In the mid-1970s Lisa Lindahl fell in love with jogging. She was studying education at the University of Vermont when the new exercise craze swept through the country, and by the time she graduated in 1977, she was running 30 miles every week. For Lindahl jogging was a way to meditate while moving through nature. There was only one problem: running was painful for her in ways that men couldn’t understand.

“I was uncomfortable,” Lindahl said in a 2016 interview for the Distillations podcast. “Really, I have to say that I loved running, but my upper torso and my breasts were not comfortable.”

She tried everything from binding herself with an elastic bandage to going entirely braless, which drew harassment from passing drivers. She finally settled on a regular bra that was one size too small. It helped with the bouncing, but she still couldn’t run long distances without getting chafed.

One day Lindahl’s sister called and mentioned she had just started jogging. She commented on how painful running could be, and Lindahl told her about the small-bra technique. Her sister jokingly asked, “Well, why isn’t there a jockstrap for women?” Lindahl laughed, but after she hung up she considered the question seriously. Why wasn’t there a jockstrap for women?

The answer to this question, it turns out, reveals a lot about women’s role in athletics and society as a whole. Throughout history women as a group have had less opportunity than men to travel, to learn, to earn a living, and to compete. And time and again women have circumvented these and other obstacles—sometimes through the law, sometimes through ingenuity, and sometimes through technology.

Easily forgotten among the marvels and novelties of the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition is the first internationally sanctioned bicycle race. No fewer than 8,000 spectators crowded around a nearby track to cheer American cyclist Arthur Zimmerman to two gold medals in the three-event competition. The cycling race, which included participants from as far off as South Africa, was covered by newspapers across the nation. This prominence was symptomatic of the larger bicycle craze that had broken out around the country since the introduction of chain-driven safety bikes in the 1880s. By the 1890s Americans everywhere were pedaling about.

Cycling was a hobby for some, but for couriers who delivered messages and packages, bikes were an indispensable tool. These couriers, mostly adolescent boys, formed a subculture supported by a network of skilled bicycle mechanics and machinists that changed the shape of cities: before there was the corner gas station and car-repair shop, there was the bike shop. The streets themselves, however, remained mostly unchanged. Bike couriers had to ride over roads made of uneven stones, wood, and dirt. Jostled atop wooden wheels and hard leather saddles, bike couriers could have easily sympathized with Lindahl’s jogging pain.

In 1897 Charles F. Bennett, a former employee at a Chicago sporting-goods company, patented an invention that addressed the couriers’ problem. His solution was an undergarment that used compression and elastic to protect male genitalia, basically a white waistband and pair of leg straps attached to a front pouch, which he marketed as the Bike Jockey Strap. Within a few years Bennett’s undergarment had found a home in all kinds of organized sports, and dozens of companies started emulating his athletic supporter. His invention was colloquially named the “jockstrap,” and athletes who wore them eventually became “jocks.”

Meanwhile, women had their own set of problems, still saddled with the Victorian era’s torso-strangling corsets—at least those who could afford the garments. British tennis player Charlotte “Lottie” Dod, the daughter of a wealthy cotton trader, was such a person. At age 15 Dod won the 1887 championship at Wimbledon while wearing a stiff, sharp corset. After the match she returned to her dressing room and found that her undergarments were soaked in her own blood. The metal and whalebone of her corset had punctured her skin as she ran and lunged for the ball.

Unfortunately for Dod, who quit competitive tennis in 1893, her playing days ended just as designers started piecing together the elements of the modern brassiere. Early bras were relatively simple, often two soft cups of cloth with bands that tied around the back, but they were more comfortable and formfitting than anything that had come before. Wearing a bra, which to Lindahl felt like torture while jogging, was a relief to women at the turn of the 20th century. But as authors Jane Farrell-Beck and Colleen Gau explain in Uplift: The Bra in America, while early brassieres were certainly easier to move around in than corsets, bras did not fully supplant the much more constricting corset until the perception of what was fashionable shifted and manufacturers caught on to the trend.

