For religious and cultural reasons, most people in India don’t eat beef. Cows are precious and even revered assets, pulling plows and carts, giving milk, and producing dung used for fertilizer and fuel. Slaughtering cattle is taboo to Hindus, so aged animals are allowed to die naturally, with the carcasses left in open fields or taken to dump sites for vultures and other scavengers to consume.

As India’s population soared during the 20th century, its farmers’ herds of cows, goats, water buffalo, and other livestock also expanded—and so did the number of vultures, reaching as many as 40 million by the 1980s.

“They were a nuisance at the time,” recalled Munir Virani, a raptor biologist who has studied vultures in South Asia. “Thirty-five percent of all planes that were hit by birds at New Delhi airport hit vultures. The civil aviation department there hired people to shoot vultures around airports.”

“In Delhi you would park your car and just go for a weekend on the train somewhere and come back, and there were like three vultures that had built nests on the top of your car. They pooped everywhere. It was a mess,” he said.

Vultures did face some challenges in India and elsewhere around the world. They died of electrocution on power lines or were hunted. They swallowed poisonous lead bullets in carrion. Their habitats had been shrinking for decades. In Africa and Europe their numbers had noticeably decreased by the early 1980s. But while some Indian biologists voiced concern about the loss of forests where vultures nested and bred, the overall population was so massive it was inconceivable it could ever be threatened. The broad-winged scavengers were ubiquitous, and so, paradoxically, few people paid them serious attention.

So it was doubly shocking when biologist Vibhu Prakash set out in the late 1990s to update his vulture counts in Keoladeo National Park, a bird sanctuary south of Delhi, and found the birds had practically disappeared.

Back in 1985 and 1986, when Prakash was doing his doctoral research in the park, there were so many vultures it was difficult to conduct an actual count. He had seen at least 1,800 white-backed vultures then, but in 1998 and 1999 he saw only 86, representing a decline of about 96%. “The white-backed vulture has suffered large-scale adult mortality and total breeding failure,” he wrote in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. Another species, the long-billed or Indian vulture, had declined by more than 97%, from 816 to 25.

The reasons why the birds had been nearly wiped out were a complete mystery. There was no shortage of food in Keoladeo Park; old, abandoned cows wandered the grounds and died, and healthy cows sometimes perished after getting stuck in the park’s marshes, providing easy food sources for scavengers. But of 100 carcasses Prakash observed, only 8 had vultures on them.

Theoretically disease or poisoning could be the culprit, but evidence was lacking. Vultures produce highly corrosive stomach acids, allowing them to happily consume highly toxic bacteria, such as anthrax. Prakash reported that they seemed fine after eating the carcasses of cows that had been poisoned with a rodenticide. He’d heard of vultures dying in South Africa after eating strychnine-laced cow or sheep carcasses, but in the area around Keoladeo Park, “such incidents are few and far between and cannot be the cause of population crash in vultures,” he concluded. Environmental pesticides could conceivably be killing birds or disrupting reproduction, but tissue samples from dead vultures did not show significant pesticide loads.

“Intensive efforts are required to determine the cause of decline,” Prakash wrote, in the dry language of his study. “Effective conservation measures should be taken to save the species from extinction.”

Spurred by the alarming news, a team of investigators assembled by the Peregrine Fund, a nonprofit conservation organization, arrived across the border in Pakistan in 2000 to investigate the deaths. What they would discover, after years of frustrating research, is that the very reverence for cows that had allowed vultures to flourish in India had subsequently led to their near-extinction across the region. A weird confluence of cultural practices, technological advancement, and unique avian vulnerability caused a crisis that ranks among the worst human-caused wildlife die-offs in history.

Fragile Populations

While the vulture deaths were inexplicable at first, they evoked past bird population declines whose causes were well understood. The dodo had succumbed to habitat destruction and predators introduced to its native island of Mauritius in the 17th century, and its story later bolstered a new understanding that animals actually could go extinct, in apparent defiance of God’s natural order. More recently, the passenger pigeon of North America numbered in the billions until humans wiped it out through massive hunting and deforestation. The species’ numbers faded gradually at first and then more rapidly until the last one perished in a zoo in 1914.

