The word “Tuskegee” has come to symbolize the Black community’s mistrust of the medical establishment. It has become American lore. However, most people don’t know what actually happened in Macon County, Alabama, from 1932 to 1972. This episode unravels the myths of the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) Syphilis Study (the correct name of the study) through conversations with descendants and historians.

About Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race

“Bad Blood, Bad Science” is Episode 6 of Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race, a podcast and magazine project that explores the historical roots and persistent legacies of racism in American science and medicine. Published through Distillations, the Science History Institute’s highly acclaimed digital content platform, the project examines the scientific origins of support for racist theories, practices, and policies. Innate is made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom.

Credits

Hosts: Alexis Pedrick and Elisabeth Berry Drago

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Padmini Raghunath

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

“Innate Theme” composed by Jonathan Pfeffer. Additional music by Blue Dot Sessions

Resource List

Black Journal; 301; The Tuskegee Study: A Human Experiment

Under the Shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care, by Vanessa Northington Gamble

Descendants of men from horrifying Tuskegee study want to calm virus vaccine fears, by David Montgomery

Examining Tuskegee: The infamous Syphilis Study and Its Legacy, by Susan Reverby

Susceptible to Kindness: Miss Evers’ Boys and the Tuskegee Syphis Study

Voices For Our Fathers Legacy Foundation

Transcript

Alexis Pedrick: Hi, I’m Alexis Pedrick. Welcome to Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race. This is episode six: “Bad Blood, Bad Science.”

Hi, listeners. Let me ask you a question: when you hear the word “Tuskegee,” what do you think of? Maybe you recall the infamous syphilis study, and maybe the conversation about it in your house was like the one that took place in mine, something along the lines of, “Tuskegee was where Black men were secretly injected with syphilis by the government, and they were being used as guinea pigs to find a cure for white people, and that’s why you have to be cautious.” It was a lesson, a warning, and also wrong.

The word “Tuskegee” has come to symbolize the Black community’s mistrust in the medical establishment. It’s a myth so pervasive that there was an entire ad campaign during the pandemic.

Public Service Announcement: I’ve had someone tell me that they were concerned about getting the COVID vaccine ’cause of the Syphilis Study.

Alexis Pedrick: This is from a public health service announcement around the COVID-19 vaccines. The goal of the campaign was to convince skeptical Black Americans to get vaccinated.

Lillie Tyson Head: A lot of misinformation is out there that is causing people to think twice, or to hesitate, and one of them is the fact they think the men were injected with syphilis, and they were not.

Alexis Pedrick: One of the people involved in the campaign was Lillie Tyson Head.

Lillie Tyson Head: I am the daughter of one of the men in the study, Freddy Lee Tyson.

Alexis Pedrick: Lillie is also the president of Voices For Our Fathers Legacy Foundation, which is a nonprofit she and the other descendants of the men involved in the Syphilis Study started back in 2014. They created it as a way to humanize the men involved in the study.

Lillie Tyson Head: We would meet as family and talk and that about what had happened, and it was interesting to, uh, to see how the anger and the frustration, um, and the shame and the trauma still lingered. And so we started with healing sessions. In doing that, um, healing, doing those healing sessions, we were able, also, to talk about what we could do to make a difference and how we could change the narrative of that legacy. So we decided to do something about it.

Alexis Pedrick: Lille says this is one of the reasons she decided to participate in the vaccine campaign.

Lillie Tyson Head: A lot of the media was referring back to the- the United States Public Health Service Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male as the reason why African Americans are not participating and getting vaccinated, or in medical research. And, it has been a reason, and there is a reason for that, and it’s understandable, but it should not be used.

Alexis Pedrick: It all goes back to that word from earlier, and one you’ll hear a lot throughout this season: myth. Susan Reverby is the historian and author of Examining Tuskegee: The Infamous Syphilis Study and Its Legacy.

Susan Reverby: Tuskegee is just a metaphor for racism, that’s all that- that it means. It’s not that people have any idea what really happened there, they just know something bad happened, because most people don’t know the details. It’s been over for 50 years. So it’s more that people know that the government did something bad.

Alexis Pedrick: Even the word “Tuskegee” has become part of the myth. We, ourselves, have been referring to the study as the Tuskegee Study, but Lillie was quick to correct that.

Lillie Tyson Head: I’d like to address the name of the study as we have been known to- to refer to it, or to see it written, and that’s the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and the Tuskegee Experiment, which should never have been. It- when you place Tuskegee in front of the study, you give the ownership to Tuskegee. You give the accountability to Tuskegee, and the responsibility to Tuskegee. That was not a Tuskegee study. It was the United States Public Health Service Study, not Tuskegee. And I think that’s one of the reasons why you have this folklore, and then you also have this- this stigma, pretty much, uh, that still sorta surrounds Tuskegee because of that. The name never should’ve been that anyway.

Alexis Pedrick: So, going forward, we’ll refer to the study as the Syphilis Study at Tuskegee or the Public Health Service Syphilis Study.

When we say the word “myth” in regards to the Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, what exactly do we mean? Which part of it is a myth? Why are people so riled up about it? And, what actually happened in Tuskegee, Alabama, from 1932 to 1972?

Those are the questions we’re gonna answer in this episode, and buckle up, because the real story of the US Public Health Service Syphilis Study is complicated and messy, with a lotta shades of gray. But I’m getting ahead of myself. We should start at the beginning, or at least with the first question I had, what was the US Public Health Service even trying to do?

Chapter One. An Age Old Belief.

Freddy Lee Tyson was born in Macon County, Alabama, in 1907. He and his family were sharecroppers at a farm called the Youngblood Place. The arrangement worked like this: Freddy and his family were allowed to farm the land and, in exchange, the owner would get a share of the crops produced.

