In 1629 Dutch merchant Francois Pelsaert wrecked his ship on a coral reef near the coast of what is now Western Australia. While searching for fresh water he encountered a strange creature “about the size of a hare, [its] head resembling that of a civet cat; the forepaws are very short . . . resembling those of a monkey’s forepaw. Its two hind legs, on the contrary, are upwards of half an ell in length, and it walks on these only.”

This chimeric description was mostly ignored until Captain James Cook reached the east coast of Australia in 1770. Cook’s crew described hunting and eating the animal. Over the next decade several isolated reports of the beast arrived in Europe, but naturalists were hesitant to believe them. Some witnesses even described the animal as having two heads, one protruding from its stomach. It wasn’t until explorers brought complete carcasses back to Europe that Western scientific communities accepted the kangaroo and wallaby as real creatures.

As Western countries industrialized throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, their governments and industries looked to remote corners of the world in search of resources and markets. Expeditions to find rubber, whale oil, and minerals led to the discoveries of strange creatures, both living and long dead, and new peoples with strange customs. Cook returned from his first voyage to the Polynesian islands with tales of ink-covered people. (The word tattoo comes from the Tahitian language.)

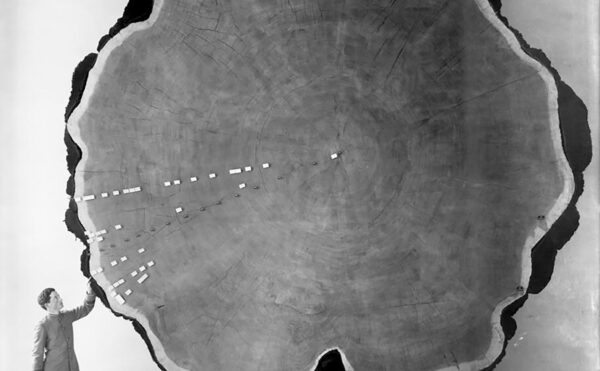

Strange things were being found close to home too. Footprints of what appeared to be giant birds were discovered in the Connecticut River Valley; enormous fossils, at the time classified as ancient lizards, were dug up in the American West. With evidence of these great beasts being uncovered in American pastures and farmland, what ordinary person could dismiss sailors’ tales of sea monsters and mermaids? Such an environment of constant discovery and wonder was ripe for showmen and hucksters, and no one exploited these circumstances quite like Phineas Taylor (P. T.) Barnum.

Barnum, known today for traveling circuses, grew up in Bethel, Connecticut, not far from where the first dinosaur tracks were uncovered. A born salesman and showman, at age 25 Barnum created his first true sensation (and controversy) by purchasing and traveling the Northeast with a slave named Joice Heth. Barnum claimed Heth was George Washington’s nurse. Few scientists believed that the blind and paralyzed old woman was actually 161 years old, but Barnum still made nearly $1,000 from ticket sales every week. He used that money to purchase Scudder’s American Museum in New York City in 1841 and renamed it Barnum’s American Museum. He filled it with thousands of strange objects and bizarre performers.

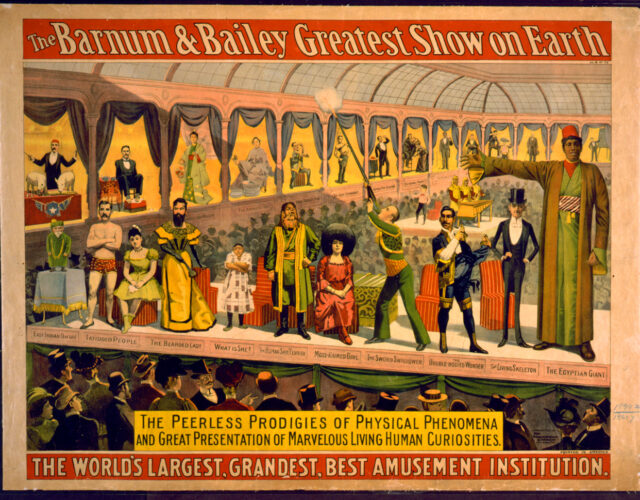

Barnum’s genius was being able to reel in both suckers and skeptics. Some came believing his spectacles were real, while others came to confirm their suspicion that it was all fakery. Either way Barnum got paid. Barnum scattered real curiosities among the fakes to give his exhibition a whiff of plausibility, if not credibility. Visitors to the American Museum in the 1860s found Siamese twins presented next to Zip the Pinhead, purportedly the missing link between humans and monkeys.

