Picture a visitor to an art gallery walking among landscapes of the French countryside, still lifes of bright oranges and blooming sunflowers, and Dutch portraits of long-dead patrons. She turns a corner and suddenly encounters an enormous Starbucks coffee cup. Is it a joke? Moving closer, she looks up at that unmistakable logo and plastic lid. She may dislike Starbucks coffee, or she may be a gold-card member counting down the days until pumpkin spice returns. Either way the result is an immediate, visceral reaction to the ubiquitous presence of an object usually destined for the trash, yet here elevated to a work of art.

This is pop art. By highlighting how commonplace, mass-produced objects inspire consumer fantasy, myth, and desire, pop art aims to destroy distinctions between high and low culture. Today the term most often evokes 1960s New York City and the iconic figure of Andy Warhol, whose deadpan public persona added intrigue to his Campbell’s Soup Cans and the Marilyn Monroes he silk-screened—over and over—until his images reached paradoxical fame and utter banality.

Today Warhol might be the icon of pop art, but it was British artist Richard Hamilton, an outsider to American culture, who first approached the country’s advertisements and consumer products with the same curiosity and criticism previously reserved for historical masterpieces. Instead of creating art from consumer images, as Warhol did, Hamilton considered how new synthetic materials were shaping society in the years after World War II. Materials like Poly-T, a refined polyethylene used to make Tupperware tumblers and sealable bowls, not only changed the way women stored leftovers; they also changed the way women socialized and earned money, inspiring the Tupperware party and its networks of female entrepreneurs and shoppers.

Hamilton observed the rising role of plastics in society and responded by creating artworks of contemporary life using synthetic materials. These materials were so “of the moment” and so new to art that Hamilton was uncertain whether his work would endure long enough to enter museum collections. Preserving such pieces was new territory.

Hamilton was an unlikely artist. Born into a blue-collar family in London in 1922, he finished school with few formal qualifications but found a talent for draftsmanship while employed by an electrical components firm. In 1938 he enrolled in evening classes in painting at the Royal Academy of Arts. Unlike most of his classmates, Hamilton’s exposure to art had at that point been limited to magazines, cartoons, and movies. When World War II interrupted his studies, Hamilton became a technical draftsman, but returned to the Royal Academy after it reopened in 1946.

Hamilton’s problem was unprecedented: few artists had used consumer synthetics before the 1960s.

Art education had already been changing before World War II, but in the postwar period it underwent a revolution. The steady flow of American movies made teaching about marble sculptures and oil paintings appear outdated. In 1952 Hamilton became a member of the Independent Group, a convocation of like-minded critics, artists, and architects who analyzed images and films deemed too lowbrow or inappropriate by the academy. At the group’s evening meetings, science publications were discussed along with pornography magazines, architecture diagrams, and car advertisements. But in the postwar period the largest producer of such materials was an ocean away.

In 1956 two members of the Independent Group returned from a year spent in the United States with a cache of magazines, comic books, pop-music records, movie posters, and printed advertisements, none yet available in Britain. These advertisements depicted a fantastic vision: attractive, joyous housewives surrounded by bright plastic kitchen accessories, smiling families snug in the vinyl seats of speeding cars, and modern homes outfitted with the latest in radios, vacuums, and televisions.

Hamilton longed to travel to the United States; instead he made do with glossy magazines. Browsing these pages, the gap between the American dream and British reality struck him. In London everywhere he looked reminded him of the war. Hamilton’s own part of central London had sustained significant damage, and the underground was still furnished as a bomb shelter. While the American housewife was depicted smiling at the abundance and comfort surrounding her, the London Housewives’ Association had only recently celebrated the end of 14 years of food rationing.

