In 1665 an outbreak of bubonic plague ravaged London. Those with the financial means to escape to the countryside did just that. Unfortunately for those left behind, the flight from the city included many of its most prominent doctors.

The London College of Physicians, which governed the licensing of doctors within a 7-mile radius of the city, had no rules demanding its members stay in residence during a plague or pandemic. They were free to run in the opposite direction of danger.

What were London’s working classes to do? They turned to the quacks, of course.

As English surgeon Dale Ingram later observed, without licensed physicians, “recourse was had to chymists, quacks . . . every one was at liberty to prescribe what nostrum he pleased, and there was scarce a street in which some antidote was not sold, under some pompous title.”

The term quack originates from quacksalver, or kwakzalver, a Dutch word for a seller of nostrums, medical cures of dubious and secretive origins. (Nostrums were the over-the-counter medications of the early modern world, available without a doctor’s prescription and taken at one’s own risk.) Quacks during this time were unregulated practitioners, many of whom were too uneducated to enter physicians’ guilds or too “low-born” to be welcomed by medical colleges. Instead they plied their trade on street corners and at country fairs, hawking homemade remedies in loud, attention-grabbing voices—hence the term quack, likening their cries to noisy ducks or geese.

Detail of De kwakzalver (The Quack), attributed to Dutch painter Jan Steen, ca. 1650–1679.

When the doctors fled London’s “Great Plague,” the quacks remained behind. Some were probably well-intentioned healers who stayed out of duty to their patients, but others recognized the lucrative business opportunity at hand. During pandemics and “plague years,” quacks are at their busiest. This was as true in 1665 as it was centuries earlier during the ravages of the Black Death, as well as centuries later, during the global influenza pandemic of 1918. In certain ways, London’s plague year might feel eerily like a prelude to our present one. It seems the quacks of the past have a few lessons to teach us.

The first is that quacks thrive in a vacuum.

Abandoned by trained doctors, London’s residents had few options besides tonic peddlers and unlicensed chemists. While the city took some measures to stem the tide of disease—including boarding up houses with known cases and keeping a careful record of deaths—they were less successful than the public-health campaigns waged in Venice, which as early as 1348 identified the need for unified civic and medical leadership during emergencies.

Venice was among the first European cities to establish a plague-fighting health office, an early form of public-health infrastructure that not only brought together physicians and city government, but also looked at the work of street sweepers, gravediggers, bloodletters, and census takers to gain a better understanding of how the plague moved—and where and how it could be stopped. It’s no coincidence our modern word quarantine originates in the Italian term quaranta giorni, or forty days, the length of time suspected plague cases (and travelers) were isolated on the Venetian island of Lazzaretto Vecchio. Mountebanks of all kinds still operated in Venice, but the development of a robust public-health defense kept the city relatively plague-free from the mid-1600s onward. (Elsewhere in Europe the plague continued to attack cities, even into the 19th century.)

The second lesson is that the most unscrupulous quacks prey on the most marginalized.

Vulnerable people—no matter what century—are particularly likely to be targeted by quacks and charlatans. English writer Daniel Defoe, better known for his colonialist fantasy Robinson Crusoe, also penned an account of the 1665 plague based on the experiences of his family members. Within it he describes the predatory way that nostrums were specifically advertised to the poor on pasted signs and noticeboards with grandiose headlines promising safety in exchange for precious coin:

In Defoe’s text the most egregious example of abuse was a quack who advertised “free advice” to the poor—without mentioning that his actual medicine would cost extra!

Defoe’s tales of the plague year may have been exaggerated, but contemporaneous medical tracts reveal that quacks weren’t the only ones who treated the poor like easy targets. In Discourse of the Plague, English physician Gideon Harvey advised his wealthier clients to avoid the poor altogether, as he believed they were more likely to carry disease and live in places that were “nastier, and more putrid than others.” Harvey’s tract listed nearly five pages of possible cures and treatments for “rich” bodies, including sweating and taking delicate foods, while his primary advice to “poor” bodies was to purge and vomit as much as possible. Considering that Harvey’s opinions were shared by many of his professional class, we can hardly fault London’s poor for turning to mountebanks for relief.

The third lesson of the quack is that when it comes to their remedies, you get what you pay for.

There was a certain amount of risk and danger involved in taking patent medicines. Ingredients were kept secret and left totally unregulated. Plague remedies sometimes included hellebore, a toxic herb thought to release sickness by producing copious sweating. Or they might include theriac, an ancient remedy that blended garlic, vinegar, onions, rue, and the flesh of a viper—thought to fight the plague’s “poison” with its own.

