In 2019 community organizer Abdul-Aliy Muhammad learned that the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology had a collection of more than 1,000 human skulls—skulls taken from people without their consent and amassed to “prove” white supremacy. With the help of a PhD student, Abdul-Aliy went on a crusade to change the way museums claim ownership of human remains, forcing them to acknowledge that all people deserve a final resting place. Along the way, they realized the problem was much bigger than just the skulls or the Penn Museum. They realized that claiming ownership over the bodies of marginalized people is not just a relic of the past; it continues to this day.

About Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race

“Return, Rebury, Repatriate” is Episode 5, Part 1 of Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race, a podcast and magazine project that explores the historical roots and persistent legacies of racism in American science and medicine. Published through Distillations, the Science History Institute’s highly acclaimed digital content platform, the project examines the scientific origins of support for racist theories, practices, and policies. Innate is made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom.

Credits

Host: Alexis Pedrick

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Padmini Raghunath

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

“Innate Theme” composed by Jonathan Pfeffer. Additional music by Blue Dot Sessions.

Resource List

It’s past time for Penn Museum to repatriate the Morton skull collection, by Abdul-Aliy Muhammad

Penn Museum seeks to rebury stolen skulls of Black Philadelphians and ignites pushback, by Abdul-Aliy Muhammad

Penn Museum owes reparations for previously holding remains of a MOVE bombing victim, by Abdul-Aliy Muhammad

City of Philadelphia should thoroughly investigate the MOVE remains’ broken chain of custody, by Abdul-Aliy Muhammad

Black Philadelphians in the Samuel George Morton Cranial Collection, by Paul Wolff Mitchell

Some skulls in a Penn Museum collection may be the remains of enslaved people taken from a nearby burial ground, by Stephan Salisbury

Remains of children killed in MOVE bombing sat in a box at Penn Museum for decades, by Maya Kassutto

The fault in his seeds: Lost notes to the case of bias in Samuel George Morton’s cranial race science, by Paul Wolff Mitchell

She Was Killed by the Police. Why Were Her Bones in a Museum?, by Bronwen Dickey

Corpse Selling and Stealing were Once Integral to Medical Training, by Christopher D.E. Willoughby

Medicine, Racism, and the Legacies of the Morton Skull Collection, by Christopher D.E. Willoughby

Final Report of the Independent Investigation into the City of Philadelphia’s Possession of Human Remains of Victims of the 1985 Bombing of the MOVE Organization, prepared by Dechert LLP and Montgomery, McCracken, Walker & Rhoads LLP, for the city of Philadelphia

The Odyssey of the MOVE remains, prepared by the Tucker Law Group for the University of Pennsylvania

Move: Confrontation in Philadelphia, film by Jane Mancini and Karen Pomer

Let the Fire Burn, film by Jason Osder

Philadelphia Special Investigation Commission (MOVE) Records, archival collection at Temple University’s Urban Archives

Transcript

Alexis Pedrick: Welcome to our new season Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race. This is episode five: “Return, Rebury, Repatriate.” Before we start, a content warning for our listeners: this episode covers topics, stories, and historical details about violence and the mishandling of human remains.

Alexis Pedrick: In 2019, Abdul-Aliy Muhammad learned that a group of students at the University of Pennsylvania was researching whether the school had any historic ties to slavery.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: I’m not a Penn student, didn’t go to Penn. I am from the neighborhood that Penn is in, I’m from West Philadelphia, born there and raised there and have a very complicated relationship with the university because of that.

Alexis Pedrick: Penn is an Ivy League university, situated right on the edge of West Philadelphia, a predominantly black section of the city, just across the Schuylkill River from downtown. The neighborhood was originally designed as a streetcar suburb. Trolleys still rolled through it, past huge trees and big Victorian houses, as well as smaller row homes like what you see in the rest of the city. Now, Penn has been systematically gentrifying West Philadelphia for decades now, so there’s a lot of tension between the school and the people who live in its shadow, like Abdul-Aliy.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: As a black person, you kind of think about old institutions and what they may have done to either participate in, or benefit from, the subjugation of black folks.

Alexis Pedrick: Abdul-Aliy, who identifies as non-binary, is a community organizer, poet, and journalist. For the past few years, they’ve been at the center of a controversy about the ethics of keeping human remains at the Penn Museum of Archeology and Anthropology. It all started in April, 2019 when they saw an ad on Facebook for a symposium about Penn’s complicity in the transatlantic slave trade.

Abdul Aliy Muhammad: Like, I don’t know how I exactly how I came upon the ad, but it was obvious that it wasn’t meant for me, you know, that it wasn’t intended for me to participate.

Alexis Pedrick: The symposium was technically open to the public, but Abdul-Aliy was the only person there who wasn’t academic, or sort of academic adjacent. There were scholars from Penn and other universities. In fact, the list of presenters reads like a who’s who of this podcast season. There were also presentations from undergrad and grad students. One of the highlights was a presentation of new research done by a PhD student in the anthropology department.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: So, my name is Paul Wolff Mitchell. My research focuses on the history of anthropology, of anatomy of human remains, particularly in the museum context, and the history of race and scientific racism.

