In the 1840s a struggling medical student from Vermont wanted to make some money. With nitrous oxide as the central prop Gardner Q. Colton created a traveling road show, advertising “A Grand Exhibition of the Effects Produced by Inhaling Nitrous Oxide, Exhilerating, or Laughing Gas!” Colton turned his audience loose upon the theater stage, announcing that “only gentlemen of the first respectability” were invited to inhale the gas in order “to make the entertainment in every respect, a genteel affair.” Typical behavior at such events included jumping, dancing, and singing.

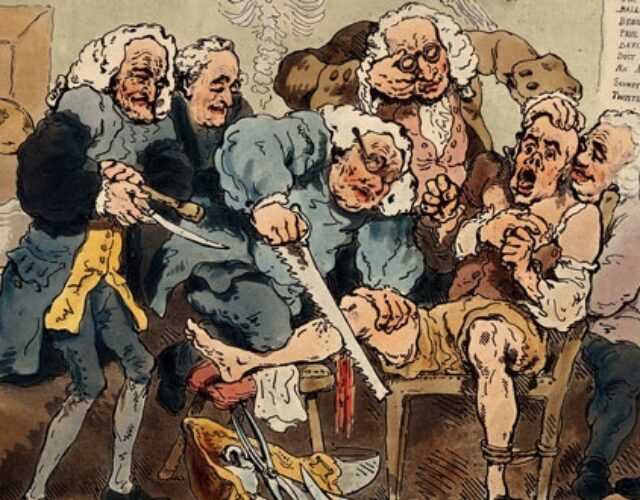

In 1843 Edinburgh chemist George Wilson found himself in a very different theater—an operating theater. He described the amputation of his injured ankle as a “cruel cutting through inflamed and morbidly sensitive parts, [which] could not be dispatched with a few swift strokes of the knife. . . . Suffering so great as I underwent cannot be expressed in words.” His spiritual anguish equaled his physical pain. “The black whirlwind of emotion, the horror of great darkness and the sense of desertion by God and man, bordering close upon despair, which swept through my mind and overwhelmed my heart, I can never forget.”

Between dancing and despair lay one of medicine’s greatest breakthroughs: anesthesia. Previous medical attempts to alleviate suffering included administering herbal medicines, opiates, or strong liquors. Some physicians even bled their patients into unconsciousness. None of these methods worked well enough to conquer the wrenching agony of surgery and dentistry—or the terror of those facing such trials.

The curious origin story of anesthesia includes laughing-gas parties in the early 1800s, bloody knees on the stage of a Connecticut theater in 1844, and three Scottish physicians passed out under a dining-room table in 1847. The advent of surgical anesthesia—the obliteration of bodily pain by chemical means—was marked by conflict and controversy. Nonetheless, within just a few years of its first use surgery and dentistry were no longer the horrendous ordeals they had once been. Anesthesia quickly became part of everyday life in the 19th century, just like the railroad and the telegraph.

The Hilarious Gas

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries medicine and chemistry advanced side by side—if haltingly at times. Joseph Priestley, who codiscovered oxygen in the 1770s, had also identified ammonia and nitrous oxide, among other gases. Physicians quickly sought out the potential therapeutic properties of these gases. An English doctor named Thomas Beddoes founded a short-lived “Pneumatic Institution” in Bristol, hiring Humphry Davy, then a rising young chemist, to oversee medical experiments with a wide range of chemical substances.

Breathing nitrous oxide produced euphoric effects, leading Davy to christen it “laughing gas.” For Davy and his contemporaries the gas offered greater potential as a mind expander—a key to unlock the Romantic imagination—than as a useful tool for medicine. At parties and fairs inhaling nitrous oxide became a new craze. Cow and pig bladders equipped with wooden spigots were filled with laughing gas and distributed. Released from the pressures of polite behavior, those under the influence behaved ridiculously. For his nitrous oxide show Colton advertised that “probably no one will attempt to fight”—a half-hearted reassurance that may have attracted people eager to witness a fracas.

