Decorated Soldiers

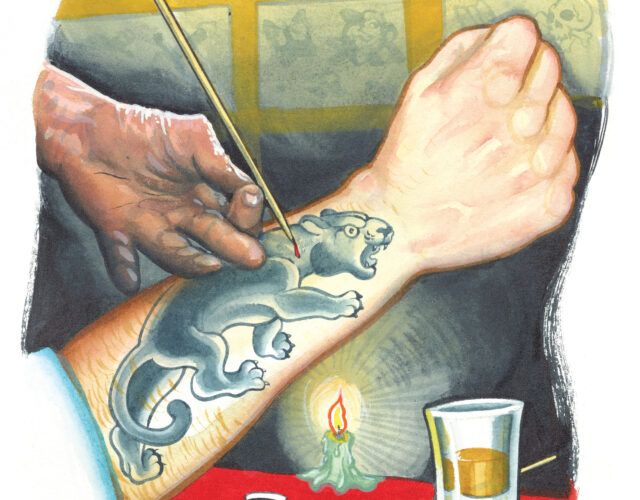

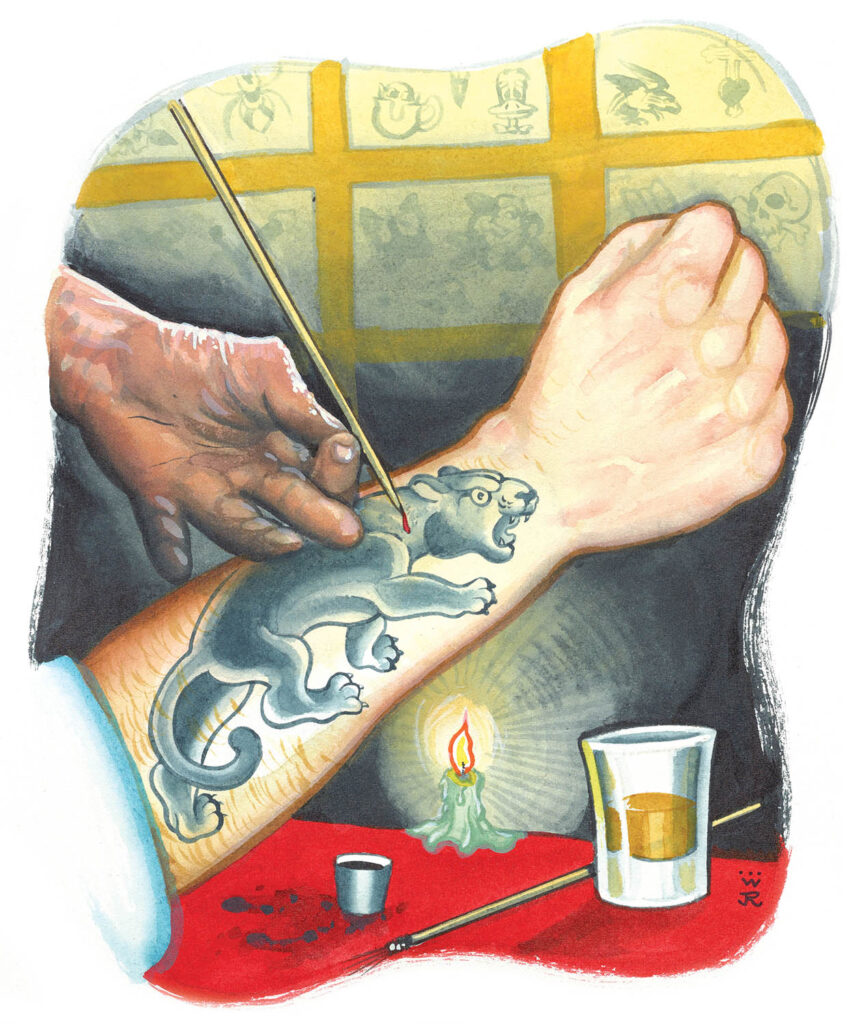

My dad had a panther; now he has a scar. He got it in the navy in the 1960s. The panther, not the scar.

Frank Klett was born in 1944 in Montclair, New Jersey. He joined the navy while in high school and shipped out shortly after graduation. He got a tattoo of a panther in 1964 while stationed in Hong Kong.

