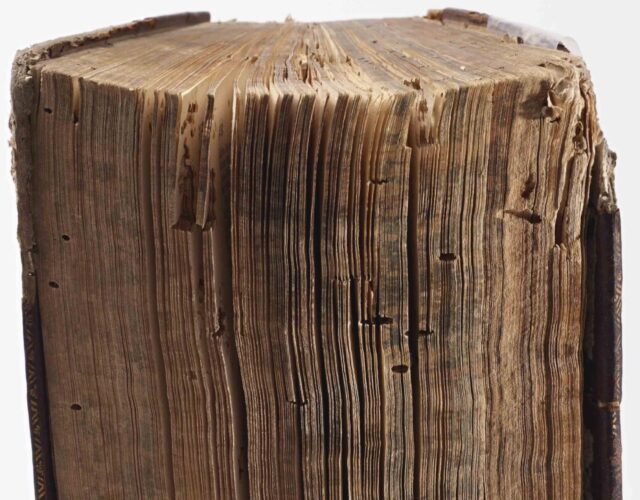

The term bookworm does not refer to a specific type of worm: in fact, these creatures aren’t worms at all. Rather, the name generically describes a variety of species of tiny beetle larvae and some species of moths. Adult female beetles lay their eggs on the edges and cracks of books and shelves, and the hatched larvae then burrow down through the paper seeking nourishment and protection. New adults eventually emerge, leaving pages chewed through with patterns and trails, holey covers, and shelves speckled with little piles of sawdust- or sand-like frass, or excreta.

During the first part of the 20th century, scientist and bookworm aficionado William R. Reinicke identified and studied approximately 160 different kinds of bookworms. Naturally, different species have different nutritional and environmental needs. Woodborers, such as the furniture beetle or woodworm (Anobium punctatum), the deathwatch beetle (Xestobium rufovillosum), and the Mexican book beetle (Catorama herbarium), eat paper, cardboard, and wooden shelving. Others, such as the drugstore beetle or biscuit beetle (Stegobium paniceum), survive on, among other things, the starches in natural fibers found in books and boxes. The carpet beetle (Anthrenus verbasci) feeds mainly on paper and animal products, including leather, horn, wool, hair, dried blood or food, glues, and the bodies of rodents and insects that have died in or among the books. Sometimes it’s the chemicals added or applied to paper—to aid in the absorption of ink, for instance—that prove most attractive to pests. Spider beetles, moth larvae, cockroaches, and other menaces are compelled to feast on adhesives and treatments that contain gelatin or other animal products.

The rooms and furniture that books are stored in and around can also endanger them. Species of wood-boring weevils attracted to damp shelves will chomp right through the books they house. Hot and humid environments, spaces with poor air circulation, or places prone to leaks, such as basements and attics, are all problematic. Damp paper also breeds microscopic mold, which serves as food for silverfish and book lice. Termites will bore through and feed on wooden book boards and furnishings.

Not all bookworms pose the same kinds of danger. Beetles can produce neat, tiny round holes, frequently along the spines of books; but they are also capable of mazes of destruction that meander through the helpless pages. Silverfish graze across the surface of paper and cloth, which leads to a scraped appearance or irregular holes. Some pests burrow straight down; some appear to wander erratically, almost calligraphically. Some trails can seem to resemble lace; others call to mind a Rorschach test or land elevations on a map. Mice shred paper for nests, and their feces and urine pose the threat of disease. Besides the holes, the excretions and secretions of pests can stain pages, lure other pests, or leave a smell—and not the good kind.

Bookworms have been the scourge of libraries and book owners for millennia. Early scribes used parchment, a writing medium usually made from the untanned skins of goats and sheep. Vellum, a finer-quality version, is made from the skins of calves. Both, unsurprisingly, contain animal proteins bookworms can’t resist. Their appetites and habits were recorded as far back as ancient Greece. In History of Animals (350 BCE) Aristotle describes “the creature resembling a scorpion found within the pages of books.”

Bookworms were still annoying scholars 2,000 years later. Natural philosopher Robert Hooke devotes an engraving to the bookworms he studied under early microscopes in his Micrographia (1665). Three kinds of book dwellers are depicted, including a “book scorpion” (Chelifer cancroides), which may well have been the culprit cited by Aristotle so long before. The most recognizable, however, is the one Hooke “found much conversant among Books and Papers, and is suppos’d to be that which corrodes and eats holes through the leaves and covers.” Though Hooke identified this as a bookworm or moth, he is describing what we now know as the silverfish (Lepisma saccharina). In observing the volume and degree of destruction (and digestion) this animal was capable of, Hooke remarks, “When I consider what a heap of Saw-dust or chips this little creature (which is one of the teeth of Time) conveys into its intrals, I cannot chuse but remember and admire the excellent contrivance of Nature.”

The “teeth of Time” in this case favor natural starches and sugars in pastes used in bindings and paper treated with proteins, such as casein (commonly found in milk) and dextrin, a gummy substance used as a thickening agent in printing inks. These days, ammonia-based pastes and alum additives repel book-eating pests, so bookworms tend to be more of a problem for rare-book curators and collectors.

In the age of e-books and tablets the idiosyncrasies of a printed book, let alone a decaying one, are erased. For the purpose of transporting, sharing, and keeping an author’s words efficiently stored, these technological changes have been mostly good. There is, of course, a trade-off to innovation. Readers experience a certain intimacy and form a different relationship with a work when they turn the fragrant, worn, or chewed-up pages of old books, witnessing in tangible ways the damage exacted by time. We observe the yellowing of a low-quality paper, the brown spots of “foxing” caused by mold spores attracted to iron in paper, the fading by the sun. Our fingers follow the waves of a warped cover or probe the latticework left by worms. We hear the crack as we open the dried spine of an aged volume or the whisper of fingers pulled gently across a smooth, dog-eared page. And, of course, we breathe in the beloved, beguiling old-book smell.