Timothy Winegard. The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator. Dutton, 2019. 496 pp. $28.

It’s October 1943, and the Nazis have just lost Italy to their enemies, the Allies. Infuriated, Hitler dispatches “General Anopheles,” his most ruthless fighter, to finish off the turncoat Italians and their American, British, and Canadian friends. The old general is notorious for leaving long trails of death and misery in her wake. Her thirst for blood is insatiable.

Yes, billion with a B. General Anopheles is merciless.

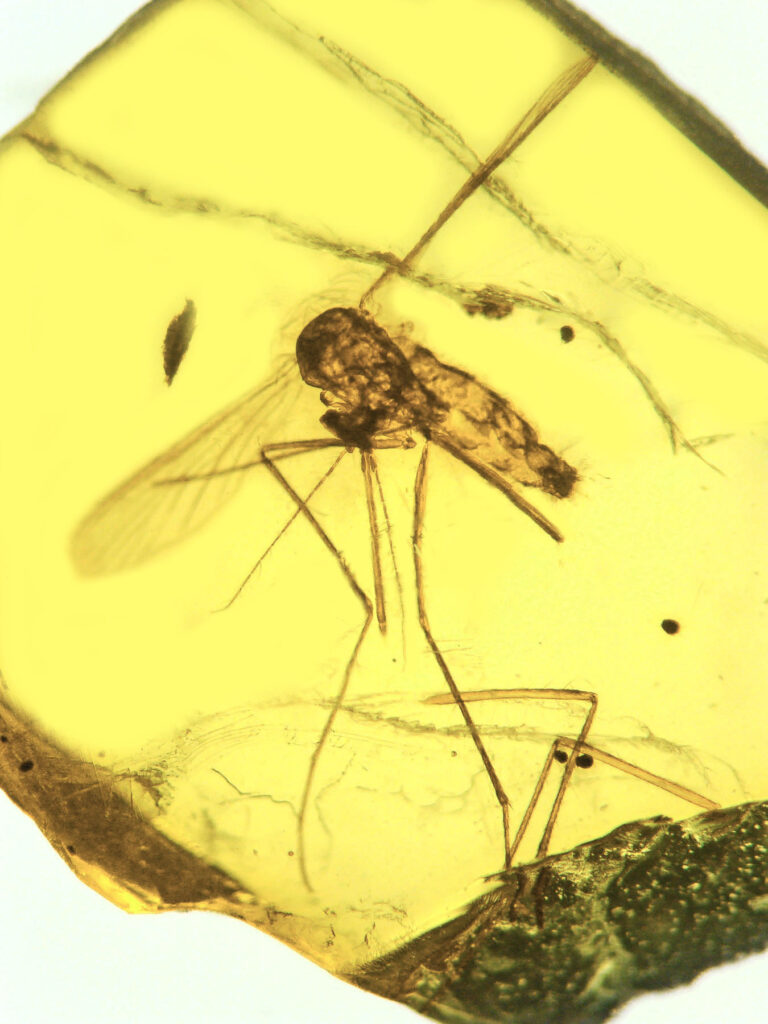

That’s the impression historian Timothy Winegard gives in his recent book, The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator. Winegard attempts quite the literary and historical feat: to summarize an entire history of the Western world showcasing the outsized influence of this genus of lethal bloodsuckers in fewer than 450 pages, an influence, he concludes, that has been staggering.

The Mosquito focuses predominantly on how the General (and her cousins) influenced conflicts throughout history, from those waged by the Romans to World War II. The numbers are astonishing: 35% of European Crusaders were killed by mosquitoes; 84% of the British force that invaded Cartagena in 1727 died of yellow fever; and 85% of Horatio Nelson’s troops in Nicaragua succumbed to dengue, yellow fever, and malaria in 1780. During the Spanish American War only 379 American servicemen were killed in combat, but 4,700 died of mosquito-borne disease. And the General doesn’t discriminate. Winegard’s list of the General’s casualties includes some of history’s most famous names—Oliver Cromwell, Augustine, Dante, Alexander the Great—alongside all the anonymous soldiers.

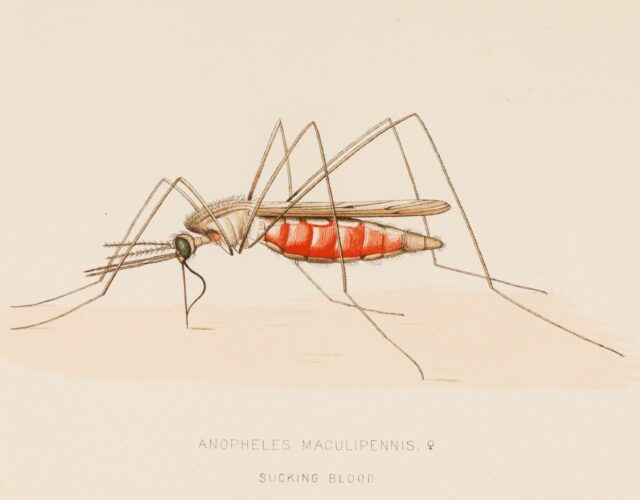

Only three mosquito genera out of 112 transmit human diseases. Anopheles mosquitoes are the only ones that carry malaria, though they also harbor filariasis (also called elephantiasis) and encephalitis. Culex mosquitoes carry encephalitis, filariasis, and the West Nile virus. Aedes mosquitoes carry yellow fever, dengue, and encephalitis. Only female mosquitoes bite since they need blood to produce their eggs; male mosquitoes survive just fine on nectar.