As with the jockstrap, this shift in wardrobe was brought about in part by the bicycle.

Bicycles allowed women a freedom of movement they had rarely enjoyed. No longer so reliant on men to get around, this “New Woman” (a feminist ideal invented by Irish writer Sarah Grand) had greater opportunity to work and socialize outside the home, and even organize and agitate for her social and political rights. Susan B. Anthony remarked in 1896 that cycling had “done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world: it gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance.”

The new mode of freedom demanded less restrictive apparel. Women began to adopt more practical fashions—bloomers, short haircuts, and brassieres—advocated by long-standing activist groups, such as the National Dress Reform Association.

“Clothing for sports engaged a wide variety of women in a discussion about their relationship with their garments,” writes historian Sarah Gordon. “At a time when mainstream women rarely challenged fashion’s dictates, the novelty of sports offered an opportunity to rethink women’s clothing.”

The knee-length bloomers and baggy pantaloons worn by female cyclists at the turn of the century became emblematic of this newfound autonomy. Since then women’s rights and women’s fashion have often been symbolically joined. Dressed with stylish elegance, the Gibson Girl was defined by her self-possession and independence. Jazz Age flappers took this attitude even further; the short hair and short skirts they wore flaunted their rejection of traditional gender norms. A couple of generations later the bra, once a symbol of liberation, briefly became emblematic of male oppression. In the 1960s and 1970s many women stopped wearing them altogether, and some even made a point of trashing them in public to demonstrate their repudiation of an article of clothing commercialized and sexualized by men.

The women’s liberation movement declared that the personal was political and demanded equality for women both in the workplace and in their personal lives. A series of legal decisions in the 1960s and 1970s established women’s reproductive and economic rights, while Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972 forbade gender discrimination in the workplace and in schools that take federal dollars.

Lindahl graduated college in 1977 amid this climate of female independence and was among the first generation of women to feel the effects of Title IX’s directives. The summer after graduation she simultaneously worked for a rehab center, designed and sold stained-glass artwork, took graduate courses at night, and whenever she could fit it in, jogged.

Joining Lindahl and her husband that summer was an old friend, Polly Smith, who rented a room from the couple while in town to design costumes for a local Shakespeare festival. Lindahl decided to put her friend’s skills to work in solving her jogging problem.

Together Lindahl and Smith came up with a list of qualities a running bra would need: stable straps that wouldn’t fall off; no metal or plastic that could dig into the skin; breathable fabric that would wick away sweat; and enough compression to prevent excessive movement.

But none of their experiments worked much better than a smaller bra. During one particularly frustrating day Lindahl’s husband walked into the room where the pair were working, pulled a jockstrap over his head and onto his chest, and said, “Hey, ladies, here’s your jock bra.”

The dumb joke was an epiphany for Lindahl. “I took it from him, and I pulled it over my chest and had this ‘ah-ha’ moment,” she remembered. “I looked at Polly and said, ‘You know what? This could solve our engineering problems.’ ”

Smith sewed two jockstraps together, creating a crude brassiere with two pouches, and tried it on. The elastic wound around her back in an X shape that held the undergarment together better than anything they had tried before. But the fabric itself was rough and itchy, so Lindahl asked Smith to find a better material.

Smith settled on Lycra, the 1950s-era DuPont polymer, blended with cotton. Thin strands of the two materials were woven together to give the fabric enough strength to hold its form while still being flexible. Lindahl and Smith used the material to re-create the shape of their double-jockstrap prototype and found it met their requirements. It was breathable, it controlled breast movement with compression, and there were no sharp hooks or clasps because the whole thing slid on over the head. Lindahl could finally jog with comfort.

But while one problem seemed to be solved, others were coming to the forefront of Lindahl’s life. She remembered that time in a 2015 blog post:

Lindahl didn’t know the first thing about starting a business, but she hoped that latent demand for her “jock bra” would make up for her lack of retail acumen. “I was enthusiastic, already marketing in my head—thinking of a new kind of business, a new way of business, a women’s business,” she remembered in her blog.

