One day in 1855 a boy known to history only as W. C. B. fell ill. His mother found him suffering from fever, wracked with body aches, and fatigued. Worried by these symptoms, she sent for the local apothecary, who arrived a short time later with a jar containing some brightly colored, slimy creatures. The mother heaved a sigh of relief; help had arrived in the form of a leech.

More than 50 years later W. C. B. submitted a letter to the popular British serial Notes and Queries about his childhood memories of being “leeched” on a regular basis. The bloodsuckers were placed “inside the nostrils, on the inside of the lower lip, on the chest, and on the side, sometimes by four at a time.” Such childhood experiences were not unusual. From the late-18th century through the 19th century a craze for leeching gripped Europe and North America and led to the collection, trade, and use of millions of leeches each year. The relationship between people and the medicinal leech, however, has a much deeper history.

Thousands of years ago physicians began exploiting the vampiric nature of these delicate relatives of the earthworm, transforming them into an important medical device that became part of a long-standing tradition of bloodletting. Use of the animals reached Europe in the Middle Ages through translation of medical texts from the ancient Greek and early Islamic worlds. Well into the 19th century European physicians relied on these texts for guidance in balancing the body’s four humors.

Bloodletting was thought to help balance the humors and was a common treatment for a variety of illnesses; it was even used as a general preventive. Belief in the merits of bloodletting grew stronger in the 18th and 19th centuries as newly emerging theories of disease expanded the practice’s application to nearly every ailment.

Yet bleeding with leeches was “troublesome and uncertain,” according to William Buchan’s widely read domestic-medicine manual. It was difficult to gauge how much blood was being taken, and blood often continued to flow after the leech was removed. Early editions of Buchan’s book, first published in 1769, were generally dismissive of leeches. Yet by the early 19th century Buchan’s health-care bible was eagerly pushing leeches for all sorts of problems. Have a fever? Try leeches. Tooth bothering you? Try leeches. Pregnant? Slap on a few leeches. Hemorrhoids got you down? You guessed it; grab yourself some leeches. Why did the use of medicinal leeches surge in popularity in the early 19th century after thousands of years of playing only a modest role? The answer involves medical theory, marketplace transitions, aquaculture, and the emergence of an international trade in pharmaceuticals.