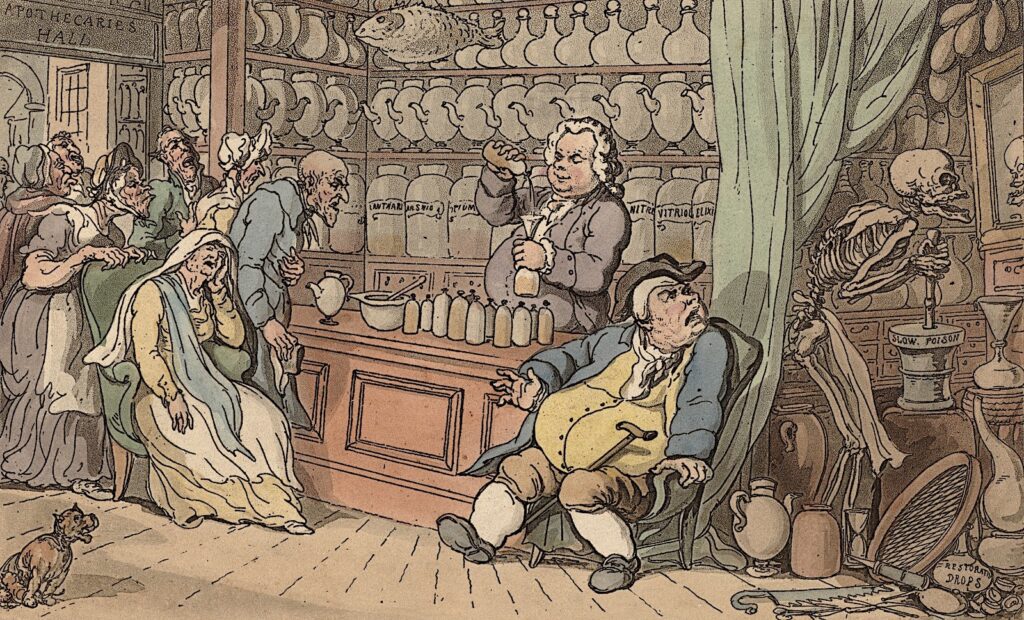

Death churns a vat of “slow poison” behind the scenes at an apothecary in this installment from English cartoonist Thomas Rowlandson’s satirical series The English Dance of Death, 1816.

Other quacks recommended smoking tobacco, lighting bonfires, or chewing wormwood and myrrh to drive away the “bad air” they believed caused sickness. As Ingram wrote in his account of the 1665 plague, “I believe it would be better for us to have no physician, than to be . . . cheated with pretended medicines.”

Of course, as Ingram was a licensed surgeon, we might take his rhetoric with a grain of salt. Even highly educated and thoroughly respected doctors made their share of errors, and their cures could be no less deadly than a quack’s. Ingram himself admitted as much when he described a “miracle” medicine sent to London by a prominent physician:

Quacks who operated during the 1918 global influenza pandemic peddled as many suspect cures as their 17th-century counterparts. The deadliness of the flu—and doctors’ inability to stem the tide of the pandemic—helped drive sales of shady cures. Advertisements circulated for Foley’s Honey and Tar Cough Remedy, Riley’s 24-Hour Flu Insurance, and Eucapine Salve, a toxic mix of eucalyptus and camphor that patients were instructed to snort and swallow to “sterilize” themselves internally.

Proprietary quinine-based remedies, such as Hill’s Cascara Bromide Quinine, were widely taken based on the understandable but mistaken belief that influenza’s and malaria’s feverish symptoms had similar origins. Even bloodletting—out of favor for almost half a century—saw a brief revival in 1918 and 1919, as desperate doctors and patients chased after miracles.

The fourth lesson is that sometimes quackery is in the eye of the beholder.

The early modern medical establishment systemically excluded women, religious minorities, and other marginalized people. As a result, many trained through personal networks of apprenticeship and worked independently by necessity. The London College of Physicians, which refused to admit or license women, brought charges against at least 100 women in the years between 1550 and 1650 for practicing “physic” without credentials.

Despite persecution and ostracism, these skilled medical outsiders often demonstrated tireless care for their communities. During outbreaks of bubonic plague in the mid-1500s, Jewish Venetian physician David de Pomis treated the sick regardless of their faith despite local laws banning Christians from seeing Jewish doctors. In 1589, after the plague receded from the city, de Pomis appealed to Pope Sixtus V for a license to continue treating the Christian patients whose lives he had saved. He also authored a stirring defense of Jewish physicians’ dedication and skill.

Attacks on Jewish physicians by Christian clergy and medical practitioners were widespread and vitriolic; many centered on lingering medieval ideas of “blood libel,” false beliefs that Jewish doctors committed ritual killings of Christian patients. In his appeal, de Pomis refuted these claims and wrote that practicing medicine was “an act of humanity,” a “sacramental bond” of duty between doctor and patient that reminds us “all human beings are equally inserted into the chain of humanity.”

