The Paper Man

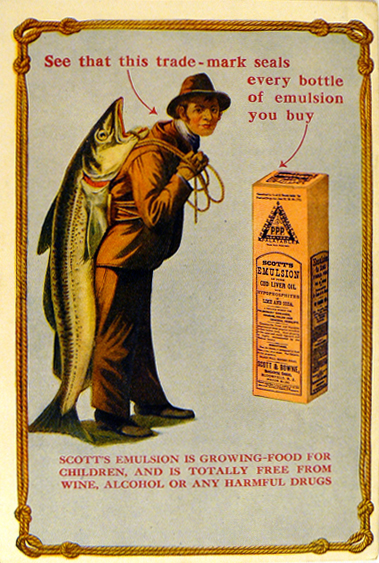

The man stoops forward, glances out from under the brim of his hat, legs braced under the weight of his load. A thick rope, wrapped around his waist, shoulders, and hands, secures the load on his back—a huge fish with gaping mouth and glassy yellow eye, its tail sweeping the ground. A common codfish, the Gadus morhua is recognizable by the brown and amber spots on its body, the light stripe down its side, and the three dorsal fins. The man has few identifying features, but the words “SCOTT’S EMULSION” appear along the hem of his jacket.

By 1900 “the man with the fish” was famous. His image was engraved and embossed on countless boxes and bottles of a cod-liver-oil preparation; printed in full color on advertising trade cards, booklets, and posters distributed around the globe; and in one instance painted several stories high on the side of a building in lower Manhattan. The man with the fish endures today, a testament to the persistence of an age-old tradition, even as scientific and commercial interest in cod-liver oil has waxed and waned.

A “Highly Disagreeable Remedy”

Northern European fishing communities used cod-liver oil for generations to restore health and alleviate aches and pains before the doctors and chemists of 19th-century Europe began to take an interest. Its manufacture was simple: cut out the fish livers (with gallbladders), throw them into barrels, and let them decompose. Fishermen often applied heat to extract the last bits of oil from the smelly, decaying mass. The oil grew darker during the rotting process, resulting in three grades: pale, light brown, and dark brown. “In those days,” wrote pharmacist F. Peckel Möller in his 1895 monograph Cod Liver Oil and Chemistry, “cod-liver oil was not a desirable article of consumption; indeed, to put the matter plainly, it was an abomination, and no one could have taken it willingly, even once, not to speak of day after day and month after month. Nevertheless many people did take it, and the only reasonable explanation is that the oil must have given strikingly favorable results.”

Edinburgh physician John Hughes Bennett played a part in introducing cod-liver oil to the English-speaking medical community. In 1841 he published his Treatise on the Oleum Jecoris Aselli, or Cod Liver Oil, after spending some years in Germany observing its use for the treatment of rickets (a disease marked by soft and deformed bones), rheumatism, gout, and scrofula (a form of tuberculosis). Bennett’s publication quickly spawned further research and experimentation by medical practitioners on both sides of the Atlantic, resulting in the growth of a large cod-liver-oil industry in New England by mid-century.

Northern European fishing communities used cod-liver oil for generations to restore health and alleviate aches and pains.

Ludovicus Josephus de Jongh of the Netherlands produced the first extensive chemical analysis of cod liver in 1843. His studies of the efficacy of the three grades of oil led him to conclude that the light-brown oil was the most therapeutic. He attributed this superiority to the larger quantities of trace substances found in it: iodine, phosphate of chalk, volatile acids, and “elements of bile.”

In 1846 de Jongh traveled to Norway to procure the purest oil available. By the 1850s “Dr. de Jongh’s Light Brown Cod Liver Oil” was marketed throughout Europe and exported to the United States. Each bottle bore de Jongh’s signature and stamped seal—a blue codfish on a red shield—guaranteeing that the product was “put to the test of chemical analysis.” Advertising emphasized de Jongh’s credentials as a physician and chemist and included testimonials from other men of science and medicine. As one 1869 advertisement stated, “It was fitting that the Author of the best analysis and investigations into the properties of this Oil should himself be the Purveyor of this important medicine.”