Alexis Pedrick: At that symposium, Paul Wolff Mitchell shared research about the Morton Cranial Collection, skulls collected by Samuel Morton, a 19th century physician who taught at Penn’s Medical School in the 1830s and 40s. He was also a naturalist and is now recognized as the founder of American Physical Anthropology. He helped lay the foundation for Penn’s anthropology Department and the Penn Museum of Archeology and Anthropology. During his presentation, Paul spoke specifically about how some of the Morton skulls had belonged to people who were enslaved. He remembers how this information hit Abdul-Aliy Muhammad, who he saw in the audience,

Paul Wolfff Mitchell: Abdul-Aliy Muhammad was present and had learned for then at the first time, that there were the remains of enslaved people that were at that point, on display in a classroom at the Penn Museum, and that Morton had actively collected the remains of enslaved people and that Morton had promulgated these white supremacist, scientific racist ideas.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: So when I learned that, that was, I think, the most shocking part of the history I learned, it was all very, like troubling and problematic. But I think the knowledge that the crania of enslaved people were physically on display and that students could interact with the crania, could, you know, be in the space with them, and that you could visibly see the crania from a window if you were like walking by. So learning that made me want to act.

Alexis Pedrick: The skulls were being treated like scientific objects, relics from a distant past. But for Abdul-Aliy, they were captive ancestors who had never consented to being there. Sitting in the audience at this academic event, Abdul-Aliy felt like they were having a different reaction to the skulls than everyone else.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: Cause I was angry. You shouldn’t be angry in an academic space. You should be level-headed. You know, calm and uh, kind of understand that this is how things are done. And I had none of those reactions. I had the opposite reaction, which is like, why? What are you doing about it? Who’s organizing around this? Nobody’s organizing around this. It didn’t seem like people felt that they should take action, and so I didn’t understand this kind of separation between like knowledge and action , you know, but it was mostly kind of like, ‘oh no, yeah, this is disturbing. I don’t know why they’re on display. You know, this is, this is kind of how it’s done. This is how it’s always been done.’

Alexis Pedrick: Abdul-Aliy decided then that they would do two things, start a petition and pitch an article to the Philadelphia Inquirer, both calling on Penn to return the skulls, and Paul went back to working on his PhD.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: And how I saw my role with regard to their remains was to make this information available, but to make it available such that the information was in the light. That’s all.

Alexis Pedrick: Abdul-Aliy and Paul were about to embark on similar journeys, exposing the violent stories behind these skulls, and it would create an unlikely partnership of sorts, the Ivory Tower academic and the West Philly activist. The insider and the outsider.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: You know, here’s nerdy me, dusty in an archive. Here’s Abdul-Aliy, you know, fighting the fight in the newspapers.

Alexis Pedrick: Both Paul and Abdul-Aliy were about to start asking a lot of questions that would expose fault lines museums have only recently begun grappling with on a large scale.

Subhadra Das: We all know, right, that the whole purpose of a museum is that it’s somewhere that’s really handy to go if it’s raining or you need the bathroom. And also, you know, if your kids are, like on school holidays and you need somewhere to take them. That’s the main function of museums in our society today. But back in the day, museums performed a very, very different function.

Alexis Pedrick: This is Subhadra Das. She’s a historian, researcher, and storyteller who looks at the relationship between science and society.

Subhadra Das: The little trilogy that I like to talk about is that science was a tool of empire. Museums were a tool of empire. Therefore, it stands to reason that science museums are a tool of empire.

Alexis Pedrick: Even though they weren’t using this word, what Abdul-Aliy was calling for when they talked about returning the skulls was something called decolonization.

Subhadra Das: Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization is a process. And the part of that, that really feeds into museums in my interpretation, is this process of acknowledgement. So, telling the whole story, acknowledging what has happened, acknowledging the context of things and where ideas come from. In ways that perpetuate social injustice. But then there’s also a doing aspect of this as well, which is to do with repatriation. The people need to go back to their families. The things, however we conceive of as things, need to go back to where they came from. So to me, to decolonize the museum is we deconstruct both of those things at the same time.

Alexis Pedrick: Today there are efforts to decolonize museums around the world. Now, this episode is about how the process has played out at one museum when a group of people demanded the repatriation of the Morton Skull Collection and how in the process of doing so, they discovered that claiming ownership over bodies of marginalized people is not just a relic of the past.It continues to this day.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter One. Strategic Depersonalization.

Alexis Pedrick: Before we go any further, let’s deal with a couple of essential questions. Where did Morton get all of these skulls and what was he doing with them? To answer the first question, we have to go back to the 19th century. Let me set the scene a little bit. It’s the anatomical era of American medicine. Medical practice was growing, professionalizing, and physicians were dealing with corpses all the time, and many felt entitled to do what they wanted with them.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: They presumed a certain power and a right over the bodies of the dead. ‘We need to have bodies to train surgeons, to train physicians. And insofar as that’s true, then somebody’s body has to be on the slab.’ ‘And there are some people,’ Morton says this explicitly, ‘some people are nothing but a burden on society during their lives. And society has, in Morton’s words, a just an imperative claim on their bodies after death.’

Alexis Pedrick: In other words, physicians like Morton thought some people didn’t count, and their bodies were fair game. Whether it was to teach medical students how to do surgery, to advance basic research, or simply to satisfy a physician’s curiosity. Technically speaking, the only legal cadavers came from executed criminals, but those alone couldn’t satisfy the demands of all of Philadelphia’s medical students and doctors. So they illegally procured other bodies, as in, they stole them or, well, paid other people to steal them. Mostly from almshouses and potter’s fields.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: Medical schools in the city actually created secret agreements about the distribution of cadavers. Why secret? So that, um, it didn’t upset, uh, public sentiment. Grave robbing occurs at night. It’s not done during the day.

Alexis Pedrick: A key element was what Paul calls strategic depersonalization: intentionally concealing the identities of some victims.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: He’ll give people who were, again, presumed to be criminal, but other ones were intentionally withheld. These anatomists were often in a very calculated way, withholding information about the remains that they had, so that identification by kin was not possible, or so that the violence inherent in the processes of building these collections was not clear.