Lillie Tyson Head: He was honest. He was dedicated to his family and his extended family and to his church. He had a sense of humor, and he was a handsome man, had a handsome stature.

Alexis Pedrick: Unbeknownst to Freddy, he had congenital syphilis, which meant that he got it from his mother at birth. Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection, but it can be passed from mother to child, and it has four stages: primary, secondary, and so on. The first two stages are contagious. Freddy was in the third stage, or the latent phase, when there are no visible signs of the disease, and it’s typically not contagious.

Lillie Tyson Head: My parents had married in 1931, and I hate to think of what could’ve happened if my father had active syphilis.

Alexis Pedrick: But, just because you can’t see it, doesn’t mean it’s not wreaking havoc in your body. Syphilis can cause damage to your organs, nerves, bones, and heart. By the 1920s, scientists knew that the spirochete bacteria that causes syphilis can live in the body for years and cause blindness, dementia, heart disease and arthritis. I mean, it was a life sentence.

Susan Reverby: And there’s a- a debate going on in the medical literature about what you do with people who are past the contagious stage. So in the third, latency stage, couple of years out, are they still contagious? What should we give them? Should we treat them?

Alexis Pedrick: There was a treatment available, injections of various combinations of arsenic, mercury, and bismuth. But there were a few problems. First, it’s unclear if this treatment cured syphilis. There weren’t enough studies to conclude that. Plus, it was expensive and could take more than a year.

Susan Reverby: So the question really becomes, especially in the height of, as the depression deepens, what if you don’t have to treat? What if you don’t need to take these people who are no longer a public health risk just to themselves, should you be treating them, and should be using very few resources that people have on those folks when it might be useless? And so, there was an adage at the time among doctors which said, “If a man has survived with syphilis for 25 years, he’s to be congratulated, not treated.” So that’s, you know, it’s a reasonable medical question to ask.

Alexis Pedrick: And who was asking it? The doctors at the Public Health Service. Here’s Rana Hogarth, the author of Medicalizing Blackness, and a history of science professor. She says that while acknowledging victims like Freddy is important, naming the perpetrators is equally crucial.

Rana Hogarth: It’s good to know who was wronged by this, but I think if we’re talking accountability, you know, the students, when I teach them, they know… I, like, will put Raymond Vonderlehr or Taliaferro Clark as, like, a question on the, like, “Who did this in the study? I want you to know who this person is,” rather than- than saying, “Okay, well, m- the men of Tuskegee,” or something like that.

Alexis Pedrick: Taliaferro Clark was the US Public Health Service’s lead physician and the head of the venereal disease division. He wanted to find out what happened to patients with latent syphilis who didn’t get treatment. And that wasn’t the only thing going on. During this time, the Public Health Service was also interested in the ways the disease affected Black people differently than white people.

Susan Reverby: So the assumption was that Black people got cardiovascular complications and white people got the neurological complications.

Alexis Pedrick: This was a long-standing belief in the medical field dating back to when syphilis was first observed. You probably won’t be surprised to learn that it has some racist history. The theory comes from a doctor who suggested that white people had a more refined brain, which made them more likely to develop neurological complications.

Alexis Pedrick: To find out for sure, Clark proposed a two-armed study. Group one consisted of 400 syphilitic Black men who would not receive any treatment. Group two would be the control, and it would consist of 200 Black men who did not have syphilis, which raises a question.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: If you’re gonna look, uh, trying to look at syphilis, whether it was a different disease in Black people and white people, where’s your white control group?

Alexis Pedrick: That was Vanessa Northington Gamble, a university professor of medical humanities at George Washington University. The Public Health Service felt like they already had results from a white control group, because there was a long-term syphilis study done in Oslo, Norway. In 1891, a doctor left syphilis patients untreated. Fifteen years later, someone followed up and found 309 of them were still alive. Fourteen percent had heart disease related complications, and only 4% had neurological complications, which seems to contradict the common wisdom that Black people are the ones getting heart related complications.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: First of all, racism is very slippery. It is very malleable, so there’s always an explanation. You know, those were people in Norway, this is not American. Some of the ideas were that, “Well, we haven’t looked at Black people.” They belie- already believed what they wanted to look for. Neurosyphilis, that Black people not getting neurosyphilis because they don’t use, uh, their brains as much.

I have pointed out that if Black people got more c- cardiac symptoms, does that mean they use their hearts more? I mean, we try to explain, we try to look at, you know, particular logic, but, you know, I think what we have to understand, that it’s the logic of racism, that the goal was to show how Black people’s bodies were different.

Alexis Pedrick: So, that’s what was happening: Public Health Service doctors wanted to compare the results of their study on syphilis in Black patients to the results of the Oslo study on white patients to see how it affected the races differently. But why did they choose to do the study in Tuskegee?

Chapter Two. A Symbol of Black Life.

Alexis Pedrick: Tuskegee is a city in Macon County, Alabama, and as far as the Public Health Service was concerned, there were three good reasons for choosing it. Reason number one, the rates of syphilis in Macon County were believed to be almost 40% in some areas. We say believed because this number was from earlier samples. When doctors went back to Macon County in 1933, the numbers were actually between 18 and 19%, though that didn’t seem to matter to Taliaferro Clark.

Rana Hogarth: The government takes over and says, “This is a opportunity that we’re never gonna see again. We have hundreds of people that our survey data tells us have high rates of syphilis. Let’s go study them.”

Alexis Pedrick: Reason number two, the doctors thought they were actually helping people, and people welcomed them. Keep in mind, this was in the middle of the Depression in a rural community that didn’t have access to healthcare. And if that gives you pause, you’re not wrong.

Rana Hogarth: But, it was just one of those things where that’s where you see this racism, like, just baldly fall out of the pages of the letters from the Public Health Service, where they’re just like, “These men would never get access to medicine. They wouldn’t see a regular physician. Us offering a hot lunch is gonna be the best thing for them.”

