Melanie Keene. Science in Wonderland: The Scientific Fairy Tales of Victorian Britain. Oxford University Press, 2015. 256 pp. $29.95.

Victorians, whom we remember today as uptight and proper, had a peculiar obsession with fairies. The little sprites were everywhere: art, music, literature, decorations. Gilbert and Sullivan opened their “New and Original Fairy Opera,” Iolanthe, in 1885. But for many people fairies were more than just a story: they were real, living, breathing creatures. Anthropologists wondered if lost tribes of fairies existed in unexplored regions of the world. Were fairies in the fossil record? Even the creator of Sherlock Holmes, the great Arthur Conan Doyle, went to his grave believing in the realness of fairies. In Doyle’s case “proof” lay in a series of photographs of fairies taken by two young girls. Fairies were serious business in Victorian Britain.

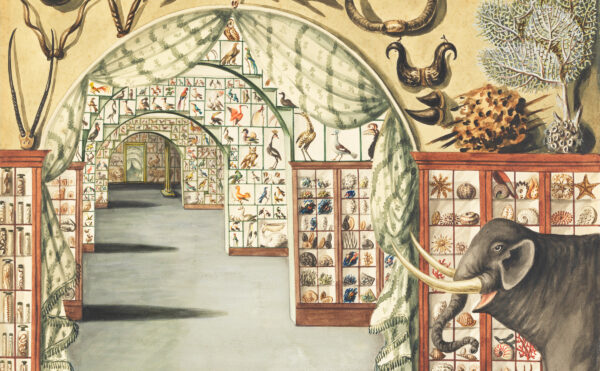

Children’s literature of this time, including books on science, was filled with mythological creatures. The inclusion of fantasy in science books was more than a ploy to get kids’ attention: it was a legitimate attempt to combine education and entertainment. “Fairies and imps, dragons and demons, giants and gnomes, appeared throughout these texts as framing devices, as storytellers, as starring characters, as illustrations, as the invisible forces of nature,” writes historian of science Melanie Keene in her new book, Science in Wonderland.

To explain their world, Victorians married the natural with the supernatural.

Lucy Rider Meyer’s Real Fairy Folks illustrated chemical concepts through fantastical text and beautiful line drawings. An oxygen fairy holding the hands of two hydrogen fairies, for example, represented a water molecule, the familiar H2O. If the fairies were flying around with a lot of energy, they were gases. Cold, still, and huddled together? They were solids. Other fairies making an appearance in the literature of the time include the Amber Spirit of electricity, who sped along the transatlantic telegraph cable, and Fairy-Know-A-Bit, who put human clothes over his wings and moved into a human’s library when train tracks were run through his valley. Know-A-Bit and his sister Frisket used their magic to allow children to experience the world as insects might, letting them “buzz through a hive as bees, or roam through underground passages as ants, or bury themselves like beetles, or fly through the air as gnats.” Through magic, children could see the natural world from a different angle: through the compound eyes of the insects they encountered every day.

In these scientific fairy tales water and ice become sculptors, carving hills and valleys. Coal is a gnome long trapped underground, held fast until freed by magic (or a match). Microscopes and telescopes are turned into magic wands that can make the invisible visible. Flying carpets assist geography lessons, while seven-league boots make quick work of long-distance travel.

With fairies came monsters. What are microorganisms swimming under the lens of a microscope but sea monsters? What are dinosaurs but dragons? Natural-history illustrator Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins reimagined the most famous of England’s dragon legends—that of St. George—by pitting the knight against a pterodactyl. Here be dragons indeed.

Pterosaur-slaying saints aside, the books tended to be scientifically accurate. Meyer taught college-level chemistry before writing about the fairy-based molecule formations in Real Fairy Folks. Whimsical drawings of insects picketing London’s Great Exhibition in Episodes of Insect Life were based on meticulous renderings of the actual bugs. (Episodes was purportedly written by Acheta Domestica—or, if you’re unfamiliar with Latin, the house cricket.) Even though these books were for children, reviewers dealt with them harshly if they deemed their scientific content lacking.

Modern readers may look at these stories and decide it was simpler back then for kids to be kids, without today’s incessant pressure to learn. But 19th-century parents shared our modern concerns, which are illustrated beautifully in a cartoon from 1848 that Keene includes. On the left a child from the past wears a folded paper hat, brandishes a wooden sword, and blares on a trumpet. On the right a child of 1848 stands in a mortarboard and gown surrounded by retorts and electrical coils. This depiction might just as easily be a comparison of the free-range children of the 1950s with the bilingual, tennis-playing, jazz-dancing super-tots of today. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

While Victorian parents may have worried that their children’s lives had lost all wonder through pursuit of knowledge, they had no need for apprehension. After all, just look at the fantastic imagery running rampant through their children’s science stories.

Are today’s concerns valid? Google results for “are kids losing imagination” suggest they are, but ours is the world of Bill Nye the Science Guy, the Magic School Bus, and Mythbusters. That all sounds fun to me. No doubt 50 years from now people will look back on our “simpler time” with equal nostalgia.

Maybe in the end the real worry is not that kids will be deprived of magic, since they so often have ways of making their own. Adults, however, might need a reminder. This too is an old concern. “The analytical tendency of Science,” writes a reviewer in 1853 of the Brothers Grimm’s Household Tales, “which views the Universe simply in its details, might lead us into a morbidly-exclusive perception of the mechanical anatomy of things, were it not for Imagination, which feels and enjoys by the instincts of the heart.” We should strive to keep the wonder in science for children as well as ourselves because, after all, science is wonderful.

The sparkling band of the Milky Way, the toothy smile of a tyrannosaur, the first yellow crocus poking through the snow after a long winter: “Can any magic tale be more marvelous,” asked Victorian writer and science educator Arabella Buckley, “or any thought grander, or more sublime than this?” The world is positively magical, and we should never forget it.

Correction: The original version of this article misidentified the speaker of Arabella Buckley’s quotation. We regret the error.