For whatever reason human beings associate certain animals with pregnancy. Birds and bees. Storks. But in the mid-20th century no animal was more central to starting a family than Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog.

The association between frogs and babies began with British biologist Lancelot Hogben, who had a fittingly dramatic birth in 1895. He arrived two months premature, and his devoutly Methodist parents declared his survival a miracle and promised God he’d become a medical missionary. Hogben did end up loving medical research and led a peripatetic life, but to his parents’ shame he also became an atheist with radical social views, especially on reproduction.

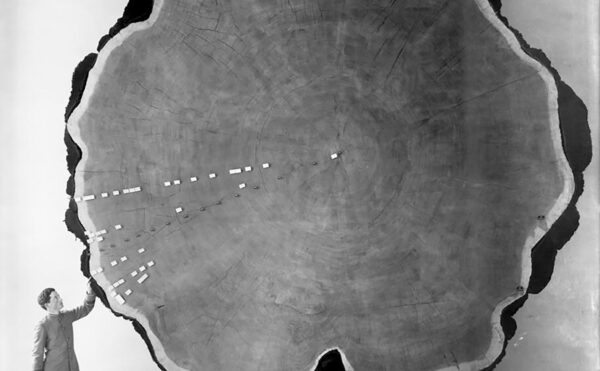

In the 1920s Hogben decamped to South Africa, where he began studying Xenopus, a quirky, tongueless frog. Although brown-green in the wild, these 3-inch-long amphibians turn black when raised in dark environments and white when raised in pale ones. Hogben suspected that the frogs’ pituitary gland controlled this chameleonic action, so he surgically removed it from several specimens. They subsequently turned white no matter the shade of their environments, supporting his theory. But removing the gland led to unwanted side effects, which Hogben tried to counteract by injecting the frogs with pituitary extract from an ox.

To his surprise the female frogs began ovulating. Clawed frogs normally never release eggs in captivity, not without male frogs nearby. But even a drop of ox hormone caused them to eject hundreds of ova, tiny black-and-white spheres that looked like jellied quinoa.

Hogben immediately recognized an application for this discovery. He knew that chemically the ox extract resembled human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a hormone released when human zygotes implant inside the uterus. Because women never make this hormone otherwise, it’s a good early indicator of pregnancy. In fact two hCG tests already existed in 1930. In one, doctors injected urine from women who suspected they were pregnant into baby female mice; if hCG was present, the ovaries in the mice metamorphosed. A similar test involved virgin rabbits. Both tests had downsides, though, requiring multiple injections over multiple days. And to examine the ovaries you had to slay the little critters, an unpleasant task.

Frogs offered an alternative. They eject their eggs, so Hogben didn’t have to kill anything. He could reuse each amphibian multiple times, making the work cheaper. And frogs reacted in as little as five hours, while rabbits took two days, mice five. But Hogben’s work was interrupted when, disgusted by South Africa’s increasingly racist policies, he left for England in 1930. He imported a stock of clawed frogs to his new lab in London, and within a few years he and his assistants had developed a standard pregnancy test. A woman could now determine whether she was pregnant just one week after first missing her period.

If her doctor allowed her to take the test, that is. Doctors traditionally used the mouse and rabbit tests to distinguish between pregnancy and certain maladies that stopped menstruation: anemia, tumors, endocrine problems. They also wanted to detect pregnancies as early as possible in women with tuberculosis or weak hearts. But most doctors opposed routine pregnancy tests, arguing that lab work should be reserved for medical emergencies, not used for mere convenience. Some doctors also feared a spike in illegal abortions.

But women’s advocates persisted. Both medically and psychologically, they argued, women benefit from knowing as early as possible about pregnancies. And Hogben’s frog test eased the fear about the ruinous costs. By the late 1940s labs around the world had whole teams of technicians, mostly women, injecting the little croakers with urine. This remained the standard pregnancy test for 15 years until a scientist in Buenos Aires discovered a similar reaction in certain male frogs, which release sperm when exposed to hCG-rich urine. This test proved even faster, sometimes confirming pregnancies within an hour.

Hogben kept wandering in later life, accepting jobs in Norway and Wisconsin. Scientifically, he drifted as well, first into research combating eugenics theories and then into studies of drug-resistant bacteria. But his pregnancy test was a bedrock of women’s health through the 1960s, when chemical assays replaced it. In a topsy-turvy way, then, Hogben did end up fulfilling his parents’ wishes of becoming a medical missionary. It’s just that instead of helping women around the globe himself, he sent in his stead a hardy, 3-inch amphibian with a quirky biochemistry.