On April 22, 1970, a crowd of 30,000 gathered on Belmont Plateau in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. It may have looked and sounded like a rock concert, but the people who took the stage that day weren’t just looking to entertain. These artists, activists, and politicians instead were there to galvanize the city’s and country’s growing environmental movement. The event, one of the largest in the nation on that first Earth Day, was the culmination of a week of activities in Philadelphia designed to promote environmental activism and build a diverse coalition that could spur political action. But these efforts to create common cause and collective action could not overcome the differences among activists, let alone the schism between Philadelphia’s young counterculture and the rest of city.

Earth Day was first proposed by Democratic senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, who envisioned a national, grassroots teach-in that would raise awareness about environmental issues and channel the spirit of anti–Vietnam War activism into the political might needed to pass environmental legislation on the local and national levels. Across the country like-minded individuals in cities and on college campuses responded to his call—planning events to educate neighbors about a growing environmental crisis and the need for broad political action. In Philadelphia these plans blossomed into an entire Earth Week of educational talks, performances, and political rallies.

Among those who spoke at the Fairmount Park event was Maine senator Edmund Muskie, who had championed pollution control since the early 1960s as chair of the Senate Subcommittee on Air and Water Pollution. To many, Muskie was the face of D.C. establishment environmentalism. Throughout the decade his committee oversaw the passage of incremental and limited air- and water-pollution control regulations, including the Clean Air Act of 1963 and the Water Quality Act of 1965, that set standards at the state and local levels.

