Catherine Price. Vitamania: Our Obsessive Quest for Nutritional Perfection. Penguin Press, 2015. 318 pp. $27.95.

The early history of nutrition—in particular the discovery of those micronutrients we call vitamins—includes stories of near mythic proportion, pitting “men of science” (and they usually were men) against ignorance and dread disease. Perhaps best known is the story of 18th-century English naval surgeon James Lind, who treated his bloody-gummed, emaciated sailors with oranges and lemons to cure them of scurvy—a disease that often killed half a ship’s crew on long sea voyages. Lind was not the first to treat scurvy with diet, but he was the first to carry out a systematic experiment on his suffering crew, thus proving the dietary value of citrus fruits. He published his findings in 1754 in A Treatise of the Scurvy, but it would take another 150 years before the idea of “vitamin C” was established.

The research of Dutch physician Christiaan Eijkman involved a disease as horrific as scurvy but less well known in the Western world. Eijkman was stationed in the Dutch colony of Java in the 1880s studying beriberi, a paralyzing and ultimately fatal disease endemic to much of South and Southwest Asia. In place of human subjects, Eijkman experimented on chickens suffering beriberi-like symptoms. A serendipitous change in the chicken feed led Eijkman to connect this debilitating disease to diets with polished rice as their staple. He concluded that beriberi was prevented by ingestion of a mysterious substance present in rice “polishings,” or bran. Eventually researchers would identify vitamin B1 (thiamine) as Eijkman’s “anti-beriberi factor.”

Pellagra, another nearly forgotten disease, haunted the American South throughout the early 20th century. The disease caused severe skin disfiguration followed by diarrhea, dementia, and death. In 1914 Joseph Goldberger, a physician with the U.S. Public Health Service, was assigned to investigate the pellagra epidemic. His experiments with diets in state orphanages, asylums, and prisons led him to connect pellagra to an essential factor absent from a poor, corn-dependent diet, but his conclusion was unacceptable to many Southerners who saw it as a slight on their way of life. In the late 1930s Goldberger’s “pellagra-preventive factor” proved to be vitamin B3 (niacin).

These individuals played a seminal role in the discovery of vitamins and in furthering our understanding of nutritional deficiency disease. Their stories provide a springboard for journalist Catherine Price to pursue a more complex narrative in her book Vitamania: Our Obsessive Quest for Nutritional Perfection—a quest that takes us from Lind’s lemon-sucking sailors to the well-stocked shelves of such retail chains as the Vitamin Shoppe. Price examines the origins of our nutritional anxieties and our readiness as consumers to reach for the latest vitamin, mineral, herb, or enzyme advertised as restoring, revitalizing, or enhancing health and increasing longevity.

The discovery of vitamins introduced a powerful new way to understand the interplay of health, disease, and diet, although it took several generations and the accumulated work of many men and women for the new ideas to be accepted. The notion of “deficiency diseases”—diseases caused by something missing in the diet rather than by the presence of a toxic substance or infectious organism—required a change in perspective on the part of scientists, medical practitioners, and the public. The change was made more difficult because these mysterious substances could not be isolated, seen, or measured. Their absence caused horrible diseases, yet health was miraculously restored by seemingly small corrections to diet. But once the tools and techniques of scientific investigation caught up to the idea of vitamins, the discovery, isolation, and chemical synthesis of what we now regard as the 13 essential vitamins occurred fairly rapidly. In 1929, B1 was the first vitamin to be isolated and crystallized. By the end of the 1950s all 13 essential vitamins, with the sole exception of B12, had been synthesized. Ten Nobel Prizes were awarded for work in vitamin research (all between 1929 and 1943), the first to Christiaan Eijkman.

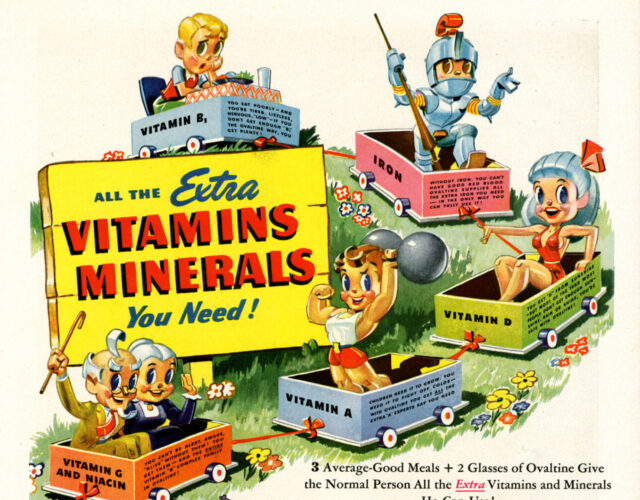

Vitamin discovery, however, is not the vitamania Price is chiefly concerned with. Somewhere along the way the story of scientific discovery and nutritional knowledge turns into a story of products and profits, where the consumer is often a pawn in a political battle waged between a highly lucrative industry and federal regulators. Price credits journalist Robert W. Yoder with coining the term vitamania in a 1942 article in the popular health magazine Hygeia. By this time the vitamin pill, unheard of before the 1920s, had become a profitable commodity and was quickly becoming part of the daily regimen of ordinary Americans—Americans who were certainly not suffering from the debilitating deficiency diseases of past generations.