Alexis Pedrick: Almshouses were hospitals for people without means. They were described by physicians who worked there as abysmal places, both to live and to die. Patients there wrote petitions to the governing body, begging not to be buried in the potter’s fields because so much grave robbing and body snatching was going on. But the city’s elite pretty much turned a blind eye, as long as the cadavers didn’t look too much like themselves. And this included anyone who was poor, “deviant,” immigrant, or black.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: In effect the access to bodies, particularly of the poor, was what made the University of Pennsylvania so prominent a place in medical education because anatomy was so central to medical education in this period.

Alexis Pedrick: Medical students at Penn trained at the Blockley Almshouse. The patients, or inmates, as they were tellingly called, were reduced to teaching tools. While they were alive, students practiced treating them bedside, and when they died, they became anatomical specimens for dissection and practicing surgery. They also wound up in Morton’s skull collection. In fact, the very first skull listed in his catalog is of a black man who was likely one of his own patients at the Alms house. But Morton didn’t stop there. He got skulls from around the world often using connections he had as a member of the prestigious Academy of Natural Sciences.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: The people that he’s asking are in the U.S. Navy or in the U.S. military. They are traders, they are diplomats, they are other scientists. They are enslavers.

Alexis Pedrick: And this brings us to our second question—what was Morton doing with these skulls? He was using them to prove that the racial hierarchy that already existed in the world in a social and political way was actually natural and innate. And the social and political hierarchy that put him as a white man at the top was what allowed him to get the skulls to furnish his proof. Historian of race science, Chris Willoughby, describes it as a disturbing feedback loop.

Christopher Willoughby: Human remains are the source material for creating a global racial system of white supremacy, and those are only obtained through imperial violence and networks of commerce. In the case of Samuel Morton, he has an agent in Egypt, who collects more than a hundred crania, who’s the vice console for the United States. So imperialism and these networks of aggression are what supply human remains, and then those human remains are studied to justify those same systems.

Alexis Pedrick: Systems based on race, which all kinds of people contributed to defining from philosophers like Emmanuel Kant to botanists like Carl Linnaeus. But Samuel Morton came along when race science was getting increasingly medical. See, a philosopher can look at a person and speculate about their external features. Defining race by skin color or hair texture. But you need specialized training to say something about the inside of someone’s body.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: It’s the instability of skin color and anxieties about how it might change or could change that is a motivator for trying to find race deeper inside the body.

Alexis Pedrick: Fair-skinned Europeans were anxious that if they went to warmer tropical climates, they might become darker and they were even more anxious that this might pass on to their descendants.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: There was also concern about the inverse happening, which is that dark-skinned people coming to Europe and then becoming white.

Alexis Pedrick: You see what’s happening here, right? The whole system has been built on external markers, but when that proof starts falling apart, race scientists move the target.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: And in the middle of the 18th century, there’s a move to say, ‘well, okay, so the external environment does all of these things, yes, yes. But what happens when we look at the bones, which are inside and are not accessible to all of these factors that can change?’ And some of those are the features of the skull. And what makes the skull so crucial is indeed the way in which it is thought more than any other part of the body to reflect the mind.

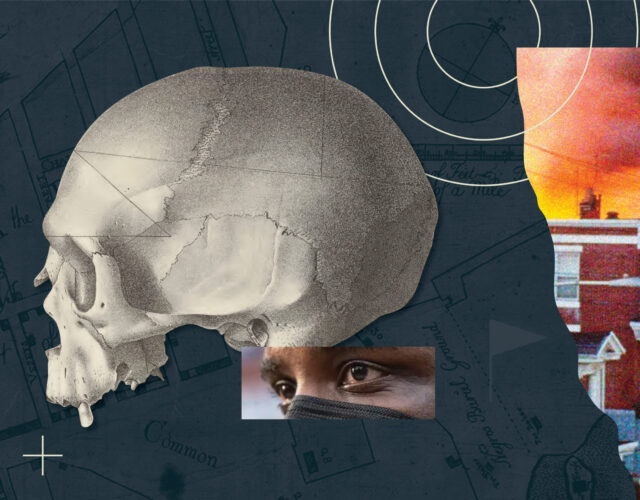

Alexis Pedrick: So, skulls in hand, Morton employed his “scientific method.” First, he filled them with white peppercorns, though later used lead shot. Then he measured that volume in cubic inches and took the average of each racial group, and then built a hierarchy of five races based on those numbers. And when Morton grouped his skulls in order from largest capacity to smallest, he had Caucasian skulls at the top with the most mental capacity, followed by Mongolian, Malay, American, and Ethiopian at the bottom. Now, there’s been a lot of debate over the years about these numbers. Are the measurements accurate? Was the math right? But these questions are kind of missing the forest for the trees. There are so many reasons that Morton’s conclusions were incorrect. His bias, the fact that he actually believed the races he grouped were all completely different species, but we also now know that the brain is a complex organ, and your intelligence is not based on its physical size. And that might seem like a good stopping point, right? Morton was racist. The skulls don’t prove intelligence. It’s now been over 180 years since his conclusions. And in that time, the world has changed. The Emancipation Proclamation happened. We got a Black president, even a Black vice president. But the skulls and the problems with them didn’t just disappear. There they were in 2019, in a classroom at the University of Pennsylvania,

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Two. Black Ancestors Matter.

Alexis Pedrick: There are about 1300 skulls in the Morton Cranial Collection. Many of them are labeled directly on their foreheads like this one, skull number 960: “Negro born in Africa.” And there are others labeled “idiot” and “lunatic.”

VanJessica Gladney: And I don’t know, like I’ve never taken an anthro class, but I do know that there’s just something really frustrating about a Black student in an anthropology class, sitting there and literally sitting in the shadow of something that was used to prove that that student should not be there.

