It looked more like a decadent hotel than a scientific institute. The Soviet Union’s Bureau of Applied Botany was housed in a grand, three-story building just off the majestic St. Isaac’s Square in Leningrad (modern-day St. Petersburg). It had dozens of elegant windows and a cream-colored façade with arches and pillars. It screamed high tea and starched collars.

But that appearance was misleading. Starting in the 1920s the bureau established itself as the premier institution in the world for studying and protecting the global heritage of human food crops—essentially, it was the Fort Knox of agriculture.

The bureau’s mission to protect the world’s food supply sprang from its director, biologist Nikolai Vavilov. Born in Russia in 1887, Vavilov witnessed some terrible force—drought, insects, disease, brutal cold—lay waste to crops across the country every few years during his childhood. One famine alone killed 400,000 people.

A peasant village during the Russian famine of 1891–1892, from Clara Barton’s The Red Cross in Peace and War (1899).

As he got older, Vavilov became obsessed with stopping famines and determined that the best solution involved the new field of genetics. In short, he reasoned that modern domesticated crops were susceptible to natural disasters because they were frighteningly inbred and lacked the genetic diversity to withstand hardships. Wild crops, in contrast, were usually more diverse and therefore hardier. By crossing wild and domesticated species, then, Vavilov hoped to make food crops hardier, too. This goal made Vavilov an early champion of what scientists now call biodiversity.

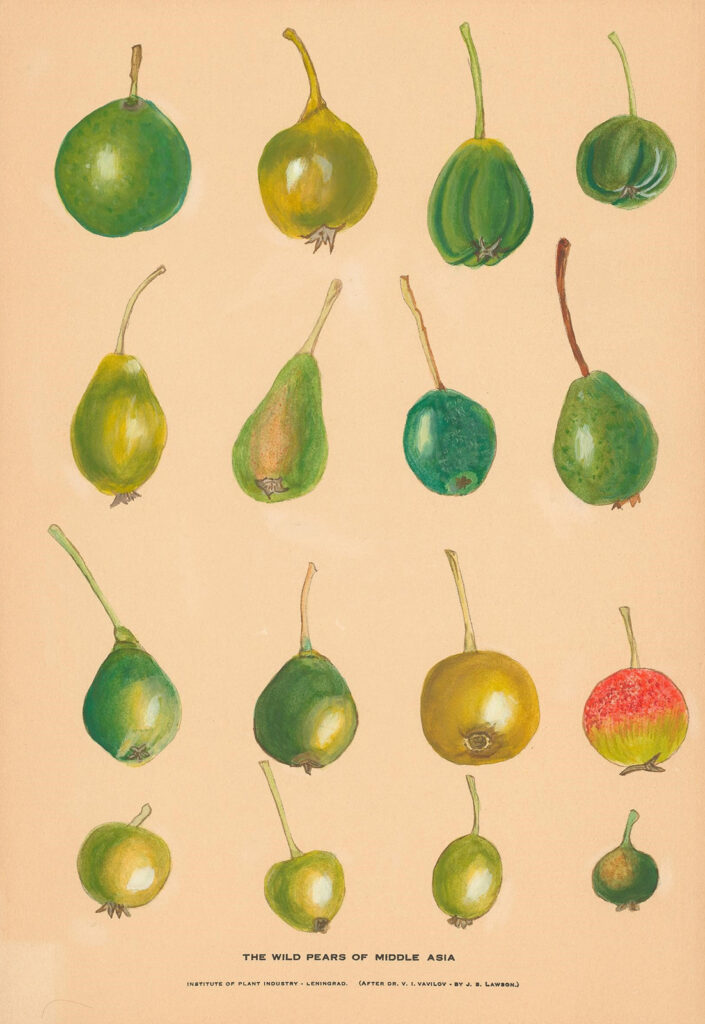

To achieve these crosses, Vavilov first had to gather the wild crops—and not just in the Soviet Union. Famines killed people across the globe. Unfortunately, even back in the early 1900s, human development was eradicating many rare varieties of wild food species. Vavilov leapt into action and in the 1920s began collecting and storing in Leningrad as many seeds, grains, fruits, nuts, and tubers as he could.