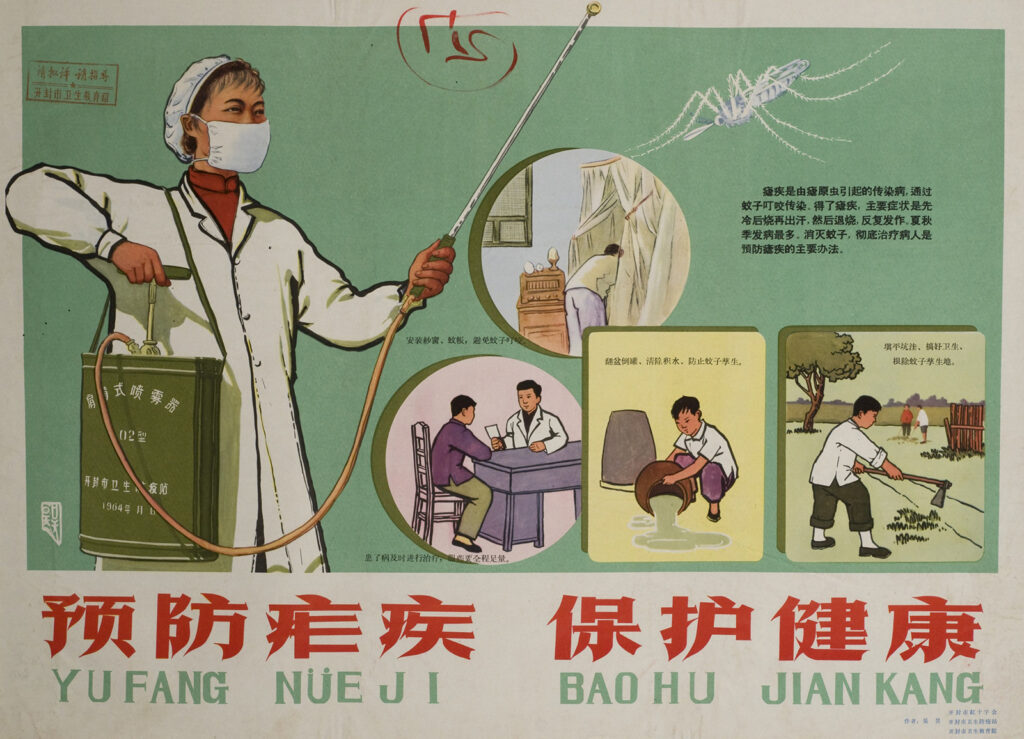

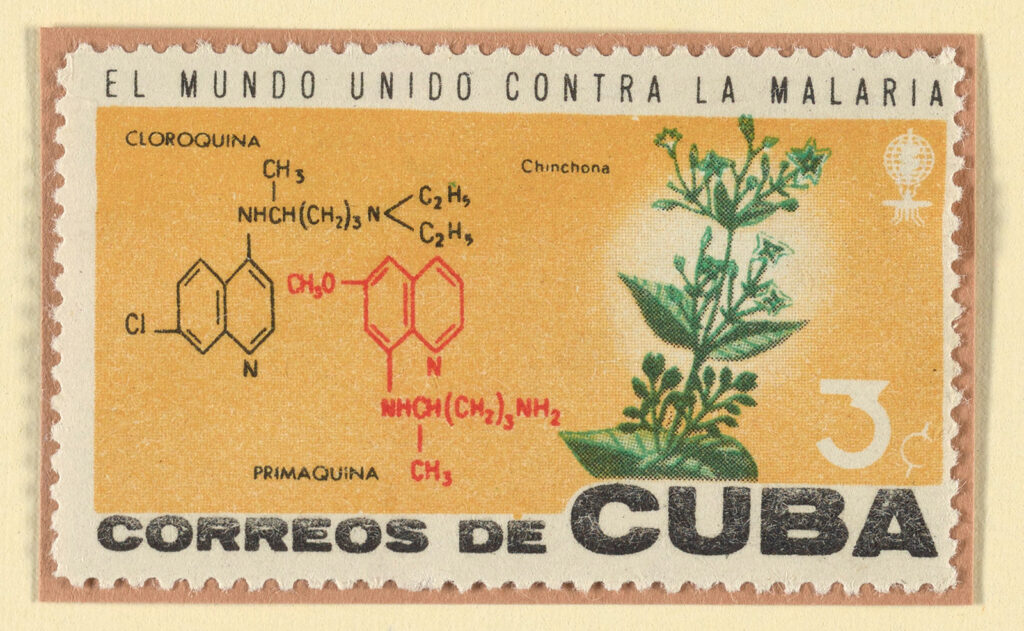

And that is about all the science that readers will receive in Winegard’s book, which focuses instead on the historical impact of mosquito-borne disease. The text provides little in the way of scientific explanations of malaria, its treatments, or the scientists who developed them. Winegard does include a very generous bibliography, so there are plenty of suggestions for readers wanting to know more.

Note too that this is a history of the Western world, with limited pages devoted to Africa or Asia. (We do get to South America but mostly during the time it’s being colonized by Europeans.) As such The Mosquito can’t claim to tell the definitive story of the mosquito, despite the rest of the book covering everything from ancient Sumer, where the first account of malaria was found engraved in a clay tablet, to DDT.

But back to the Nazi scheme to unleash mosquitoes on the Italians. Rome had long been protected from outside invasion by a large perimeter of swampland. “The marshes, often referred to as the Campagna, flanking the city of Rome were home to legions of lethal mosquitoes and were the defensive equivalent to armies of men,” writes Winegard. “Successive invading armies from the Punic Wars to the Second World War were literally swarmed to death.” Hannibal crossed the Alps but chose to bypass Rome. Visigoths, Huns, and Vandals were all turned back by disease. Romans too suffered from endemic and epidemic malaria.

Several rulers tried to do something about the lethal marshes: Julius Caesar, Napoleon, at least seven popes. (Pope Sixtus V contracted malaria during his marsh reclamation project and died in 1590. At least six other popes joined Sixtus in death by malaria.) Not until Benito Mussolini pushed through a massive, 10-year drainage project did the threat from the marshes cease. But when Allied forces started their march north through Italy, German eyes turned to the new drainage systems.

“In October 1943,” writes Winegard, “Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, or perhaps even Hitler himself, issued the order to purposefully regenerate mosquitoes and disease.” Kesselring’s orders were to proceed “with all the means at our disposal and with maximum harshness.” He proclaimed, “I will back any officer who in his choice and harshness of means goes beyond our customary limits.” The Nazis wanted to stop Allied troops and punish Italian civilians at the same time.