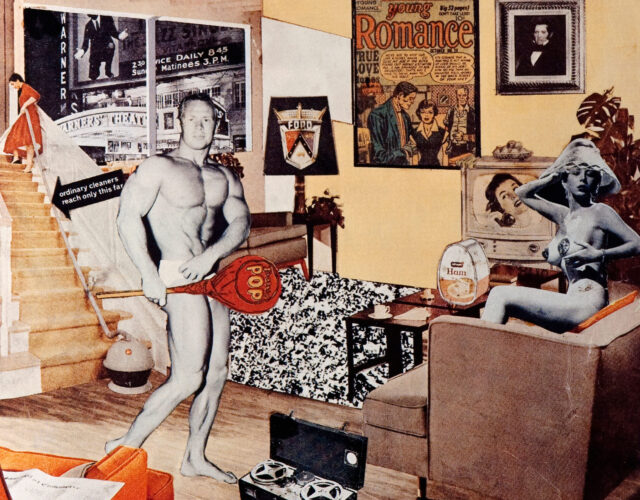

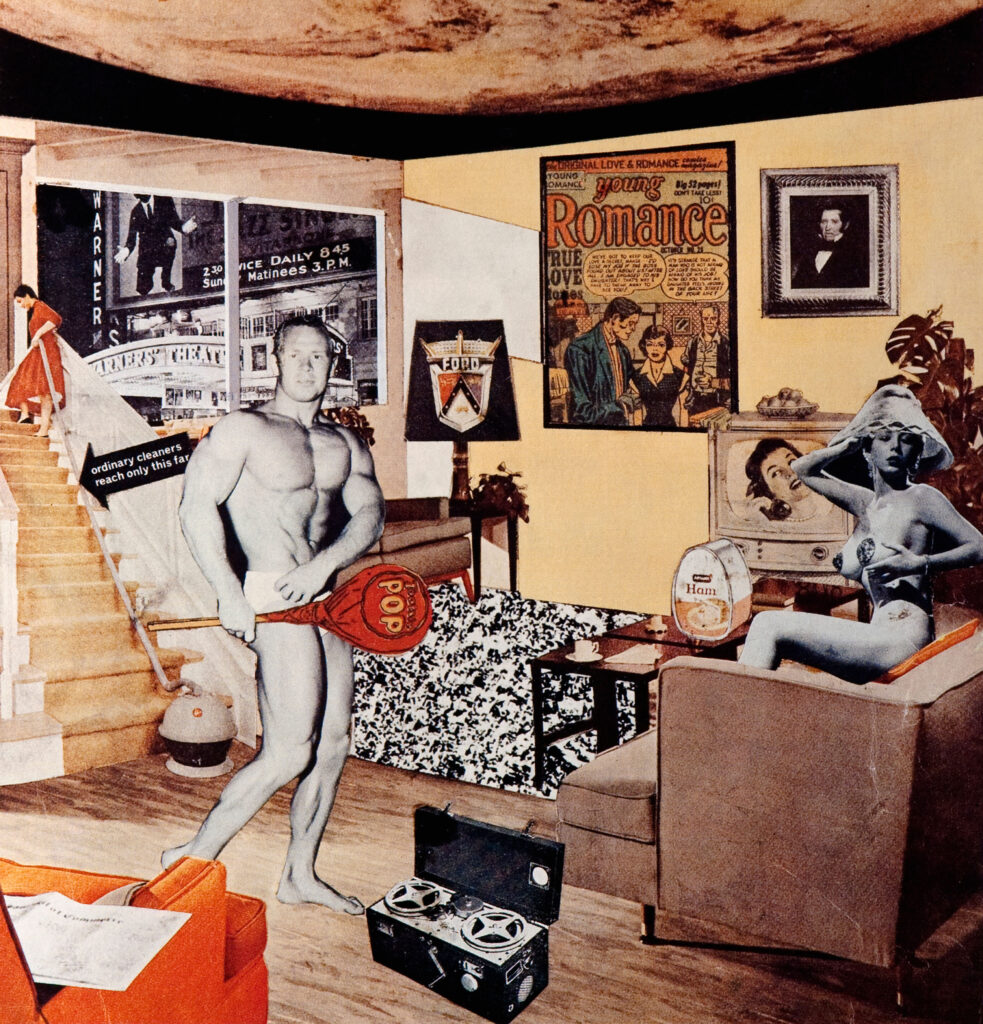

The travelers, John McHale and Magda Cordell, gave some of their loot to Hamilton, who quickly got to work. Hamilton’s 1956 Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? is a collage of advertisement elements deconstructing the American dream. The work’s title and the living room depicted in the piece are taken from a 1955 ad in the Ladies Home Journal. The image resembles a Frankenstein’s monster of modern appliances, ranging from a Stromberg-Carlson television to a Hoover vacuum. Even the room’s inhabitants belong to the public sphere of celebrity and consumption. A nude woman from an erotic magazine is positioned to sit on the couch, while a photograph of Irvin “Zabo” Koszewski, an American professional bodybuilder, appears in the foreground with a strategically placed image of a Tootsie Pop over his Speedo—a simultaneous splash of color, sexual innuendo, and a “pop” of sound.

Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (1956).

Hamilton’s living-room scene is a vast departure from Britain’s Victorian-era interiors and their emphasis on privacy. What made the American homes of the 1950s “so different, so appealing,” was that the domestic sphere had become permeable and dependent on networks of consumption and the broadcast of advertisements for products and experiences that flickered across television screens.

The collage debuted at Whitechapel Gallery’s 1956 This Is Tomorrow exhibition. Soon after, Hamilton coined the term pop art. In 1957 he proposed the following:

Popular (designed for a mass audience)

Transient (short-term solution)

Expendable (easily forgotten)

Low cost

Mass produced

Young (aimed at the youth)

Witty

Sexy

Gimmicky

Glamorous

Big business

Here Hamilton identifies aspects of pop art that would later cause him so much trouble: the embrace of the transient and expendable. Warhol engaged with the fleeting, throwaway images of popular culture by painting or screen-printing logos and motifs from magazines and billboard advertisements, translating existing consumer imagery into the realm of art. Hamilton went a step further. He created artworks out of the materials of consumerism.

Plastics play key roles in Hamilton’s pop paintings. His 1961 Pin-up is a mixed-media work exploring the female nude, a traditional subject of Western art, though here constructed as a collage of poses, costume pieces, and images drawn from such contemporary sources as Playboy. A central component of the work is a sculpted piece of plastic that evokes the exposed breasts of the pin-up model. Again Hamilton is toying with meaning through his choice of material. The shaped plastic functions as a breastplate, an accessory used by men in drag, suggesting that gender itself might be plastic—something to be realized through the performance of gender rather than biology.

In another work, $he, the nude’s identity and shape are even more fragmentary than in that of Pin-up. The consumer items that surround her, including the open refrigerator, Coca-Cola bottle, and toaster, define her. The “she” is not so much a gender pronoun as a faceless consumer. Hamilton remarked of $he, “Sex is everywhere, symbolized in the glamour of mass-produced luxury—the interplay of fleshy plastic and smooth, fleshier metal.”

Pin-up (1961) and $he (1958–1961).

Hamilton created more than an analogy between flesh and plastic in his work. As consumer identity centered on these new materials, they also became extensions of the human body. Hamilton worked on $he between 1958 and 1961, only finishing it after receiving a holographic plastic eye from a friend, the German designer Herbert Ohl. Thrilled by the gift, Hamilton attached the eye at the top of the panel, roughly where one would expect to locate the figure’s face. The plastic attachment allows $he to wink at its viewers—a flicker of movement evoking the flirtation of a movie starlet or the scheming of a used-car salesman.

In 1964 Hamilton was preparing for his solo show at the prestigious Hanover Gallery in London. This career milestone was to mark the first showing of Pin-up and $he in the artist’s native city, and the paintings’ plastic components were crucial to distinguish Hamilton’s approach from that of the New York pop-art contingent, whose notoriety was growing.

Hamilton wrote to his dealers William and Noma Copley, who owned Pin-up and $he, requesting that they send the two paintings to London. In March 1964, only four months before the show was set to open, William Copley looked at $he and Pin-up and saw that the plywood in both paintings had lifted. Pin-up displayed a prominent crack across its chest.

Hamilton was shocked to discover that his materials—so crucial to his compositions of contemporary life—had not survived two years intact. He quickly experimented with plywood, acrylic glass, and different plasticizers. With time tight, he sought the help of conservators in The Hague, where plasticizers were incorporated into the paintings to allow the materials to expand with temperature fluctuations and the passage of time without warping.

