What is it about a loaf of homemade bread that’s so appealing? Is it the loaf itself—the golden surface crackling between your hands, the steam that rises from its center? Or is it something in the process: the gentle rhythm to kneading, the elastic give-and-take of dough, the sense of sinking into the moment? It might be the sense of accomplishment—that moment when the flour is dusted away and the kitchen smells rich and yeasty. Or maybe it’s the breaking of bread, the sharing and nourishing, that touches us most deeply.

There are plenty of reasons why homemade bread feels like the ultimate comfort food, especially now that “stress-baking” has become a way of life for many socially distanced Americans. Our social media feeds are punctuated by images of rustic homemade sourdough loaves, tantalizing quarantine cookies, and the occasional baking “fail.” In the high-anxiety environment of the coronavirus pandemic, these traditional and comforting—but time-consuming—methods of food production have abruptly risen in visibility and importance. Their benefits are easy to understand. Amid uncertainty, cooking for yourself or your loved ones creates tangible results; and with more time spent in our own kitchens, the slow processes of rising, proofing, and maintaining dough “starters” can become pleasurable exercises in mindfulness, keeping our thoughts in the present moment.

If quarantine has driven you to experiment with sourdough starter, you’re in venerable company. Pliny the Elder, a 1st-century Roman polymath, described methods used by bakers to make their sourdough-like starter in his Natural History:

Our species’ relationship with starters, and specifically with the yeasts that power them, goes back even further, to prehistory. Leavened bread—as opposed to flatbreads—likely emerged in ancient Egypt, which was also a center for early beer brewing. (Egyptian workers were often paid in bread and beer.) Yeast was considered such an important part of the ancient diet that the 2nd-century physician Galen, best known for his theory of the bodily humors, claimed that “whatever is completely without yeast is of use to no one.”

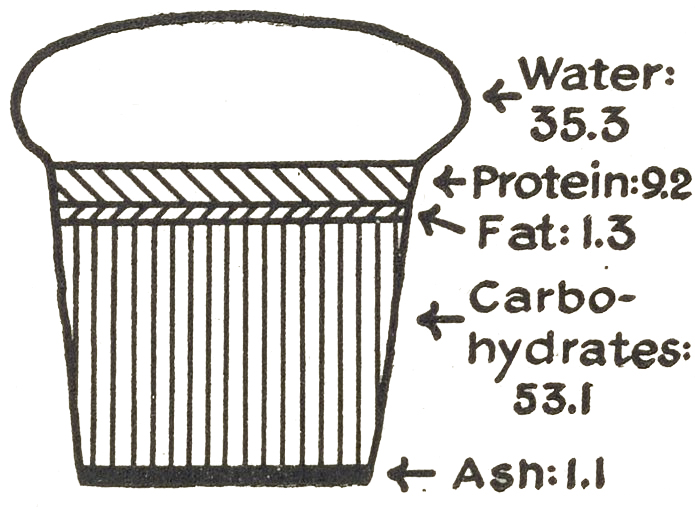

But leavened bread is more than a tasty throwback: it’s a reminder that cooking is chemistry. Baking is part of a complex system that includes chemical and thermal reactions, biology and bacteria—a system that modern foodways have largely disconnected us from. Eating store-bought bread doesn’t require us to understand the reactions happening in our mixing bowl. But the more we bake, the more we understand the actions and contributions of each individual ingredient, the importance of measurement, the rigor of process, and even the role of documentation: all elements of scientific inquiry. We’re actively learning and experimenting and in the process reclaiming once-common knowledge through our problem-solving.

We need look no further than our ancient friend yeast for an example of this process. Recent shortages of commercially processed yeast—the domesticated strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae—have led more-experimental home bakers to seek out “wild” yeast as their leavening agent. These single-celled organisms consume sugars and excrete carbon dioxide and alcohol as by-products, meaning that they are perfect leavening agents in bread baking and a source of natural fermentation for beer and wine. Wild yeast is present in our environment on a host of different surfaces—grains, fruit skins, and even human skin. Harvesting yeast can be as simple as leaving a bowl of flour and water on a kitchen counter. Naturally occurring yeasts are thought to lend food and drink more complex flavors and even a characteristic tang, hence the term sourdough.

Pliny’s note about using starter left over from bread “made the day before” reminds us that baking bread was a daily chore in a world without refrigeration. Most bread baking in ancient Rome was done in communal or commercial ovens. Working-class Romans, especially city dwellers, didn’t have kitchens: they lived in cramped, multistory apartment buildings called insula. Quickly and cheaply constructed from timber frames, insula had a nasty habit of catching fire and collapsing, and were therefore built without kitchens, ovens, or fireplaces. Romans grabbed their daily bread at bakeries and snagged heartier fare at thermopolia, or hot-food stands. Archaeologists have found numerous thermopolia in the preserved ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum, identifiable by their distinctive long concrete counters with circular depressions, designed to keep cooked foods warm; the setup was not unlike a modern buffet line. These market stalls sold roasted meat, baked cheeses, or hearty lentil stews: antiquity’s answer to fast food.