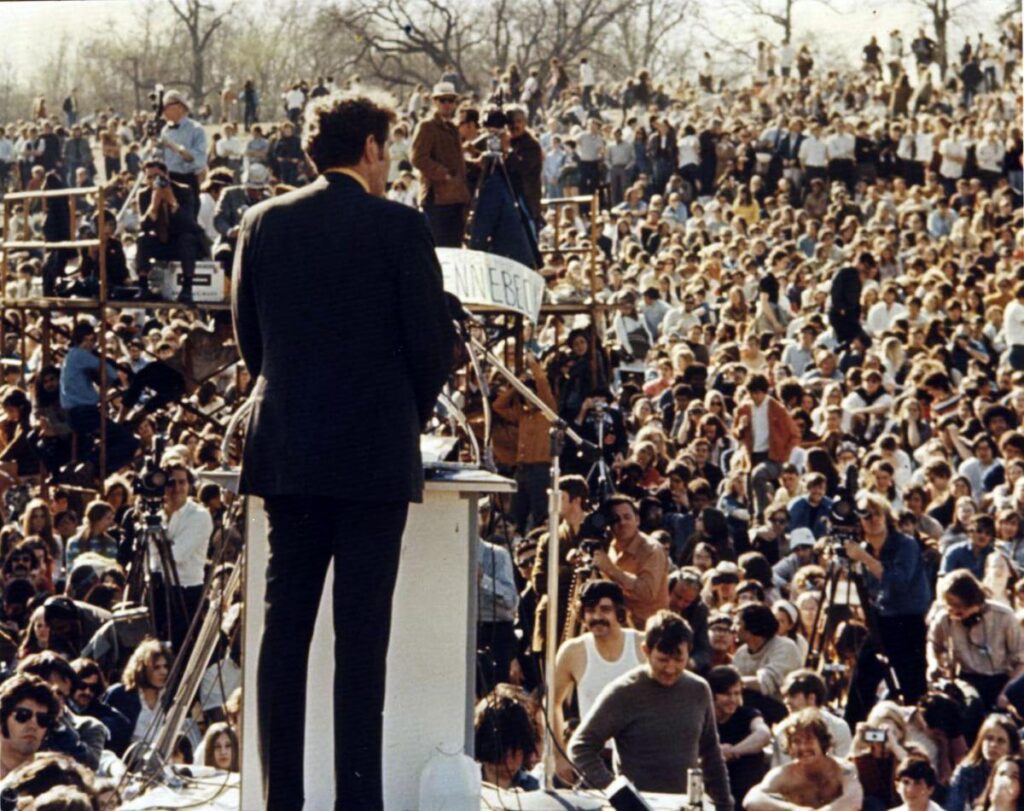

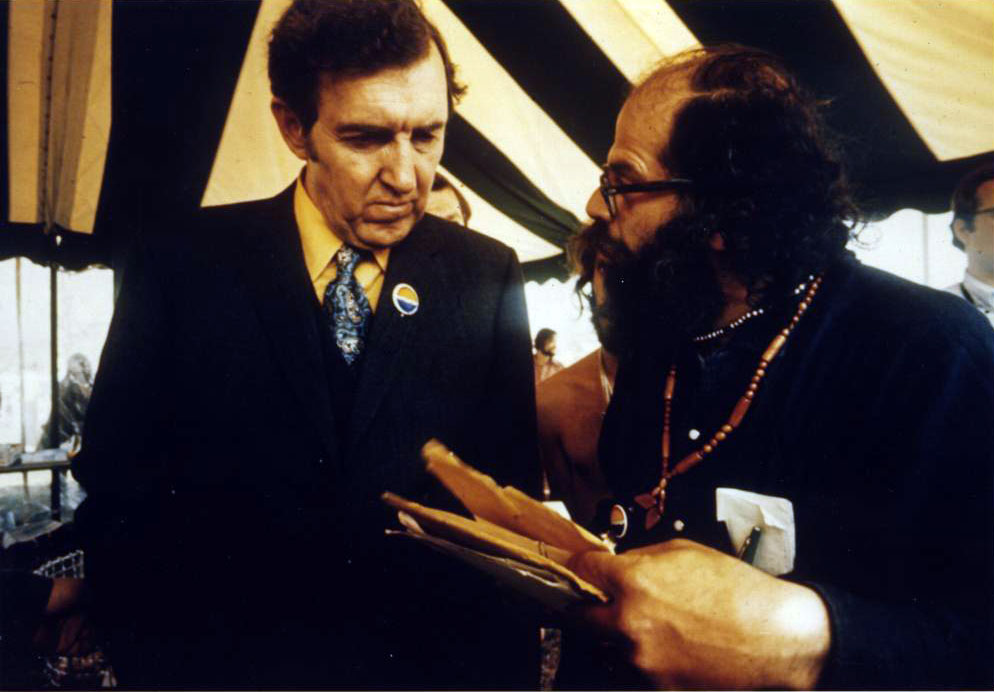

At 3:30 p.m. Muskie, wearing a paisley tie and Earth Week pin, stepped onto the small stage and addressed a crowd stretching up the rise and out to the wooded edges of Belmont Plateau. “No major American river is clean anymore,” he declared. “No American lake is free of pollution. No American city can boast of clean air.” Although it was a clear, sunny day in Fairmount Park, attendees sitting high atop the plateau could see the soot-choked city skyline, polluted by power plants, oil refineries, incinerators, and automobiles.

While the power to regulate the environment lay in the hands of federal legislators and state administrators, Muskie reminded listeners of their own power and the need to harness it for change. He told them that the power of people is demonstrated at the ballot box, cash register, courts, and public hearings. Only with public support could the Clean Air Act be adequately strengthened and the federal government given greater authority to regulate pollution.

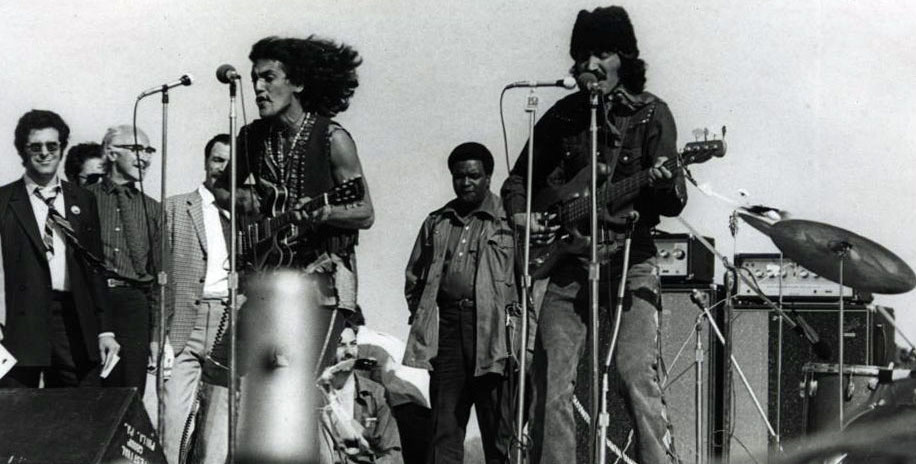

While Muskie and other politicians attracted the most ardent antipollution activists, musicians and performers pulled in the big crowds. These artists connected environmentalism to the other protest movements of the time. At Belmont Plateau, Broadway performer Sally Eaton sang “Air” from the musical Hair. (The day before, the entire cast of Hair had performed the song for a crowd of 20,000 at the city’s Independence Mall.) “Welcome! sulfur dioxide, hello! carbon monoxide,” the song calls out, before ending in a chorus of coughs. Both of those toxic gases plagued Philadelphia and many other cities in the country. At Independence Mall some in the audience wore face masks to highlight their concern about the city’s air quality.