The Indian crisis also recalled die-offs of scavenger birds elsewhere, both the Old World vultures of Europe, Asia, and Africa and the unrelated New World vultures of the Americas. Southeast Asia’s vultures were mostly gone by the 1980s, except in Cambodia. The population of California condors had plunged to just 22 in 1981 before they narrowly avoided extinction thanks to captive breeding programs.

At the same time in Europe the cinereous or Eurasian black vulture, with its massive 10-foot wingspan and markedly dark body, survived at a “fraction” of its former population, researchers reported. And in South Africa several species—the lappet-faced, white-headed, hooded, and Egyptian vultures—were in decline and mostly seen only in game reserves.

In many cases inadvertent poisoning played a major role in driving down these bird populations. The normally long-lived California condors ingested lead bullets in dead animals, shortening their lives by decades. In Africa farmers set out poisoned carcasses to kill the lions, leopards, and hyenas that hunted their cattle; vultures ate the tainted meat and died in droves, leaving the ground littered with their bodies. In Israel, Bedouin and Druze farmers are known to poison not just wolves, jackals, and wild boars but even their neighbors’ sheep, and with devastating results, said Ohad Hatzofe, an avian ecologist with the Israel Nature and Parks Authority.

“Vultures aggregate in relatively large numbers because of their biology of foraging together and nesting in colonies. So when there is a poisoning event, it’s usually many birds, not only one. That’s why they are so sensitive as a population to poisonings,” he said in an interview. “Every three or four years a population will get to the verge of extinction.”

An Ancient Relationship

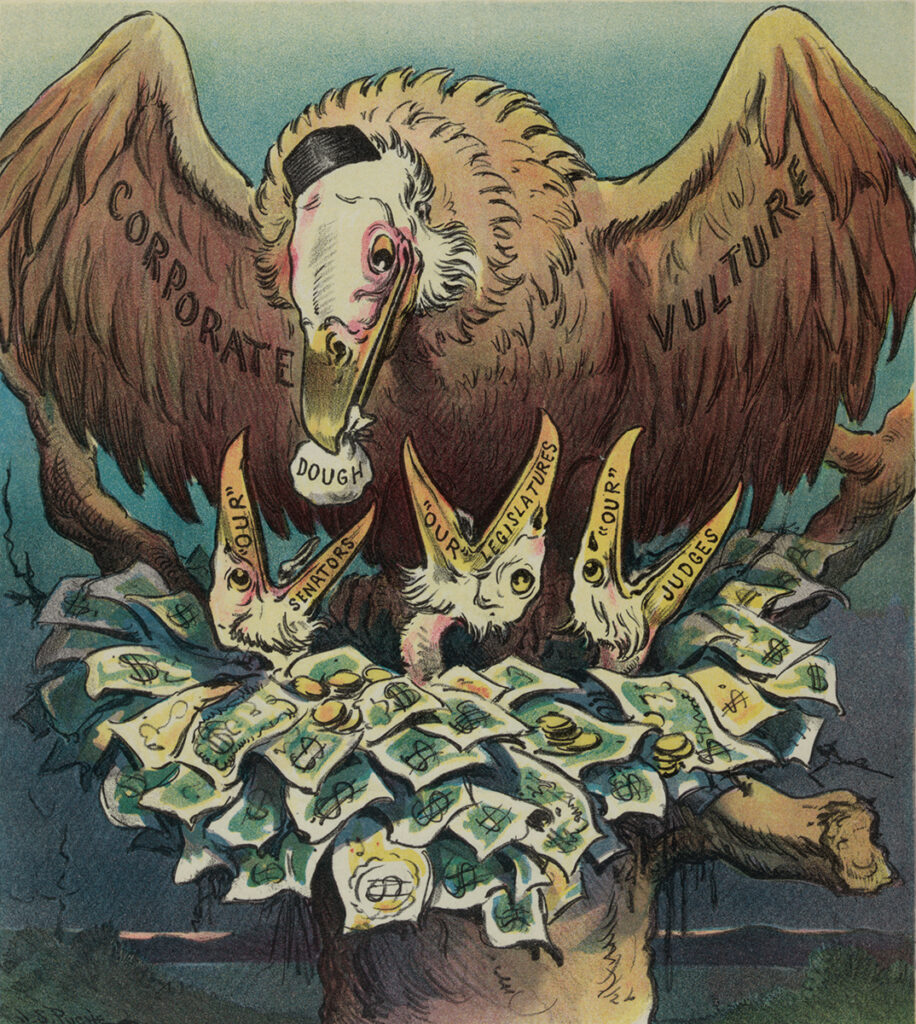

Conservationists who work to protect vultures must contend not only with a variety of environmental threats but also with a public apathy tinged with hostility and even fear. Culturally, vultures are closely associated with death, particularly imminent death, which has led to fanciful conceptions of the birds as harbingers of doom.