Alexis Pedrick: In 2016, VanJessica Gladney was an undergraduate at Penn. At the time there was a sort of movement where elite universities were confronting their ties to slavery, and Penn had made a statement saying they had none.

VanJessica Gladney: This is around the time when Brown and Georgetown and all these schools are saying, ‘oh, you know, here’s where our connections lie,’ and such and such, and Penn came forward and said that we are on the right side of history. Now, I was actually a sophomore or a junior when this information came forward. And I remember saying something to a professor because we were having a conversation about Princeton, and they were changing building names. And I said, ‘oh, well thank God. Like, you know, Penn doesn’t have anything to think about in that regard.’ And she said, ‘All right, time out, no, no, no.’

Alexis Pedrick: That professor invited VanJessica to join an independent study that would investigate whether or not Penn’s statement was really true. The group became the Penn and Slavery Project. This was the same group that put on that symposium in 2019 where Paul Wolf Mitchell presented an Abdul-Aliy Muhammad first learned about the Morton Skulls. VanJessica was there too, on a panel presenting the students’ findings. One of the first things the group decided was that just because the university never outright owned slaves, that didn’t exonerate them,

VanJessica Gladney: We kind of all agreed that, well that’s, that’s not really how it works. You can’t just say that. ‘Oh, the university didn’t own anybody, so we’re not complicit.’ Sure. The institution may not have owned enslaved people, but we definitely profited from the institution of slavery, benefitted from the institution of slavery, and in some ways helped continue to support the institution of slavery.

Alexis Pedrick: With this broad scope in mind, it was clear that the Morton skulls were an obvious part of the problem.

VanJessica Gladney: What’s really frustrating is that the Morton collection created and supported this idea of racial difference. But then the handling of it speaks to the fact that we do believe there is a racial difference. There isn’t, but there is. I mean, difference only exists because you believe it exists. And if we are treating the remains of a group of people whose bodies were used to invent this idea of difference between the races, and we are okay with saying, oh, well it’s fine that they’re in closet. And it just makes me realize how much work we have to do.

Alexis Pedrick: One of the talks of the symposium focused on a subgroup of the Morton Collection, the skulls of 55 Africans who had been enslaved in Cuba. Penn professors and students had been using these skulls for research as recently as 2020.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: So many people who I talked to are not academics, not tied to institutions. But are just, you know, regular folk are like, ‘why, why for so long? Why has this happened? How is this okay?’ And, and then to be met with the academic response, which is, ‘uh, we need, you know, these remains to do research, you know, we have to digitize it. Look at the bones to see, you know, how enslaved people their nutrition was.’ You know, that’s some of the responses I’ve heard from people and that’s not okay. You don’t get to prod and process and research people who’ve been harmed in their lifetimes and in their afterlives. You don’t get to decide to do that for the sake of science.

Alexis Pedrick: A cultural anthropology professor at Penn named Deborah Thomas was also at the symposium. By the way, she and her husband were the first Black faculty in the department when they came in 2000. When she saw Abdul-Aliy’s reaction, it confirmed something she already knew: that someone could spend their entire life in West Philadelphia, with Penn in their backyard, and still not really know what’s going on inside.

Deborah Thomas: I mean, if people don’t know those histories, if they don’t know the histories of ethnographic museums, if they don’t know the histories of the discipline and particularly of physical anthropology, you wouldn’t be able to conceive of, you know, ancestors living in museums to the degree that they do. But if you are in that history and, and work in that discipline, of course you know that this is completely common that ancestors live here. Maybe 10,000 individuals or pieces of individuals are still in the Penn Museum.

VanJessica Gladney: I think once we had people from outside of the Penn Museum and inside of the Penn community and then outside of the Penn community altogether, that’s when things really got rolling. I think it awakened a lot of students into realizing that academia can function as activism.

Alexis Pedrick: Abdul-Aliy Muhammad brought their non-academic worldview into what was usually a closed academic space, and they said, this is not okay. We need to do something. And then they shared that opinion with the rest of the regular folks in Philly through our newspaper, the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: They demanded that these remains be reburied that they’d be given to the descendent community for, reburial and that this was a part of a broader conversation of reparations.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: And it was during the time that Democratic presidential candidates were talking about reparations and, and I felt deeply and still deeply feel that Penn owes reparations.

Alexis Pedrick: Penn didn’t respond for more than a year, until the summer of 2020 when George Floyd was murdered by police and mass demonstrations swept the world. Penn finally responded with three steps they were going to take. One, stop doing research on the remains of enslaved people. Two, take the skulls off display, and three, finally work towards repatriating them.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: It’s a strange feeling. That someone had to have their neck compressed and die, and for people to organize in the streets, for institutions to look into the possibility of repatriation. I feel like that is a testament to how deeply ingrained whiteness and racism is in our society, because in 2019 this was as important as it was in 2020, as it is in 2022. You know, it shouldn’t have to be tragedy, state sanctioned violence, and public outcry for an institution to do something that’s right and correct.

Alexis Pedrick: Penn formed a repatriation committee. Meanwhile, they moved parts of the collection out of the classroom and into storage. While this was happening, Paul was still working on his PhD and teaching undergraduate anthropology classes, and he was learning things from his students.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: I remember one student whose parents were both, Nigerian immigrants, and he was the youngest student in the class, and very shy. And he asked me after one class why it was that his seat was next to a skull on the shelf, inches from him as he sat during class. And why that skull said “Negro born in Africa” on a label pasted on its forehead. And so I explained what Morton was doing, why he collected those skulls, why he labeled them the way he did, why he measured them, and at a certain point I could see on his face that more information was not making this better, contextualizing this more fully didn’t justify it. And I think experiences like that were important in helping me recognize that the kind of way in which I was trained to view human remains as scientific objects was highly limited.