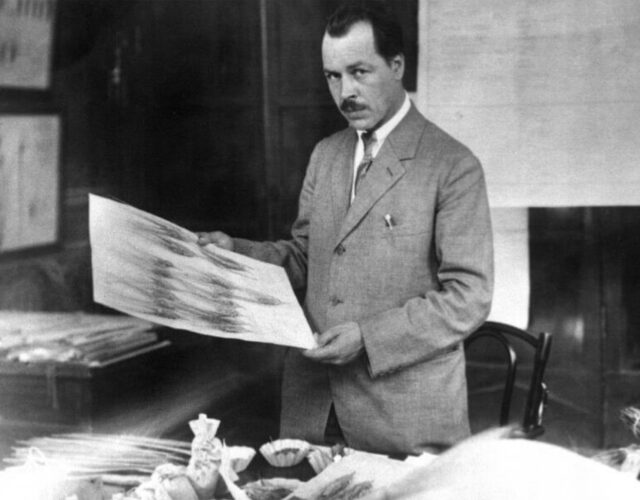

Clad in an Indiana Jones–style fedora and sporting a black mustache, he took collecting trips to five different continents. He eventually made 115 expeditions to 64 countries, collecting 380,000 samples. The variety he amassed was astounding. As one historian wrote of Vavilov’s collection, “some [seeds were] dull-coated while others glistened like jewels. . . . The tubers, roots, and bulbs came in all sorts of textures, from knobby and gnarled to as smooth and burnished as a clay pot.” Fruits collected “exuded nearly every fragrance imaginable to a perfume chemist—musky, fermented, citric, and floral.”

To replenish the seeds and tubers and whatnot, every so often Vavilov would send them out to fields, orchards, or paddies around the vast Soviet empire and have technicians grow them. The workers would harvest the resulting crops and send fresh samples back. The logistics were formidable, but by 1939 Vavilov had a humming empire of his own—25,000 workers under his command, all directed from the stately building in Leningrad.

But within a few years, that enterprise collapsed.

The problem was that Soviet apparatchiks despised genetics. To them the classic nature-versus-nurture debate in science—whether inborn genetic traits or outward environmental factors shape life more profoundly—was no debate at all. More specifically, the Soviets wanted to sweep away old human institutions and replace them with modern, supposedly “rational” ones. In doing so, they even hoped to build a new type of human—the New Soviet Man, a selfless, heroic worker. In other words, they hoped that by remaking the environment they could remake humankind.

Genetics, however, indirectly threatened this vision. Genetics emphasized fixed, inborn traits, implying that perhaps humans could not be refashioned so easily. Nowadays, most scientists view the nature-versus-nurture debate as too simplistic, but at the time, it was perhaps the debate in biology. And as good Marxists, top Soviet scientists declared that, because environmental factors were crucial to building the Soviet Man, genetics was therefore dangerous. Some Soviet officials went so far as to deny the existence of genes entirely.

One official was especially fanatic about stamping out genetics—Trofim Lysenko, a loathsome toady of Joseph Stalin. Lysenko first rose to fame as a young man when he published reports on new farming methods he had developed that produced unprecedently high yields of peas during harsh Soviet winters—reports he almost certainly faked. He was soon boasting of plans to grow lemon trees in Siberia, since of course inborn traits (e.g., sensitivity to certain temperatures) didn’t matter to plants as long as you “educated” them properly.

As Lysenko rose through the ranks, he also proved himself ruthless in stamping out opposition to his “science,” denouncing his rivals as spies and traitors. Eventually Lysenko used his influence to become the head of Soviet agriculture, at which point he pushed to outlaw genetics research and education in the Soviet Union. True to his autocratic nature, he declared that anyone who didn’t renounce the science would be arrested and thrown in jail.

