America’s first anatomy riot started with a crass joke.

One afternoon in April 1788 a medical student was dissecting a woman’s body in a lab at New York Hospital. Suddenly, he realized he wasn’t alone. A gang of street urchins had gathered at the window outside—gaping wide-eyed at a real-life dead person.

This annoyed the student, who wanted to work in peace. So to spook the boys, he reportedly grabbed the cadaver’s arm and waved it at them, hollering, “This is your mother’s arm. I just dug it up!”

Har har. Unfortunately, one of the boys had indeed just lost his mother, and he ran home to his father bawling. The father in turn grabbed a shovel and marched out to his late wife’s grave. He found exactly what he expected inside it—nothing—and he was furious.

He wasn’t the only one. Hundreds of other New Yorkers were every bit as angry with the hospital’s doctors. Folks were sick and tired of abuse at the hands of scientific body snatchers.

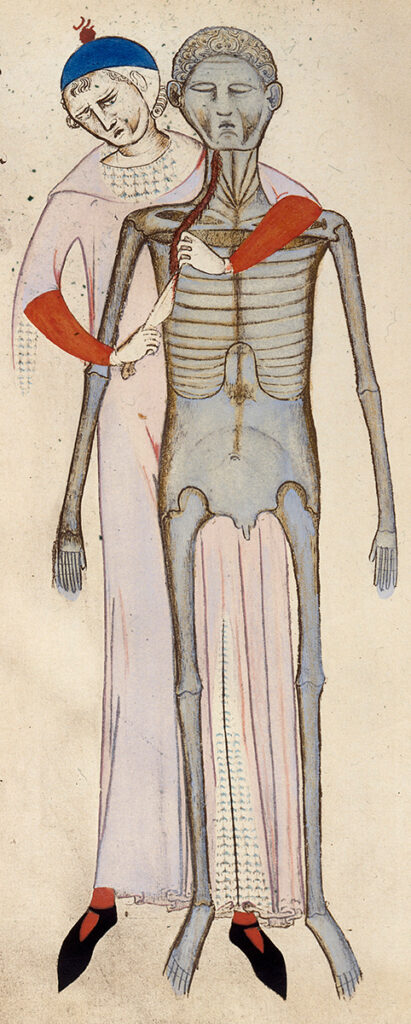

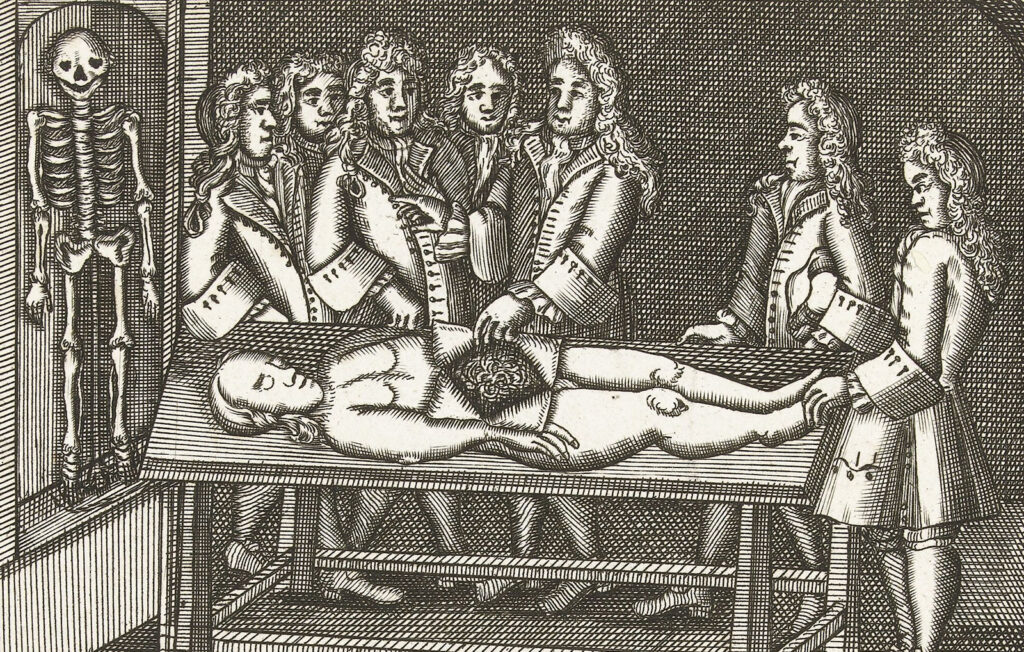

The roots of this abuse trace back to the United States’ former ruler, Great Britain. Many in Britain feared dissection after death would leave their bodies mangled on Judgment Day, when God would raise the dead. Britons also viewed dissection as shameful—a naked body lying there, poked and prodded. So government officials banned human dissections, offering just a few executed criminals per year to medical schools, far short of the number needed.

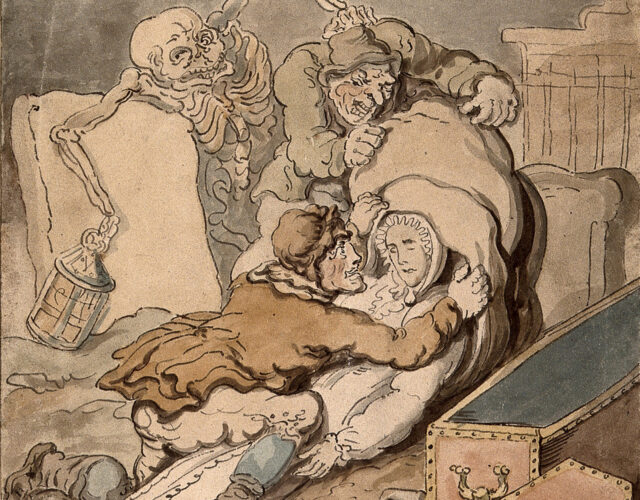

Given the lack of bodies, British anatomists felt they had no choice but to rob graves. Sometimes they enlisted their students as accomplices, swearing them to silence at the beginning of the semester. Whenever bodies were needed, the students would liquor up and, in what one observer called “wanton sallies of excess,” would storm the local churchyard to unearth fresh corpses. To them it was all a ghoulish game.