In movies, they are seen circling above a parched wanderer as he struggles through the desert, settling near him as he weakens. The audience understands that when he gives his final breath, the vultures will converge on him and attack, perhaps pecking out his eyes. The birds symbolize shameless, bottomless gluttony, an amoral delight in consuming the weak. In the business world “vulture capitalists” buy struggling firms and ruthlessly extract any value, driving the companies into bankruptcy. Corrupt officials are often described as vultures; Virani has a photo of graffiti in Nairobi, Kenya, where he lives, that portrays local politicians as cartoon vultures and describes them as “greedy, selfish, ineffective, insincere, arrogant,” and worse.

With their bare, featherless heads vultures can seem ugly and gross, too. Seeing a turkey buzzard on a Chilean island in 1835, Charles Darwin called the scavenger a “disgusting bird, with its bald scarlet head, formed to wallow in putridity.”

These caricatures have some basis. Vultures are experts at finding dead bodies and will scarf down any they find, including badly decomposed remains. They do, as a matter of fact, wallow in putridity, emerging from meals smeared with blood and bacteria. Some New World vultures defecate onto their own legs, apparently as a cooling mechanism. When threatened, turkey vultures disgorge acidic, stinky vomit to repel predators and lighten their load before taking off.

In general, though, people have nothing to fear from vultures. Most species aren’t interested in live prey other than small animals, such as lizards and mice. They may hang out in places where animals are likely to die, but they don’t have any supernatural power to foresee death. When circling (or “kettling”), they’re generally looking out for something that’s already dead, not waiting for an animal to perish. Many observers find their kettling inspiring. Even Darwin came to admire them.

“When the condors are wheeling in a flock round and round any spot, their flight is beautiful,” he wrote. “It is truly wonderful and beautiful to see so great a bird, hour after hour, without any apparent exertion, wheeling and gliding over mountain and river.”

The relationship between vultures and humans, sometimes mutually beneficial, sometimes antagonistic, may reach back millions of years. Vultures’ talent for spotting carcasses is used by hyenas and lions, as well as people, such as the Hadza in Tanzania: follow the flock and find your next meal. (In African game reserves the presence of vultures also alerts rangers to slaughtered elephants; to avoid detection poachers plant poisons that kill the birds.)

A group of European scientists argues that our evolutionary ancestors, the hominins, started using vultures as “eyes in the skies” in the Late Pliocene epoch, about three million years ago. They might have learned from the birds to follow migrating herds of large mammals, leading to the hominins’ dispersion out of Africa. The scientists speculate that hominins may have even seen vultures feeding on animals that had been killed in fires and been inspired to try eating cooked meat. Neolithic humans eventually returned the favor by domesticating animals, which gave vultures new scavenging opportunities.

At times our early ancestors probably competed with the birds for access to carcasses, much as hyenas and vultures in Africa tussle over fresh kills. Hominins also ate vultures, and archaeological evidence suggests that during the Paleolithic era they used the bones to make jewelry, spears, and musical instruments.

Given the scavengers’ affinity for the newly dead, early civilizations thought the birds had prophetic powers, including the ability to foretell which armies would sustain the most losses in battle (and thus provide the most carcasses). In ancient Egypt hieroglyphs depicted goddesses as vultures; in Peru dead vultures were wrapped in cloth and given formal burials, perhaps because they were thought to be ancestral spirits. They appear in Mesoamerican fables as powerful, godlike figures that can harm people or teach and help them. In the Hindu epic the Ramayana, the demigod Jatayu, who heroically battles the demon king Ravana, has the form of a vulture, as does his brother, the Icarus-like Sampati.

A group of European scientists argues that our evolutionary ancestors, the hominins, started using vultures as “eyes in the skies” in the Late Pliocene epoch, about three million years ago.