That is actually pointing to health disparities. That is actually pointing to structural and systemic racism, right? They could only manipulate and exploit that group of men because of the poor and abject surroundings that they were kind of forced to live under. So to me, I’m like, “This is actually certainly a story about health disparities. It’s a story about racist logic.”

Alexis Pedrick: Access to healthcare was a big deal. Remember Freddy Lee Tyson?

Lillie Tyson Head: My father was meticulous about his health. He would make sure that his weight didn’t get over a certain point. When his belt, he had to move his belt to another notch, he went on a little diet, so to speak. In other words, just cutting back on the food that he was eating. And, he also believed in exercise and, uh, staying active, keeping a positive attitude, and having a strong sense of faith.

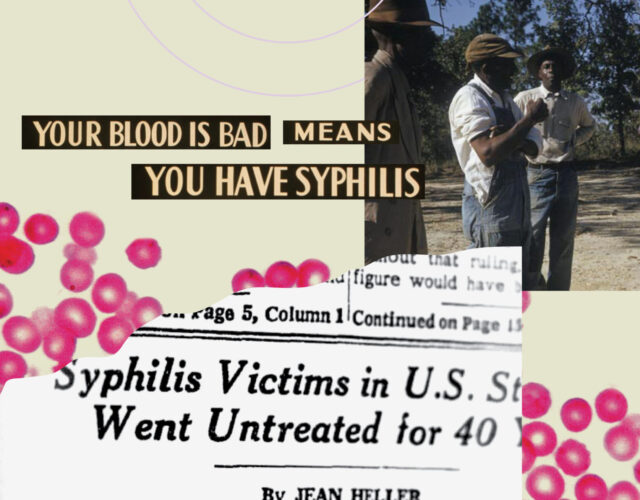

Alexis Pedrick: When Freddy was approached by the Public Health Service to participate in the study in 1933, he was never told that he had syphilis, or that he was part of a study. They just told him he had something called “bad blood”, and he was getting treatment for it.

Rana Hogarth: They would say they’ll give you tonics, aspirin, so medications, and hot lunches.

Alexis Pedrick: And that omission wasn’t an accident. It was by design. That of Raymond Vonderlehr, an up and coming physician at the Public Health Service. This is Vonderlehr.

Archival of Vonderlehr: The physician who accepts for treatment a patient with syphilis assumes a very definite public obligation. When you accept a patient, you should likewise accept the responsibility of assuring yourself that he completes the treatment schedule.

Alexis Pedrick: Vonderlehr became the head of the venereal disease division after Clark retired in 1933. The study was supposed to last for six months, maybe a year, but he successfully pushed for it to become longterm and open-ended.

Rana Hogarth: And Raymond Vonderlehr, I think, is the deception, the person who’s like, “Let’s trick these people.”

Alexis Pedrick: As crazy as it sounds, that wasn’t unusual. The standards for human experiments were different back then. Informed consent didn’t exist.

Susan Reverby: I mean, they had this completely racist view of Black folks, so they think you can’t explain this, uh, to them, so you don’t have a responsibility. And, part of that is, you know, in this period, there’s really sort of, I mean, obviously, to do no harm is still very much a part of the ethic, but there is this way in which there weren’t real rules.

Alexis Pedrick: So men like Freddy, who needed healthcare, become part of the study under false pretenses. And as Rana Hogarth explains, there are two levels of deception at work.

Rana Hogarth: So, one, in calling “bad blood” and not syphilis, there’s like deception and lie number one. Like, they did not tell them that they were studying them for a sexually transmitted disease that has severe complications if left untreated.

Two, in- in saying, you know, giving men like tonics, pills, maybe like some kind of compounds that were not as effective, the fact that you’re doing that, you’re giving them something that’s of no use, and there’s that sort of deception.

Alexis Pedrick: And, there was one more reason the Public Health Service decided on Tuskegee. It’s the most important and maybe the most counterintuitive reason.

Lillie Tyson Head: There used to be a phrase that Tuskegee was the center of all things Negro.

Alexis Pedrick: That’s Vanessa Northington Gamble again, and she’s right. Rosa Parks was born there. George Washington Carver, one of the most famous Black scientists of the 20th century was a professor at Tuskegee Institute. The Institute itself was funded by Booker T. Washington, a civil rights icon who promoted education and advised presidents. And, the Institute wasn’t just a place for Black intellectuals to thrive. It also benefited the local community.

Lillie Tyson Head: Tuskegee Institute had a well oiled public health program. They have the moveable school. They had a hospital. They had summer programs where physicians around the country came to Macon County for post-graduate training, because they couldn’t get it elsewhere. There were these mechanisms. There were these institutions. There were these physicians. There were these Black nurses and doctors there.

Alexis Pedrick: This was all very appealing to Clark. The Public Health Service doctors would be the ones to carry out the study, but he still needed doctors who treated Black patients, and access to a hospital for procedures, which brings us to one of the story’s big complications. There were Black doctors and nurses working in the study.

Chapter Three. Caring Hands.

Alexis Pedrick: When the Syphilis Study started in 1932, Vonderlehr had a problem. There was a law in Alabama that limited white nurses from caring for Black patients. He was gonna need a buffer, so he reached out to Dr. Eugene Dibble, an African American doctor who was the head of the John Andrew Hospital in Tuskegee, and this raises an interesting question. Why would a Black doctor participate in this study?

Susan Reverby: So, I wrote this chapter called “Dr. Dibble’s Dilemma” in my book, and I tried to figure out from his papers why- why would he do it? You know, why would he agree to it? And, I argued in part that he definitely was a race man. That is, he cared enormously about what happened to African Americans, but I also think he thought that diseases were different in Blacks and whites. He had been the head of the Veterans Administration Hospital also in Tuskegee, where a lot of the veterans that were there had neurosyphilis, and so he was very concerned about the disease.