In December 1844 Colton visited Hartford, Connecticut. A young dentist named Horace Wells was one of the first to rush up to the stage when Colton called for volunteers. After inhaling his share of nitrous oxide and dancing about, he came to his senses sitting in a row of chairs at the back of the stage. Next to him was an acquaintance named Sam Cooley, a drugstore clerk, with blood on the knees of his pants. When Wells pointed this out, Cooley was startled. He had collided hard with a wooden settee on the stage, but felt nothing. Wells had an audacious thought: what if the gas could be used to reduce pain in surgery and dentistry? After consulting with friends and colleagues he proposed an experiment to Colton.

Wells was to be the first guinea pig, with Colton providing the gas and a fellow dentist extracting a stubborn wisdom tooth. After the experiment Wells exclaimed, “It is the greatest discovery ever made! I didn’t feel it so much as a prick of a pin!”

Under the Ether Dome

Wells had indeed made an amazing discovery, but he faced both skeptics and detractors. His demonstration of tooth-pulling under nitrous oxide at Massachusetts General Hospital in January 1845 failed to convince doctors and medical students when his patient moved about and groaned during the procedure, even though the man insisted afterward that he had felt no pain. And a former business partner, a fellow dentist and doctor named William T. G. Morton, soon tried to take credit for proposing an inhaled anesthetic. Morton’s chosen substance, however, was quite different from nitrous oxide: ether or diethyl ether, often called sulfuric ether at the time. Mention of this clear, flammable, volatile liquid goes back to at least the 16th century, when it had been called “sweet oil of vitriol.” Many remarked on its therapeutic properties, and a Georgia doctor named Crawford Long even used it as an anesthetic in 1842, though he only published his findings later. Like nitrous oxide, ether found popularity as a recreational drug, with medical students and others holding “ether frolics.”

Morton, a relentless self-promoter and schemer, stole money and ideas from others, then tried to take sole credit for shared innovations. Despite his shady character he played a leading role in the first public demonstration of ether as a general anesthetic for surgery. This momentous event took place before a large audience on October 16, 1846, in the operating amphitheater at Massachusetts General Hospital, now memorialized as the “Ether Dome.” Morton’s patient breathed through a custom-built inhaler apparatus consisting of a glass globe, a sponge soaked with a mixture of ether and oil of orange, and tubes and valves. The dean of the Harvard Medical School then cut out a tumor from the unconscious patient’s neck. When the man awoke, he reported feeling as though his neck had been scratched. “Gentlemen, this is no Humbug,” proclaimed the dean.

While the effect of the ether was quite real, Morton’s efforts to disguise the true nature of the anesthetic substance were deceptive, and designed to ensure his rights to an ordinary gas. He added oil of orange to hide ether’s characteristic odor in hopes of obtaining a patent on what he called “Letheon.” In addition, he commissioned the inhaler both to impress the audience and to provide an opportunity for another patent. Medical practitioners soon realized that “Letheon” was simply diethyl ether. Its use for surgery, dentistry, and childbirth spread rapidly, and Morton failed to make a fortune from the discovery.

Ether also seeped into popular culture, fascinating people with its ability to vanquish pain. As Scottish doctor Douglas Maclagen proclaimed in his comic “Ether Song” of 1850 (set to the tune of “Yankee Doodle”):

In physic, is most sure, Sir;

“The vapours” once were a disease,

But now they are a cure, Sir.

So if aches and pains should torture you,

On Ether spend your money;

You may be drawn and quartered too,

And only think it funny.

In 1847 French cartoonist Charles-Amedée de Noé, known by his pen name of Cham, presented satirical vignettes of the drug in the journal Le Charivari under the mock-serious title “Medical Studies of Ether.” Dueling swordsmen engage in an “affair of honor” with bottles held to their noses while they ravage each other with their rapiers, oblivious to the pain; a boy receiving a fierce whipping sniffs at his bottle, a rapturous expression on his face; another man, waking up to find a wooden leg by his bedside, is appalled to discover that his real leg has been amputated while he slept.