Since at least the Middle Ages vultures have been believed to have magical and healing properties, spurring markets for their body parts. Such ideas persist. In South Africa smoking dried vulture brains is thought by some to bring visions of winning lottery numbers or victorious soccer teams; after the country introduced a lottery in 2000, demand for vulture parts reportedly increased.

The flesh and bones of vultures certainly have no such powers, but the birds have been hugely beneficial to humans for the simpler reason of their attraction to rot and fondness for dead bodies. They’re a highly efficient natural sanitation system, the “garbage collectors of the savanna.” Vultures are on a constant search for carrion, speedily stripping it bare before the decaying flesh can become a breeding ground for disease. For centuries a Zoroastrian community in India called the Parsis, as well as Vajrayana Buddhists in Tibet, disposed of their dead through “sky burials,” setting them out in high places where vultures and other birds quickly turned the bodies into bare skeletons.

Other animals, such as dogs and rats, can fill the same ecological niche, but vultures are vastly preferable. From 1987 to 1997, as the vulture population cratered in India, the number of feral dogs increased from 18 million to 25.5 million, according to one estimate. It has grown to perhaps 30 million since then. An estimated 20,000 Indians die from rabies annually, mostly poor people and children; many others are injured in dog attacks. India has poured hundreds of millions into medical care and animal control. The health impact of the vulture decline, including treatment costs, loss of life, and lost income, has been estimated at $34 billion just for the period from 1993 to 2006, which does not include spending for carcass management and disposal, loss of tourism dollars, and environmental impacts.

A Surprising Discovery

By the time Vibhu Prakash’s findings became widely known, the sharp declines in vulture populations seen in India were beginning to occur in other parts of South Asia. The Peregrine Fund investigators arrived just in time to witness the devastation that hit Pakistan, where white-backed vultures were still abundant but steadily declining.

On their arrival in late 2000 the team visited a park in downtown Lahore and were fascinated to see vultures nesting in trees, unperturbed by the people below. They focused their field studies on three large nesting colonies across Punjab Province, where they observed more than 1,000 white-backed vultures breeding, feeding, raising their young, and kettling overhead, wrote microbiologist J. Lindsay Oaks, who led the investigation.

“It is difficult to describe the fantastic spectacle that occurred daily at midmorning. As the air began to warm and thermals formed, a major segment of the vulture population began to soar upward in great kettles to disperse in the search for food,” Oaks wrote. “It is also especially sad that this may have been the last significant congregation of these magnificent birds in Southern Asia.”

Down below, the researchers found the colonies strewn with vulture body parts and freshly dead birds caught in treetops. They had a hard time finding whole bird bodies to examine on the ground; in a strange turnabout fallen vultures were being consumed by feral dogs, jackals, mongooses, crows, and other birds or even being taken by people to eat. The team enlisted a professional climber, who usually worked collecting honey, to retrieve vulture corpses from treetops.

Most investigators had thought the culprit was likely an infectious disease, but it soon became clear to the research team that vultures were dying in clusters, which suggested sudden exposure to a highly lethal toxin. In one of the first birds they examined, the internal organs were covered with a chalky white paste indicating visceral gout, a result of kidney failure. People and animals develop gout when they don’t properly metabolize purines, which are nitrogen-containing compounds common in meat products, especially organs and wild game. The body turns purines into uric acid, which birds normally excrete in their characteristically white poop, the avian form of urine.

The researchers soon found many more dead vultures with gout and tested them for a long list of toxins, including heavy metals, such as lead and cadmium, and commonly used insecticides. They looked for unusual bacteria and viruses, conducting DNA studies. Yet after two years of grueling and very expensive study, they identified nothing that could be causing die-offs.

“Our frustration levels began to grow quite rapidly,” Oaks wrote. “The level of frustration and alarm grew even more when a group of ten captive vultures in our care died unexpectedly and suddenly with visceral gout, most within a week.”

The killer was in the house, and they had no idea what it was.