When I asked him about it 50 years later, he recalled the makeshift parlor: “I wouldn’t give it credit for being a storefront. It was like a door in an alley, and you go down some stairs and around a corner is an old guy sitting there with a candle sharpening his needles.”

Outings like this were fueled by beer and macho competition between shipmates. There wasn’t much planning ahead.

“I remember that he did it the really old-fashioned way. It was not electric. It was a bamboo stick. And he would tap the other end of it and—tap-tap-tap-tap—it was all done manually.”

Tattooed in all black ink, the panther was rendered in profile, leaning forward in cool alert with its tail curled under its hind feet. It’s gone now, the panther. When it was around, and I was a kid, it seemed like an extension of my father’s personality. I never imagined it might go away. Why would it? How could it?

I have a few photos of the tattoo. Show one to a professional tattoo artist today, and you’ll hear that my father’s panther was unique. The sideways view and mellow disposition never really caught on, even in recent years as tattoos have gained popularity.

My dad figures about half of his fellow sailors had a visible tattoo. In the 1960s it was uncommon to see a tattoo in civilian life. At the time, tattooing was illegal in several states, which made tattoos difficult to get unless you “knew a guy.” But sailors circulated more widely than other branches of the military, and their travels took them to ports of call where tattooing was readily available. Superiors warned that tattoos were prohibited for health reasons—but they had little recourse once you got one.

In the eyes of other sailors what tattoo you had mattered less than that you had one at all. These informal insignia created a meaningful distinction. As my father puts it, “We traveled the world more. Like we know everything there is to know, so we can have tattoos.”

And travel he did. After seven years sailing the Caribbean and the Mediterranean, my father volunteered for the Vietnam War by taking a job operating a radar system on the South China Sea. This was 1968.

Following a year in language school, my father took up residence in a lighthouse with a unit meant to monitor weapons and ammunition moving north to south. A relic of French colonialism, the lighthouse was “a pile of rocks” where he and his unit monitored ship traffic, bartered with locals and allied soldiers for food, and tried to keep their gear from rotting in the perpetual wetness.

After the signing of the Paris Peace Accord in January 1973, the American military had to leave Vietnam before the cease-fire could begin. Around this time my father was promoted to operations specialist and assigned to the evacuation of Saigon. After weeks of shipping off people and equipment, my father boarded a 747 with the last 69 American soldiers in Saigon. He wore no uniform because all of them had been eaten by rodents. He had a bullet wound in his shoulder, and he was critically underweight from a prolonged bout of dysentery. He was so undernourished that medical staff rerouted him, midflight, from Pearl Harbor to San Diego.

The Panther Disappears

Trace the arid freeways and chaparral gulches north from San Diego Bay, and you will reach the Naval Medical Center San Diego. Perched on the western wall of Florida Canyon in historic Balboa Park, the center is memorable for its Spanish colonial design, pink stucco, and scenic views.

It is here the newly released Frank Klett, now three months out of Vietnam, emerges into the yellow sunshine of Southern California. He has recovered from the infection that cost him nearly half his body weight. With nothing urging him home to New Jersey, he considers his surroundings and takes an assignment at a local naval station. In the California sun the panther skulks in the shade of Frank’s rapidly browning skin.

We talk about tattoos as permanent marks, as if they never change in appearance or meaning. But in reality tattoos change; they age with us, and they are affected by our environments and the technologies we encounter.

Frank leaves the navy in October 1979. He is 35 years old, married, and parenting two stepchildren and a newborn. The family lives in another canyon about 13 miles north of Balboa Park in a suburb built for faculty and staff of the University of California, San Diego. Frank’s car, house, and pants all converge on shades of beige—trading one monochrome uniform for another.

Frank uses his experience with radar to land a job in computer engineering, and the work brings him in contact with a new kind of educated, middle-class worker. These new colleagues are less accustomed to forearm tattoos. The panther spends workdays hidden under long sleeves of polyester blend. Saturdays in the yard and Sundays on the beach create a further conflict for Frank and the panther. Sun exposure causes the ink to crystallize in a painful mantle under his skin. Frank decides the panther has to go.

In a nondescript room on an unremarkable floor of a modern medical building, Frank has his panther tattoo removed by laser. This particular laser works by exciting the electrons in carbon dioxide gas to produce a beam of infrared light. The laser melts the flesh until the layers of ink are exposed and burned away. The burn is so severe the doctor only treats a square inch of skin at a time. Each treatment takes six weeks to heal, and each visit costs $100. Frank goes every six weeks for a year.