And, he, um, was also a science man, and he really cared about the science, and he thought that they could prove something from the study and that might prove that people in the latency stage of the disease don’t need to be treated at all, actually, and that they could save money that way and use the limited funds that they had for other kinds of care.

Alexis Pedrick: Dr. Dibble recommended that Vonderlehr hire a beloved nurse in the community named Eunice Rivers. Rivers was born in 1900 in western Georgia, and she was no stranger to white violence. When she was a young woman, a Black man in her town killed a white police officer in self-defense and fled. The man asked her father for help, and because of this, vigilantes showed up at their home. It left a vivid impression on Rivers and her father.

Susan Reverby: He wanted to make sure that she got a really good education, so he sent her to Tuskegee to get a degree, and she ended up in the nursing program. And so, she graduates from Tuskegee in the early 1920s, and she becomes one of the first Public Health nurses in, um, Alabama. This is a point in which we don’t even have vital statistics on births and deaths in the Black community, and so she’s one of the first people starting to collect that data.

Alexis Pedrick: Once Rivers landed the job as a research assistant, she started out sterilizing syringes. As the study grew, she was charged with recruiting the men by chatting them up in schools and churches and driving them to their check ups. This is Nurse Rivers in a documentary called Susceptible to Kindness.

Eunice Rivers archival: … Profession, my duties were to get the patients in to the clinic for the examination. To begin with, I used my little Chevrolet with the rumble seat to bring these people in. And, the roads were very, very poor then. And, we brought the patients in. Every morning we had a group schedule, but I would go. It never got too bad that I had to tell the doctor that I couldn’t go.

Alexis Pedrick: This may sound strange, but the way the Public Health Service went about recruiting people was culturally competent.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: Let’s think about how physicians today, people in Public Health today, want to do clinical trials to get the cooperation of African Americans. You use African American healthcare workers. You use a Black school. You go to a Black university. You understand the cultural norms of a community. It was culturally competent in a way that abused Black people, that was used to violate people.

Alexis Pedrick: Public Health Service doctors came and went over the years, but Nurse Rivers remained constant. As the scope and the length of the study grew, so too did her role in it. For example, in 1935, the Public Health Service started offering $50 to each family to pay for a burial if they agreed to an autopsy.

Doctors believed that an autopsy was the best way to know for sure whether the patient had syphilis-related cardiovascular complications or something else entirely, like high cholesterol. It became Nurse Rivers’ job to keep the men enrolled long enough to be autopsied. She accomplished this by gaining their trust.

Eunice Rivers archival: Tell the men who come, and the funny thing about it, sometimes they would send these young doctors down, and they would beshort, you know.And if they were talking to the patients, saying, “You do so and so, and don’t you crazy, something.” And I went [inaudible 00:23:20] I said, “Now, we don’t talk to our patients like that.” and said, “They’re human. We don’t talk to them like that.” But, I had one [inaudible 00:23:30] two- two doctors to apologize.

Alexis Pedrick: She did seem to legitimately care for them men, doing things like delivering baskets of food and clothing to them on her own time, and she took her role in the community seriously. She even held classes about sexually transmitted diseases at the Tuskegee Nursing School in the late ’40s and ’50.

Susan Reverby: She becomes- what I argue in the book is she becomes kind of the private public health nurse for the families. I talked to her pastor at her church in Tuskegee, and he said everything really loved her. And, one of the men in the study told me, “You know, we always loved her.” And, you know, there just were these tight connections to her, and I think she was a really, really good nurse.

Alexis Pedrick: Like Dr. Dibble, she also believed what the Public Health Service doctors told her,that syphilis affects Black men differently than white men. She also believed that while the men were not technically getting treatment for syphilis per se, they were getting some form of medical treatment. To her, this was a net positive, because they wouldn’t have gotten medical care otherwise.

Eunice Rivers Archival: And, honestly, those patients got good medical care. This was the thing that always hurt me how they criticized, so, those people would come down here, and they’d give all kinds of glands and this- some of the things that I had never read of. They had better medical care than some of us and they could afford. Money. You know.

Alexis Pedrick: She was pointing out something that was blatantly obvious. These men had no medical care, so they were taking what they could. But, what was Rivers supposed to do? As we mentioned earlier, the treatment that was available in the 1930s wasn’t the best option, because it involved mercury, and this metal is very toxic. There was even a saying that went, “A night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury.”

Susan Reverby: In Alice In Wonderland, you know how there’s the Mad Hatter? Well, he’s called the Mad Hatter because you use mercury to stiffen the felt in hats, so often, hat makers got crazy from the mercury. So, one of the questions was, “Does the mercury cause mental deterioration, or is it the syphilis?”

Alexis Pedrick: And, that wasn’t the only problem with this treatment. As we mentioned earlier, it was expensive. It took more than a year, and there was no guarantee that it would actually work.

So, the Public Health Service rationalized that sometimes the best outcome was to leave dormant syphilis lie. And then, something happened in the 1940s that changed the equation.

Chapter Four. Under Treatment.

In 1943, Public Health Service doctor John Mahoney discovered that penicillin could be used to cure early syphilis.

Archival: Immediately, Dr. John Mahoney and his staff at the US Public Health Service Hospital on Staten Island began a series of experiments on animals. Would penicillin kill the spirochete of syphilis? How much can be used with safety? How many injections are needed to kill every lingering germ?

We can’t overstate how big this was. Penicillin could cure syphilis in just eight days. But, not all scientists were happy about it.