The Medicine behind the Madness

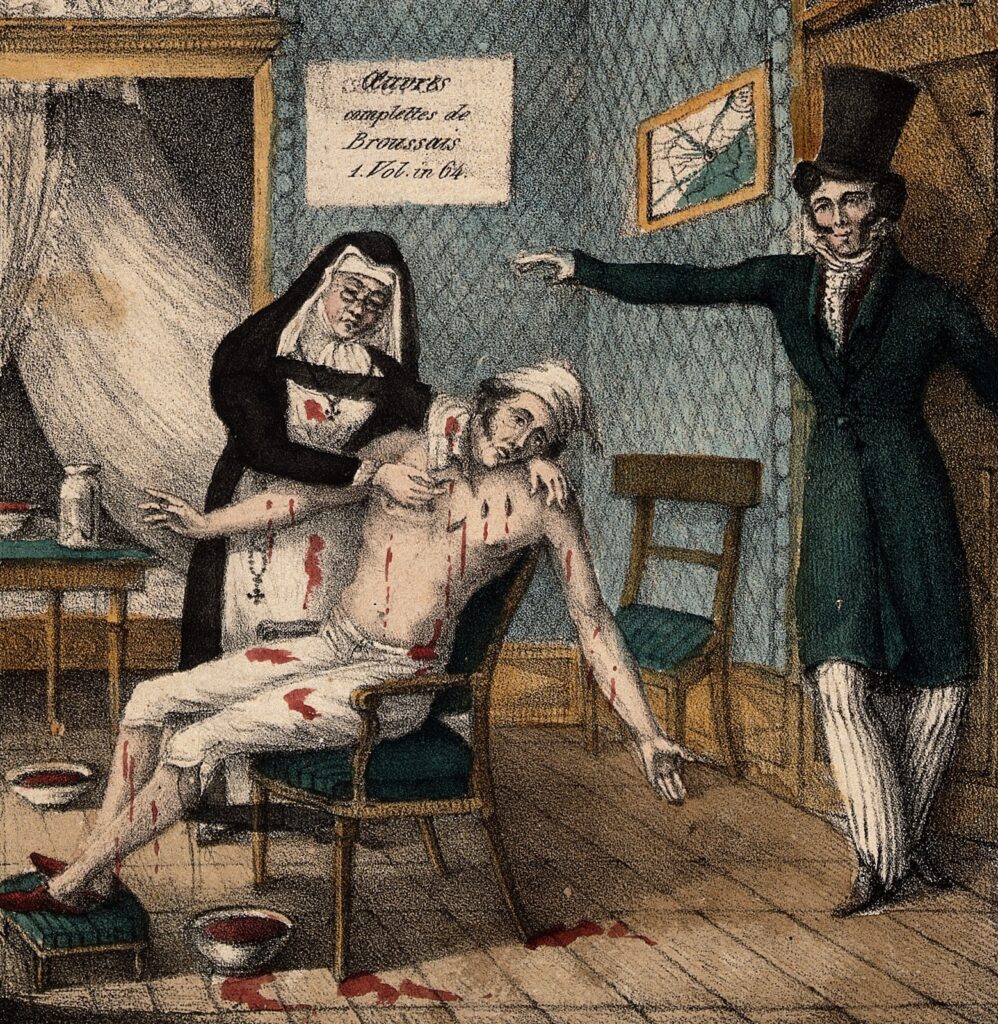

At least some of the popularity of leeching during this period can be traced to the theories of François-Joseph-Victor Broussais, a French physician who believed health and disease exist on opposite ends of a continuum. Broussais thought that when normal physiological processes go awry, inflammation takes hold, which in turn produces illness. Irritation in the gastrointestinal tract, Broussais argued, leads to inflammation that could cause illness anywhere in the body. If all diseases come from the same source, he reasoned, all treatments could be modeled on the same therapy: bloodletting, preferably with leeches.

Broussais was the chief physician at Val-de-Grâce military hospital in Paris, and he treated soldiers’ typhus, dysentery, and enteritis the same way—with leeches. Under Broussais the standard of care called for applying 30 leeches to each new patient, no matter the diagnosis.

This expansion of bloodletting to treat the wounded and very sick was a new phenomenon. There had long been objections to blood loss via lancet, an often traumatic, painful process. In contrast, many of Broussais’s followers came to see the leech as offering a kinder, gentler approach, inducing a “state of relaxation of the nervous energy of the body,” according to British surgeon Rees Price, author of A Treatise on the Utility of Sangui-Suction or Leech Bleeding (1822). The medicinal leech also opened up new sites of treatment. As W. C. B. later learned, leeches could access hard-to-reach and sensitive areas, such as the inside of the ears, nose, mouth, and other even more intimate spaces.

Broussais’s model of health and disease appealed to the public: it was easy to understand, fit within long-standing ideas about the benefits of bloodletting, and offered a simple, accessible treatment in the form of the leech. The leech craze spread quickly and soon transcended the borders of Paris and France. Driven in no small part by Broussais’s needs for a constant supply of leeches for his hospital, a lucrative transnational industry burgeoned, providing income for leech collectors and farmers, importers and exporters, apothecaries, quacks, and hucksters.

The transatlantic infatuation with the humble leech spilled over into the fashion and culture of the time, inspiring poems, leech-shaped embroidery patterns on dresses, and ornate leech jars that adorned the windows and counters of apothecary shops and the mantelpieces of the well-to-do. Large, white leech jars with blue and gold embellishments were so common, W. C. B. remembered, that they could “be seen on every druggist’s counter.”

Blood Work

While the Victorian bourgeoisie may have waxed poetic about the medicinal leech, the supply business was a dirty, difficult affair, one that hinged on access to shrinking wetland areas and required a willing supply of laborers to act as lures and collectors.

One of the earliest accounts of leech collecting comes from The Costume of Yorkshire, a collection of colored prints published in 1814. One bucolic image, titled Leech Finders, depicts three women wading through a shallow pond. One woman places a leech into a small barrel cradled in her arm, while in the background another casually holds a long stick to stir the leeches from their shallow hiding places. A third woman relaxes on the bank, her feet dangling in the water.

But the pastoral depiction of Leech Finders belies the scale of the leech trade during this time. At the height of the craze France alone imported 33 million leeches in a single year. Yet demand far outstripped supply. Overharvesting was a problem, but so was the drainage and development of land for agriculture, which reduced leech habitat. By the end of the 18th century medicinal leeches were nearly extinct in many countries, including Ireland, England, Wales, and the Netherlands. In response countries began farming leeches and importing wild ones from places as far away as Russia, Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire.