After treatment the panther is no longer visible, but a pale scar the size and shape of the panther remains. The laser has burned off Frank’s melanin along with the tattoo’s ink, so the spot won’t tan. Frank continues to wear long sleeves to hide the scar.

We talk about tattoos as permanent marks, as if they never change in appearance or meaning. But in reality tattoos change; they age with us, and they are affected by our environments and the technologies we encounter. Meanings change as well. A tattoo can be a powerful marker of belonging or in other circumstances a tremendous stigma. For people seeking a second chance at life, the tools available can ultimately decide how much of their past can be shed and at what cost.

Frank endured a lot of pain, expense, and scarring for a second chance. Only a few years later a new kind of laser wasn’t just replacing one mark with another. Rather, it was making tattoos disappear completely.

Can Lasers Change Your Life?

Follow the canyons north of San Diego, and you will find fingers of suburban cul-de-sacs spreading through thickets of scrub oak, sage, and sumac. You will cross ravines gone yellow with drought; suspended freeways of 10, 12, and 16 concrete lanes; and campuses and industrial parks housing an exploding biotechnology industry.

Situated on one such campus is the Beckman Laser Institute (BLI). Located 80 miles north of San Diego at the University of California, Irvine, BLI is a single structure surrounded by an asphalt parking lot. Walled with concrete bricks, the institute is topped by a series of slanting red roofs. This detail, like so many others, was the vision of the founding director, Michael Berns, who first conceived BLI in 1982. The whole structure was built to order, and it took four more years until the paint was dry and the institute was ready to open.

The laboratory spaces inside BLI are filled with metal racks of wires, computers, and other technology befitting the institute’s namesake, Arnold O. Beckman, the man behind many of the most influential instruments used in chemistry and biology in the 20th century. Beckman’s pH meter transformed the California citrus industry in the 1930s, and his inventions were integral to measuring automobile smog production in mid-20th-century Los Angeles.

Rather than melt the layers of skin to uncover the ink, Q-switched lasers produce infrared light that passes through the upper layers of skin to target a specific pigment in the tattoo ink.

The idea of BLI began as a collaboration between Berns and Beckman, who wanted to create a place where clinical practice would help accelerate the research and development of new medical instruments. BLI would unite the clinic and basic science through a single technology: lasers.

Around the time Frank Klett was tattooed with a bamboo needle, researchers were running an electric current through a gas-filled tube to encourage electrons in the gas molecules to emit light. Mirrors at each end of the tube reflected that light back and forth, exciting more electrons and thus adding to the flux of light that the mirrors then focused into a beam with a specific frequency, such as infrared. In the decades that followed this discovery doctors began using these controlled bursts of light to target biological processes within the body. Early lasers could not penetrate the skin without breaking it. Later, more sophisticated versions affected internal processes with minimal external damage. BLI in particular developed lasers for the detection and treatment of various types of cancer, the monitoring of internal bleeding in stroke patients, and an assortment of dermatological therapies.

The clinical part of BLI’s mission is carried out in a row of operating rooms with beds and sinks typical of a modern medical theater; less typical are the colorful braids of cords and trays of protective glasses used in laser surgery. The laser itself is a wheeled cube no bigger than a filing cabinet. On it is a monitor and an arm on which a cable hangs. At the end of the cable is a hand-held applicator wielded by J. Stewart Nelson.

Nelson is a former graduate student of Berns. He became the institute’s medical director during the first year of operation. Nelson’s tenure at BLI corresponds with the invention and development of a new kind of laser called Q-switched. Whereas previous lasers produced a constant beam, Q-switched lasers work by pulsating energy in rapid bursts. While Q-switching is heralded for allowing less-invasive surgeries on internal organs, it also has improved dermal therapies, such as removing tattoos. Nelson explains,

Rather than melt the layers of skin to uncover the ink, Q-switched lasers produce infrared light that passes through the upper layers of skin to target a specific pigment in the tattoo ink. Nelson calls it an “exponential improvement” on those continuous beams to which Frank lost his panther. “Essentially you replaced one mark, the tattoo, with another mark, namely, a scar,” Nelson says of the old treatment.