Susan Reverby: Joseph Earl Moore is sort of the famous syphilologist that works at Hopkins, and he’s the one who trains a lot of these people, and he sort of holds up the standard of how to do the science around this. And, when he’s- right before he dies in the early ’50s, he’s giving a talk on venereal disease to a group in- in England, and he says, “Syphilis is gonna go away with all its secrets withheld from us.”

Alexis Pedrick: In other words, penicillin is great for patients but bad for researchers. He lamented that because penicillin was now killing syphilis, all the interesting research questions that he had been asking were now irrelevant.

Susan Reverby: That’s the hard part about this. It’s like how people get so caught up in their own research that they don’t see the harm.

And, this is essentially what happened with the Public Health Service doctors. They had all sorts of justifications. Penicillin only seemed to work on people in the early stages. Many of the men in the study were in the later stages, so this miracle drug might not work. But, the ethical thing to do, and this was the medical consensus at the time, was to evaluate each patient individually to see if they could benefit from penicillin.

Susan Reverby: You know, like a lot of people do, they fell in love with their data source, and they just thought, “Wow.” And, it was a good way- you know, they’d bring the younger docs in from Public Health, and they’d bring ’em there, you know, to learn how to do the testing and how to do the blood draws, so it becomes a kind of teachable moment, right, for the Public Health Service guys over the years. I mean, everybody cycled through there, through the VD edition. It was just sort of part of what went on. And, it was seen as normative, and I think they really understood that they’d never have this chance again. And, it was just too good for their science.

So, I think it’s all of that, that it’s, uh, bureaucratic inertia on some level, but also great data set that they didn’t wanna let go of.

Alexis Pedrick: So, the men didn’t great treatment because they were thought of like a data set. The Public Health Service doctors didn’t see anything wrong with what they were doing. In fact, something else was going on in 1945 right smack in the middle of the study that should have put an end to it, the Nuremberg Trials. Second Nuremberg Trials.

Archival: The American military tribunal hearing evidence against 23 of the leading Nazi doctors.

Alexis Pedrick: During the trials, Nazi doctors were tried and convicted for the atrocities they committed against Jews in World War II. And, it served as a warning to others not to repeat these mistakes. One of the things that came out of the trial was something called The Nuremberg Code, which emphasizes patients’ rights and standardized informed consent. Basically, the ability to say no. This was a shift from the Hippocratic Oath, which applies to doctors and basically states the famous lines, “Do no harm.”

The problem with this oath is that the Nazis applied the do no harm to society. If Jews were seen as a cancer for Nazi society, it was the doctors’ job to eliminate that threat, which is why the Nuremberg Code was so important. It puts patients’ rights front and center.

Only one problem. The Nazis gave the Public Health Service doctors the perfect villain.

Susan Reverby: It was assumed that men of character, right, became physicians. So, only the crazies on an island somewhere, you know, would do bad things, or the Nazis, right? The barbarians. Or, it was- Jake Katz has a great line. He said the Nuremberg Code was seen as a code for barbarians. Right? But, if you don’t think of yourself as a barbarian, why would you need to have it?

Alexis Pedrick: This event should have given them pause, because it resembles their study. Instead, it provided them with validation. Only the most depraved, sick doctors would practice unethical science. Bad evil science is what Nazi doctors do, not American doctors in the Public Health Service.

Despite these two major changes in science and politics, the men in the study were left untreated. However, because penicillin was now widely available, it was possible for the men in the study to get access to it by going to doctors outside of the Public Health Service. During World War II, the Public Health Service actually successfully stopped the men from being drafted into the army so that they wouldn’t get access to penicillin. They also tried to keep tabs on the patients to see if they were getting penicillin elsewhere.

Susan Reverby: There are people who did in fact get to penicillin, and a lot of people after the second World War are part of- of the Great Migration of- that happens between the wars and also more after the second World War of Black people out of the rural south away from segregation into the northern cities. And, though the Public Health Service tried to follow them to see what was happening, they never told other places not to treat them. And, in the ’50s, if you got a cold, even then, and you were near anybody who was a physician, you would probably get penicillin.

Susan Reverby: So, Mr. Shaw, for example, who becomes the spokesmen for the men at the apology with President Clinton in 1997, Mr. Shaw got pneumonia in the mid-’50s, and he goes to this little hospital. It’s 10 miles outside of Tuskegee, and he gets IV penicillin for 10 days. So, the study in the end of Tuskegee is really undertreated [laughs] rather than no treatment. And, what we have to focus on, of course, is what they were trying to do, which was to keep them from getting treated, but, in fact, it didn’t always succeed.

Alexis Pedrick: The fact that some of the men were getting penicillin should have invalidated the whole study, because the data gathered is now useless. But, it gets worse. Some of the me in the control group contracted syphilis a few years into the study.

Now, these men should have been dropped from the study, but instead, Public Health Service doctors swapped the men between groups. Those who were in the control group who contracted syphilis were moved to the syphilitic group, and those who got treatment elsewhere were now part of the control group.

This is so sloppy. The study should have ended right then and there because, well, it had a bad experiment design. Which goes to show you that race science is bad science, and bad science is unethical science, because you’re putting people at risk for a study that isn’t even providing meaningful results. And yet, the experiment continued.

Chapter Five. The Leak.

This might sound surprising, but the Syphilis Study was hiding in plain sight or, arguably, not hiding at all. In fact, the Public Health Service had published more than a dozen papers on this study. So, for researchers like Bill Jenkins, it wasn’t a secret at all.

Jenkins was a Black epidemiologist working with the Public Health Service.

Diane Rowley: At that time, he considered himself to be a revolutionary, a radical.

Alexis Pedrick: This is Diane Rowley, his widow. Bill was part of a group of Black professionals who were working to end discrimination within government.

Diane Rowley: He had worked in the student non-violence coordinating committee as a student, and had been jailed with John Lewis in Atlanta and- and so was very active in issues related to civil rights and to anything related to African American freedom.