Alexis Pedrick: At this point Paul was more familiar with the Morton collection than maybe anyone else in the world. And he was starting to realize the responsibility that came with that knowledge, and something struck him. Up until this point, the repatriation conversation had really just focused on that sub-group of about 50 skulls, the Africans who had been enslaved in Cuba. And Penn’s action steps were all very specific about the skulls of enslaved people. But what about the other skulls? Paul had been researching another sub-group that belonged to 14 black Philadelphians, likely Morton’s patients at the Almshouse. They might have been free when they died, but they could have been enslaved at some point. So, in February, 2021, Paul wrote a report and posed a question—

Paul Wolff Mitchell: What do you do if you have already made a commitment to bury the remains of enslaved people, or work toward that end, but you’re only talking about the remains of people who died while enslaved? What do you do when there may have been people who may have been enslaved at some point in their lifetimes? Or more broadly, how do you think about the entire white supremacist, scientific, racist, anti-Black project of which Morton was a part, which served in explicit ways as a justification, as an apology for slavery? How do you think about the remains of any Black people that were collected toward those ends still on display, still kept in a museum? These were questions I had to grapple with myself because I had worked in that museum and with those collections for a long time. But to my mind, I don’t think the questions can be ignored.

Alexis Pedrick: Paul knew that the repatriation committee was going to make a statement soon.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: And that’s of course why I released it when I did, I was like, they’re making decisions. They’re having a committee.

Alexis Pedrick: Abdul-Aliy got wind of the report and wanted to make it public.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: They called me and said, ‘I would like to write something about this for the Inquirer. Can you explain some more, give some more detail?’

Alexis Pedrick: Abdul-Aliy wrote another op-ed for the Inquirer and included a PDF of Paul’s report with. The article got a lot of attention and Abdul-Aliy helped organize a protest calling for all the skulls in the Morton Collection to be repatriated. Abdul-Aliy asked Paul to speak, and he did. On April 8th, 2021, a huge crowd of protestors gathered.

VanJessica Gladney: They were angry. And there were people who were bringing, someone did a libation ceremony to like bring kind of an ancestral presence to join us in the protest. And it was kind of a shocking but also very important reminder that this is more than just, you know, a grade. This is more than just like a project with a three prong like presentation. This is about people who were alive and whose remains have been disrespected, and people who are alive and who want to see the university, who occupies a huge part of this city, actually have a respectful relationship with this city.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: That evening, or maybe the day after, Penn announces the recommendations from that first committee about repatriation, and so it was big news. You know, Penn has decided to repatriate the Morton Cranial collection.

Marc Lamont Hill: The Penn Museum in Philadelphia is issuing an apology for its collection of 1300 skulls, including those…

Alexis Pedrick: It was a huge win. But Abdul-Aliy didn’t get to celebrate for long. Just days later, they got an email from an acquaintance who worked at another Philadelphia museum.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: She reached out to me an email thanking me for the work that I was doing and saying that she has some disturbing information that she wants to share with me. Do I have time over the weekend to have a conversation.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Three. The Move Remains.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: She told me that she had gotten information from people at Penn Museum that they were in possession of contemporary remains of black children who were, uh, murdered in the MOVE bombing.

Alexis Pedrick: MOVE is the name of a radical black liberation group that formed in West Philadelphia in 1972. The group combined the revolutionary ethos of the Black Panthers with a back-to-the-land communal lifestyle. All right in the middle of dense, urban, West Philadelphia.

MOVE confrontation in Phila: The media has called MOVE a back-to-nature group of radicals. The human species at its lowest form, and finally wrote the word MOVE means nothing at all.

Alexis Pedrick: MOVE members had a deep distrust of the government, especially the police.

MOVE confrontation in Phila: Philadelphia is a city whose Black population has tripled since the Second World War, in the wake of the civil unrest of the sixties. Then police commissioner Frank Rizzo ran for mayor on a law and order platform and won. The year Rizzo took office in 1972, was the same year that the MOVE organization began to mobilize. Year after year MOVE’s encounters with the police ended in injuries and arrest. They reacted by strengthening their religious discipline and securing their homes from intrusion.

Alexis Pedrick: Years went by like this and the antagonism grew, and then something unimaginably horrific happened in 1985, May 13th, 1985.

Let the Fire Burn: Years of conflict between the city of Philadelphia and a small urban group known as MOVE ended in a violent day-long encounter. It was one of the most devastating days in the modern history of this city. The big story tonight is the effort to evict MOVE. The effort has turned into a disaster.

Alexis Pedrick: The police flooded the house with water and then tear gas. They blasted it with automatic weapons and in the end dropped a bomb on it from a helicopter. They killed 11 people: six adults, and five children. During that phone call, Abdul-Aliy learned that the remains of two of these children were believed to have been in a lab at the Penn Museum for decades. Their names were Katricia Dotson and Delisha Orr. When they were killed in 1985 they were 14 and 11. How did their remains end up inside of a museum? Multiple reports, commissioned by Penn and the city, have tried to answer this question since this all came to light in 2021. We spoke with Keir Bradford-Grey, a lawyer hired by the city to investigate where the medical examiner’s office went wrong. And it all started with how difficult it was to identify the victims.

Keir Bradford-Grey: This was going to be a really hard task from the very beginning, based on the response, the initial response.

Alexis Pedrick: The medical examiner’s office didn’t go to the scene immediately like they were supposed to. And the scene itself wasn’t treated appropriately or with respect.