By tuning in to the spectrum of color in tattoo ink, Q-switched lasers do no lasting damage to the skin. “The patient doesn’t have an open wound. It’s not painful; it’s well tolerated,” Nelson says. And unlike gas lasers, “These procedures rarely produce scarring.”

A poster near the BLI entrance asks, “Can Lasers Change Your Life?” Displayed are before-and-after images of skin conditions that lasers in the clinic might remove: birthmarks, spider veins, discoloration, tattoos. The last category stands out. Of the lot, tattoos are the only marks we choose, the only marks that are deliberate. To remove a tattoo is to do something deliberate—again.

Inside BLI’s operating rooms, where the laser retraces the needle of the tattoo artist, it is common for patients to talk of “erasing” mistakes: the cursive script of an ex-lover’s name, garlands on the lower back, swastikas and other symbols of hate. The BLI’s lasers are erasers that actually remove, with little or no trace, the marks of a person’s past.

Berns and Nelson weren’t picturing tattoo removal when BLI first opened. But after a couple of years—and the intervention of a local judge—tattoos and the people who have them became regular visitors.

This Huge Volume of Humanity

From the crest of the road leaving BLI, you can see the smoggy horizon of Los Angeles County. At this distance downtown L.A. is a cluster of spikes rising from concrete sprawl. From there to here you can trace the multilane freeways that connect Los Angeles and Orange County. The city is visible yet worlds away.

Due north of Irvine is the city of Santa Ana, which shares a name with the hot, dry winds that regularly drive wildfires through the canyons of Southern California. The city is flat and organized from end to end on a neat grid. At the city center, located on a long block of tinted windows and modernist municipal design, is the Orange County Superior Court. From 1981 to 1998 this was home to the courtroom of Judge David O. Carter.

In the 1980s Carter was a superior court judge in charge of the master calendar. His job was to process all the court’s criminal cases. Each year there were thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, of cases. Maybe half ended with a plea bargain. The point was to deal quickly with lesser offenses—selling or possessing narcotics, burglary, writing bad checks—and free up the felony court for assault and murder cases.

“You can’t understand how difficult it is for somebody who has tattoos all over their face, neck, and arms and hands to get employment.”

Whatever the outcome of these trials, the sheer number of defendants that passed through Carter’s courtroom was staggering. “You have to imagine this huge volume of humanity,” Carter says in 2017, recalling his former courtroom. “Picture a courtroom with 200 people in it. Attorneys lined up against the wall. Prisoners coming up 70 at a time. Average calendar: 120 people a day.” About a third of the defendants in Carter’s courtroom were held for parole violations, meaning many had already passed through the court. Some became familiar faces. Carter didn’t like that.

“As a judge you start making decisions,” Carter says, “how rehabilitative do you want to be versus how punishment oriented.” At the time, many of Carter’s colleagues subscribed to a doctrine of “law and order”—a punishment-heavy approach to justice institutionalized through the court nominations of President Ronald Reagan. Law-and-order policies led to a 500% increase in California’s prison population from 1982 to 2000, with much of this growth attributed to convictions for drug possession. In this system rehabilitation was largely an afterthought. The idea that a judge might intervene in the lives of prisoners and parolees was derided by other judges, Carter recalls, as “social work.” Under law and order the lives of the convicted were irrelevant to the pursuit of justice. But Carter thought otherwise. He believed punishment without rehabilitation would only create more injustice. He believed the court could and should provide a second chance.

