The place: Suburbia, Anytown, U.S.A.

The time: Late 1950s.

The scene: A room in a house with a table set for dinner. A family of four is sitting down to a meal of meat, potatoes, green beans, bread, and salad.

Mother: “Don’t forget your vitamins!”

[A small apothecary-style bottle sitting next to the salt and pepper shakers is now passed around. Each family member removes the stopper, takes out a little green pill, and washes it down with a glass of milk.]

Fifty years before this dinnertime scene vitamins existed only as an idea without a name in the minds of a few biochemists investigating human nutrition. They postulated a mysterious substance, something beside fats, carbohydrates, proteins, and salts, existing in foods and essential to health. What they discovered gave birth to an industry and a highly marketable product—the vitamin pill.

Vitamin pills came of age in a country preoccupied with economic depression and war, and grew with a return to prosperity and subsequent consumer-oriented culture. Yet that neat, brightly colored tablet could not have appeared without the rise of the lab rat and an expanding and scientifically sophisticated pharmaceutical industry. Some welcomed the vitamin as a benefit to human health. Others considered vitamins to be little more than a fraud perpetrated on a gullible public. In either case, by the late 1950s the vitamin pill, attractively packaged and increasingly familiar, began to join salt and pepper at the table. Vitamins were here to stay.

Learning the ABCs

The word vitamine first appeared in print in 1912 in an article by Polish-born biochemist Casimir Funk. At the time Funk was at London’s Lister Institute working on the problem of beriberi, a disease endemic to mostly Asian populations who subsisted on diets of polished white rice. Funk came to the conclusion that the disease was caused by the absence of an essential nutrient in the rice rather than by the presence of a toxin, as earlier believed. He coined the term vitamine for this substance and proposed that similar essential vitamines could prevent such diseases as pellagra, scurvy, and rickets, whose symptoms included, respectively, sores and delusions, fatigue and bleeding gums, and bone deformations. Funk’s work was widely read and helped promote a powerful new idea emerging from the research of several scientists: that of deficiency diseases, which could be prevented and even cured by mysterious substances found in foods.

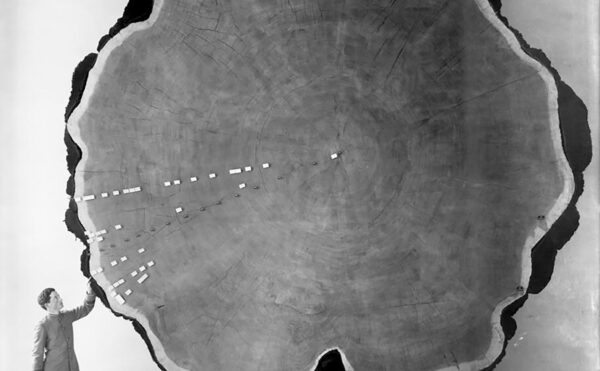

At the University of Wisconsin’s School of Agriculture, Elmer Vernon McCollum was investigating the nutritional needs of dairy cattle and decided to use rats as stand-ins for his cows. At the time rats were considered pests to be exterminated, not important lab animals. But they quickly proved essential to nutrition science, and use of rat colonies spread to other academic institutions as well as commercial labs. In 1913 McCollum, with the help of his rats, identified the first vitamin, a substance found in butter and egg yolk, which he dubbed “fat-soluble factor A.” Working with his colleague Marguerite Davis, he fed rats highly controlled diets that differed only in the quality of fat they contained. The rats fed with elements of butter fat or egg yolks thrived, while those on diets with fat derived from lard or olive oil failed to grow and eventually died. Though the chemical nature of fat-soluble A remained unknown, McCollum and Davis were able to transfer it from butterfat to olive oil.

Water-soluble B was the name given to the anti-beriberi vitamin that Funk found in the husks left behind after rice polishing; the substance discovered in citrus fruits, which were known to prevent scurvy, was called water-soluble C. A second fat-soluble substance was recognized by McCollum and his associate Nina Simmonds in the early 1920s and became vitamin D, the anti-ricketic. By this time the final “e” in vitamine had been dropped and the alphabet naming convention firmly established.