Keir Bradford-Grey: But also allowing the scene to be desecrated in such a manner that you could not identify whose body parts, you know, came from whom, was I would think, red flag number one. After looking at it I would’ve had grave concerns about the medical examiner’s office in 1985 really having the ability to do the necessary and proper work so that the identifications as well as the manner and cause of death could be trusted, and credible throughout history.

Alexis Pedrick: Robert Segal was the pathologist in charge of the case, and he needed help identifying the victims. So right away he called in an anthropology professor at Penn named Alan Mann, who brought along his graduate student, Janet Monge.

Keir Bradford-Grey: Dr. Mann and Dr. Segal, I think had a good working relationship.

Alexis Pedrick: Both Janet Monge and Alan Mann were stuck on the bones of a victim that had been assigned the label B-1. They claimed that they couldn’t match the age to anyone who had been living in the house. Meanwhile, a special commission had formed to investigate the MOVE bombing itself, and they wanted rapid answers.

Keir Bradford-Grey: And the medical examiner’s office wasn’t equipped to give rapid answers for a tragedy of this magnitude, and highly visible, not only in Philadelphia, but across the country. And they wanted people to kind of solidify, you know, give us an identification so that there was some closure and we could move forward.

Alexis Pedrick: The commission brought in their own experts, some of the top forensic pathologists in the country, and Alan Mann and Janet Monge were asked to leave.

Keir Bradford-Grey: They were involved in the very beginning for a few days, and then when the team came in, they kind of kicked everyone out. I think that left a bad taste in a few people’s mouth.

PSIC audio: Mr. Wise, would you swear in the witnesses please?

Alexis Pedrick: The team testified before the Philadelphia Special Investigation Commission.

PSIC audio: State your first names and spell your last, please, please Ali Z. Hameli, H A M E L I.

Alexis Pedrick: The new team concluded that the bones of victim B-1 belonged to Katricia Dotson, known to her MOVE family as Katricia Africa, who they called Tree Tree or Tree.

Ali Hameli from PSIC audio: Body B-1 only had about half of the thigh and the thigh bone and half of the pelvic region. That was all that was available. These are the three lines showing this particular bone gradually coming together and fusing. Those lines still were not completely fused, and that was one of the basic information that determined that was a young girl, 13 to 15 years of age. It is my opinion that most probably the remains are those of Katricia.

Alexis Pedrick: All of the children’s next of kin were notified and given their remains—or so they thought. It’s clear now that Katricia’s family never got all of her remains, and no one knows for sure if they even got any of them because the MEO pathologist Robert Segal gave at least some of those B-1 bones back to Alan Mann, even though he signed her death certificate and officially stated that B-1was in fact Katricia Dotson.

Keir Bradford-Grey: Dr. Segal even wrote a letter to the commission saying, ‘I can’t say I totally agree, but it would be absolutely unreasonable’ I think that was the exact words, ‘for me not to agree with the expert medical panel that was brought in.’

Alexis Pedrick: But clearly when he gave the remains back to Alan Mann, he had changed his mind, and we still don’t really know what was motivating him. Robert Segal has refused to talk to anyone.

Keir Bradford-Grey: I mean, he was like the witness of the century, right? We wanted to interview him so bad. He was there, and he’s the one that started the chain of events, and we wanted to understand why. And he could have cleared up so many ambiguous questions, but he absolutely refused to be a part of it, and he said to me quite bluntly, ‘I have no interest in talking about something that happened so long ago. Don’t call me again.’ Click. And that’s that last we’ve been able to, uh, even hear his voice,

Alexis Pedrick: But Keir has her own theory about what happened.

Keir Bradford-Grey: This became, to me, a battle of ego versus a search for the truth. Because if it were for the truth, we wouldn’t have 35 years go by with still no answers and still no real developments on identifications, if that’s what they were claiming that they had these for .

Alexis Pedrick: Alan Mann left Penn in 2001. Janet Monge was still there. At this point an associate professor in the anthropology department and a curator in charge of the physical anthropology collection in the Penn Museum, which included the Morton Skulls. And those B-1 bones that Robert Segal gave to Alan Mann had been left with her. Robert Segal never asked for them back. Monge was still doing research on them in the hopes of identifying them, even though many forensic experts and the official record positively identified them as Katricia Dotson. Monge used the bones as teaching tools, including in an online forensic course called “Real Bones: Adventures in Forensic Anthropology.” The videos from that course were taken off the web in 2021, but Distillations got a hold of them.

Real Bones: Adventures in Forensic Anthropology: Today we’re actually gonna look at a, an actual forensic case from here in the city of Philadelphia. The bones actually are very worthy in a study sense.

Alexis Pedrick: In the video, Janet Monge displays a few different bones on a black table.

Real Bones: Adventures in Forensic Anthropology: What I’m gonna do actually at this point is show you the remains of one of the individuals and it is somewhat of a contentious individual.

Alexis Pedrick: There’s a student with her who’s also been researching the B-1 bones for her senior thesis.

Real Bones: Adventures in Forensic Anthropology: Do you think that, um, you’ll be able to come to a conclusion relatively soon? I hope so. This is a case that’s been actually in the lab for, gosh, about 35 years. Something like that, and we’re still sort of tracking it down.

Alexis Pedrick: All these years later, Monge and Mann still disagree with Hameli’s findings. They think that the B-1 bones had to belong to someone older. Mann estimated 20, but there wasn’t anyone that age in the MOVE house. Behind the setup are the Morton skulls, which serve as a sort of artfully blurred out backdrop. Rows and rows of skulls in glass cabinets facing the camera. It’s almost like they’re watching this bone demonstration too. The MOVE bombing has left an indelible stain on Philadelphia almost four decades later. The pain is still fresh in the minds of so many people. It hits hard for the family, of course, but also the people from the neighborhood. Abdul-Aliy was an infant at the time, but they can describe their mother’s memory of that day like it’s their own.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: She remembered exactly where she was and she remembered the smell right of, of the, the smoke and hearing the noise and from what happened.