Virani, who together with Oaks and other colleagues helped collect 1,800 dead vultures, said the researchers stepped back and reviewed what they did know. “We had a strong suspicion these birds are getting something from their food. Their food is mainly cattle and livestock,” he recalled. “What is it that’s going into this livestock?” They surveyed local farmers and veterinarians, asking about new medicines they had recently started using. “We were looking for something that was readily available over the counter, that was inexpensive, and had the ability to cause kidney failure,” Virani recalled. “And diclofenac stood out, just like that.”

An Innovation Turned Deadly

Diclofenac is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) widely used to treat inflammation and pain, especially from rheumatoid and other types of arthritis. The investigators found diclofenac in the dead vultures with kidney failure they tested and in the buffalo meat they’d fed to the captive birds who had died. Just to be sure, they injected diclofenac into more buffalo and fed the meat to four captive birds, three of whom died of visceral gout within three days. The mystery was finally solved.

The drug had been introduced in 1973 by Ciba-Geigy, a Swiss company that later became part of Novartis. There’s an irony to diclofenac’s role in the vulture catastrophe: it had been expressly created to provide a less toxic alternative to aspirin and synthetic NSAIDs available at the time. In 1964 Alfred Sallmann and other chemists at Ciba-Geigy began studying existing NSAIDs, measuring their acidity, chemical structure, and ability to dissolve in fat, all qualities that determine how well a substance is absorbed, binds with receptors in the body, and is excreted.

They identified the ideal chemical attributes—“two aromatic rings that are twisted in relation to each other,” “a partition coefficient within the 5 to 15 range,” and so on, according to a paper by Sallmann describing the project. “More than 200 analogues, all displaying the [same] general structure . . . were synthesized and subjected to biological tests, but none of them exhibited such interesting properties as diclofenac.”

Scientists who studied diclofenac’s safety and effectiveness were aware that NSAIDs affect purine metabolism, and they knew that interfering with those biological pathways could cause overproduction of uric acid and result in dangerous gout. But in lab tests diclofenac—or Voltaren, as Ciba-Geigy dubbed the drug—seemed to have little effect on the enzymes involved in purine metabolism, and in fact it became a standard treatment for the pain and inflammation associated with gout in humans.

In 1976, at a resort on the Spanish coast, Ciba-Geigy sponsored a symposium on arthritis research that doubled as diclofenac’s coming-out party. Speakers hailed the new wonder drug, which appeared to be more effective and produced fewer side effects than other NSAIDs such as naproxen, the active ingredient in Aleve and other painkillers. In closing remarks at the symposium’s end a doctor named R. Oberholzer compared diclofenac to a baby that gestated for 10 years before being born and raised by the scientists, its “proud parents.” The drug had matured and finally started school, he explained. “Voltaren seems to have drawn level with the best child in its class and . . . shows every sign of developing into a very well-behaved youngster,” Oberholzer told the conferees. “I only hope that it continues to behave itself!”

The health impact of the vulture decline, including treatment costs, loss of life, and lost income, has been estimated at $34 billion just for the period from 1993 to 2006.

As it happens, Ciba-Geigy products have a history of affecting bird populations. Paul Hermann Müller, a chemist at Ciba-Geigy’s predecessor firm J. R. Geigy, had in 1939 discovered the insecticidal properties of DDT. That discovery, which won Müller a Nobel Prize, led to worldwide use of the chemical, which was later implicated in the decline of condors, bald eagles, peregrine falcons, and several other species, and was the chief villain of the landmark environmental book Silent Spring.

Oberholzer must have been delighted: diclofenac grew big and strong and established footholds around the globe. Under different names and varying formulations, as pills, patches, lotions, and liquids, it became the most widely prescribed NSAID in the world. A 2011 analysis of NSAID use in 15 countries found that its market share was nearly that of the next three most popular drugs combined. In the United States 10 million prescriptions were filled in 2012.

For decades diclofenac was used primarily for arthritis in humans, but around 1994 in India and 1998 in Pakistan, veterinarians began using it to treat sick domestic water buffalo and cattle, usually by injection. It was cheap and effective; its patent had expired, and it was manufactured by more than 50 companies in India. Diclofenac allowed rural families to ease their domestic animals’ aches and pains so they could continue working.

“People were seeing visible results,” Virani said. “You know, in Hindu culture, the cow is the mother, because it provides milk. And cows are valuable: they plow the fields, they take the produce to market, they provide milk, they do everything. People use intensive veterinary management. And it’s so cheap to get any drug over the counter.”