In certain ways, plague itself was a strange catalyst for opening the doors of medical knowledge. Before arrival of the Black Death in the 14th century, the vast majority of medical tracts were written in Latin and only accessible to scholars; but the disease’s widespread effects led to a meteoric rise in medical texts written in vernacular languages. Many of these books were aimed not at highly trained physicians but at the plague’s frontline defenses—barber-surgeons, parish priests, herbal healers and “wisewomen,” and even small-town lawmakers—anyone who was trying to stop the plague’s local spread. (The plague had quickly ravaged Europe’s medical networks and exposed their weaknesses; in a disaster of this scale, there simply weren’t enough trained physicians to go around.) This change in medieval medical literature marked a shift away from theoretical diagnostic texts, designed mainly to educate future physicians, toward a new type of practical health advice—a how-to genre designed to be accessible to pros and quacks alike.

The fifth and final lesson of the quacks is that even the powerful and educated can be hoodwinked—or be the hoodwinker.

During London’s Great Plague, astrologer William Lilly enriched himself considerably through payments from his wealthy clients, not only for reading their fortunes in the stars but also for prescribing health tonics and determining the most auspicious days for bloodlettings.

Quacks could even reach the highest levels of patronage, as was the case for James Angier, a French quack who convinced King Charles II’s Privy Council that he could “sterilize” plague houses and prevent further infections by burning brimstone inside. So, too, for William Read, an English tailor turned itinerant mountebank eye surgeon, who Queen Anne knighted and appointed royal oculist in 1705.

In another curious incident John Wilmot, the rakish Earl of Rochester, created the character of Dr. Alexander Bendo during a brief banishment from the royal court. Lord Rochester spent several weeks in 1676 advertising the theatrical Italian quack’s medical services across London and providing consultations to would-be patients. Despite Bendo’s obvious satirical bent—his printed handbills advertised fertility cures that would prevent the “leaving of Plentifull Estates, and Possessions to be inherited by Strangers”—he succeeded in attracting a host of wealthy and prominent clients, who lined up eagerly to be fooled by a young earl in a flamboyant green cloak. In this case the quackery both began and ended at the same elite level, and it seems no amount of riches could act as a shield of reason.

It’s easy to look back and see meaningful parallels between past plagues and the current coronavirus pandemic, which has brought a new crop of aspiring mountebanks to the foreground.

Between January and August 2020, the FDA issued more than 100 warning letters to companies making dangerous false claims for products that could “cure” or “protect” against the coronavirus. These products ranged from essential oils and supplements to home diagnostic kits.

Even legitimate medicines can be tainted by quackery. The antimalarial drug chloroquine (and its variant hydroxychloroquine) was touted as a “game changer” in fighting the coronavirus in early 2020 by high-profile proponents including President Donald Trump and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro. But clinical trials later revealed the drug, which can produce dangerous side effects, had little to no effect on patient outcomes. Hydroxychloroquine hit national headlines in March when an Arizona couple, terrified of contracting the disease, poisoned themselves with aquarium cleaner they mistook for the drug. The husband died of a heart attack. Desperation, poverty, and lack of access to care drive the consumers of modern nostrums, as they have for generations.

Likewise, as in past plague years, unlicensed practitioners and community helpers have stepped in to fill the gaps of a strained global health network. In rural India, so-called quacks or village healers have been essential in establishing quarantines and sharing information about handwashing and distancing protocols in remote areas that lack health care infrastructure. In the United States, mutual aid networks, mask makers, food delivery drivers, and other nonmedical but essential workers have kept services running and helped maintain the health and safety of millions.

Though every plague or pandemic is unhappy in its own way, their histories should make us mindful of the ways in which we remain vulnerable, both to quacks and the diseases that summon them forth. Early modern physicians worked to pass laws against “unlettered chemists, shifting and outcast pettifoggers . . . stage-players, pedlars” and “prattle-prattling barbers,” but failed to ever stamp them out entirely.

Likewise, we haven’t escaped quackery, which circulates on the internet just as it circulated on London’s noticeboards. We may have medical reference texts at our fingertips, but in a world where roughly half of the planet regularly goes without basic medical care—or is frequently forced to choose between medicine and food—we can assume that some of that gap is still being filled with dubious remedies, unregulated practitioners, and wishful thinking.

The best way to fight quackery might not be pamphlets or punishments after all, but a far more potent tonic: the eradication of poverty. Without that most stubborn and entrenched of plagues, plenty of quacks would need a new line of work.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the century during which David de Pomis was active.