Even the most steadfast proponents of cod-liver oil, such as de Jongh and Bennett, admitted that the highly disagreeable taste and smell presented a significant hurdle to its use. In 1873 Alfred B. Scott came to New York City and, along with partner Samuel W. Bowne, began experimenting to produce a less nauseating preparation of cod-liver oil. Three years later they established the firm of Scott and Bowne, and began marketing their product as Scott’s Emulsion. Though not a doctor or pharmacist by training, Scott had the eye for opportunity that was necessary for achievement in business. Advertising, the two men believed, would propel their product to success. And so it did: by the 1890s Scott and Bowne had factories in Canada, England, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and France, and advertised their emulsion throughout the Americas, Europe, and Asia.

Scott procured his oil for Scott’s Emulsion directly from the Lofoten Islands, a long chain located above the Arctic Circle and the world center of cod fishery. As Möller whimsically described the islands in Cod Liver Oil and Chemistry:

While the tourists preferred to visit the Lofotens in the middle of summer, the codfish streamed to the islands in early January to spawn, and by the end of April were gone. The fishermen—around 30,000 of them in the 1890s—arrived in their boats and set up temporary residency in anticipation of the cod. The confluence of the Gulf Stream, the arctic waters, and the topography of the Norwegian fjords all conspired to create an unparalleled breeding ground for the codfish and, subsequently, an unequaled fishing industry. The midnight sun, the Maelstrom, the awe-inspiring coast, and the natural mysteries of the ocean and its creatures created an idyllic aura over what was in reality a harsh, exhausting, and smelly business.

“As Palatable as Milk”

De Jongh believed the problem of palatability could be surmounted with a little perseverance or “a little preserve for children, some fruit, a biscuit, or a drop of Bordeaux or Sherry wine.” Despite such assurances, much discussion and advice revolved around overcoming the nauseating taste and smell. Often the oil was mixed into coffee, milk, or brandy; some recommended taking the oil with smoked herring, tomato ketchup, or in the froth of malted beverages. Those with an “insurmountable aversion to the taste” could take the oil by enema.

Scott and Bowne carefully distinguished their tastier product from other “secret” remedies, openly publishing the formula in early advertising: “50 per cent. of Pure Cod Liver Oil, 6 grs. of the Hypophosphites of Lime, and 3 grs. of the Hypophosphites of Soda to a fluid ounce. Emulsified with mucilage and Glycerine.” The mucilage used was probably gum acacia. The glycerine added sweetness and was also thought to have tonic and healing properties. The hypophosphites of lime (calcium) and soda (sodium) were considered helpful in the treatment of consumption.

Scott and Bowne’s first trademark, registered in 1879, included the initials P.P.P. and three words—“Perfect, Permanent, Palatable.” The mark reflected their perfect formula; a permanent emulsion, that is, one that would not separate; and most important, a palatable one. One advertisement proclaimed, “You do not get the taste at all; because the little drops of oil are covered over in glycerine, just as pills are covered in sugar or gelatine.” “Palatable as milk” became a key tagline in Scott’s advertising.

The man with the fish on his back first appeared on Scott’s Emulsion around 1884 and became Scott and Bowne’s trademark in 1890. As Scott told it, he saw this fisherman with his record-breaking catch while on business in Norway. A photographer was quickly found to record the scene; later the photo was faithfully reproduced and registered as the company’s trademark. Trade cards and booklets featured the fisherman and his catch along with the words, “Scene taken from life on the coast of Norway” and “This Codfish, weighing 156 pounds, was caught off the coast of Norway.” The realistic image, a direct reference to the natural source of the medicine, served as a reassurance of quality in a marketplace of adulterated goods. Man and fish also evoked the romance and myth of the sea and the fisherman, who procures the bounty of the sea.

Scientific Medicine and “The Great Flesh Producer”

Cod-liver oil’s reputation as an effective treatment for “consumption,” a leading cause of death in the 19th century, led to its widespread popularity. A variety of diseases like scrofula, phthisis, tuberculosis, rickets, and rheumatism were understood to be manifestations of “consumption” or “wasting diseases.”