In medieval and early modern Europe bread was a core dietary staple for both rich and poor, but making it remained the province of professionals. Few bread recipes were recorded during this period; most chroniclers of domestic life assumed their readers would buy, rather than bake, their daily bread. Not until the 17th century did recipes appear in print, with one of the first found in Gervase Markham’s The English Huswife, published around 1615.

Since beer and bread were two of the most important foodstuffs, they were widely regulated. Much of our surviving knowledge of the breads sold and eaten during this period come from assize laws, which set standards for quality and weight and capped the price at which loaves could be sold. In England an assize statute introduced around 1266 identified four primary types of bread—Simnel, Wastrel, Cocket, and Treet—that were ranked by weight, lightest to heaviest, as well as by quality, coarsest to finest. Much like the assize laws, Markham names three primary categories of bread, but he also indicates their typical consumption by social class. A coarse brown bread made with peas, rye, and barley flour was described as suitable for peasants and laborers; next came a more refined bread made of wheat flour, intended for middle-class merchants and their ilk; and finally an extra-fine, fluffy white bread, which was reserved for nobility . . . and racehorses. (Markham’s culinary expertise was apparently matched by his fame as a horse trainer.)

Before the 18th century, standards for measurement varied widely between regions and industries, and most written recipes used comparative references to size and shape rather than exact weight or volume. A recipe might call for “a lump of butter the size of a thumb” or “a wedge of cheese two fingers wide.” Likewise, without timers or temperature dials, many recipes relied on their readers’ knowledge of familiar songs or prayers and their long experience with managing cooking fires. Modern cooks would be stumped by instructions to “recite ten verses” over “ash-smothered coals,” while a 17th-century reader wouldn’t have batted an eyelash. The common measuring cup, a cornerstone of the contemporary baker’s world, didn’t make its appearance until 1896. Fannie Merritt Farmer, a pioneer in late-19th-century American domestic-science education, popularized the modern cup and spoon system as well as the idea of “level” measurement, meaning that containers of ingredients were to be leveled off rather than heaped, which created greater specificity and uniformity for her recipes. Standard measurements combined with other innovations, such as baking powder (invented in 1843) and the electric stove (exhibited at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair), meant that home baking was primed for a major boom.

Bakers’ changing tools and recipes were also shaped by changing ingredients. Once again, our loyal partner in leavening—good old yeast—was at the center of things. Before the 19th century many bakers harvested their yeast from barm, a yeasty foam layer that formed on top of fermenting beer vats. But changes to brewing technology decreased the availability of barm and pushed bakers to cultivate their own strains. Around 1850, Viennese bakers developed a form of “press” yeast that was skimmed from a fermented dough starter, then either preserved as a yeast “cream”—a mix of the yeast and its liquid growth medium—or rinsed and pressed into yeast cakes that could be revived with flour and water. (In that same decade, the famed French pathologist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur revealed that yeast are in fact living, single-celled organisms whose active digestion is key to fermentation. Until his discovery most scientists had assumed that decay produced fermentation; Pasteur’s microscope revealed that yeast’s breakdown of sugar and starch and production of carbon dioxide relied on the action of living cells rather than the decomposition of dead ones.

The Vienna process gained popularity in the United States during the 1876 Centennial Exposition when Hungarian-Jewish immigrants Charles Louis Fleischmann, his brother Maximillian, and their business partner James Groff exhibited a model bakery under the banner of the Fleischmann Yeast Company. The same company’s Active Dry Yeast, a shelf-stable granulated form invented during World War II, quickly became a best seller thanks to its longer shelf life and ease of use. Fleischmann’s laboratory-cultivated yeast strains were selected for their consistent performance, sweeter taste (as compared to barms or starters), and quick rising action. Packaged yeast freed both professional and home bakers from the need to maintain starters, but it also led to a major change in flavor: the new strains lacked the characteristic sour tang of wild yeasts. The specialty loaves we now call sourdough are much closer to what 19th-century Americans called their daily bread.