Two of Cham’s vignettes address dentistry. In one, a man in a dentist’s chair dreams of being onstage, kneeling before a lovely ballerina who brings him a garland of flowers. In another, a man, confronted upon waking with a platter piled high with his own enormous choppers, regrets the “inconvenience” of encountering an overly enthusiastic tooth-puller. As more and more people experienced surgery and dentistry in an etheric haze, such cartoons may have helped to alleviate anxiety about this new, mind-altering substance and its effects.

The Sweet Blessing

The next major breakthrough in anesthesia came in 1847. In an elegant dining room in Edinburgh, Scottish surgeon and obstetrician Sir James Young Simpson ran a series of experiments to find inhaled painkillers that would be less smelly and flammable than ether and have fewer side effects. In an unusual twist on the standard gentleman’s routine of after-dinner drinks, Simpson and his assistants, George Keith and Matthew Duncan, gathered on Thursday evenings to sniff different chemical compounds and determine their effects, a logical, if dangerous method of drug testing in an age before clinical trials. Simpson did not choose his chemicals randomly; he focused on substances with “a more fragrant or agreeable odor” than ether and on volatile compounds that would evaporate at room temperature, thus becoming absorbed into the bloodstream through the lungs.

On the evening of November 4 it was chloroform’s turn. This organic chlorine-based compound had been synthesized in the 1830s by three men working in different countries: John Guthrie, a physician in upstate New York; French chemist Eugène Soubeiran; and famed German chemist Justus von Liebig. Though Guthrie’s “sweet whiskey” had enjoyed a brief vogue as a sipping tonic in his town of Sackets Harbor on Lake Ontario, the clear, heavy liquid seemed to have little practical use. Still, it fit Simpson’s guidelines. The three Edinburgh doctors poured out the chloroform, raised their glasses to their noses, and breathed in deeply. A sweet smell filled the air, and the younger physicians became lively and talkative.

“This is far better and stronger than ether,” Simpson thought. The next he knew, he was looking up at the ceiling, with noise and confusion all around. Duncan had collapsed under a chair, snoring loudly, and Keith lay on his back under the table, kicking it violently despite his unconsciousness. After gradually waking up and struggling back into their seats, the doctors were eager to experiment again—though more cautiously this time. Other family members watched these remarkable events. After inhaling the chloroform herself, Simpson’s niece-in-law called out, “I’m an angel! Oh, I’m an angel!” before folding her arms and falling asleep at the table. The group continued to sniff the chloroform until it all evaporated.

The experiment was a grand success, and Simpson and his colleagues lost no time in having large supplies of chloroform manufactured to use on their patients. Its use spread rapidly, as it was easy to obtain and administer and less harsh in its effects than ether. Simpson wrote extensively in defense of the substance, countering doctors and clergymen who argued that pain was necessary for the body and ordained by the Bible. He delivered one of his pithiest ripostes in an 1848 exchange with “an Irish lady.” She chastised him by saying “how unnatural it is for you doctors in Edinburgh to take away the pains of your patients when in labour.” He responded, “How unnatural . . . is it for you to have swam over from Ireland to Scotland against wind and tide in a steamboat.” For Simpson and his supporters relieving pain was as great an innovation as steam power. Both inventions seemed to prove 19th-century ideas about boundless technological progress and the perfectibility of humankind.

Nevertheless, objections to anesthesia—especially when used for women in labor—continued. Soon, however, chloroform received an unexpected supporter. Queen Victoria and her consort Prince Albert requested the compound for the birth of their eighth child, Prince Leopold, in 1853. John Snow administered the drug, using a few drops on a simple handkerchief rather than the inhalers and masks then on the market. The queen, who remained conscious throughout the procedure, recorded in her journal that the effect was “soothing, quieting, delightful beyond measure.” She received the drug again in 1857 for the birth of Princess Beatrice, her ninth and last child. When her oldest daughter Princess Victoria had her own first child in 1859, the queen rejoiced, “What a blessing she had chloroform.”

Anesthesia soon found its way onto the battlefield, and played an important role in the American Civil War. Despite popular conceptions of wartime medicine as bloody butchery with only whiskey to kill the pain, records show that more than 108,000 Civil War surgical procedures on both sides of the conflict were performed by surgeons using anesthesia, mainly chloroform.

