In book collecting there is rarely anything quite as good as the first edition. But of the rare instance when a later edition is genuinely more interesting, there is no better example than the third edition of Isaac Newton’s Opticks (1718).

It was not until 1704, 30 years after Newton had made his groundbreaking discoveries, that he decided to publish the original Opticks. Even then he was reticent about unveiling some of his conclusions. The problem was forces acting over very short distances. The newly invented microscope had shown even a seemingly smooth surface, such as that of a knife, to be unexpectedly rough—yet a reflection off a knife was smooth. This smoothness led Newton away from the idea of light particles physically striking the microscopically-rough surface and toward the notion of forces in the surface repelling the particles a short distance off. This idea of action at a distance, however, was anathema to the leading intellectuals of the 17th century. A few years later, in 1713, Newton would have to modify his masterpiece, Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (1687), for this very reason. In the second edition he inserted his famous disclaimer “hypotheses non fingo”: I do not feign hypotheses as to the cause of gravity, Newton claimed, but it behaves as I describe it.

In composing the first edition of Opticks, Newton sidestepped the problem of forces with a rhetorical trick. At the end of the book he appended a series of hypothetical queries. Query 1, for example, was “Do not Bodies act upon Light at a distance, and by their action bend its Rays . . . ?” To Newton the answer was obviously yes, but this way he could avoid technically committing himself. Newton warmed to this game, and in 1706, when he published the Latin edition, Optice, he added a few more queries. Then, in the second English edition in 1718 he added even more, queries that were less and less about optics and more and more about short-range forces between minute particles of bodies.

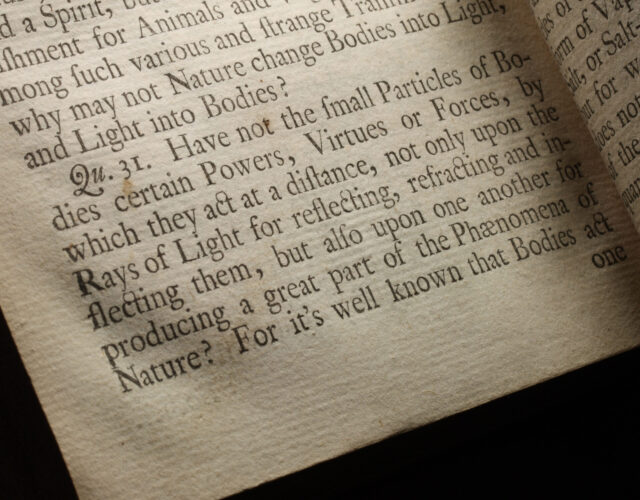

The most famous query was 31, which began “Have not the small Particles of Bodies certain Powers, Virtues or Forces, by which they act at a distance, not only upon the Rays of Light for reflecting them but also upon one another for producing a great part of the Phaenomena of Nature?” By “phaenomena of nature” Newton meant chemistry. And whereas the first set of queries had been a sentence or a paragraph, Query 31 stretched over 30 pages. Since 1669 Newton had been quietly but intensely studying chymistry (a term that denotes the sum of early chemistry and transmutational alchemy), both from books and in the lab. What he had shied away from sharing publicly now came bubbling out: deliquescence, exothermic reactions, dissolution of metals in acids, substitution reactions. He had ideas about these phenomena—the particulate structure of matter and the forces between particles—and, approaching the end of his life, he needed to get them out. The additional queries in the third edition of Newton’s Opticks marked the end of his 60-year career as a natural philosopher. So, unexpectedly, in the closing appendix to the later editions of Opticks we find Newton’s chemical legacy.