The new science of nutrition quickly permeated the national consciousness. Newspaper and magazine health columnists, government agencies, and home economists all spread the word about vitamins and the foods necessary to a good diet. Although research in vitamins began with the study of severe deficiencies, popular nutrition information focused on general dietary guidelines for health and vitality. This information was aimed at women, who had the primary responsibility for buying and preparing food, and it firmly linked specific food groups to essential nutrients. At the same time, images of laboratory animals started to appear in print, demonstrating the physical effects of severe vitamin deficiencies. Deformed, underweight, and sickly vitamin-deprived “after” rats (as well as other small experimental animals, including chicks, guinea pigs, and pigeons) were juxtaposed against pictures of their healthy, well-fed, “before” selves. Their striking recovery after returning to a balanced diet seemed almost miraculous.

“Vitamins for Pep!”

In 1920 Parke, Davis and Company launched Metagen, a five-grain (325 mg) capsule of “Concentrated Vitamine Extracts,” purportedly containing all the then-known vitamins—fat-soluble A, water-soluble B, and water-soluble C. Reporting on the new preparation, the Western Medical Times set forth a rationale for multivitamins that continues to resonate today: “This is the age of canned foods, polished rice, artificial butter [margarine], condensed milk, white flour and other refinements of our twentieth-century civilization, all of which make for convenience, perhaps, but their general use presents a problem in nutrition.”

Parke-Davis was an established pharmaceutical firm with its own research laboratory and scientists. Products like Metagen, intended to be prescribed by a doctor, were advertised to the medical profession. But other vitamin products also appeared, produced by patent or proprietary medicine makers who pitched the pills directly to the consumer. These manufacturers, who were often just businessmen, were not beholden to the ethical guidelines of the American Medical Association (AMA), which allowed drugs to be advertised only to doctors.

Promises of improved health and vitality aimed directly at the public created a great demand for vitamin preparations. One product, Mastin’s Vitamon Tablets, contained all three known vitamins along with iron, calcium, and phosphorus, making it perhaps the first multiple vitamin-and-mineral tablet on the market. Its proprietor, Francis B. Mastin, was an energetic advertiser who reportedly turned his product into a $1 million-a-month business in less than a year. Advertisements and testimonials promised Vitamon would “improve the appetite, aid indigestion, correct constipation, clear the skin, and increase energy.” Ad copy particularly emphasized the message “Vitamins for Pep!” an association that would stick with vitamin supplements for decades to come.

The AMA and federal food and drug regulators did not support the sale of these commercial vitamins. Consumers were seen as easily duped into buying worthless, perhaps even harmful, products. Regulators had difficulty deciding where vitamins fit in: were they a food or a drug? In addition the medical profession felt threatened by decision making that bypassed its authority. Some nutrition scientists and educators like McCollum were adamant in their disapproval of vitamin supplements, believing that vitamin needs were best provided through a balanced diet of wholesome foods. Although regulators eventually succeeded in instituting some labeling requirements and prosecuting the most exaggerated claims, vitamins and other dietary substances have remained part of a relatively open market in which decisions are left to the consumer.

The first vitamin pill to obtain the approval of the AMA was Oscodal, a sugar-coated tablet of vitamin A and D made from cod-liver oil using a process developed by Funk in the early 1920s. At the time, technical difficulties and the expense of extracting other vitamins from natural sources made them an inefficient proposition. That situation changed as pharmaceutical companies further developed their own research facilities and forged ties with academic laboratories. By the eve of World War II the pharmaceutical industry had learned to synthesize vitamins on an industrial scale; production was measured by the ton, and the country was poised to supply the nutritional needs of the entire world.

Are We Well Fed?

In 1941 President Franklin D. Roosevelt summoned the National Nutrition Conference for Defense to address the inadequacies of the American diet. “In recent years,” he wrote, “scientists have made outstanding discoveries as to the amounts and kinds of foods needed for maximum health and vigor. Yet every survey of nutrition, by whatever methods conducted, showed that here in the United States undernourishment is widespread and serious.”