The catchy, political melodies from Hair, which opened on Broadway in 1968, became anthems of the late 1960s counterculture and, in particular, the anti–Vietnam War movement. The latter theme percolates throughout the show as a cast of young Americans contests the government’s authority and protests the war in Vietnam. One song says of the government, “To keep us underfoot, they bury us in soot, pretending it’s a chore to ship us off to war.” For many of the war’s critics Vietnam was an assault on people and nature. As the United States increasingly used defoliants and napalm to devastating effect, the two social movements—one to end the war and the other to protect the environment—became increasingly intertwined.

Joining the Hair cast members at Independence Mall and Belmont Plateau was all–Native American rock band Redbone. The group, which would later score a hit with “Come and Get Your Love,” played politically charged songs about the war and the mistreatment of Native Americans. “Red and Blue” relays how steel, concrete, and industrial progress crushed native peoples’ way of life and sense of harmony with the land. Earth Week’s organizers were attempting a tricky maneuver: to yoke these antiestablishment sentiments to the brainchild of politicians. And these efforts extended well beyond the artists invited to Philadelphia.

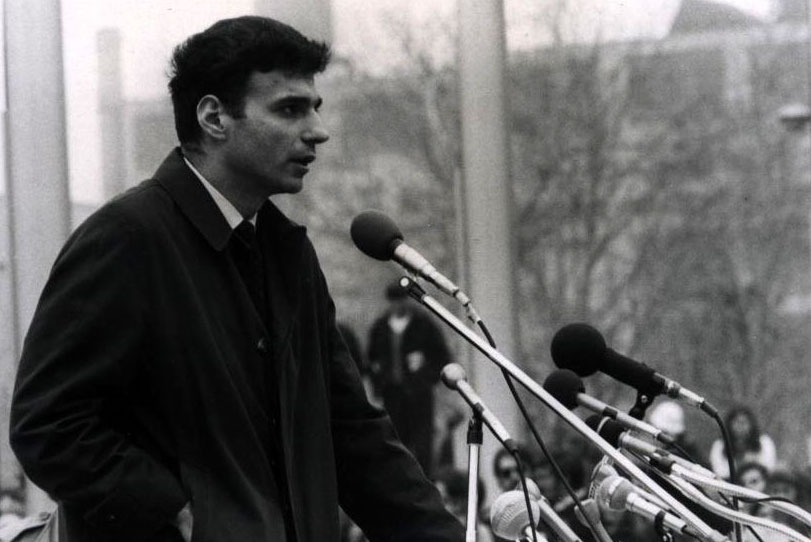

Ralph Nader had made his name as a staunch consumer-protection advocate by pushing the auto industry to make cars safer. From his perspective material consumption and environmental health were intrinsically tied. Pollution was a consumer problem, and therefore consumers had the right to buy products that did not foul the earth. Or looked at another way, cars that fouled the air with smog hurt consumers as surely as cars with faulty axles and poorly designed instrument panels.

At the Independence Mall rally Nader presided over the signing of the “Declaration of Interdependence.” Originally penned in 1969 in Berkeley, California, the declaration took on special meaning when members of the public signed it in front of Independence Hall, where the Declaration of Independence had been signed nearly 200 years earlier. In place of the injuries committed by the British king, the document listed the injustices committed against Earth by humans, including the fouling of water, the massacre and extinction of species, and acts of war. The new declaration emphasized the interconnected nature of life on Earth, and its signers entreated people to be more conscious of their individual and collective impact on the planet.

Earth Week was more than just rallies. Lecture programs brought a wide cross-section of scientists and scholars to speak at local universities. On April 18 biologist Paul Ehrlich addressed an audience of approximately 1,200 people at Villanova University, part of a “Population Day” program held with fellow biologist René Dubos. Both men espoused a controversial strain of environmentalism, one that viewed population growth as the main cause of environmental degradation.