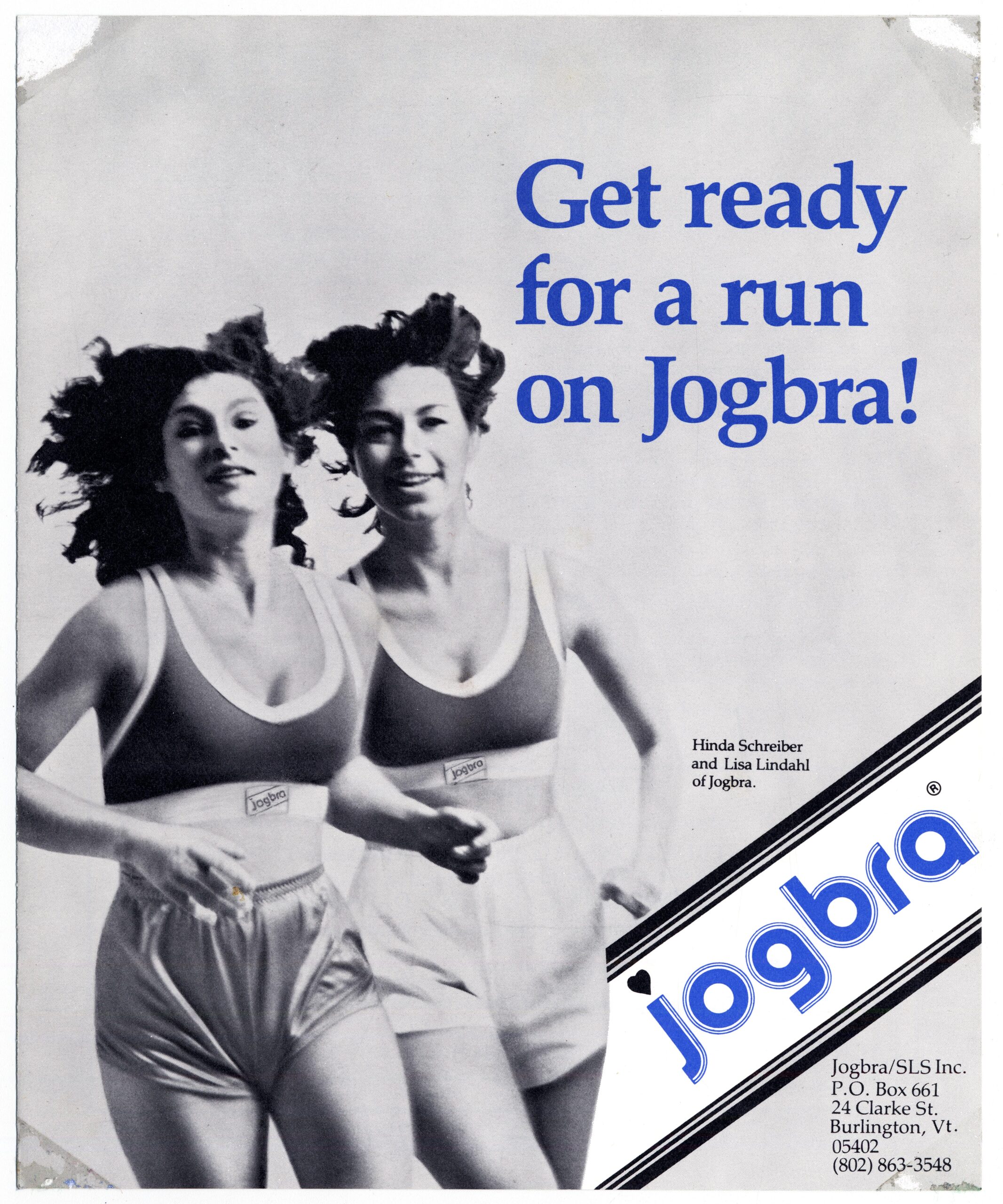

Smith had no interest in the business, so Lindahl moved forward with a mutual friend, Hinda Schreiber, who struck a deal with a cut-and-sew company in South Carolina. Once the company had produced a few dozen sample bras, Lindahl bought an ad in Running Times and started cold-calling sporting-goods stores.