The studies leading to this dire conclusion were based on surveys of family eating and spending habits carried out by government agencies in the mid-1930s. By then the nutrient content of various foods was known. Early 1941 saw the first table of recommended dietary allowances (RDAs), which included the daily requirements for six vitamins and two minerals, expressed in milligrams and international units. With these tools in hand the American diet was scrutinized and found to be lacking.

The Bureau of Home Economics, in the publication Are We Well Fed?: A Report on the Diets of Families in the U.S., concluded that only one-fourth of families in the United States enjoyed a diet that could be classified as “good.”A diet qualified as good if it exceeded by 50% the minimum requirements set for all seven nutrients studied—protein, iron, calcium, and the four vitamins. These calculations were based on a mixture of animal and human studies. For example, rats were used in controlled feeding experiments to measure vitamin A in test foods, while human needs for vitamin A were based on studies of people that measured the amount of the vitamin necessary to prevent night blindness, one of the first recognizable signs of deficiency. Scientists used the results from a handful of human subjects and the rat-based assays to determine the quantity of food, such as milk, eggs, and leafy greens, required to meet the vitamin needs of people.

Nutritionists adjusted recommendations further to account for the differing needs of infants, children, teens, pregnant and nursing women, and sedentary and active occupations. Behind the misleading simplification that 45,000,000 Americans faced vitamin starvation, however, lay the legitimate concerns of the Depression-era country: families with lower incomes had poorer diets in general, as did those who lived in towns and cities, away from farms’ ready supply of milk, eggs, and vegetables.

The National Nutrition Conference attendees were alarmed by the “inert calories” in the American diet, particularly in the forms of white bread and sugar. Modern flour refining had stripped bread of its natural vitamins and minerals, which in turn was stripping Americans of the strength they needed. As an immediate solution the conference gave its support to “enrichment” programs intended to restore certain foods to their “natural” (preprocessing) levels of nutrients. Flour enrichment had begun in the late 1930s as the B vitamins (thiamine and niacin) became available in bulk through industrial synthesis. But now, with national attention focused on the inadequacies of the American diet, progress accelerated, and the enrichment of flour and bread was largely accomplished through the voluntary cooperation of the milling industry, even before the War Food Administration mandated it in 1943.

Bread was not the first vitamin-enhanced product on the market. Vitamin D–fortified milk was introduced in the early 1930s, although fortification was accomplished mostly through irradiating milk with ultraviolet light rather than through the addition of bulk vitamins. Other fortified products appeared, such as Kellogg’s Pep, a breakfast cereal with added vitamins D and B1 that was introduced in 1938. New technologies allowed vitamins to be sprayed onto foods, such as the processed flakes that Americans ate for breakfast. The federal government, though, clearly distinguished between “enrichment,” which restored nutrients lost in processing, and “fortification,” in which vitamins could be added willy-nilly to almost any product.

Vimms and Vigor

By the early 1940s many vitamins were available in bulk at a fraction of the cost of a few years earlier, and proprietary commercial vitamins flourished. The cost of thiamine (B1), for example, dropped from $300 per gram in 1935, when it was first produced from natural sources; to $7.50 per gram in 1937, when it was synthesized; to 53 cents per gram in 1942.

The B vitamins in particular became the focus of vitamin anxiety and promise. Although B was one of the first vitamins recognized, it was little understood until the mid-1930s, when numerous components, including thiamine, niacin, riboflavin, B6, and calcium pentothenate, were isolated and synthesized. Studies of subclinical vitamin-B deficiency were vague and alarming: symptoms included fatigue and irritability, loss of appetite, nervousness, and even grey hair. Rumors spread that Hitler’s conquering forces induced vitamin-B deficiency in order to create dispirited, despondent populations. The “morale vitamin,” as it came to be called, seemed especially crucial to the well-being of the nation. Fortunately it was being pumped by the ton into breads and flour, and distributed in millions of vitamin pills with names like Vimms, Stams, and Benefax.