Alexis Pedrick: In 1969, he was asked to look at a series of articles about the study. He knew then they were unethical and decided to blow the whistle. This is him in the documentary, Deadly Deception.

Nova: Deadly Deception: We collected the studies, put them in a package and sent them to the Washington Post and the, um, New York Times, and so on, and, uh, waited for the major break to come. [laughs] Well, of course, it never came. We were fairly naïve about, um, how the media worked. Um, I think now we would know that we should have written a press release, and we should have, you know, had the contact, and we should have followed up and all that sort of stuff, but at this point, we- we thought all we had to do was tell America that something was wrong here, and, um, everything would be all right, and everybody would understand. And, everything was not all right, and not everybody understood, and then nothing was done.

Diane Rowley: He was very disappointed. The group was probably very disappointed. And, he actually continued to talk to other people about the study. I- uh, one of the things he mentioned to me was that he actually spoke to his supervisor about it, and his supervisor’s response was, “Don’t worry about it.” You know, “it’s- it’s- shouldn’t be a- a concern for you.” And, later on, he found out his supervisor was one of the statisticians involved in analyzing the study. And so, he just had the sense of frustration for many years.

Alexis Pedrick: But, Bill Jenkins was just the beginning of Public Health Service employees trying to draw attention to this story. Peter Buxtun was working as an investigator for the Public Health Service in the Tenderloin District in San Francisco.

Susan Reverby: So then he sends for all the reports, and he reads them, and he’s completely horrified, because here he is going out and risking his life, literally, to go trace people’s sexually transmitted diseases, and here’s the Public Health Service he works for not treating people. So, he was completely flipped out it, and he kept trying to tell people about it, and he wrote to the CDC. I mean, he’s a real irascible character.

Alexis Pedrick: Buxtun had done some graduate work on German history, so he understood what had happened in the Nuremberg trials, and he knew what the Public Health Service was doing was unethical. This is him during a television interview.

Peter Buxton Archive: The response to the moral question was more or less someone else has set this up. I’m here today. Unfortunately, it’s part of my job. I wish the whole thing would go away. Uh, nobody wanted to confront it directly because they knew it would be nationwide publicity. They knew that they would look bad. Nobody wanted to take the responsibility, and the buck did- just didn’t stop anywhere.

Alexis Pedrick: Buxtun was an unlikely whistleblower. He was a conservative Libertarian NRA card carrying member.

Susan Reverby: He’s a Republican. He’s a gun guy. I mean, I’ve stayed in his apartment. My husband and I stayed in his apartment. There were like rifles [laughs] and live ammunition in the kitchen. It was really nuts. And, I teased him once that, you know, this is the late ’60s, and I said, Geez, Peter, if you’d been a lefty and know anybody in the Panthers, this thing coulda really blown up.” [laughs] But, he wasn’t a lefty.

Alexis Pedrick: Buxtun tracked down syphilis patients during the day and read the study reports by night. He showed his supervisor some of the reports, but they responded that the men were “volunteers”, because that’s how it was written in the reports. The term volunteers implies that the men could leave the study at any time, but that doesn’t tell the whole story. You kinda had to read between the lines to understand what was actually going on.

Peter Buxton Archive The people involved really were not volunteers. It indicated that, uh, financial benefits and other medical benefits, treatment for diseases other than syphilis, had been offered these people, that, uh, burial fees had been paid or were being paid to those who were participating, and it also indicated that many of the men did not understand what the disease syphilis was and what it could do.

Alexis Pedrick: In 1966, Buxtun finally got the attention of higher ups at the Centers for Disease Control.

Nova: Deadly Deception: There was a conference that was going to be attended by the doctors, among other people, who were running the study in- in Tuskegee, and one of them, in particular, was outraged at what I had done, at what I had written.

Alexis Pedrick: This is John Cutler, a doctor at the Public Health Service, who joined the study in 1960.

Nova: Deadly Deception: And, I remember my, uh, concern, my reaction to what he was proposing.

he couldn’t wait until we got down the hall and into the conference room to begin lambasting me for what I had said, and it was, “See here, young man.”

We were dealing with a very important study that was go- going to have the- the long-term results of which were actually to improve the quality of care for the Black community. So, that these individuals were actually contributing to the work towards the improvement and the health of the Black community rather than simply serving as merely guinea pigs for the study. And, of course, I was bitterly opposed to cutting off the study for obvious reasons.

The group of guinea pigs was 100% Black. Uh, that in itself in the midst of the fervor of the ’60s, uh, was just a red flag. Uh, I- I couldn’t understand, uh, people wanting to do something like that at that time.

Alexis Pedrick: For years, Buxtun continued to complain about it to higher ups to no avail. He finally quit his job, but he never stopped talking about the Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, especially to his girlfriend, Edith Lederer.

Susan Reverby: So then he goes to law school, and then he has a girlfriend who’s a newspaper reporter, and I think- I don’t know, they were out drinking one night, who the hell knows, and [laughs] he finally explains to Edie what this story is, and she said, “You know, this is kinda interesting.” And, he’s one of these raconteur types, and he goes on and on and on and on. So, I can just imagine that everything like turned off after a while, but she heard him differently that night, and so she called her boss at AP, at the Associated Press, and then that’s- he said, “No, we need a more senior person to do this,” and that’s how Jean Heller, the reporter, got the story, and then Jean did the research and then broke the story in July of 1972.

On July 25, 1972, the Associated Press broke the story.

The Black Journal Archive: The United States Public Health Service conducted a study beginning in 1932, which continues to this day, that involved deliberately withholding treatment from group of 400 Black men who were afflicted with syphilis.

