David K. Randall. Black Death at the Golden Gate: The Race to Save America from the Bubonic Plague. W. W. Norton, 2019. 373 pp. $27.

For many people the words black death or bubonic plague evoke the medieval world, specifically the 14th-century pandemic that killed millions throughout Asia, Africa, and Europe. Or perhaps it calls to mind 17th-century London, where an infamous outbreak felled 20% of the population between 1665 and 1666, prompting diarist Samuel Pepys to write about bodies piling up in the streets and the endless tolling of funeral bells. But those were just two of many plague epidemics during the past 1,500 years. In the 19th century, China, Hong Kong, and India endured devastating bouts as the disease circumnavigated the globe, moving from port to port. Then, at the turn of the 20th century the dreaded plague found its way to the United States, where obstinate politicians and power brokers, concerned more about commerce than public health, tried to pass off evidence of the plague as “fake news.”

In this way David K. Randall’s riveting history of this unfamiliar outbreak, Black Death at the Golden Gate: The Race to Save America from the Bubonic Plague, takes us into familiar terrain: arguments over media influence, government-supplied information, and the legitimacy of scientific research, particularly as it applies to medicine and the current vaccination debate. The author, a reporter at Reuters, scoured old newspapers and scholarly books and journals, parlaying that research into a straightforward narrative for nonspecialized readers. The result is edifying without being overbearing—a palatable book about plague. Many readers will find it a surprising—and hair-raising—chapter in American history, one that contains lessons of the “doomed to repeat it” variety.

In December 1899 the plague made landfall in a Hawaii still 60 years from statehood. After several deaths among Chinese immigrants the local board of health quarantined Honolulu’s Chinatown, trapping 10,000 residents within an eight-block space patrolled by armed guards. Many people, including some doctors, believed Asians were carriers of this strain of plague, writes Randall, a reminder of the extreme anti-Chinese sentiment of the time.

When the disease spread beyond the barrier to a white teenager who subsequently died, the panicked board turned to a more drastic solution—purification by fire—and burned down an apartment complex that had housed 85 Chinese, Japanese, and Hawaiian residents. The officials were attempting to re-create London’s Great Fire of 1666 but on a smaller scale. That fire was widely believed to have hastened the plague’s end while reducing most of London to ash. In Honolulu burning down a couple of buildings thought to harbor germs didn’t have the same effect. Though doctors had recently identified the rod-shaped bacterium Yersinia pestis as the source of plague, there was no consensus on how the disease spread. Nevertheless, Hawaii’s health officials remained undeterred. So as the plague claimed more victims, the officials responded by setting fire to more structures. In January a wayward ember sparked a chaotic, 18-day blaze, which finally stemmed the epidemic.