In 1882 Koch’s discovery of the tubercle bacillus, the “germ” that causes tuberculosis, launched a new era of scientific medicine. However, the new knowledge did not immediately yield effective new treatments, and the popularity of the old remedies remained unaffected. In their advertising Scott and Bowne recognized the role of microorganisms in disease, describing the cause of consumption as a growing germ that destroys the lungs much as a growing germ causes the “moulding of cheese.” As they explained, the germ itself is harmless until it finds some “smothered, starved, or tired, spot” within the body to grow. The strength of their product rested in its power to nourish the body and build up resistance to the germ. With Scott’s Emulsion, the thin and frail become plump and robust, and it was proudly proclaimed the “Great Flesh Producer.”

Pharmacological science in the 19th century focused on the identification and study of the “active principles” of the crude drugs. The isolation of plant alkaloids—such as morphine from opium and quinine from cinchona—provided medicine with substances of increased potency and known quantity that could be administered with more predictable results. Investigators sought the same success with cod-liver oil. In 1888 French chemists Armand Gautier and Luis Mourgues published an analysis of the active principles in light-brown cod-liver oil titled “Les alkaloides de l’huile de foie de morue.” Their findings echoed the earlier studies of de Jongh in their preference for the light-brown oils over the other varieties.

With the discovery of vitamins the medical world transformed cod-liver oil from a remedy largely dismissed as old-fashioned to an indispensable part of every child’s diet.

Although the medical community continued to debate the value of any “extract” of cod-liver oil, the commercial appeal and profitability of these products remained. Vinol, Wine of Cod Liver Oil, was one popular product, introduced in the late 1890s by Charles Kent and Company, Chemists, of New York City. In the company’s own words “Vinol is cod liver oil with out the oil.” The very fat that many still considered to be the essence of cod-liver oil’s therapeutic value had become the vile, useless, greasy part.

Scott and Bowne responded to the claims of the new popular extracts in their advertisements in the early 1900s:

As continued investigations failed to settle the controversy surrounding cod-liver oil’s “active principles,” the oil dropped out of favor with many doctors. The United States Dispensatory of 1918 summed up the situation thus: “Whether or not [the oil] acts simply as a foodstuff or whether it has some direct influence on the bodily metabolism, is open to dispute.”

The Oil and the Vitamin

Even as the 1918 Dispensatory edition was readied for publication, new research challenged its conclusions. In 1912 Polish-born biochemist Casimer Funk concluded that the lack of some essential nutrient caused certain diseases, such as beri-beri, pellagra, scurvy, and rickets. He coined the term vitamine (soon changed to vitamin) to describe these as yet unidentified substances.

Cod-liver oil played a central role in the nutritional research that uncovered the secrets of these mysterious vitamins. In experiments with rats at the University of Wisconsin in 1913, Elmer McCollum and Marguerite Davis proved the existence of an essential nutrient in cod-liver oil, dubbing it “fat-soluble A.” By 1922 McCollum identified another vitamin in cod-liver oil—the antiricketic “fat-soluble D.” Cod-liver oil was an important source of two “new” essential nutrients: vitamin A for growth and healthy eyes and vitamin D for the proper development of bones. Although recognized for a long time, rickets developed into a considerable health problem in the early 20th century, especially in the children of the urban poor.

Neither Scott nor Bowne lived to see the advent of the age of vitamins, which became the new “wonder drugs” and a boon to the marketers of cod-liver oil. The two died in 1908 and 1910, respectively, as wealthy men. Their emulsion survived them; advertisements in the 1920s touted the health-promoting properties of the vitamins—proof that modern science had vindicated an old remedy.