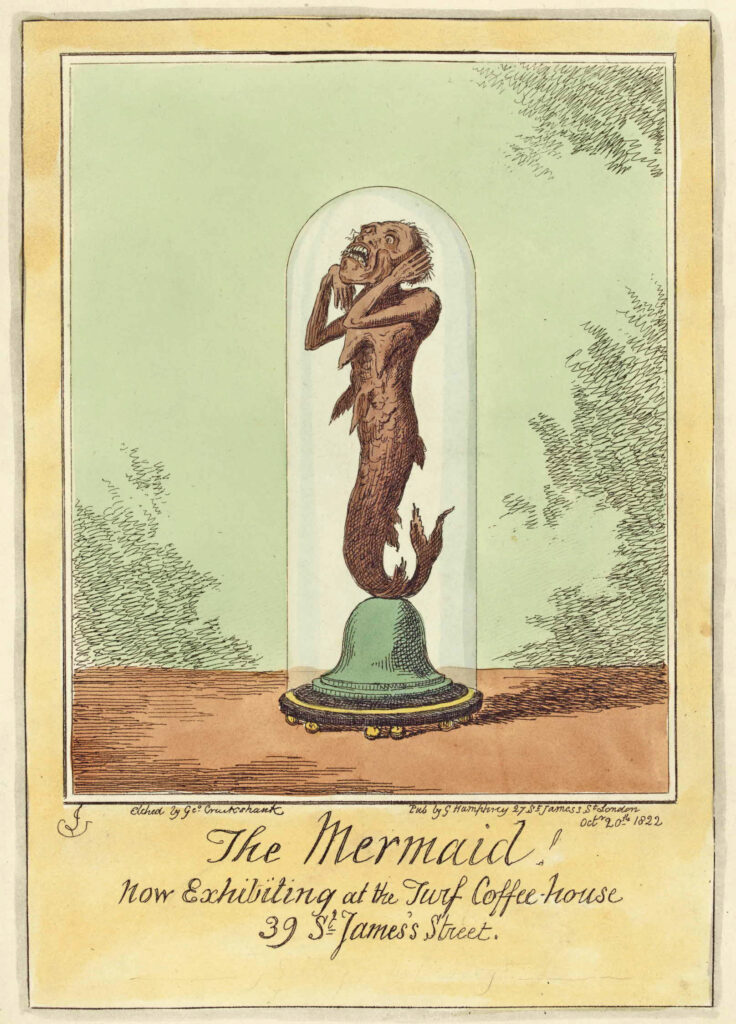

In the summer of 1842 Dr. J. Griffin of the Lyceum of Natural History in London challenged Barnum’s monopoly on the incredible. Newspapers around the country announced Griffin’s discovery of a mermaid specimen found on a Fijian beach. Soon the public was in a frenzy to see the thing. Griffin rented a hall on Broadway in New York where he displayed the artifact and lectured on its discovery. Soon the crowds grew too large, and so Griffin teamed up with Barnum and moved the mermaid into the American Museum. Visitors who encountered the mermaid were both disgusted and amazed. Instead of the lounging, bare-breasted mermaids found in advertisements for the exhibit, viewers were confronted with a dead, dried, and hideous specimen. Twisted into an eerie posture with hands raised and mouth wide open, it looked more like a monkey-fish than a mermaid. Still, it was like nothing anyone had seen before, and it inspired both skepticism and wonder. That some visitors doubted the mermaid’s authenticity mattered little to Barnum. The bigger the controversy, the more press his museum received, and the more tickets he sold.

Griffin’s lectures resembled the popular scientific lectures of the day, such as chemist Michael Faraday’s lecture series at the Royal Institution in London. Faraday invited the audience to see chemistry up close and demonstrated how seemingly mundane objects—such as burning candles—were actually complex and fascinating scientific systems. Griffin applied this approach to his mermaid lectures to give his hoax legitimacy.

We know the Fiji mermaid was a hoax, but in the mid-19th century sailors still regularly claimed to spot mermaids. Even Christopher Columbus wrote about seeing mermaids when sailing near the coast of Haiti in 1493; and as recently as 2009, residents of Kiryat Yam, Israel, claimed to see a mermaid on a beach at sunset, although this was probably a publicity stunt to boost tourism. Columbus’s reports were likely a case of a weary crew mistaking a manatee for a womanly creature.

Of course, Griffin was not an intrepid explorer like Columbus, or even a scientist. He and his scientific institution were as fabricated as his mermaid. Barnum created the character of Griffin and had his collaborator Levi Lyman play him. Lyman traveled the country as Griffin, showing his “discovery” to newspaper reporters and the curious. The origins of the Fiji mermaid, though, are murkier. According to Moses Kimball, who leased the mermaid to Barnum, a Japanese fisherman created it in 1810 by stitching the head and torso of a monkey to the tail of a fish. The fisherman later sold the mermaid to American sailor Samuel Barrett Eades for $6,000, who passed it down to his son, who then sold it to Kimball.

More hoaxes followed in the wake of the Fiji mermaid’s success. George Hull commissioned and then buried a humanoid statue on a relative’s farm in Cardiff, New York, in 1869; Hull’s creation was “discovered” a year later. Most scientists immediately recognized it as a statue, though some credulous spectators believed it to be a petrified giant from a time described in the Bible. So many dinosaur fossils and Native American artifacts were being unearthed in the late 1800s that some scientific types, including the New York state geologist, believed the statue to be, if not a petrified giant, certainly an authentic artifact from an ancient culture. Hull eventually came clean, ridiculing the naïveté of those who believed his hoax, but not before making a small fortune from the sale of tickets to view the “Cardiff Giant.”

Why did so many pay to see Hull’s and Barnum’s attractions? I was a sucker myself once. During summer vacation in high school I was driving through central New Hampshire and stopped at a county fair. Nestled between a rusted Ferris wheel and a cluster of carnival games was an unmarked tent presided over by a man wearing a top hat and doing his best Barnum impression. For only $5 I could see the “Strange Thing.” I watched as people paid and disappeared into the tent only to come out the other side wide-eyed and whispering to each other.

A few moments later I handed over my money. I was a skeptic and had decided that once I could prove the strange thing a hoax, I would warn people away. I passed over the threshold into darkness. A dirty rope railing guided me to a small glass box sitting on a pedestal in the center of the tent. The glass was smudged, but I could see a tiny creature resting on a bed of sand. Its face was shriveled, and it had hairy arms and fins. The creature gazed back at me, and for a brief moment a shiver crept up my spine. Logic soon took over, and I saw nothing more than a poorly constructed sculpture. Much later I realized the strange thing was a replica of the Fiji mermaid.

I did not try to stop people from paying the hoaxer. He did not promise a living mermaid, only a strange thing, and the thing I saw was certainly strange. Each visitor could choose to believe or not. In a world of kangaroos and dinosaur bones, who can blame someone for wanting to?