When a cow is given diclofenac, the drug breaks down quickly and becomes undetectable in the body after about three days. Yet a remarkable confluence of factors still allowed the medicine to devastate vultures. For one thing, while some anti-inflammatory medicines have little effect on the birds, they are exquisitely sensitive to diclofenac. Like other NSAIDs, such as aspirin, the drug suppresses production of compounds called prostaglandins, which reduces inflammation but can also have a number of other effects, including restricting blood flow in the kidneys. The malfunctioning organs stop removing uric acid from the blood, leading to rapid gout and death. The lethal dose of diclofenac in vultures is about one-tenth of the therapeutic dose for mammals by weight.

In addition, it only takes the occasional tainted buffalo carcass to cause an outsized effect on the local vulture population. The scavengers soar high and spot every single large, dead animal over vast distances; dozens of birds may descend on a body, strip it clean in an hour, and die within days. If this happens enough times, deaths in a vulture colony soon outpace births. Most vultures don’t breed until they’re four or five years old, and the females lay only one egg a year, which may or may not hatch. Young birds face a number of threats in addition to poisoning, and as many as half do not survive to adulthood. Mathematical modeling suggests that as few as 1 in 760 contaminated carcasses could drive down the vulture population 30% per year.

Taking Action

Armed with the evidence that diclofenac had ravaged South Asian vulture populations, the Peregrine Fund and other groups convened summits in Nepal and India to prepare recovery plans. Conservation organizations educated government agencies, leading to bans on manufacturing of veterinary diclofenac in India, Nepal, and Pakistan in 2006. To encourage vets not to simply turn to other potentially dangerous NSAIDs, such as flunixin or ibuprofen, researchers identified a safe alternative, meloxicam, which they successfully tested in vultures.

At first the birds’ numbers continued to fall year after year. India did not ban actual sales of veterinary diclofenac until 2008, and even then the country still allowed human diclofenac products, which could be easily diverted for use in livestock. Large vials of diclofenac remained available in pharmacies for several more years. While vets did begin to prescribe meloxicam, its higher cost and perceived lesser effectiveness slowed adoption. Other veterinary NSAIDs that kill vultures, such as ketoprofen, remain available in most of South Asia to this day.

Finally, around 2011, the population of white-backed vultures stabilized, according to a study coauthored by Vibhu Prakash, the biologist who first documented the birds’ decline in Keoladeo Park two decades earlier. Their numbers may even be increasing slightly.

“It’s a great success story, but it’s not one where you can open a bottle of champagne yet,” said Virani, who is now vice president and global director of conservation strategy of the Peregrine Fund. “We continue to remain cautious and prudent about this thing. But what we can say is that the crash is over.”

Of the nine species of vulture that live in or regularly visit India during migration, four are classified as critically endangered across their ranges: the white-backed, the Indian or long-billed, the red-headed, and the slender-billed vultures. The Egyptian vulture is endangered, and the Himalayan, cinereous, and bearded vultures may be threatened in the near future, while the Eurasian griffon, which is concentrated outside of South Asia, is globally stable. In the early 1990s at least 40 million vultures, and possibly many more, lived in India; by 2015 the combined number of Indian, white-backed, and slender-billed species had dwindled to perhaps 19,000 in the whole country.

Under different names and varying formulations, as pills, patches, lotions, and liquids, diclofenac became the most widely prescribed NSAID in the world.

To boost the vultures’ chances of survival, a captive breeding program was established, and India now has five such centers holding more than 600 birds. The process is expensive, labor intensive, and excruciatingly slow. Success is not guaranteed—the vultures could still go extinct—although breeding programs in California and Europe have been able to buoy threatened populations. A center in Nepal released eight captive-bred vultures in September 2018, the first such effort in South Asia. The Indian centers are hoping to release their first captive-bred birds soon.

Diclofenac bans are strictly enforced around the breeding centers and in safe zones that have been established in several locations across the region. In Nepal six “Jatayu restaurants” offer diclofenac-free meals for the vultures. These programs buy old cattle or receive donated animals, allow them to die naturally, skin them for the leather, and leave the carcasses out for vultures to safely consume. While it is difficult to ensure the meat is completely free of toxins, similar centers operate in India, Pakistan, and Cambodia.