Ehrlich had gained notoriety with the 1968 publication of The Population Bomb, written with his wife, Anne Ehrlich. The book helped infuse the concept of population control into modern environmental discourse with its prediction of global famine as a consequence of overpopulation and the resulting increase in pollution and decline in natural resources. The organizers of Philadelphia Earth Week even published a booklet encouraging people to practice voluntary population control as a way to help the environment.

Villanova’s student newspaper remarked that “the future is extremely bleak if one is to believe Dr. Ehrlich. He envisions a world groaning with the weight of millions of people and finally expiring from sheer resource exhaustion.” Ehrlich concluded his pessimistic speech with a prediction that pollution from commercial supersonic jets could set off a global cooling cycle that would produce another ice age.

Such brash pronouncements were obvious targets for skepticism, but in a column published before Ehrlich gave his talk, Philadelphia Inquirer science writer Patricia McBroom focused her criticism on his approach to environmentalism. Population and pollution are separate problems that are not causally related, she wrote. Rather, a high standard of living—not simply a growing population—creates pollution problems. Cloaking the real reasons for pollution behind the rhetoric of overpopulation could have serious consequences, she warned. Ehrlich and his compatriots’ focus on population control drew attention away from the greater need to control waste in industrialized societies.

McBroom’s critique was just one crack in an ecological coalition that Earth Week hoped to build. While calling for cooperative action from the stage, the disparate collection of pollution fighters, antiwar protesters, and consumer advocates repeatedly strained against the confines of big-tent environmentalism.

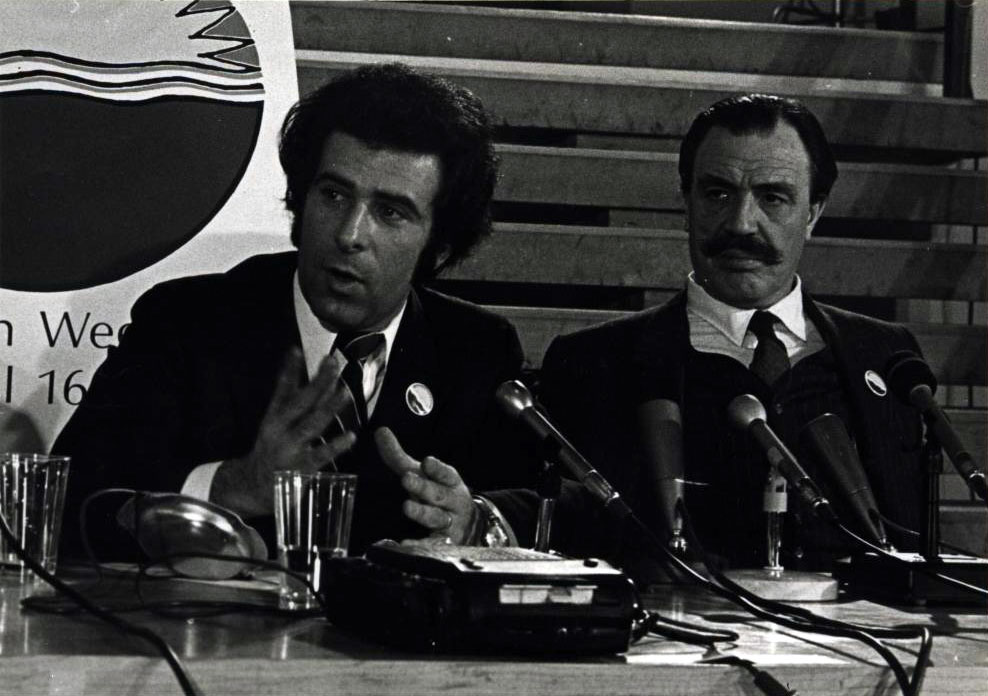

Nader, not one to shy away from confrontation, vented his own frustration. At a press conference at Temple University he branded Muskie’s environmental laws “cosmetic.” In particular Nader slammed the amendments to the Clean Air Act that Muskie had steered to passage in 1967. Nader said the legislation, commonly known as the Air Quality Act, had little effect on air quality and was too forgiving of polluting manufacturers and industries. Nader would continue this attack on Muskie through 1970 in an effort to pressure the legislator to toughen his stance against corporate polluters.

Muskie and his supporters pushed back against accusations they labeled unjustified and unfair. From their perspective the 1960s legislation was a pragmatic approach to dealing with polluting industries rather than the conciliatory approach Nader suggested it was. Nader’s criticism, however, emboldened Muskie to include stricter mandates in the 1970 amendments to the Clean Air Act to drastically reduce auto emissions. Ultimately the dispute revealed differences in viewpoint about the responsibility of industries to reduce air pollution and to pay for damage already done—a push and pull between legislators and activists that persists today.