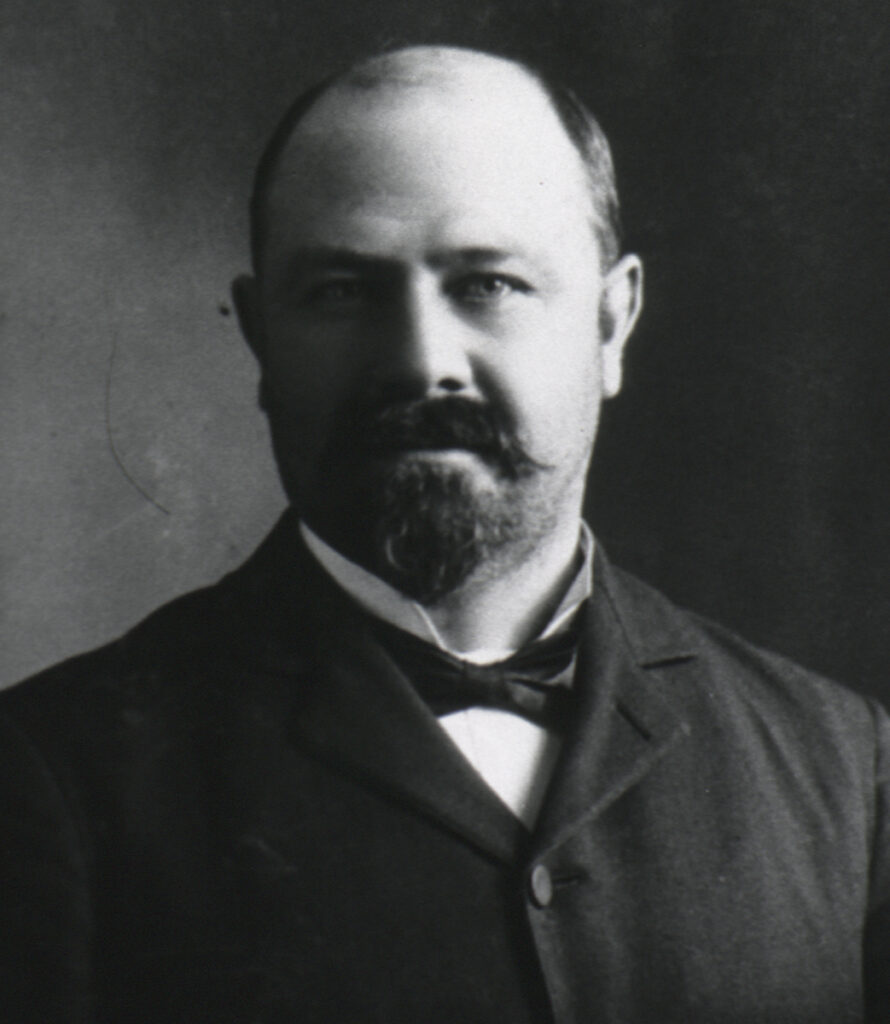

At least one American doctor was paying close attention to Hawaii’s plight. Joseph Kinyoun had been reassigned to San Francisco’s Marine Hospital Service only six months earlier. His boss, Surgeon General Walter Wyman, jealous of Kinyoun’s rising star in public service, had him shipped cross-country to run the nation’s largest quarantine station, which sounds impressive but wasn’t. Angel Island, in San Francisco Bay, was short of potable water, littered with garbage, and ill-equipped for medical research—a humiliating setting for a man who was the very definition of a lab rat. Kinyoun was a pioneer in the field of bacteriology at a time when many doctors had little faith that lab research could ever help patients. He knew that Y. pestis would somehow hop from Honolulu to San Francisco—what mattered was whether they had the resources to stop it in time, which he doubted.

Kinyoun was a prickly man, and he had already bristled when San Francisco’s board of health and its coroner had disagreed with him over the cause of death of two sailors. So when a Chinese immigrant named Wong Chut King died in March 1900 after showing signs of bubonic plague—specifically painful, swollen lymph nodes called buboes that appear in the groin or on the neck—Kinyoun and the board of health were again set for confrontation. City officials refused to wait on Kinyoun’s painstaking identification of the bacterium and quarantined 20,000 residents of Chinatown. One newspaper, calling the disease “largely racial,” informed its white readers that there was no cause for concern, adding that “the most dangerous plague which threatens San Francisco is not of the bubonic type” but instead “a plague of politics.” The San Francisco Chronicle likewise viewed the quarantine as a scheme by officials at the board of health to boost their budget appropriation. That corruption was rampant from the mayor on down was true, Randall writes, but it was also true that Wong had died from plague; Kinyoun’s lab results—and dead lab animals—didn’t lie.

As local officials played down the threat of plague to protect interstate trade and travel, city physicians also rebuffed Kinyoun’s professional opinions, reporters mocked him, and even Wyman, his lily-livered boss, caved to political pressure and withheld his support. But then more bodies began turning up, abandoned in alleyways and boardinghouses. The city responded with inspections in Chinatown that were at best demeaning and at worst violent. When these same officials came around with an experimental vaccine made with plague cells sourced from cadavers, many Chinese residents believed it to be an attempt to poison them, a fear that continues to underpin antivaccination movements, most recently in the United States (measles) and in Africa (Ebola).

Kinyoun continued to push for vaccination as well as health screenings for those leaving California by sea and rail. The Chamber of Commerce tried to dissuade Kinyoun through bribes and coercion, but he dug in his heels and as a result made lots of enemies. The press began referring to him as “Suspicious Kinyoun.” He even caught flak from the president of the United States, William McKinley, a man easily swayed by both congressional delegates and the owner of the San Francisco Call, a wealthy Republican influencer who wanted Kinyoun to stand down.

As the naysayers tried to control the narrative, the plague worsened, and a commission of local doctors verified Kinyoun’s findings. Meanwhile, California’s governor, along with steamship and railway executives, persuaded a group of newspaper editors to maintain a complete news blackout on the commission’s report while the city and state quietly agreed to fund a “full sanitation campaign in Chinatown.” Wyman, in cahoots with the crooked governor, had Kinyoun transferred out of the city.

But news of the plague had begun to leak, first in a medical journal, then in the Sacramento Bee, and finally in national newspapers. San Francisco’s papers remained silent, except for bashing bacteriology or insulting Kinyoun’s successor, Rupert Blue. The San Francisco Chronicle went as far as congratulating the city on refusing “the baseless allegations of the men who attempt to make the world believe that it is necessary to use microscopes to discover an epidemic.”

