A few years ago scientists noticed something funny about rodents infected with a one-celled creature called Toxoplasma gondii, or Toxo. Rodents that have been raised in labs for dozens of generations and have never seen a predator in their entire lives will still quake in fear and scamper away from the presence of cat urine; it’s an instinctive, totally hardwired fear. But rats exposed to Toxo, especially male rats, have the opposite reaction. They adore cat urine. At the first whiff the emotion-processing centers of their brains throb and their testicles swell as if meeting females in heat. The finding has fascinated neuroscientists for several reasons, especially for the way it links chemical-level understanding of the brain to large-scale phenomena, such as emotions. Studying Toxo reveals exactly how such leaps in understanding are possible—and why they can be so unsettling.

Originally a feline pathogen, Toxo has diversified its portfolio in the past few million years and can now infect bats, whales, elephants, aardvarks, chickens, and sloths, among other creatures, usually through infected prey or feces. When Toxo invades mammals, it swims straight for the brain, where it forms tiny cysts in the amygdala, an almond-shaped region that processes both smells and emotional states, such as fear and attraction.

Like most organisms, Toxo craves sex, and so it’s always scheming to get back inside the erotic realm of cat guts.

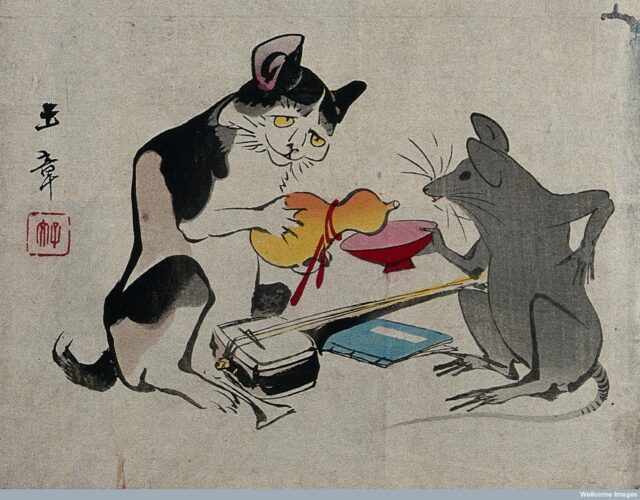

Toxo toys with rodent desire as a way to enrich its own sex life. In every environment except one, Toxo reproduces by simple fission (splitting in half). Unusually for a microbe, though, Toxo can also have sex (don’t ask) and reproduce that way—but only in the intestines of cats. It’s a weirdly specific fetish, but there it is. Like most organisms, Toxo craves sex, and so it’s always scheming to get back inside the erotic realm of cat guts. And cat urine provides a swell opportunity. By making mice attracted to cat urine, Toxo can lure them toward cats. Cats happily play along, of course, and pounce, and the morsel of mouse ends up exactly where Toxo wanted to be all along. Toxo works its mojo in other mammal meals for a similar reason.

Now this might all sound like a just-so story—a clever tale that lacks real evidence. Except for one thing. Scientists have discovered that two of Toxo’s 8,000 genes help make a neurotransmitter named dopamine. And if you know much about brain chemistry, you’re probably sitting up in your chair right now. Dopamine activates the brain’s reward circuits, flooding us with good feelings and compelling us to seek out pleasure. (Cocaine and ecstasy, among other drugs, also meddle with dopamine levels.) Toxo has the gene for this potent chemical in its repertoire twice over, and whenever an infected brain senses cat urine, consciously or not, Toxo starts pumping it out. As a result Toxo gains influence over the creature’s behavior.

The unsettling thing is that humans can also absorb Toxo, either through contaminated food and water or used kitty litter, and fall prey to similar manipulations. Scientists have already correlated amygdala cysts with jealous and aggressive behavior in humans, as well as, oddly enough, slower reaction times. And although it’s speculative, some researchers have suggested that Toxo infections might provide a biological basis for the compulsive hoarding of cats. After all, Toxo wants its hosts to find cats attractive, even to their detriment. Some hoarders, to their great shame, reportedly even crave the smell of cat urine, exactly like mice.

Dopamine contains 22 atoms: that’s it. But from that tiny platform you can leap all the way up to the psychology of fear and attraction—even into something as outlandish as crazy cat ladies.

Toxo isn’t the only parasite that can manipulate animal behavior. Carpenter ants fall victim to a fungus that hijacks their brains and marches the now zombie ants up the stalks of plants to provide a better platform for dispersing fungal spores. A lab-tweaked version of some viruses can turn polygamous male voles into utterly faithful stay-at-home husbands, simply by altering the gene that makes the neurotransmitter vasopressin. Scores of other examples exist.

The vole and Toxo cases edge over into uncomfortable territory for our species since we cherish our autonomy and smarts. One Stanford University neuroscientist who studies Toxo says, “We take fear to be basic and natural. But something can not only eliminate it but turn it into this esteemed thing, attraction. Attraction can be manipulated so as to make us attracted to our worst enemy.” That’s why Toxo deserves the title of the Machiavelli microbe. Not only can it manipulate us; it can make what’s evil seem good.

But if you can get beyond how creepy all this is, Toxo does reveal some amazing things. Dopamine contains 22 atoms: that’s it. But from that tiny platform you can leap all the way up to the psychology of fear and attraction—even into something as outlandish as crazy cat ladies. A little parasite, such as Toxo, seems an unlikely Virgil for guiding us to a more holistic understanding of the brain. But sometimes in science you have to take such friends wherever you can find them.