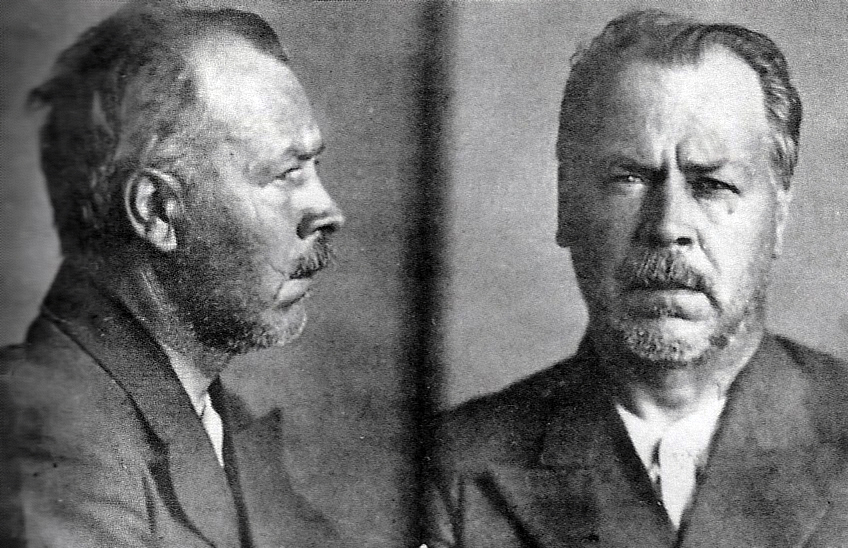

Vavilov, as a famous geneticist, was soon targeted. One day in 1940, while he was collecting seeds in Ukraine, Soviet security agents arrested him and whisked him off to the Gulag. Not even his wife and children knew exactly where he ended up. The arrest left his colleagues at the Bureau of Applied Botany trembling. They had every reason to fear they would be next.

Meanwhile, other threats to the bureau were looming in Europe. In June 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Leningrad was a major target of the Germans—in part because of Vavilov’s bureau. However despicable, Nazi scientists appreciated the power of genetics. (To a fault, in fact: they essentially committed the opposite error of Lysenko in arguing that nurturing and environment counted for nothing and genes alone determine our fate.) The Nazis knew that Vavilov had gathered a priceless trove of agricultural riches. They were eager to get their grubby hands on the bureau’s seeds and start experimenting.

Imagine what this knowledge must have done for morale at the bureau. Their boss had already been disappeared, and their own government had demonized them and called them traitors for their research. Now Nazis were marching on Leningrad, eager to steal their life’s work. Who wouldn’t despair?

Then things got worse. The battle for Leningrad deteriorated into a slog, and the Nazis laid siege to the city. Instead of shells and guns, their main weapon now would be the very thing Vavilov had worked his whole life to prevent—famine. They intended to starve the Russians into submission.

Soviet antiaircraft guns firing during the Siege of Leningrad, November 1941. The guns are positioned in close proximity to the Bureau of Applied Botany and St. Issac’s Cathedral, visible in the background.

During the first few months of the siege, people in the city pulled together. They ate tinned goods and stores of grains and tightened their belts to get by. Then supplies started dwindling. Rationing went into effect, then strict rationing, with adults limited to a quarter-pound of bread per day. Residents started hunting dogs and cats. Soon they were reduced to eating lipstick, leather hats, and fur coats.

The only food in the whole city, in fact, lay inside the bureau. Incredibly, though, the scientists there never dipped into their stores to ease their hunger pangs. They were starving while surrounded by food—they worked with food, thought about food, touched food every day. Yet none of them ever put a morsel to their lips. As one later said, “It was hard to walk. It was unbearably hard to get up in the morning, [even] to move your hands and feet . . . but it was not in the least difficult to refrain from eating up the collection.” This wasn’t just stirring rhetoric, either. One emaciated scientist actually died at his desk, holding a packet of nutritious peanuts in his hand.

How could they fight off such temptation? Why didn’t they say to hell with the Nazis, and to hell with Soviet officials who hated them, and eat the crops and save themselves? Probably because they weren’t thinking about themselves. They were thinking about bigger things.

Illustrations by J. S. Lawson of wild pears collected in central Asia by the Bureau of Applied Botany, one of a group of six panels Vavilov gave to Cornell University pomologist Richard Wellington at the International Genetics Congress in 1932.