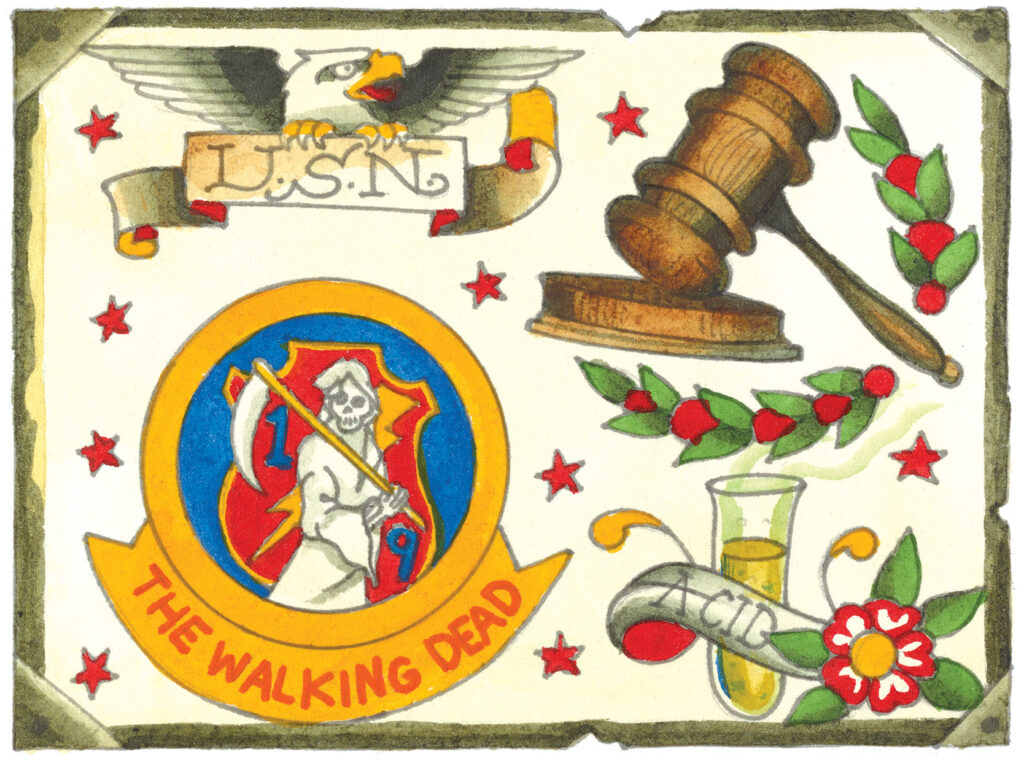

Carter’s philosophy comes from experience. Before practicing law Carter served in Vietnam as part of a unit known as the Walking Dead, an infantry battalion of the U.S. Marine Corps. During the Vietnam War the battalion suffered the highest casualty rate in Marine Corps history, with 25% of the soldiers killed in action. Many more returned home with lasting injuries. In addition to high rates of heroin use among active-duty soldiers during the war, the use of prescription opiates to treat chronic pain led to widespread substance abuse after the war. To add insult to injury these soldiers returned home not as heroes but as perpetrators of the least popular war in American history.

Five years after Frank evacuated Saigon, veterans made up 25% of the American prison population. Looking back on that time, Carter says, “I was thinking about how many kids were out there on the street who had served honorably and had just gotten whacked out.” He recognized the behaviors that get people in trouble with the law are not reserved for a few bad apples; behaviors result from circumstances that can affect anyone.

As a judge Carter takes what he calls a “holistic” approach to rehabilitation. As he explains it, the parolees appearing in his court had already been punished by serving their time; now it was time for the court to serve them. In his courtroom he began to offer basic resources for civilian life: referrals to a food bank, clothing, or child care; advice on buying a car for work; help finding a job. Jobs are critical to Carter’s approach because they provide an income and a sense of duty. Plus, when you’re working, you don’t have time for things that might get you in trouble.

Carter saw employment as essential to civilian life, but he recognized something was keeping many parolees from getting jobs: their tattoos.