“I had never sold anything in my life,” she said in her Distillations podcast interview. “I’m walking in there with my little suitcase full of bras saying, ‘Would you carry this bra in your store?’ They’d go, ‘What? This is a sporting-goods store. I’m not going to carry a bra.’ I’d look at them and say, ‘You sell jockstraps, don’t you?’ They’d go, ‘Ohh.’ ”

Lindahl’s clever sales tactics persuaded a handful of stores in the Northeast to carry her jock bras. Soon she hired sales representatives all across the country and was surprised when she was later advised to slow down. With such a rapid expansion of operations, friends and advisers warned, the company could collapse if the demand for her bras didn’t keep growing. Luckily, it did.

“We were profitable our first full year in business and didn’t even know that that was unusual,” she said.

Lindahl was also advised to rethink the name of her invention. Genteel Southern women, she remembered, were turned off by a name that conjured images of male genitalia. Eventually she relented and renamed it the Jogbra.

By the 1980s, many other sports-apparel and lingerie companies were producing different versions of the Jogbra that were geared toward all kinds of exercise, including the glitzy Jazzercise craze. Within a few years most female athletes were wearing a sports bra. But while women around the world were embracing the sports bra, Lindahl was letting go. In 1990 she sold her company to undergarment behemoth Playtex.

The Jogbra wasn’t just a commercial success; it also became a new kind of feminist symbol, cemented by one athlete and one moment in particular.

It was a broiling hot July afternoon in Pasadena, California, when the United States faced China at the Rose Bowl in the finals of the 1999 Women’s World Cup. The players battled relentlessly, but at the end of full time the game was stalled at 0–0. Overtime didn’t produce a goal either, so the championship came down to a best-of-five penalty kick shoot-out.

China went first, successfully sending the ball past American goalkeeper Briana Scurry; the U.S. team answered, and the teams traded goals again in the second round. But in the third round Scurry charged forward and lunged to her left to deflect the Chinese attempt. The United States had its opening, and a soft shot to the upper-left corner put the Americans ahead. After trading goals again in the fourth round, China scored to open the fifth. The final shot, which could decide the game, went to U.S. defender Brandi Chastain. She carefully lined up her kick and then blasted the ball cleanly into the right-hand corner of the net. Overcome with joy, she ripped off her jersey and threw her hands into the air, revealing her sports bra to millions of spectators. Male soccer players had been celebrating victory in the exact same way for decades, but Chastain’s gesture kicked off controversy.

Chastain says she wasn’t trying to make a statement, but it’s hard not to interpret that moment of jubilation as a turning point that changed attitudes toward women in sports. The U.S. win and the media attention directed at Chastain and her team were followed by a surge in girls signing up to play soccer in the United States. According to U.S. Youth Soccer, there was a 45% growth in the number of high-school girls signing up to play soccer between 1998 and 2014 compared with a 30% growth among boys.

While it’s impossible to truly measure the effects of Chastain’s celebration, its influence has been lasting and far reaching. Playwright Sarah DeLappe claims that her experience as a nine-year-old watching Chastain win the World Cup inspired her to write The Wolves, a coming-of-age play about a female soccer team, which opened to critical acclaim in summer 2016.

As for Lindahl, she says her contribution to female independence was merely a happy accident. She designed comfortable jogging equipment for herself that happened to catch on with others.

“It’s just something I wanted, so I made it,” she said. “Now, all these years later, my eyes are big, wide. Like, ‘Wow. This really had a big impact for women. Who knew?’ ”

Whatever Lindahl’s intention, her creation has become a permanent part of sports and history. Early prototypes now reside in the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As for the jockstrap that inspired Lindahl’s Jogbra? It’s lying in a heap of dirty laundry on the locker-room floor of history.