First, they were thinking about the world after the war. Nations would need help getting back on their feet and feeding their people, especially in places where crops had been wiped out. They could help with that.

They were also looking at the broad sweep of human history. Ever since the first farmers planted seeds some 10,000 years ago, there’s been an unbroken chain of crop plantings through time. The bureau scientists saw themselves as stewards of this heritage—arguably the most important heritage of humankind. Eating the seeds would have been tantamount to snapping that chain.

So the scientists waited, and they watched, and they gradually died. A rice scientist, a potato scientist, the peanut scientist clutching that packet, and six more. In all, 700,000 people starved in Leningrad during the 872-day siege. But it’s hard to find any deaths more poignant than those nine food scientists.

The siege finally lifted in January 1944, when the battered Nazi army withdrew. The city was jubilant. Food, real food, flooded in, and people could eat their fill for the first time in years.

But it was a bittersweet moment for the surviving bureau scientists. They were happy to forget the gnawing hunger and constant temptation, certainly. But they were crushed at the loss of their colleagues. They were also disheartened to finally learn the fate of their guiding light, Nikolai Vavilov.

After the arrest in Ukraine, Gulag interrogators grilled Vavilov mercilessly, often for 12 hours at a stretch. They were determined to make him confess to the “crime” of not conforming his science to their politics. But as one historian commented, “Vavilov, unlike Galileo . . . refused to repudiate his beliefs.” Speaking for his colleagues, he looked his interrogators in the eye and said, “We shall go into the pyre—we shall burn. But we shall not retreat from our convictions.” Try as they might, the agents could not break him.

At least not mentally. Starting in spring 1942, Gulag administrators essentially did to Vavilov what the Nazis tried to do to Leningrad—starve him into submission. They fed him nothing but mashed cabbage and moldy flour day after day. The man who had sampled wild apples in Kazakhstan, wild barley in Ethiopia, and wild potatoes in Chile was reduced to eating flavorless mush, and little of it. His muscles wasted away, turning his arms and legs to sticks. His cheeks collapsed inward, boils erupted on his skin. He had labored for decades to end famine, and finally succumbed to starvation himself in January 1943. He was 55 years old.

Nowadays, Vavilov is revered as a hero in Russia—at least by most people. Despite its ups and downs, his bureau still exists, renamed as the N. I. Vavilov All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Plant Genetic Resources (VIR in Russian). Scientists across the globe have embraced Vavilov’s insight that genetic biodiversity is the key to a healthy food future. This has led to the founding of even bigger and more sophisticated agricultural stockpiles, such as the so-called doomsday seed vault in Svalbard, Norway. Fittingly, the VIR has donated seeds and other specimens to Svalbard—presumably many of them dating back to Vavilov’s early collecting trips.

Despite—or perhaps because of—Vavilov’s celebrity outside of Russia, his main tormentor, Trofim Lysenko, has enjoyed a shocking revival of his own within Russia. Instead of being denounced as a know-nothing murderer, he’s celebrated as a hero and patriot. This rehabilitation goes hand in hand with the country’s lurch toward autocratic, strongman politics reminiscent of Joseph Stalin’s day. The authors of a recent article on the Lysenko revival note that “the current enmity between Russia and the West [has] contributed to bolstering of pro-Lysenko arguments” in which geneticists “are depicted as pseudo-scientists and charlatans, performing tasks assigned to them by globalist agendas that are hostile to Russia. Opponents of Lysenko are called ‘traitors of the nation.’”

Russia’s increasing descent into autocracy also, of course, led to the recent invasion of Ukraine, disrupting food supplies there and sending the prices of Ukrainian wheat and Russian oil skyrocketing—all of which again raise the specter of famine.

Other threats exist as well. Despite advances in technology, crops today are more inbred than ever—and therefore even more vulnerable to pests and disease. Climate change could make things even worse as our weather grows more extreme: crops such as bananas, chocolate, and coffee are already threatened with extinction. Vavilov’s vision to preserve biodiversity is therefore more important than ever. Humankind has been farming for 10,000 years. And if we manage to last 10,000 more, we just might have Vavilov—and the incredible strength of the starving scientists of Leningrad—to thank for keeping us going.