As wild populations dwindled, efforts to harvest local leeches grew more desperate. The scene captured by the Leech Finders was in marked contrast to how leech collectors were shown just a few decades later. In a clipping from the French medical publication Gazette des Hopitaux, its author describes a lonely, pale man collecting leeches, noting “his woebegone aspect, his hollow eyes, his livid lips, his singular gestures.” It would be understandable, the author adds, “to take him for a maniac.” English poet William Wordsworth captured a similar image of the vanishing leech collector:

To gather leeches, being old and poor:

Employment hazardous and wearisome!

And he had many hardships to endure:

From pond to pond he roamed, from moor to moor;

Housing, with God’s good help, by choice or chance;

And in this way he gained an honest maintenance.

When the narrator inquires further, the man laments the dwindling numbers of wild leeches:

But they have dwindled long by slow decay;

Yet still I persevere, and find them where I may.”

The rise of leech farms drove the last of these haunting figures from the landscape as more intensive breeding practices took hold. One account from the period reported that a leech breeder “who has four hectares of marshes, drives into them every year upwards of 200 cows and many dozens of donkeys for the nourishment of 800,000 leeches.” It would be several decades before pieces of liver and large nets completely replaced the bare legs of the peasantry and their livestock when it came time to harvest the creatures.

Yet these large operations created nearly as many problems as they set out to solve. Overcrowded and poorly oxygenated pools fostered disease, hindered breeding, and attracted predators. In one particularly devastating incident a flock of migrating ducks wiped out a farm’s stock of 20,000 leeches in a single day. Treatises often lamented that leeches were loath to reproduce in captivity; a lack of knowledge about their life cycle left even the most devoted leech keepers scratching their heads. As a result sustaining the practice of leeching hinged on keeping large shipments of imported leeches alive and healthy.

Theories for increasing leech longevity abounded. In The American Dispensary, for example, pharmacists are credited with observing that adding iron to the water in which a leech lived “prevented it from becoming putrid and rendered changing [it] unnecessary for longer periods.”

Doctor and naturalist James R. Johnson took great care in collecting information for his Treatise on the Medicinal Leech (1816), in which he argued that leech health required regular water changes and access to a bottom layer covered in what he called “turf” or “Marsh Horse-Tail.” The latter was crucial for giving the leech a “ready means of disencumbering itself” of its slimy outer coating, which, if not regularly scraped off, could “give rise to disease” among the animals.

Leech keeping came to rely on a system of craft knowledge and expertise in which the keepers re-created leeches’ natural habitats as closely as possible. Many patients, however, tossed “used” leeches back into the nearest local ditch or waterway. This use-and-lose practice may have saved the native populations from disappearing entirely, though today they remain endangered in several European countries.

Most troubling to physicians, leeches only needed a meal once every six months. That fact, combined with the hazards of leech keeping, drove inventors to develop mechanical substitutes that could mimic the creature’s ability to remove blood gently and be handled with greater control. The first such device is often credited to French doctor Jean-Baptiste Sarlandière, who in 1817 introduced a mechanical leech made of pumps, valves, and puncturing attachments. A simpler and much more popular cylindrical model invented a few decades later by another Frenchman, Charles Louis Heurteloup, consisted of only two parts, with the first making a small, circular incision and the second sucking up an ounce of blood. Three features made mechanical leeches more appealing for practitioners: they didn’t get sick or die, they always had room for more blood, and they were much easier to transport.

The Longevity of the Leech

As cholera spread across Europe and North America in the 1830s, Broussais, the French physician and bloodletting booster, touted leeches as the most appropriate response to the epidemic, and their use peaked. But leeches proved no match for the deadly cholera, and in the aftermath leech therapy began a long decline.

By the end of the 19th century most European physicians had turned away from use of leeches, though U.S. doctors, more fractured in discipline than their European counterparts, continued to draw on North America’s seemingly endless supply of the creatures. Well into the 1900s jars of leeches could be found in American bars and barber shops, where they were administered as first aid or to treat a swollen or blackened eye. They have remained a part of folk medicine in some communities in the United States and Europe to this day.

Yet over the past 50 years or so, the leech has wriggled its way back into mainstream medicine. Starting in the 1950s, surgeons developed techniques to reconnect the body’s tiny and delicate capillaries, reattaching severed limbs and even fingers, toes, and ears. Unfortunately, the blood’s tendency to clot and pool around the reattachment site often blocked the body’s own healing process. That’s when doctors turned once again to their old friend.