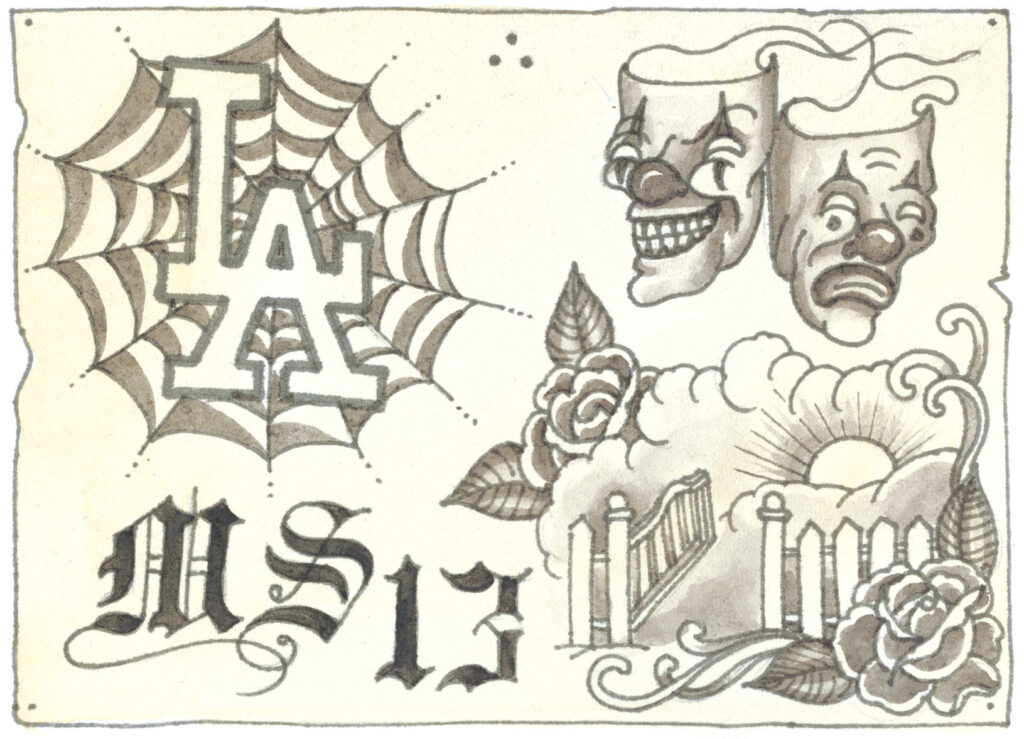

“You can’t understand how difficult it is for somebody who has tattoos all over their face, neck, and arms and hands to get employment,” Carter says. Tattoos, particularly gang tattoos, were made to be seen. This creates a physical challenge to leaving gang life behind. “The Aryan brotherhood, with lightning bolts or 666 for the devil, or Hispanic gangs, with three dots, happy face, or clown face—you can almost read tattoos like a book. Gang members, at least hard-core gang members, were literally walking billboards for their gangs.” As he came to appreciate the challenge tattoos presented, Carter wondered, what if you remove the tattoos?

In 1984 the judge began exploring options. “We initially went to a couple private practitioners who claimed that they could take tattoos off with acid,” he recalls. “Well, that didn’t work too well.” Carter’s first volunteer had a tattoo removed from the back of his hand. The results, Carter recalls, were “god-awful.” He searched for a better solution, looking into advertisements by for-profit clinics. “I was hearing for the first time that there was something called laser, which sounds so common now, but back in the 1980s this was the brave new world. Lasers? What are those?” Carter wondered. “And why would they work on tattoos?”

Such questions became moot when he saw the costs of laser treatment. No way could his parolees afford thousands of dollars to remove their tattoos.

A breakthrough came when Carter began teaching an evening class at UC Irvine in 1987. There he discovered a new institute had just opened that was dedicated entirely to lasers. He arranged a visit and, impressed by the sophisticated arrangement of the BLI facility, shared his vision with Michael Berns. “ ‘Well, you know it’s expensive,’ ” Carter recalls him saying. “My response was, ‘Well, I don’t have any money.’ ”

So Carter and Berns worked out a deal: BLI would donate the treatments if the patients covered a small fee for use of the clinic once a month. At first, with just a handful of parolees volunteering, Carter paid the fee himself.

Carter’s thinking was pragmatic: “We didn’t have enough resources to remove all of the tattoos on your arms, or your chest, or your back—that was tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of work. But we could remove the tattoos on your face and neck, and maybe that would give you a chance of employment, but probably you still had to wear a long-sleeved shirt.”

The Nice Thing about Face Tattoos

Nelson was there the day Carter first visited BLI and has overseen the program from the beginning. “At any given time we probably have about five patients that are in the program,” Nelson says. “When one finishes, they’ll send us another one or two over.”

Nelson volunteers one morning a month—Carter likes the patients to get up early as a test of commitment—usually a Tuesday or Wednesday. During intake Nelson asks about the history of the tattoo to be removed. When did you get it? How? Was the artist amateur or professional? After a brief physical exam the patient is taken into the treatment room.

The procedure takes less than five minutes per tattoo. The patient will sit or lie down on a surgical table in the middle of the treatment room. The doctor sits alongside the patient, much like the tattoo artist originally would have. Everyone wears eye protection. The doctor works by tracing the tattoo with a laser applicator, millimeter by millimeter. It sounds like the clicking of a starter on a gas range. Each pulse of the laser produces a flash of light, and wherever it strikes immediately turns white. This is actually steam under the skin: as the ink heats up, it releases moisture. Patients say the laser feels like the snap of a rubber band or a burn from hot grease.