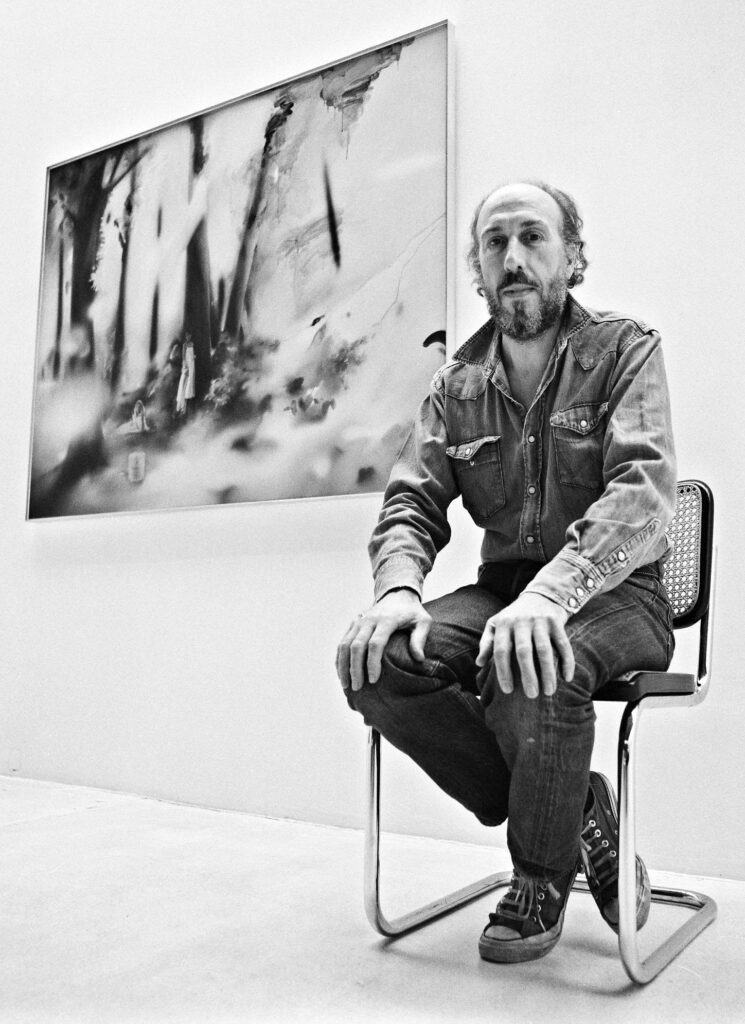

Pop artist Richard Hamilton in 1976

.

Hamilton’s problem was unprecedented: few artists had used consumer synthetics before the 1960s. Earlier plastic artworks by Naum Gabo, Antoine Pevsner, and László Moholy-Nagy relied on more durable industrial plastics, such as Plexiglas (called Perspex in the UK). In consulting with the conservators, Hamilton learned that the everyday materials he was using were becoming as complicated as the allusions he was building into his work. Each synthetic material—whether a celluloid holographic eye or a breastplate made from thermoset plastic—reacted differently to the glues and paints, as well as to temperature changes, humidity, ultraviolet light, and storage conditions.

Pin-up and $he arrived in London by way of New York, Paris, and southern Netherlands in time for the opening. The exhibition was a turning point in Hamilton’s career, resulting in critical approval and sales. Yet Hamilton’s problem with plastic wasn’t entirely solved: the crack across the breast of Pin-up reemerged due to temperature changes in the Hanover Gallery. Hamilton sanded and repainted Pin-up before sending it back to the Copleys, who were eager to exhibit the painting at an upcoming show in California. From then on, the exhibition of Hamilton’s work would go hand in hand with the conservation of plastics—a pairing ensuring that Pin-up and $he remain simultaneously historical and contemporary.

Eventually museums and conservators started to catch up to artists who use nontraditional materials, developing procedures for labeling, storing, and conserving artworks featuring plastics. In the early 1990s the Conservation Unit of the Museums and Galleries Commission of Great Britain entered a partnership with the Plastics Historical Society to encourage research into and collaboration on the long-term conservation of plastics.

When Tate conservators started a series of repairs on $he in 1989, they had a good idea of what they were doing. First, resin was thinned with a few drops of Lissapol and carefully painted into the cracks with a fine sable-hair brush. The surface was then cleaned with deionized water and covered with a sheet of silicone paper, which was weighed down with sandbags and left overnight. This procedure limited the plastic relief from rising off of the painting’s surface.

Despite the gains made in art conservation, the variety of plastics incorporated into artwork over the past 50 years makes caring for contemporary art a constant and unpredictable challenge. Today Hamilton’s early works exist both as time capsules of 1950s consumer culture and as experimental subjects for a still emerging field—the conservation of 20th-century consumer plastics.