Alexis Pedrick: So when they got that phone call from their acquaintance, they couldn’t believe what they were hearing. The children’s remains were at Penn 36 years later.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: And so I, I was really shocked. I cried. I, I was stunned. I kind of just remained silent for a bit. And then after I kind of absorbed what she was saying, I was trying to understand, one, how she heard about this, you know, like why would, um, they have the remains of black children? And what she wanted me to do about it? You know, that was one of my first questions, like, what do you want me to do with this information? This is heavy. And she said, ‘you know, I want you to write about it because I feel like you’ve, you know, written about Penn Museum and their possession of, you know, black ancestors. I feel like you’re the appropriate person to write about this.’

Alexis Pedrick: Abdul-Aliy was overwhelmed by this information, but they decided to do the story. And their article in the Inquirer helped break the news to the world.

NBC Philadelphia: One of the saddest days in Philadelphia history is right back in the spotlight, but the focus tonight is on the remains of some of the children who were killed in that bombing and how it appears they were used in classes to teach Ivy League students.

Alexis Pedrick: Once the article was out, Abdul-Aliy went back to the same site outside the Penn Museum to protest again. You can hear in their voice how tired they are.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: So about 35 years since they were murdered by the state, they were held parts of them, parts of their sacred. We’re held in a box. This is disgusting. This is gross. This is not normal. This is not right. This is not okay.

Alexis Pedrick: The Morton skulls and the MOVE remains were so clearly connected in Abdul-Aliy’s mind.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: So you just learn more about just the desecration, honestly, of people’s remains over time. And about how it was decided that these people weren’t worthy of protection, adequate, you know, ceremony and rest. And also that we know who these remains belong to. We know as much as possible, right? Even though they have been classified by some as unidentified and how that label is used to dehumanize people and people’s remains, right? And so that they can be used for instruction devices.

Christopher Willoughby: Some tragedy happens to people who don’t have a lot of power and their remains end up at an Ivy League institution. That’s the norm, sadly, not the exception. You know, I think what’s nice is happening with the MOVE bombing remains, though, is that physical anthropologists, physicians are being subjected to the opinions of normal people who are rightfully outraged by what has been an everyday practice in those fields for hundreds of years.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: This was a heavy, heavy thing, and I was particularly upset with people like Paul, who I had just collaborated with, around an action at the museum, right, about the Morton Cranial collection.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: Abdul-Aliy called me and said, ‘I have to ask you something, do you know?’ And I said, ‘yeah.’ And they were upset. They were upset that I knew I, I hadn’t said anything. And I told them, ‘yep, I know about this.’

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: And I kind of asked like, ‘did you not think that that was important information to share with me?’ And, you know, kind of heard various reasons why, um, he, he couldn’t or didn’t want to share that information with me at the time. Um, but yeah, it was definitely devastating. And, um, again, the same kind of response that I had previous to that, which is ‘why, why?’

Paul Wolff Mitchell: I mean, to me it, it was just not a category, these were not categories I was associating in my mind at the time.

Alexis Pedrick: Paul had actually known about the move remained since 2015 when he found them in the anthropology department.

Paul Wolff Mitchell: I was, as I often did, I, I was working in the physical anthropology section and I was, uh, tidying up the lab and these remains were in a box in a cabinet. I opened up this box and, um, I saw a small occipital bone, and then I saw a few other bones and I remember seeing hip and femur and I, I, but I only looked for a few seconds, but I asked Dr. Monge then, ‘well, what is this?’ And I had, was holding the box in my hands looking at it open, and I just tilted it toward her. And she told me that those are move remains. I should put them right back where they came from. At the time I didn’t ask more questions, which is something I regret.

Alexis Pedrick: Documentation suggests that the occipital bone that Paul says he saw belonged to body G, which was Delisha Orr. But while Penn has acknowledged having B-1 remains in its anthropology lab, they’ve denied having any other remains from the MOVE bombing. It’s crucial to know whose remains exactly were held in a lab for decades, but it’s also important to keep in mind that there should have been none.

Mariel Carr: Have your views on human remains in museum collections changed at all throughout your dissertation work?

Paul Wolff Mitchell: Tremendously. You know, you’re trained primarily to see human remains of scientific objects. I was primed to see them as very discreet and I, what I mean by that is that they were, it was sort of neatly delimited like this is, this is a bone and it’s here and you can measure it and you can see it. What I came to appreciate evermore, in learning about the history of these collections, is the way in which there are invisible, but nonetheless, real connections between these remains and the communities they come from, the descendant communities that have connection to them today, and the broad historical context whereby they could be brought into museums and made into objects and other people like Samuel Morton were not.

Alexis Pedrick: When Abdul-Aliy’s story broke, it reopened the wounds of surviving MOVE members who had lost their family members. There was a press conference right after the news came to light. Katricia’s mother, Consuewella Africa was there. She didn’t speak much, but when she did, it was devastating.

Consuewella Africa: We will never get a chance to embrace our children and hug them and kiss them. We will never have that, that feeling of love, you know, to put them to our breasts because they’re not here.

Alexis Pedrick: Mike Africa Jr. Grew up with Katricia, who was like an older sister to him. He told a story about a time when the younger kids left a pile of wet clothes on the floor after playing in the snow. And Katricia quickly cleaned them up.