Alexis Pedrick: Lillie and her father didn’t find out about the story when it broke. At some point, Freddie’s mother-in-law, a midwife in Macon County, had advised him to stop going to the Public Health Service appointments. Freddie and his wife moved out of Tuskegee in 1960, and they eventually settled in Connecticut. He still didn’t know he had syphilis.

Lillie Tyson Head: So, he couldn’t talk about anything during those 40 years that he didn’t know about. You can’t talk about what you don’t know.

Alexis Pedrick: It was her brother who told them about it months later.

Lillie Tyson Head: Later on in that fall, my brother, Wallace, was in the Air Force, and he was stationed in Texas. He was reading the Ebony magazine, and he saw Tuskegee, and any time we would see Tuskegee, our ears would perk, because, you know, that was home. He read about the study, and he called my father, and he said, “Dad, you know anything about this study that was happening in Tuskegee?” Dad said, “No, I don’t think so.” Until about a day or so later, he received a call from the CDC, and, they told him that he was in the study. We went over to Mom and Dad’s house and tried to find out more, tried to find out if Dad knew more. He was just shocked, and you could see the pain and the disbelief in his eyes and- and hear it in his- in his voice that- to think that someone would do something like that to so many- so many people. It was a traumatic.

And- and- and there was shame. It was bad to think that, first of all, you had been used, that you had been lied to, and then you hear you are a part of this awful thing. My father became angry. He- he said he knew he couldn’t do anything about what had happened, but it was up to us to make sure that it didn’t happen again.

Alexis Pedrick: When the study was exposed, the Public Health Service officials were surprised by all the outrage. The project was so normative to them that they failed to see the problem.

John Cutler Archive: We think nothing about the fact that if war goes on and it’s in the national interest to, uh, go out and fight, a number of people are going to die, and there’s no question. And, in, you might say, the war against venereal disease, we had to get his information, and if a few people had to suffer, it’s unfortunate, but they were pro- they were doing it, uh, for the benefit of their- the rest of their race.

That was John Cutler defending the study in the documentary, Susceptible to Kindness. The project may have been so normative to the Public Health Service that they failed to see the problem, but to the world at large, that was not the case at all.

Chapter Six. The Apology.

Alexis Pedrick: In 1994, Vanessa Northington Gamble and other health equity researchers formed a committee to analyze the legacy of the study.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: And, the reason why we had come together is for some same reasons that almost parallel what’s going on with COVID, uh, 19, and that is, uh, issues around trust, uh, issues around, uh, African Americans being reluctant to be part of clinical trials.

Alexis Pedrick: In 1996, they had their first meeting at Tuskegee University to figure out next steps.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: I got to be chair, because I had the biggest mouth at the meeting, and I’m the one who said a Presidential Apology.

Let me explain something to you. I’m a fourth generation West Philly girl, so. [laughs] So, I’m- I’m kinda blunt.

Alexis Pedrick: But, not everyone was fully on board.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: So, do we need an apology? There were some people who thought that, you know, the Syphilis Study, no- no one talks about the Syphilis Study anymore. And, I remember that it was a- a Thursday, and the reason why I remember it was a Thursday is that there was a television show by the name of New York Undercover. When white people were watching Friends, Black people were watching New York Undercover. It was the number one show in Black community. And, they had this episode in there that was a fictionalized version of the Syphilis Study.

New York Undercover Archival: Those people were casualties of progress. I had no choice.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: So, that Friday, I said, “People are- in Black talk radio, Black barbershops, Black beauty salons, are gonna be talking about the Syphilis Study today.” And so, I thought it was like divine intervention so I could, you know, say “L- Look, it’s still alive in the Black community.”

Alexis Pedrick: The committee, which included Susan Reverby, wrote a report. It eventually led to President Clinton apologizing in the White House the next year.

Susan Reverby: So, in May of 1997, we had this amazing… I’m looking at my picture now, where I’m shaking hands with Mr. Clinton… um, so we got an apology at- by- while six of the men were still alive. So, five of them were well enough to fly to- to Washington, and Mr. Fred Simmons was 104, and he had never been on an airplane before. It was really amazing.

Bill Clinton Apology Archive: We can look at you in the eye and finally say on behalf of the American people, “What the United States government did was shameful, and I am sorry.”

Vanessa Northington Gamble: When President Clinton said the words, “And I am sorry,” there were audible sobs in the room because when he said, “And I am sorry,” it was almost as if he was talking not just to the men and their families, but also to Black Americans around the country.

Alexis Pedrick: But, what exactly did this apology accomplish? Some have criticized it as a happy ending to a tragedy. Rana Hogarth points to a few problems with it.

Rana Hogarth: In terms of an optics and publicity stunt, I mean they had the men in their wheelchairs, all the ones that were alive that- lined up. It was photo op, “Here it is, look, we are owning this.” But, it’s in fact putting the- the men who survived out front and saying, “Okay, these are the victims.” And, it’s always interesting to me about these apologies where I’m like, “What about the perpetrators?” I don’t think anybody knows who Taliaferro Clark is, or Raymond Vonderlehr.

We could simply point the finger at the researchers who directed the study, but as Vanessa Northington Gamble points out, that’s short-sighted.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: Uh, and it’s easy, I think, to talk about perpetrators and heroes, and I’m gonna throw some gray in here, which I think underscores the systemic problems.

Alexis Pedrick: Vanessa Northington Gamble remembers meeting a Black public health professional who knew about the study as it was going on. He told her that other Black physicians knew about it, too.

Lillie Tyson Head: I was surprised that he had never said anything about it. He had never protested about it.

Alexis Pedrick: She asked him why he didn’t do anything to stop it.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: And, he said, “The only way I can explain it,” and this is someone who was a civil rights activist, “the only way I can explain it is I saw it was research.” So, even somebody who had spent his whole life trying to improve the care of Black people had this blind eye to what was happening in Macon County, Ala-

So, that makes it gray, and it points to the systemic problems, the systemic problems of racism, the systemic problems of- of medical education, uh, the systemic problems regarding racism in medical education, public health education. Because, it’s easy to pinpoint it on Taliaferro Clark.