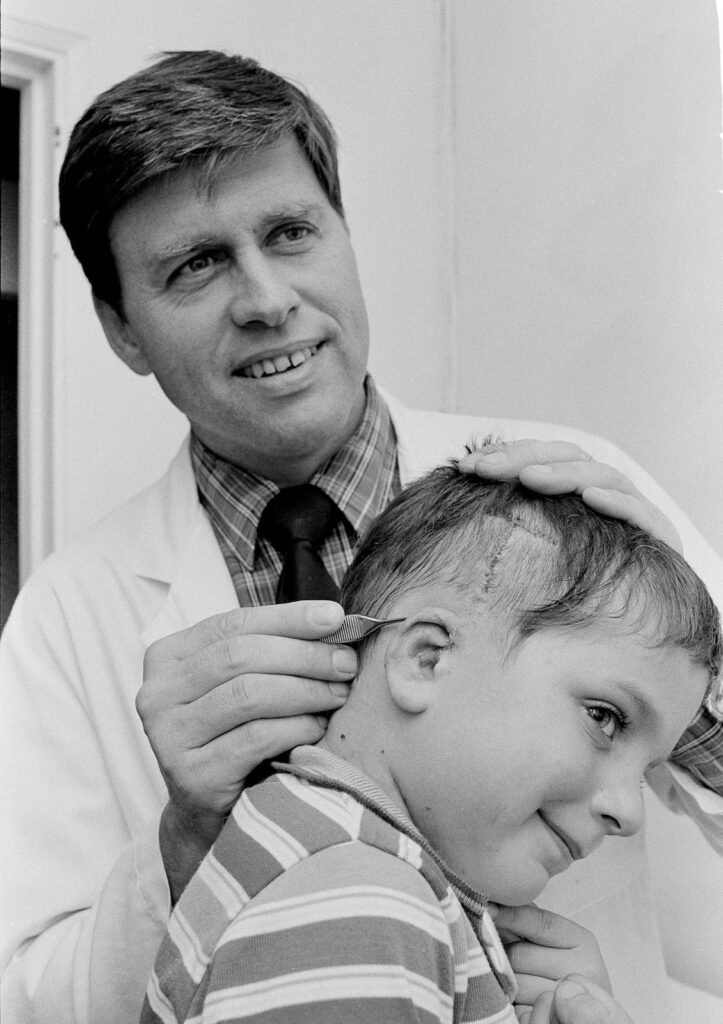

In 1985 leech therapy gained momentum after a particularly compelling case made headlines. An American plastic surgeon named Joseph Upton treated a five-year-old whose ear had been bitten off by a dog. Ears are notoriously difficult to reattach because they rely on tiny capillary connections. In this case the reattached ear began to fail, and it appeared the child would likely lose it entirely. Upton remembered reading about surgeons who had used leeches for microsurgeries and decided to order some of the critters. The leeching worked, and the child’s ear was saved, marking the second successful ear reattachment performed up to that point.

These days medicinal leeches are increasingly in demand. In 2004 the FDA approved the use of medicinal leeches in reconstructive and plastic surgery. By draining blood that has pooled, this “device” stimulates and encourages blood flow in damaged and reattached tissues. Some doctors now prescribe leeches for a host of other ailments, including varicose veins, neuropathy, blocked arteries, and even osteoarthritis.

But what makes leeches so effective? It comes down to saliva. Leech saliva contains a chemical called hirudin, a natural anticoagulant. In the 19th century Broussais believed that leeching, by reducing inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, treated most diseases. As it turns out, he was right—at least about the leech’s anti-inflammatory powers. Today’s proponents of the medicinal leech also point to the anticoagulants in leech saliva but add that inflammation is reduced only around the bite. As Ronnie Shammas, a surgery resident at Duke University Medical Center, put it, “While blood thinners might accomplish a similar goal, the result would be much less localized” and thus less safe for a patient.

Leeches’ newfound popularity has revived leech farming, now a small yet lucrative part of the modern pharmaceutical industry. In Wales, once a rich source of wild medicinal leeches, Swansea’s Biopharm company runs the world’s only leech supply operation. Raised by “leech-growth technicians,” this new generation of medicinal leeches lives in carefully monitored, high-tech tanks and dines on blood-filled sausages. The annual harvest of 60,000 leeches, though, pales in comparison to the hundreds of millions collected and used throughout the 19th century.