Part of the vitamin industry’s rise can be attributed to advances in organic chemical synthesis and industrial processes that made pills relatively cheap to manufacture. The price of bulk vitamins, produced by such leading American pharmaceutical companies as Roche and Merck, dropped dramatically between the 1930s and early 1940s. At the same time, American homemakers were inundated with information about vitamins and the new science of nutrition. Popular women’s magazines, such as McCall’s and Good Housekeeping, helped spread the vitamin gospel through, for example, the regular health column authored by scientist Elmer McCollum, a man revered in the nutrition field for his work in the 1910s that led to the discovery of vitamins A and D. While McCollum preached the importance of a balanced diet in which whole foods provide all nutritional needs, advertisements in the pages of the same magazines suggested an easier solution to the uncertainties of meal planning—vitamin pills.

The history of federal regulation is one of continual compromise between public health and private enterprise, individual freedom and government protection.

Nutrition became a national issue during World War II as the U.S. government focused its attention on the physical and mental well-being of its population. Studies of Americans’ dietary habits begun in the 1930s suggested that a majority of Americans were not getting adequate nutrition. Adding to this anxiety was the increasing knowledge that food processing, from canned fruits and vegetables to refined flour, had robbed foods of much of their natural nutritional value. By 1942, when nearly a quarter of Americans were taking vitamin pills, food manufacturers were pumping tons of synthetic vitamins back into depleted foods, creating innumerable products “enriched” or “fortified” with vitamins.

The vitamin industry flourished after the war, rooted as it was in the rapidly expanding pharmaceutical industry and firmly backed by “science,” at least in the minds of consumers. Today vitamin products are just one segment of a much larger category of products known as dietary supplements, which include herbs and botanicals, amino acids, and other substances found in the human diet, such as enzymes. Price regards vitamins as “gateway drugs” for having paved the way for the emergence of this much bigger industry, an industry that in 2012 alone racked up $32 billion in sales.

These days almost all foods, drugs, supplements, cosmetics, and medical devices—from our breakfast cereal and lip gloss to our most potent pharmaceuticals—are regulated by the FDA. The history of federal regulation is one of continual compromise between public health and private enterprise, individual freedom and government protection. Over time the scales have been tipped in favor of one side or another, and some industries (and individuals) have protected their own interests better than others. Price, in relating the history of FDA regulation, shows how the dietary supplement industry has been particularly successful at playing this game. The industry has been adept at using political influence—including such powerful allies as Senator William Proxmire in the 1970s and Senator Orrin Hatch in the 1990s—along with shrewd public campaigns to advance its interests. Since the 1960s industry lobbying groups with disingenuous names, such as the National Health Federation or the Nutritional Health Alliance, have repeatedly and successfully fought against legislation to increase federal regulation and oversight.

Surveys show that few American consumers are aware that the supplement industry is not required to provide any evidence that their products are safe or effective before they are put on the market. The only exception is for “new dietary ingredients,” supplement ingredients introduced after October 15, 1994. Since the passage of the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act in 1994, the burden of proof is on the government. There is no legal requirement for premarket testing of supplements, so the FDA cannot effectively act until adverse reactions and health problems have already occurred and been reported. Ephedra, a weight-loss aid and athletic-performance enhancer, is the only supplement banned by the FDA, although actions short of outright banning have been taken against other products. There is no FDA approval process for dietary supplements, as there is for other drugs because supplements dwell in what the FDA terms the “umbrella” of foods. But while the FDA requires health claims on foods to be backed “by significant scientific agreement,” dietary supplements are not held to this same standard. Instead the health claims in supplement advertising are followed by a telltale asterisk, leading to the disclaimer, “This statement has not been evaluated by the FDA. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

While Price certainly equates federal regulation with consumer protection, not every reader will share this conclusion. As citizens we hold a wide range of beliefs about the proper role of government, particularly when it impinges on our perceived freedoms as consumers or entrepreneurs. And although some tragedies may have been prevented by more federal oversight—such as an incident of contaminated L-tryptophan (an amino-acid supplement taken for insomnia) in the late 1980s—most of the harm done has probably been to our pocketbooks. Numerous scientific studies have failed to demonstrate the long-term health benefits of supplements. That there is much about vitamins and other micronutrients that we still do not know is a recurrent theme in Vitamania. Although pseudo and superficial science has been used to hawk innumerable products, when it comes to substances purporting to affect our health and vitality, we, as consumers, are particularly vulnerable. Anyone who takes supplements, or anyone who wonders if they should take supplements, will find much food for thought in Price’s book.