Alexis Pedrick: Susan Reverby says that she understands the inclination to wanna just frame Taliaferro Clark and Raymond Vonderlehr as the villains in this story, but when you do that, it kinda makes them the perfect villains. Think about the way that the Public Health Service doctors also had a perfect villain in the Nazis. It excused them from having to look inward.

Susan Reverby: I mean, the problem is in the search for the guy, m- means again we’re looking for a monster rather than understanding structural racism in medicine. So, that’s why I think in some ways the names don’t matter. You have to think about why did the Public Health Service do this, why did it keep going? Um, why did the BD division think it was fairly important? So, that’s why, you know, the talks that I give, I always give this talk, it’s called Escaping Melodrama, and I try to argue that we don’t wanna tell the story where, you know, here’s the bad guy, and then the good guys come in, and then it all goes… And it’s really a bad, crazy guy somewhere off on an island harming people.

Um, and we really wanna think about the institutions that made this happen, because otherwise, there is no change.

Alexis Pedrick: The part they do agree on is the fact that Tuskegee, the location, a once thriving place of Black life, is now overshadowed by the study.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: This was a place where these good things were happening for Black people, and that by the focus now is only on the Syphilis Study, and people don’t understand that there were other things that happened in Macon County.

Alexis Pedrick: Lillie says that the apology accomplished one big thing. It was a good step in acknowledging the wrong committed to her family and others.

Lillie Tyson Head: I felt that it was a- an honorable gesture by President Clinton to- to do- to do that, and that it did, indeed, acknowledge the wrongfulness and the evilness of that study. It showed some remorse, and it showed some accountability, and it also gave a little hope that nothing like this- nothing like that study would happen again.

Alexis Pedrick: It’s now been 91 years since the study began, 51 years since it was exposed, and 26 years since Bill Clinton apologized to the men, and yet, the ghosts of the study still linger. It’s hard to talk about in full. Even the example we gave at the beginning of the story about Tuskegee being shorthand for the Black community’s distrust of the medical establishment, that doesn’t quite give the whole picture.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: First of all, I find it problematic to be focusing on distrust, because it’s become almost like, for some people, an inherent trait of African Americans, how they don’t trust the medical community. This reluctance was racialized. We don’t- we’re not talking about white people who don’t get the vaccine. I think that it’s in- more important to talk about trustworthiness. What have medical institutions, what have public health communities, what have physicians done to gain the trust of African Americans? That trust is something that should be earned and gained and not just to be expected.

Alexis Pedrick: In other words, putting it on the Syphilis Study ignores a long history of mistreatment and avoids wading into a vast number of systemic issues that affect everything from how you’re treated when you walk into a doctor’s office to whether or not a nurse takes into account your pain.

Vanessa Northington Gamble: The Syphilis Study is only one explanation, and I think that we have to think more broadly, and I think it’s a particular laziness on the part of the medical community to only say, “It’s about the Syphilis Study.” It might be that Mrs. Jones went to a hospital in Philadelphia and was treated poorly, or that you go into a hospital in Philadelphia, and you have the head nurse be- uh, uh, be disrespectful to the Black patients who come to the emergency department.

So, I think that we need to talk about what are the elements of trust and not just use the Syphilis Study as the fallback position or the default position.

Alexis Pedrick: So, what are we left with? Well, if you’re Diane Rowley, Bill Jenkin’s widow, you don’t stop pushing. In 2021, she was invited to give a talk about her husband’s perspective on vaccine hesitation among African Americans. When she refreshed her memory on the study, she learned about the Milbank Memorial Funds’ involvement. Starting in 1935, they paid the family for burial assistance if they agreed to have their loved ones autopsied.

Diane Rowley: That sort of sent me on this search to find out if the Milbank Foundation had ever acknowledged their involvement in the study and had done anything to apologize or- or make up for their participation in it, and I couldn’t find anything. I was actually quite surprised and flabbergasted at the time that the Foundation had not publicly acknowledged their role.

Alexis Pedrick: She Googled. She analyzed the literature. Nothing. So, she emailed the foundation, and they told her that they were going to look into it. Fast forward to June 2022, the Milbank Memorial Fund officially apologized for its role in the study.

Diane Rowley: We say the Milbank Memorial Fund’s involvement in the US Public Health Service study of untreated syphilis caused harm. It was wrong. We are ashamed of our role. We are deeply sorry.

Alexis Pedrick: Yes. Sometimes, apologies can be neat little bows, but they can also help us lay ghosts to rest.

Diane Rowley: It was very satisfying to do that, and I felt as if I was honoring my husband’s legacy. You know, in some ways, it was a spiritual experience, ’cause I- it brought me, um, closer to him again in death. I- that I could con- continue to reflect on his work. He would have wanted to contact the foundation, obviously. You know, if he’d been alive, we would have been discussing the fact that, “Hey, this- this looks like something that has slipped through the cracks, and- and it needs to be acknowledged. And- and we need a response from them, a serious response that they- they recognize that the harm that they did.”

Alexis Pedrick: Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race is made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy Demands Wisdom. This episode was reported and produced by Rigoberto Hernandez with additional production by Mariel Carr and Padmini Raghunath. It was edited by me, Alexis Pedrick, and it was mixed by Jonathan Pfeffer, who also composed our Innate theme for Distillations.

Distillations is more than a podcast. We’re also a multimedia magazine. You can find our videos, stories and podcasts at distillations.org, and you’ll also find podcast transcripts and show notes. You can follow the Science History Institute on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for news and updates about the podcasts and everything else going on in our museum, library and research center. Thanks for listening.