The first step was to confiscate all quinine supplies and mosquito netting from Italian homes and to slice open protective window screens. Next the Germans reversed the pumps draining the marshes and opened the dykes, refilling 90% of this former marshland with brackish water. Then they introduced millions of larvae of Anopheles labranchiae into the marshes and added land mines and other defensive obstacles. The German efforts were unintentionally aided by Italian veterans returning from the Balkan Front, who carried quinine-resistant strains of malaria ready to be spread by a new crop of winged assassins.

The Nazi strategy was ruthless, but the results were mixed. The British and American soldiers who made landfall just south of the marshes were given antimalarial drugs, allowing most to survive the biological attack. But the effect on the civilian population was severe. Officially reported malaria cases rose from 1,217 in 1943 to 54,929 in 1944, in a population of only 245,000. (Actual numbers were likely higher.) The two years following also saw rates of infection that were well above average. Only in 1950, after the marshes were again drained, did the imported mosquitoes finally and fully die out.One of the 45,000 American soldiers who got malaria during the campaign was Sergeant Walter “Rex” Raney, who happens to be Winegard’s grandfather-in-law.

“Those blasted mosquitoes were more relentless than the German shelling,” Raney remembers. “By the time those mosquito-spraying fellows came around and drenched us and everything else they could aim at with DDT . . . it was already too late for me.” But Raney’s experience with mosquitoes was about to get significantly worse.

Raney was part of the team that liberated Dachau in April 1945. One of the many horrors of Dachau was that it was home to the Nazi tropical medicine program. From 1942 to 1945 Claus Schilling experimented on more than a thousand camp prisoners as part of his research on malaria and synthetic antimalarial drugs, killing 300 to 400 of his subjects. Perhaps more ghastly, an entomologist on staff at Dachau, Eduard May, went as far as developing malaria-carrying mosquitoes that could be delivered by air as bioweapons, though he did not test his invention on prisoners. Raney contracted his second dose of wartime malaria from “an experimental Nazi mosquito,” as Winegard puts it, and this time the symptoms were so severe they ended his military career.

Despite new weapons to fight her, General Anopheles isn’t likely to stop her service anytime soon. “We’re still at war with the mosquito,” Winegard concludes. “History has shown her to be a dogged survivor. For now, the indefatigable mosquito remains our deadliest predator.”