The Long Battle Ahead

India is not the only country where conservationists are laboring to protect minuscule bird populations. Israel, which 100 years ago had several thousand vultures, now has about 180 resident Eurasian griffons along with 100 Egyptian vultures that migrate there in the summer, according to Hatzofe, the avian ecologist who oversees the country’s vulture protection programs. A few lappet-faced, black, and bearded vultures can also be spotted on rare occasions.

Israel’s wildlife agency now breeds and releases vultures, imports rehabilitated birds from Spain, tracks their whereabouts with GPS, stocks 30 feeding sites with drug-free carcasses, and protects individual nests that have eggs or chicks. On top of these efforts the agency works to prevent aircraft collisions, researches emerging threats, supports public-education programs, tries to prevent wind-turbine projects, and operates a de facto predator management program, Hatzofe said.

Staff members use helicopters to spot dead cows and have four trucks that clear 300 tons of dead animals a year—including sheep, camels, and cattle—to stem the overabundance of jackals, feral dogs, foxes, and wild boars that feed on them. The government collects the carcasses and works with Druze and Bedouin shepherds to discourage them from setting out poisons to protect their herds. Every cluster of inadvertent vulture poisonings is a serious blow in a country that has so few of these birds; without captive breeding and release Israel’s vulture population would certainly decline further, Hatzofe said.

“There is no other place on Earth that is doing all these things that we’re doing, from academic research to actual management in the field, and all the time adapting and changing,” he said. “It’s a lot.”

Adaptation is key. With such a fragile population and diverse array of threats, there is no guarantee numbers will steadily increase. Historically, they have fluctuated dramatically. Israel had at least 1,000 pairs of Eurasian griffons in the early 20th century, which declined to 80 pairs in the early 1980s owing to food shortages, poisoning, electrocution on power lines, nest disturbances, and poaching, according to the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel. By the 1990s, thanks to conservation programs, the population recovered to 150 breeding pairs, or as many as 900 individual birds, but poisonings and swallowing of lead bullets drove the number down again.

Mathematical modeling suggests that as few as 1 in 760 contaminated carcasses could drive down the vulture population 30% per year.

Prospects for vultures are also dire in Africa. A 2015 survey of 95 vulture populations in 22 African countries found that 89% of the populations had suffered major declines or disappeared entirely over the previous few decades. Sixty-one percent of recorded deaths were due to poisoning, 29% to capture for trade in traditional medicine, 9% to electrocution or collision with electrical infrastructure, and 1% to killing for food. Many countries lack robust programs to combat these problems, some of which are worsening. Trade in vulture parts appears to be expanding, and an American aid program is bringing electrical lines to more of sub-Saharan Africa.

In India “we had to deal with just one problem, which was caused by accident, and we nailed it,” Virani said. “Something could be done about it. But in Africa, it’s such a challenge because of the different countries involved and the different cultures, and the different threats to the vultures as well.”

Much of Virani’s work focuses on Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve, home to all the best-known African animals. Vultures get much less attention than the big predators and wild game, but they are all threatened by poisons farmers set out in response to attacks on livestock. Virani’s organization trains game scouts and others to respond immediately to reports of poisoned carcasses before too many vultures and other animals die.

When a poisoning is reported, trained conservationists, some of them Maasai themselves, go talk to the aggrieved farmer. They drink “oceans of tea” as the farmer complains about the dead cows, Virani said. Then they discuss options. In one area conservationists can help cattle owners put flashing lights around their properties, which is very effective at driving off lions and other predators. A group called the Big Life Foundation has a fund to compensate farmers. Often neighbors will contribute to help offset a farmer’s losses.

“If he’s lost a small number of livestock, then people within the community and around the village will help,” Virani said. “One guy will give a cow, another guy will give a goat, someone else will give a small sheep. So he’s sort of consolidated. He’s like, all right, I’m happy with it.”

Stopping poisoning completely is impossible, but Virani believes it can be made so infrequent that vulture populations can grow again. “It’s going to take time. It’s going to take effort. It’s not easy,” Virani said. The tentative signs of recovery in India and other places show that societies can change in ways that allow the birds the possibility of a viable future.

“I am an optimist,” he said. “I know we can fix this.”