Distillations magazine

A Game of Cat and Mouse

A predator stalks Marion Island, and it weighs less than an ounce. Scientists are racing to stop it.

Distillations articles reveal science’s powerful influence on our lives, past and present.

Parcelas de ajonjolí

Una diáspora en veintiún movimientos.

This Bag Is Not a Toy

The plastics industry’s early scare.

Venom in His Veins

Red the World Over

How a tiny cactus parasite called cochineal became one of the Spanish Empire’s most lucrative commodities.

Good Living

Does nature have rights? In 2008, Ecuador said yes. Doing so forced a reckoning with the country’s mining past.

Madame Microwave

Meet Jehane Benoît, Canada’s grande dame of culinary nationalism.

Politically Charged

How shady car battery additive AD‑X2 sparked a showdown between the U.S. political and scientific establishments.

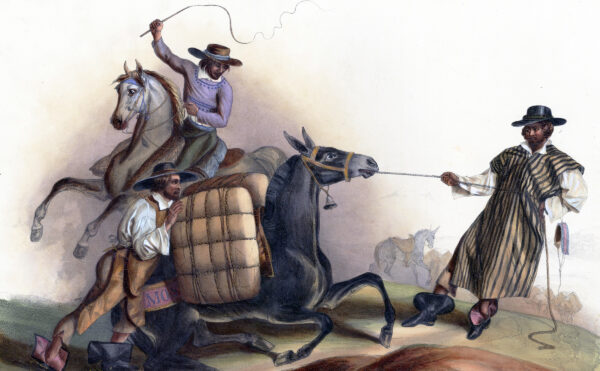

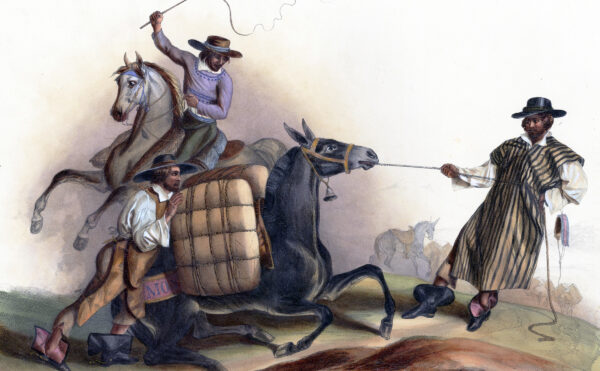

Mule Power

Unpacking empires and diaspora in Mexico and the United States.

Mulas de fuerza

Desempacando imperios y diáspora en México y Estados Unidos.

Ed Pendray and the Science of Tomorrow

A PR man’s pitch for science.

Something Old, Something New

Humans owe a huge medical debt to horseshoe crabs. Now there’s an opportunity to pay it back.

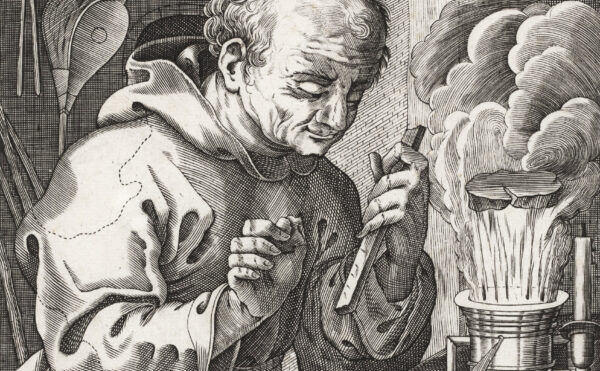

Holy Smoke

The monks, nuns, and friars at the forefront of alchemy in early modern Europe.

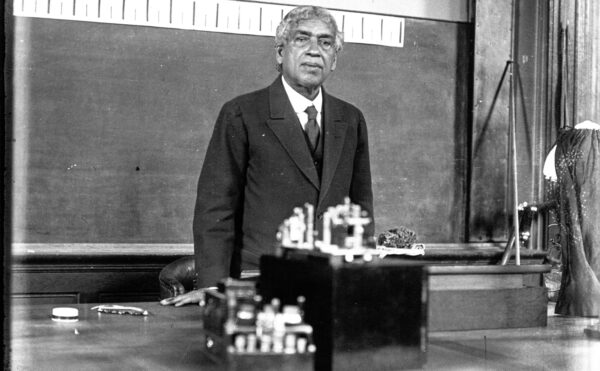

The Thinking Plant’s Man

Jagadish Chandra Bose and the contentious search for plant intelligence.

Disorderly Persons

What are laws against fortune-telling really meant to do?

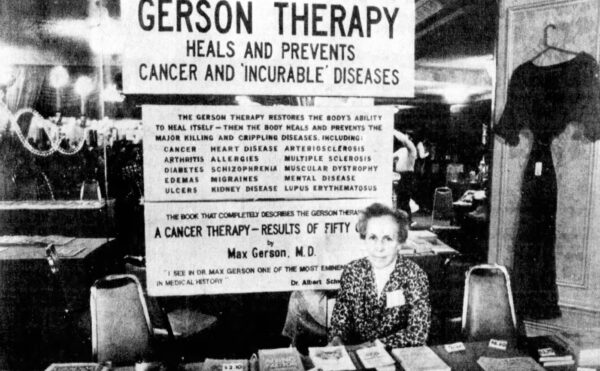

Gerson’s Magic Bullet

Why have so many rejected established cancer therapies for juice cocktails and coffee enemas?

The Ingenious Arctic Cooking Pot

Rediscovering the clever chemistry behind a ceramic tradition that had all but vanished.

The Trials of Lavoisier

Tracking the Reign of Terror through a revolutionary chemistry journal.

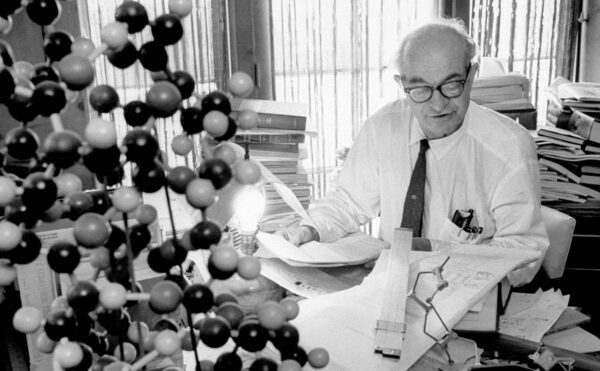

Linus Pauling’s Vitamin C Crusade

The path to a dubious cure.