Other anatomists outsourced the work to professional grave robbers. The best of these so-called resurrectionists could expose a coffin and pull the body out in 15 minutes. They’d then schlep it across town, slip into an alley, and knock softly at the local anatomists’ back door. They typically got £2 per body, about $250 today. The money was so good that in one notorious case in Edinburgh two fellows named Burke and Hare started murdering lodgers at the latter’s boardinghouse and then selling the bodies for cash.

The odd murder aside, the British police mostly looked the other way with body-snatching. Officials knew budding doctors and surgeons needed bodies for training. And it was easy for officials to turn a blind eye when it wasn’t their loved ones going missing. Rich families could afford grave-robbing deterrents, such as underground iron cages called mortsafes that surrounded coffins or even private guards to watch over their loved ones for the week or two it took a body to putrefy. The poor had no such safeguards.

The United States inherited many British traditions, including the popular prejudice against dissections and the medical penchant for robbing graves. And just as on the other side of the pond, the poor suffered the consequences. The hardest-hit groups were American Indians, black people (both enslaved and free), and German and Irish immigrants.

By 1788 hatred of medical researchers was widespread in New York City. Now we don’t know for sure whether the medical student who waved the cadaver’s arm had actually stolen the boy’s mother. Perhaps someone else had, or perhaps the body was missing for another reason.

The boy’s father didn’t care: he wanted someone, anyone, to pay. And when he proposed storming the hospital to exact revenge, he found plenty of allies willing to join him—men who’d had the bodies of their own wives go missing, or of their sons or aunts, or who were simply sick of being exploited. Hundreds of people quickly gathered to march on the hospital.

When they arrived, the doctors and anatomists panicked. Most fled on foot; one climbed inside a chimney. The mob occupied the building, dragging equipment and specimens into the street to smash or burn. The rioters also recovered several bodies in various states of decay and reburied them.