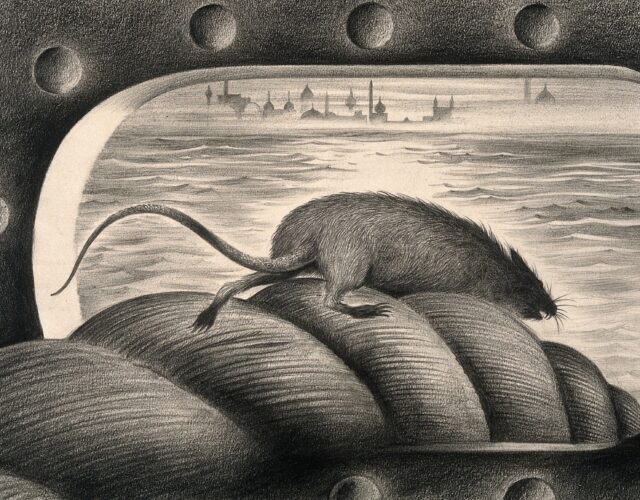

Blue was facing an uphill battle, but he approached the problem differently: instead of insulating himself he set up a lab in Chinatown. He talked to its residents and walked its streets, finding piles of rotting meat, sewage, and dead and dying rats. When a second white victim surfaced, Blue contemplated those rats. As Randall observes, “The link between a widespread die-off of rats and the arrival of plague has been obvious since antiquity,” but evidence for transmission by infected fleas jumping from dead rats to living humans was less than certain. At the time many physicians, including Surgeon General Wyman, didn’t accept the theory, believing instead that filth—urine and feces—was the primary vector of the disease.

Given such assumptions and a new mayor who vociferously denounced the board of health and any reports of plague, Blue did what little he could. He managed a citywide cleanup in 1903 that included soaking Chinatown’s cellars with carbolic acid, laying asphalt sidewalks, tearing down shacks and lean-tos, and trapping rats. Randall believes it unlikely that Blue knew about the work of Paul-Louis Simond, the French physician who had linked rat fleas to plague transmission in the 1890s; instead Blue concentrated his efforts on catching, killing, and dissecting rodents. This was, writes Randall, “the first time in American history that a federal health officer had focused on killing rats as a way to combat a crisis.”

The plague wore on slowly but steadily, with more than 100 deaths by early 1905, but then it seemed to disappear. Even the 1906 earthquake that leveled much of San Francisco and forced its citizens into unsanitary refugee camps failed to summon the dreaded disease. But in May 1907 the plague returned and claimed several white victims. Blue ramped up rat exterminations, dispatching as many as 13,000 in a week. He found that 1.5% of them were infected (2% was considered the tipping point for setting off a pandemic). A desperate Blue met with the owner of the city’s largest paper, the San Francisco Chronicle, and begged him to inform his readers about the plague and the role of rats. The publisher remained unmoved.

The apathy didn’t end there. The California State Medical Society decided it should, quite belatedly, organize a summit to discuss the threat of plague. Only 10% of its members showed up, and those who did merely passed a resolution calling on the mayor to back rat eradication. Only the threat of losing a visit from the Great White Fleet, a display of U.S. Navy battleships that would bring both tourism dollars and prestige to the city, finally got most of San Francisco’s bigwigs on board with funding Blue’s cleanup efforts.

The death toll for San Francisco’s second wave of plague reached 65, and yet when compared with the mass deaths in India or Hong Kong, the city had been fortunate. But why? The most common flea in the city was a Northern European species, Ceratophyllus fasciatus, which, when it bites, injects less bacteria from its gut into its host than does its Asiatic cousin, Pulex cheposis. “The slow spread of the disease—a phenomenon that led the city to doubt Kinyoun’s warnings and call the epidemic a fake ploy by corrupt health officials—had hinged on the stomach of a flea, a lucky quirk that spared an untold number of lives,” Randall writes.

Bubonic plague has never been fully stamped out in the United States. Infected rats and squirrels made their way out of San Francisco into greater California and beyond. When the plague turned up in a poor section of Los Angeles in 1924, the police quarantined 2,500 Mexican Americans, and, as in San Francisco, the press held off on confirming the facts. Latinos were fired from their jobs, their neighborhoods were cordoned off, and their homes were burned down. If any lessons about medical misinformation had been learned in San Francisco, Los Angeles seemed oblivious to them. The outbreak, which killed 40 people, was ultimately traced to one dead rat.

The rash of plague deaths in Los Angeles 95 years ago was the last of its kind on American soil, and while it’s true that each year about seven people in the United States still contract this medieval-sounding disease, modern medicine in the form of antibiotics and factual public health information can save us. If we let it. Recent history shows that when it comes to public health, disinformation continues to sway people, from the AIDS epidemic of the late 20th century to the antivaccination movement of the early 21st. Moreover, as in San Francisco during its plague years, reporting of contagious diseases can be lax when tourism dollars are at stake. Cuba’s Zika virus outbreak in 2017 may be a case in point.