Anesthesia soon found its way onto the battlefield, and played an important role in the American Civil War.

The Union blockade of 1861 to 1865, which cut off the South from major pharmaceutical manufacturers, set off a wave of medicine smuggling. During a battle at Winchester, Virginia, in May 1862, Confederate General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson scored a major coup when he captured 15,000 cases of chloroform, along with other Union medical supplies. A year later, when Jackson himself received the drug for the amputation of his badly wounded arm, he exclaimed, “What an infinite blessing!” He repeated the word blessing until he lost consciousness. Afterward he described being under chloroform as “the most delightful physical sensation I ever enjoyed.” The general testified to the compound’s ability to transform even the most gruesome ordeal: “At one time I thought I heard the most delightful music that ever greeted my ears. I believe it was the sawing of the bone.”

Both Queen Victoria and General Stonewall Jackson found chloroform to be a gift. However, as the 19th century proceeded, people reported a variety of experiences under the influence of anesthetics. In the 1870s English poet William Ernest Henley wrote movingly about the disorienting sensations of chloroform, along with the surgical patient’s loss of autonomy (see below). Later, around 1912, Richard T. Cooper, an English artist who created a series of melodramatic paintings of fearful diseases, adapted the ancient imagery of demonic possession to convey his feelings of being chloroformed for an appendicitis operation. Cooper depicted himself naked and helpless, fists clenched, lying on a platform suspended in a dark, swirling void. Small, bald, demonlike creatures swarm over him. Two drive a corkscrew into his side, representing the sharp, agonizing pain of a ruptured appendix. Another perches on the victim’s torso, squeezing his skull with pointed pincers. This demon seems to evoke the pressure and throbbing in the head some felt under the influence of chloroform. Several of the smaller demons devise a hellish concert: one beats a drum at his ear, while others blast trumpets and clash cymbals, evoking the magnified heartbeat and confused cacophony of noises described by Henley. A ghostly, distant moon—perhaps a light in the operating room—and a fluttering bat complete the sinister scene.

You are carried in a basket,

Like a carcase from the shambles,

To the theatre, a cockpit

Where they stretch you on a table.

Then they bid you close your eyelids,

And they mask you with a napkin,

And the anæsthetic reaches

Hot and subtle through your being.

And you gasp and reel and shudder

In a rushing, swaying rapture,

While the voices at your elbow

Fade—receding—fainter—farther.

Lights about you shower and tumble,

And your blood seems crystallising—

Edged and vibrant, yet within you

Racked and hurried back and forward.

Then the lights grow fast and furious,

And you hear a noise of waters,

And you wrestle, blind and dizzy,

In an agony of effort,

Till a sudden lull accepts you,

And you sound an utter darkness . . .

And awaken . . . with a struggle . . .

On a hushed, attentive audience.

As Henley’s poem and Cooper’s painting suggest, anesthesia had a dark side. Such powerful drugs had the potential to cause real harm, and since medicines were not regulated at the time, anyone could purchase them. Of the three major anesthetic agents nitrous oxide was the least widely abused because of the difficulty of producing and storing the gas. In addition to sniffing ether, some drank it in liquid form as a cheaper and faster alternative to whiskey, though it could cause depression, hallucinations, and irritability. Ether’s flammability was a further danger, with smokers occasionally setting themselves on fire after indulging. Chloroform was perhaps the most dangerous of the substances, partly because it was easy to use. It could be addictive, and overdoses could kill. Criminals used it to aid murders, rapes, and robberies. And it was criticized for sparking erotic desires, especially in women.

Research into anesthesia developed rapidly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with newer, less hazardous substances and techniques gradually supplanting the first painkillers. Of the three earliest inhaled anesthetics, nitrous oxide is the only one still widely used today. Anesthesia is now a highly advanced medical specialty conducted by expert practitioners, but exactly how and why anesthetic agents work in the human body largely remains a mystery. Perhaps future researchers will be able to probe the woozy secrets of painless dreams with greater clarity.

The author would like to thank Joseph Rucker for his advice and comments.