Trashing the building didn’t slake the mob’s anger, however. In fact, their numbers swelled overnight, and the next day several thousand marched on a medical building at Columbia College (today Columbia University). Alexander Hamilton himself stood on the steps and begged them not to destroy it.

In the meantime New York mayor James Duane had jailed several doctors for their own safety since the prison was the stoutest building in town. But the mob wouldn’t be deterred, and soon 5,000 people had gathered outside. They smashed windows and tore down a fence, howling, “Bring out yer doctors!” At dusk the terrified mayor finally called in the militia. He begged local political leaders to come and help restore order.

Among the leaders called in was John Jay, future Supreme Court justice and future governor of New York. His pleading did no good. What did a blueblood like him know about having his loved ones’ graves robbed? Someone flung a rock at him, cracking his skull.

Another of the leaders called in—the army general and Revolutionary War hero Baron von Steuben—got beaned in the head with a brick. As von Steuben staggered back, bloody and dazed, he reportedly called on the mayor to have the militia fire.

Now technically this wasn’t an order. But the soldiers were already spooked and didn’t need any more encouragement. When they heard the word “fire,” they leveled their rifles and opened up on the crowd.

Suddenly, warfare erupted in the street. The rioters tried to hold their ground, but the soldiers’ firepower quickly overwhelmed them. The exact number of casualties is unknown, but by some reports 20 people were lying dead in the street by the time the smoke cleared and the mob had dispersed. The riot had started over one corpse and ended with many more.

The New York riot was hardly an aberration. At least 17 American anatomy riots took place before the Civil War—in Connecticut and Boston, Cleveland and Philadelphia, Baltimore and St. Louis. Eventually, in response to this violence—as well as continued pleading from doctors for more bodies to dissect—most states passed so-called anatomy acts, or “bone bills.” These bills allowed medical schools to secure unclaimed bodies from hospitals and poorhouses.

But if the anatomy acts helped quiet the popular fury, they still seemed ethically dubious to many people, even back then. Once again the burden for supplying bodies for scientific research fell almost exclusively on the poor and indigent. It wasn’t the well heeled or well connected who were dying unclaimed in poorhouses.

Eventually the voluntary donation of bodies eliminated the need to use unclaimed corpses. Philosopher Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, became the first person to donate his body to science in 1832, in part to lessen the stigma of dissection. His good deed didn’t convince many at the time, but the world had come around to Bentham’s thinking by the mid-1900s. Today, most bodies dissected in medical schools are gifts.

Nevertheless, schools still struggle to find enough. One analysis from 2016 concluded that New York City medical schools fell 36 bodies short of the 800 needed. In other states the shortfall was closer to 40%. And worldwide, countries such as India, Brazil, and Bangladesh face even bigger shortfalls. Nigeria has close to 200 million people, yet some medical schools there get no donations. To make up for shortages latter-day resurrectionists are digging up buried bodies or swiping them from funeral pyres and selling them internationally on the “red market.”

The story of body snatching in medicine is often painted in certain terms—those poor doctors and scientists trying to push science forward while fighting the ignorance and superstition of the masses. That’s true to some extent, but there’s another side to the story.

However unlearned the masses were, they knew the scientific elites were exploiting them, treating them as nothing but bags of blood and guts. And there are uncomfortable echoes of this exploitation today. In the past few decades, drug trials, archaeological expeditions, and genetic screenings have all caused public outcry in developing countries. In some cases people gave their bodies to science in a literal sense and watched scientists build careers on their backs, without benefiting much themselves. Things get especially testy when the scientific results undermine ancient lore and upend people’s views of their past. There’s a growing consensus among researchers that it’s unethical to put the pursuit of knowledge above the people who made that knowledge possible.

Ultimately, we don’t know whether the cadaver who sparked the New York riot in 1788 was that boy’s mother. But she was somebody’s mother or somebody’s daughter or somebody’s friend. The medical student meant no harm in waving the arm. He just wanted to get back to work. But to those on the outside looking in, his little joke seemed more like a matter of life and death.