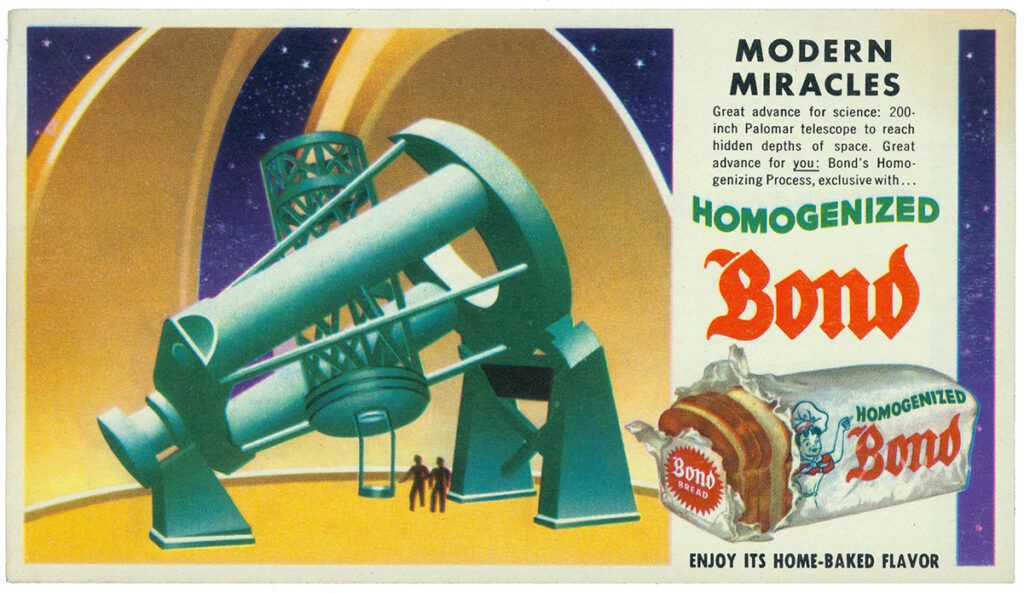

Not everyone shares the need to knead, and cooking has never been just a pleasant hobby. Especially for poor women, servants, and enslaved people, it was and, in some cases, still is an endless drudgery. Our current fad for slow, thoughtful, demanding cooking methods is in a sense an ironic contrast to the 19th and 20th centuries’ emphasis on labor-saving kitchen devices and preprocessed foods. While canned goods had been cutting meal preparation time since the 1860s, the rapid expansion of supermarkets between the 1940s and 1950s meant that American consumers (at least of the middle-class, suburban variety) were increasingly buying nationally branded processed foods, such as Swanson’s TV dinners. These frozen meals were introduced around 1953 and could be heated and eaten in their own disposable, oven-safe tray.

While the ancient Romans may have invented takeout, 1950s and 1960s entrepreneurs perfected it, applying emerging industrial technologies—chemical preservatives, assembly lines, and high-volume pressure cookers—to fast-food production. This era’s bread of choice? Plastic-wrapped, pre-sliced white bread made from bleached flour—Wonder Bread. The bread first appeared in 1921, but its sales boomed after a 1940s advertising campaign promised consumers added nutrients, such as thiamin and riboflavin. (These nutrients exist in whole-grain flour but are stripped out by the bleaching process.) White bread’s success was fueled by a mix of convenience and marketing, as well as an undercurrent of American prejudice. Traditional, immigrant-run bakeries were often falsely portrayed as less sanitary than the gleaming factories churning out shrink-wrapped, snowy-white loaves.

White bread became a lightning rod for the counterculture movements of the 1960s and 1970s, not only for the food’s lack of nutritional value and its industrial origins, but also for what it represented: homogeneity and conformity. Quicksilver Times, an underground activist magazine, called on readers to reject corporate food along with corporate ethics: “Don’t eat white; eat right; and fight.” The growth of the environmental movement, along with increased American awareness of global food traditions, also led many to seek out unprocessed, organically produced “hippie foods,” such as tofu, flax seed, and ancient grains, as well as—you guessed it—homemade whole-wheat bread. But after almost two decades of dominance by store-bought bread, many young freethinkers found themselves making homemade brown bread that was as dense as a brick and just about as tasty. Part of the problem lay in the core difference between white and whole-grain wheat flours: wheat bran, when not removed during the refining process, cuts through the longer strands of gluten that form in dough, leaving the finished loaf less chewy and airy. Enter 1971’s Tassajara Bread Book, written by Edward Espe Brown, a young cook living at a Northern California Zen monastery. Brown’s best seller helped a generation rediscover a love for home baking and, through gentler kneading and longer rises, create a softer, chewier brown bread.

The resurgence of homemade brown bread during the 1970s’ social upheaval and economic crisis has parallels to the ascent of sourdough as a pop-culture touchpoint during the social isolation of the coronavirus lockdown. Countercultural bakers were looking for connection: connection to their ingredients and their origins (the closer to nature the better) as well as connection to a greater community of fellow bakers and eaters and their historical and cultural memories.

Can engaging in a process that would have been recognizable to our great-grandparents or our great-great-great grandparents reassure us of some basic social continuity? Maybe. And maybe mastering those processes and regaining some of that technical knowledge—lost long ago in the supermarket aisles—is one of the reasons pandemic bread making feels so rewarding right now. We’re not only feeding ourselves, we’re increasing our understanding of how the world works, one loaf at a time.

Of course, baking can’t solve all our problems. The politics of food are as fraught as ever, and not everyone is lucky enough to have the time, energy, or capacity for homemade sourdough. But this moment reminds us of the resilience and elasticity of dough, the toughness in those glutenous bonds: how it’s kneaded and rolled and pounded flat, how it rises back again and again. In baking, as in science, as in life, we learn as we go. And we can only hope that tomorrow we’ll know more than we do today.