Nelson has used Q-switched lasers since the start of the program, though now they work about twice as fast. “The laser will deliver up to 10 pulses a second, so it’s basically like me going like a machine gun over the area very, very quickly,” Nelson says. Within 20 minutes the steam will dissipate, and within a week the ink will be noticeably lighter. Patients experience only light scabbing in the days that follow, and recovery between treatments lasts only a few weeks. While some tattoos fade with just 3 or 4 treatments, others can take 10 or even 15 visits. Nelson says he lets the patient decide how many treatments they need.

The kind of ink used in a tattoo determines how it will react to laser light and ultimately how effective the results will be. Amateur tattoos, such as those made in prison, respond well to laser light because they’re made of simple materials, such as carbon and graphite. This material produces a dark, blue-black ink that absorbs almost the entire spectrum of visible and near-infrared light. (Frank’s panther would have been an ideal candidate for Q-switched laser.)

Other colors of pigment, and especially those used by professional tattoo artists, are more challenging. Inks are made with different chemical compounds, including metals added to produce bright colors. While great for rendering tattoos, these materials can be terribly difficult to remove. “Red tattoos we can target with green light specifically, so those are fairly easy to get out. But, the organometallic dyes that are in blue, turquoise, those green colors, yellow, those can be very, very difficult colors to get out.”

Nelson uses the analogy of cars in a parking lot: “If you’ve got a black car, infrared light is going to be absorbed. If you’ve got a white car or a yellow car, it’s not absorbing the light. So if somebody’s got a multicolored tattoo that’s not absorbing the laser light, it doesn’t matter how high the energy I put there. The light is not going to be absorbed and then converted to this mechanical energy to disrupt the particles.”

The success of Q-switched laser removal also depends on where the tattoo is placed.

Ink placed in deeper layers of tissue is stubborn. Nelson refers to these deeper layers as “optical windows.” The more tissue between the ruptured ink and the blood vessels, which will carry it away, the thicker the window and the more likely bits of ink will remain in the skin. This resistance is compounded when lasers attempt to penetrate darker skin, which responds like a tinted window.

But Carter’s focus on conditions of employment means these resistant areas are a nonissue. As Nelson explains, “The nice thing about the scalp and face is that they’re very vascular”—meaning less tissue and plenty of blood vessels—“so those areas actually respond really, really well.” In a twist of fate highly visible tattoos are seen as the greatest barrier to civilian life—yet they are also the best candidates for laser removal.

Nelson says his job is to treat all tattoos the same. “These are people that are like, ‘Hey, man, I made a mistake. I want to correct the mistake.’ And I totally get that. I tell them I’m in the mistake correction business. I’m not here to judge you.”

Second Chances

In November 2016 BLI celebrated its 30th anniversary; Nelson was one of five faculty members who had worked there since its inception. Except for taking a program hiatus from 2000 to 2008, he remains the resident in charge of treating parolees. Nelson guesses he’s treated as many as 200 patients since the beginning. In 2011 he was formally honored with an award for his efforts. The ceremony was held at Carter’s current chambers in Santa Ana—located in the Ronald Reagan Federal Building and Courthouse.

Nelson describes his role in the program as “trivial,” equating it to jury duty. Yet this diminishes just how essential a part he plays. Second chances aren’t simply given; they take work, sometimes a physical transformation, to be earned. In everyday encounters veterans of gang life—or the military for that matter—can find they’ve been “reenlisted” by the perceptions of others. Changing appearances can be a vital step in changing a person’s life.

It is hard to estimate the impact of tattoo-removal programs such as the one at BLI. There simply isn’t enough data to quantify. That will change as similar programs continue to appear around the country. In the meantime we have the personal stories of those who have found a new sense of self by removing their tattoos.

Alex Sanchez is executive director of Homies Unidos, a Los Angeles–based organization for men and women seeking alternatives to gang life. Sanchez helped establish the group for those people who, like himself, have struggled to shed their affiliations to Mara Salvatrucha Trece, better known as MS-13, which began in the early 1980s among Salvadoran youth in the Pico-Union and Koreatown neighborhoods of Los Angeles.