With the discovery of vitamins the medical world transformed cod-liver oil from a remedy largely dismissed as old-fashioned to an indispensable part of every child’s diet. Health professionals urged mothers to dose their children daily and provided much advice on how to get babies to swallow the nasty stuff. “Guile Baby into Regarding Cod Liver Oil as a Treat” headlined one newspaper health column, which continued, “It remains for the mother to sternly squelch any disposition to be ‘sniffy’ about cod liver oil. She must assume that bright, alert expression which is so natural to her when she offers the baby something simply marvelous.” Pamphlets on infant care issued by the U.S. Children’s Bureau demonstrated the proper method of administering the oil: a “forced feeding” that included squeezing the baby’s cheeks together to prevent it from spitting out the oil.

Synthetic replacements irreparably broke the age-old connection of the fish, the fisherman, the land of the midnight sun, and the “villainous fluid” they produced.

New research also gave renewed credence to the idea of active principles separable from the bulk of the nasty oil. In 1927 Casimir Funk and Harry Dubin, working for H. A. Metz Laboratories, patented a process for extracting vitamins A and D from the oil. Their patent application begins, “This invention relates to the treatment of cod liver, cod liver oil, or its derivatives for the purpose of obtaining therefrom a highly concentrated substance rich in the antixerophthalmic and antirachitic vitamines [A and D], to which, as has been definitely established, cod liver oil owes its therapeutic action.”

Oscodal Tablets, the resulting “vitamin pills” marketed by Metz, were sugar coated, making them all the more palatable. In the initial advertising campaign the Metz Company sent leaflets and literature to “all the physicians in the United States,” and salesmen personally visited thousands. Metz distributed free samples with the advice that doctors try it on “one of those ‘fussy’ patients who cannot take cod liver oil but still need it.”

The Scott and Bowne Company also introduced a “vitamin pill” concentrate of cod-liver oil in the early 1930s. The man with the fish on his back appeared on the packaging, a reminder that codfish were still the source of the product.

“Emancipation from the Fish?”

As scientists unraveled the role of vitamin D in cod-liver oil, others worked on a way to supply the vitamin without the cod’s liver. Scientists identified ergosterol, a substance extracted from the fungus ergot, as the molecular precursor to vitamin D. When irradiated, ergosterol became several hundred thousand times as potent as cod-liver oil. The compound, marketed in an oil base as Viosterol, was added in minute amounts to fortify other products with vitamin D. One columnist heralded irradiated ergosterol—first announced to the public in 1927—as ushering in “the final triumph of chemistry” and added that vitamin synthesis would mark our “emancipation from the fish that swim in the ocean and the vegetation that grows on the land.”

Emancipation took some time. Cod (and other fish) liver oil continued to be the preferred daily supplement, and Scott’s Emulsion remained on the market as a popular and more palatable alternative to pure oil. Advertising copy in the 1940s and 1950s emphasized Scott’s “natural A&D vitamins and energy-building natural oil factors.” However, the large-scale production of synthetic vitamins and vitamin fortification of other foods gradually undermined our dependence on traditional “natural” sources. Synthetic replacements irreparably broke the age-old connection of the fish, the fisherman, the land of the midnight sun, and the “villainous fluid” they produced.

But in the 1970s Danish doctor Jorn Dyerburg connected diets based on cold-water oily fish to a low incidence of coronary disease among the Greenland Inuit. His work led to further studies on the health benefits of omega-3 fatty acids and so paved the way for the innumerable fish-oil supplements seen on the market today. The new research, still ongoing, strongly suggests that there is more to the therapeutic value of cod-liver oil than its vitamins.

Scott’s Emulsion weathered the changes in medical knowledge, therapeutic practice, and cultural preference. Still produced today in much the same formula, the emulsion remains rich in vitamins A and D, calcium, phosphorus, and nowomega-3 fatty acids. Its therapeutic claims echo a long tradition of use: promoting healthy growth, building resistance to disease, and guarding against the ravages of age. Although the emulsion is no longer widely used in the United States where the vitamin pill mostly supplanted it, it remains popular in Asia and Central and South America, markets pioneered by Alfred Scott in the late 19th century. The man with the fish on his back still appears on every package, a testament to a traditional remedy that continues to inform and adapt in an era of scientific medicine.