Mike Africa Jr.: And because Tree was the oldest of the kids, she had a lot of responsibility. You know, kids, older kids, you know, they, they take up a lot, you know? And today I found out something. As I was looking through these things and trying to understand what kind of monster would do these things. I’m looking at this, this, some of these, this paperwork that these people are sending me. And I looked, I saw—

—Take your time, baby. Take your time.

I saw Tree’s, birth Certificate.

—Take your time.

And I saw her little feet on this paper.

—Yeah, go ahead.

And I’m just looking and I just cannot. How these people will kill our people like that.

Alexis Pedrick: Penn finally returned Katricia’s remains to her family. Her mother, Consuewella Africa passed away just a couple of months after that press conference. Family members scattered both her’s and Katricia’s ashes underneath at tree at Bartram’s Garden, a beautiful historic garden in Southwest Philadelphia. And in August, 2022, Katricia’s brother, Lionell Dotson, was finally reunited with his sisters’ remains from the medical examiner’s office. Because after the remains at Penn came to light, the medical examiner’s office announced that they also still had some remains that they had never returned to the family. At this point, Lionell Dotson was the next of kin. It was an emotional reunion.

Lionell Dotson archival: I love my sisters.

—You never have to let them go again.

I don’t want to.

Abdul-Aliy Muhammad: Ultimately I come back to the importance of this story being known by descendants and of, of, of black folks, and the MOVE remains, the story around the MOVE remains, how important it is for Black Philadelphians to know. Because I feel like you can’t really reckon with something, really confront something, unless you name it and know it. Even if it’s hard, that you kind of have to like, understand the weight of it to really do something about it. And that’s what I hoped that op-ed would do. And it has done in, in all the uncomfortable ways that we’re sitting with that information and organizing around making institutions treat us and treat our people with respect.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Four. The Aftermath.

Alexis Pedrick: In April, 2021 when news of the MOVE remains broke and shocked the country, the Penn Museum had a brand new director. He started a week before the news hit, and he immediately issued an apology and called for an independent investigation of what happened. The university called Janet Monge’s actions insensitive, and her teaching duties were stripped. Paul and Abdul-Aliy made up. They still keep in touch today. And people started having very real conversations about the impact of museums having human remains. Here’s Subhadra Das again.

Subhadra Das: If there are human skulls in a museum collection, that is directly because race science was a thing, and because museum curators and craniometricians and biometricians took skulls to measure them. That is what they were doing in order to come up with theories to do with the way the human race worked, in ways that were inherently racist. And if all you’re getting, when you walk into, for example, a natural history museum is here is the natural world and here are the animals, and these are the things, this is where these animals live and these are the things they eat, and you don’t get the, ‘this specimen was shot by a colonial officer in Central Africa,’ if you don’t get the answer to the question, ‘how did these things end up here?’ You’re only getting a part of the story.

Alexis Pedrick: In 2022, Abdul-Aliy was asked to join a community advisory group to figure out what to do with the Morton skulls, but they were disappointed when Penn very quickly petitioned to rebury the 14 skulls of black Philadelphians. In early 2023 Abdul-Aliy made their case before a judge that the process should be led by the descendant community, not Penn itself, but an orphans court judge sided with Penn. At the release of this podcast Penn was on track to rebury what has become a collection of 20 skulls of black Philadelphians. Meanwhile, Penn’s report recommended forming a commission led by Black anthropologists, including Deborah Thomas, to come up with standards for ethically handling human remains in anthropology departments and ethnographic museums across the country.

Deborah Thomas: For me, museums should really be about the living and for ethnographic museums to be about the living and to be about the wellbeing and joy of contemporary communities they would need to get out of the body business. My own feeling is that there is no future scientific discovery, or potential discovery, that justifies the keeping of ancestors in these museum spaces, because none of them would have come through a process of informed consent.

Alexis Pedrick: Archeologist Michael Blakey is also on this commission. And he confirmed what the Penn investigation found: that neither Alan Mann nor Janet Monge had violated any professional or legal standards.

Michael Blakey: However, the most fundamental ethical principle is to do no harm. The American Anthropological Association to which, uh, all anthropologists are accountable has said that over and over in different ways for decades. And so the point is whether Dr. Monge or Dr. Mann had done their best to consider all those things that might do harm and to mitigate those effects to try not to do harm. And I don’t think they did that. In other words, I don’t think they met the standards of ethical practice, but they did apparently meet the standards of the law.

Alexis Pedrick: It sounds pretty shocking, right? We asked Deborah Thomas how this could be.

Deborah Thomas: I think what that means is that there are not well laid out, clear standards. If a set of standards isn’t written as a kind of guide for ethical behavior, then you can’t violate it.

Alexis Pedrick: And it makes you wonder, wouldn’t it be amazing if museums had more examples to look to? If only someone had led a successful ethical project involving human remains? But someone did, back in the 1990s, just a couple hours away from West Philadelphia. You just met him. His name is Michael Blakey, and in our next episode we’ll tell you all about it.

Alexis Pedrick: We reached out to Janet Monge and Alan Mann, but they didn’t respond to our request for comment. Mike Africa Jr. Declined our interview request, as did the Penn Museum who directed us to a statement on their website.

This episode was reported and produced by Mariel Carr with additional production Rigoberto Hernandez. It was edited by Rigo and Padmini Raghunath, and it was mixed by Jonathan Pfeffer, who also composed the Innate theme music. Distillations is more than a podcast. It’s also a multimedia magazine. You can find our videos, stories and podcasts at distillations.org, and you’ll also find podcast transcripts and show notes. You can follow the Science History Institute on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for news and updates about the podcasts and everything else going on in our museum, library and research center. The Science History Institute remains committed to revealing the role of science in our world. Please support our efforts at sciencehistory.org/givenow. Thanks for listening.