Members of MS-13 are notorious for their extensive tattoos. Sanchez says gang tattoos act like a protective “shield” for young people, one that allows kids to move around their neighborhood without fear of being harassed. That’s how it played out for Gerardo Lopez, who joined MS-13 when he was 14 years old. He was interested in graffiti, not violence. But as he grew, he received the unwanted attention of local gang members. Joining a gang of his own seemed a necessary step to avoid bullying.

Lopez emphasizes that tattoos were not required for membership. “Nobody told me I had to get a tattoo,” Lopez says, “but I wanted to feel more connected.” He sees tattoos as a “fashion statement” that allows members to feel more invested in the gang:

Yet for many young people the protection and identity tattoos provide end up shielding them from new opportunities as adults. The effect is alienation from both gang and society.

At age 22 Lopez felt he had “mentally” left the gang. Yet he still had his tattoos. He compares these marks to a team jersey from years ago. “It’s almost like when you’re in high school and you’re on the football team and you’re wearing the jersey. All of the sudden years have passed by and you’re not in high school no more and that football jersey doesn’t fit you anymore, but you’re still wearing it.”

What drove both Lopez and Sanchez to remove their more visible markings was not their former gang but the rest of society: law enforcement, potential employers, and neighbors. “I did not want to be a target,” Sanchez says.

Tattoos, particularly on brown skin, make for easy stereotypes. Lopez explains, “You see a white person with tattoos and people look at it as art. You see a Mexican person with tattoos and people look at them as a cholo or a chola [gangster].”

“I’ve seen kids, they take off their tattoos and then all of a sudden they put them back on because they didn’t have nothing to fill that void.”

Homies Unidos offers a three-month-long workshop to help young people make the transition from gang life. On completion the organization will help pay to have tattoos removed at clinics with lasers like those at BLI.

Despite what I was told by doctors, Lopez reports the treatment is anything but painless. Lopez has had dozens of treatments to tattoos on his neck. “Brutal,” he says. “It hurts about 10 times more than when you’re putting them on.”

It is hard to generalize the experience of being on the receiving end of a laser. Lopez says the pain of treatment can be profoundly emotional. “You’re not only stripping the tattoo. You’re stripping off stories, layers of stories and layers of pain and layers of trauma.”

Tattoos are more than mere marks on the body. They are meaningful, especially for the people who decide to get them. “I’ve seen kids, they take off their tattoos and then all of a sudden they put them back on because they didn’t have nothing to fill that void,” Lopez explains. “You’re pretty much stripping off their identity, so you [need a new one] to give to them.”

Talk of second chances can bring to mind a dramatic break in a person’s history. Indeed, when Sanchez began his first treatment, he says he felt like “a traitor.” Yet his departure from the gang was uneventful. He says there were no denouncements. No threats. No violent “jumping out” ceremony. His encounters with members of his former gang were relatively peaceful; several joined him to remove their own tattoos. Lopez reports a similar experience.

Through removing their tattoos Sanchez and Lopez realized they are not escaping anything. They are growing, and in the process they are showing others how they too can grow, as Lopez says, “organically.” It is hard to imagine an outcome any closer to the one Carter envisioned.

Carter is now a federal district court judge. He travels often in a diplomatic capacity to counsel court officials and policy makers in other nations. Though no longer a probate judge, he continues to advocate for rehabilitative measures like the tattoo-removal program at BLI: “It’s not something that has to be vetted. It just takes compassion and a willingness to work together in different sectors. I frankly don’t think that they’ve received enough notoriety for their good works.”

Anecdotally, Carter cites a significant drop in recidivism among those who went through the BLI program. As parolees commit to a series of treatments, he notes, they commit to new routines that seem to keep them out of his courtroom. Carter stopped seeing so many familiar faces and says he couldn’t be happier.

But technological solutions to social issues are never perfect. Second chances take work. And they don’t always stick.

My dad dropped out of the white-collar world about 10 years after he removed his tattoo. Laser treatment offered him some distance from his identity as a sailor, but it got him no closer to the person he thought he would become. He kept searching, leaving San Diego behind as well.

Today, Frank has no regrets about removing his tattoo, even though it wasn’t necessary to his livelihood. Shedding that ink was simply a way of letting go of the person he used to be.

Jeff Rassier created the drawings for this article. He has done illustrations for skateboards, comic books, snowboard companies, record labels, beer labels, and magazine articles, and is a full-time tattooer at Black Heart Tattoo in San Francisco. Rigoberto Hernandez, video and podcast producer for Distillations, contributed reporting to this article.