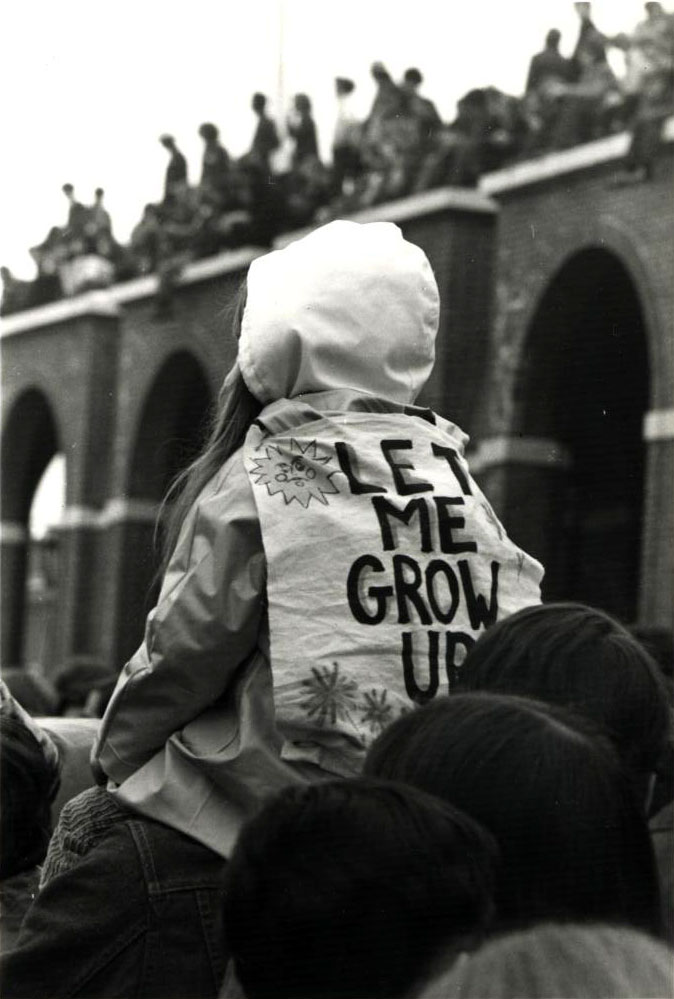

Edward Furia, the person in charge of Philadelphia’s events, leaned more toward Muskie’s point of view. He wanted Earth Week to welcome all people, a “convocation not a confrontation,” and to include all polluters, from ordinary citizens to industry representatives. He and the other leaders wanted a unifying issue easily digested by a mainstream audience: after all, everyone lived in a world affected by pollution.

Earth Week organizers were only so successful in building that unity. They had envisioned a local, grassroots assembly of diverse voices, but many Philadelphians felt excluded from the dialogue. A CBS News reporter characterized the crowd at Fairmount Park: “a few older people, a few blacks, and some of the poor—but mainly white, middle-class young people.”

Many also believed that the ecological crusade was an excuse for white citizens to abandon black people in their struggle against racism and inequality. Prominent black leaders, including community organizer Herman Wrice, gathered to talk about the issues people should really be rallying around: fighting poverty, racism, slum housing, and joblessness.

Despite these shortcomings the first Earth Day produced some clear-cut results. The environmental awareness it raised among Americans created the political capital needed to pass comprehensive clean air and clean water laws and establish the Environmental Protection Agency. Proponents of Earth Day and the modern environmental movement continued pushing for policies after 1970, including the Superfund program that allows the EPA to clean up contaminated sites across the country. Ultimately, these regulations and regulators have left the country’s air and water cleaner than they were in the mid-20th century but with a caveat.

Fifty years later the United States is still one of the world’s worst polluters. And while the country struggles to address climate change, the U.S. environmental movement still wrestles with factionalism, tensions based on race and inequality, and recalcitrance from polluting industries.

Some of today’s problems might be traceable to the first Earth Day planners’ modesty of vision. Nelson and other organizers wanted consensus-building events. But as Ian McHarg, the celebrated founder of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, noted in the lead-up to Earth Week, environmentalism required a radical rejection of contemporary values toward nature. Best known for infusing ecological planning into landscape architecture, he believed the environmental movement was revolutionary in nature and would require a fundamental change in the way people lived. By that measure we have a very long way to go.