Advertisers made energetic promises for their vitamins. Vimms Vitamin Show, with Frank Sinatra, was popular on CBS radio, while advertisements for Stams (from Standard Brands) were heard on NBC’s Charlie McCarthy Show. “Take a minute, see what’s in it” ran one Vimms radio ad. “Make sure you get all the vitamins recommended by government experts.” Advertising in popular national magazines emphasized the B-complex vitamins as natural restorers of pep and vitality. Lists of the essential nutrients in multiple-vitamin formulations were advertised as the public grew more versed in vitamin science. Stams included five vitamins of the B complex, along with vitamins A, C, and D, and nine minerals, for an astounding seventeen ingredients. Manufacturers could boast that they met all the government’s minimum requirements for vitamins and often invoked the findings of “government experts and doctors” that revealed that three out of every four people suffered from “vitamin famine.” Celebrity endorsements were also part of marketing strategy. Paramount Picture stars like Betty Hutton (“I’m Hep to Pep!”) and Veronica Lake (“Preserve Your Verve!”) apparently owed their sparkle to Bexel B-complex vitamins.

Another vitamin product launched during these years remains one of the most successful brands today. As its name implied, One-A-Day was a once-daily vitamin pill, unlike Vimms and Stams, both of which required several pills each day. The multivitamin included A, C, D, and three Bs, but no minerals, resulting in a formulation that could fit in a single pill.

On the Table

World War II came to an end, but America’s desire for vitamins went on. The pharmaceutical industry emerged from the war strengthened by wartime production and government support for other new products, including antibiotics and vaccines. In 1946 the major vitamin producers formed the National Vitamin Foundation to finance vitamin research in academic laboratories. Educational materials produced by the foundation’s Vitamin Information Bureau continually reminded consumers of the necessity of vitamin supplementation.

With the addition of vitamin B12 in 1955 the multivitamin pill was nearly complete, but a few improvements were still in order before the pill was fully formed. New films and coatings wrapped tablets in pleasing colors. Abbott Laboratories, makers of Dayalets, created Filmtab, an ultra-thin, taste-inhibiting coating for tablets that replaced earlier sugar-coating techniques. Packaging design and point-of-sales displays also became increasingly important to marketing strategies. Products competed for consumers’ attention on store shelves and TV screens, and a new breed of ad men mined the psychological forces, fears, and desires that drew consumer to product.

In the late 1950s, when a number of vitamin producers marketed their pills in imitation apothecary-style bottles, vitamins were figuratively “dressed” for dinner. The bottle’s antique charm blended well with the traditional forms that still dominated the American home. At the same time, the apothecary bottle, a recognizable symbol of pharmacies, lent respectability to the product within. Possibly no housewife actually felt proud, as one advertiser suggested, to have the bottle on her dinner table next to the matching salt and pepper shakers; but neither did she feel it a personal indictment of the meal she had prepared. Salt and pepper shakers did not suggest a lack of flavor in the food, nor did the bottle of vitamins suggest a lack of the nutrients necessary to keep the family healthy. The pills were a reassuring nutritional safety net because, as one vitamin ad stated, “We usually eat what we like instead of what’s good for us.”

Acceptance in the American home did not mean the vitamin pill had achieved legitimacy in the eyes of many health professionals and government regulators. At the National Congress on Medical Quackery, called in 1961 to draw attention to the continuing problem of health fraud, the Food and Drug Administration commissioner told his audience that the most widespread and expensive form of quackery was the promotion of vitamins and dietary supplements.

The daily vitamin pill continues to have a strong hold on us, even as numerous studies throw doubt on whether ingestion of such supplements does any good. Surveys in 2003 to 2006 indicate that over one-half of all Americans take some kind of dietary supplement, of which the most popular are multivitamins and minerals. The science remains inconclusive, based as it is on the complexities and limitations of human and animal studies. The 2006 National Institutes of Health report stated that evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against daily supplementation. As consumers, we are left to decide for ourselves, and many will opt for the reassurance of the vitamin pill, recognizing as we do so that we are subject to the manipulations and exaggerations of advertising. After nearly 100 years of development, the vitamin pill, born of scientific discovery, perfected by industry, and shaped by Madison Avenue, shows no sign of going away.