In 1806 President Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to a doctor in England. The president was effusive, stating that he was “rendering . . . a portion of the tribute of gratitude due to you from the whole human family. Medicine has never before produced any single improvement of such utility. . . . You have erased from the calendar of human afflictions one of its greatest.”

The president’s gratitude was directed at Edward Jenner, who in the 1790s had shown that inoculation with cowpox almost always protected people from smallpox, a far more serious and sometimes lethal disease. His discovery was widely hailed by enlightened physicians and intellectuals. Parliament awarded Jenner £10,000, followed five years later with an extra £20,000. Jenner’s techniques were adopted in many countries, including the fledgling United States. In his letter Jefferson predicted that “future nations will know by history only that the loathsome small-pox has existed and by you has been extirpated.”

Yet this miraculous, workable, and effective preventative did not become routine, not even for children. The incidence of smallpox naturally ebbed and flowed, and people sought out Jenner’s vaccination only during epidemics. At such times the huge increase in demand could lead to a shortfall of the vaccine. Additionally, the vaccine might be contaminated with other diseases, such as syphilis, a possibility that terrified people and dissuaded them from getting inoculated.

These factors limited general adoption of smallpox vaccination for more than a half-century until a largely unheralded innovation resolved the problems. The innovators themselves are hardly known, even to historians, who have overlooked a technological revolution.

Today vaccines are produced on an industrial scale in factories and laboratories, but until the 1870s any doctor wanting to vaccinate a patient against smallpox had to collect fresh, virus-laden pus or a dried scab from someone recently vaccinated. Unsurprisingly, access to scabs and sores was hit or miss, given people’s comings and goings and the limited window in which the vaccine would be fresh enough to be effective, not to mention a healthy person’s unwillingness to return to the doctor for a nontherapeutic procedure. Authorities occasionally relied on recently vaccinated soldiers, who were required to present their sores for extraction of pus. Unfortunately, military men had often been exposed to other diseases, leading to accidental transmission of syphilis or erysipelas.

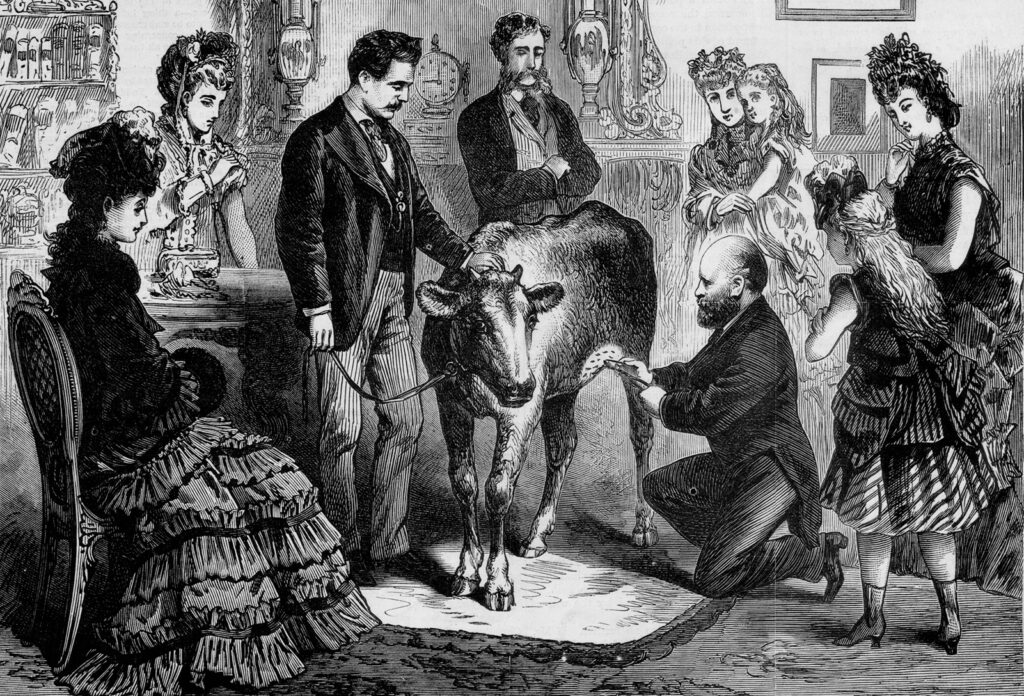

For decades after Jenner’s breakthrough few efforts were made to use cowpox inoculant taken directly from cattle, perhaps because Jenner’s vaccine came from cowpox sores on the arms and hands of infected milkmaids. Then, in Italy around 1840, Giuseppe Negri of Naples successfully used bovine material to vaccinate people. The new approach was reported at medical congresses, but it was not seriously considered by the medical profession at large until 1864, when Gustave Lanoix and Ernest Chambon brought a calf infected with cowpox from Naples to Paris with the aim of establishing a vaccine service. Within a few years one of their calves was being used at the Academy of Medicine. The juxtaposition of well-dressed physicians and fancy architecture with a docile heifer made the event newsworthy. One heifer could provide enough virus for thousands of vaccine doses over a few weeks, and a small herd would allow for vaccination on demand for any city facing an epidemic. And patients no longer risked simultaneous infection with other human diseases.

Chambon relocated to the United States for a while, opening an office at 120 Fort Greene Place in Brooklyn, at the time the country’s third most populous city, where he garnered even more publicity.

Thanks to the advocacy of Chambon, American physician and smallpox expert Henry Martin, and others, health departments and entrepreneurs quickly established “virus farms” across the United States and Canada in the closing decades of the 19th century. These novel establishments—among the first production facilities for biologics to be inspected and approved by the FDA—provided a steady, copious, and safe supply of the life-saving vaccine material, the use of which in turn produced stunning results. Nearly 250,000 people were vaccinated in Brooklyn in 1894, and in 1902, 800,000 New Yorkers—almost a quarter of the city’s population— were inoculated.

By the 1920s, vaccination programs had almost completely eradicated smallpox in the United States.