Every year, as football teams clash on the Super Bowl gridiron, corporations battle to catch the eye of millions of fans through advertisements. Fans watching the game in 1979 saw a commercial featuring a transparent “glass house” that showed “all the places insulation can save money.” The house was just a small plastic model, but the message was timely for a country still suffering through the energy crisis of the 1970s. “Put your house in the pink,” the announcer declared. “Get Owens-Corning Fiberglas insulation now; it’s cheaper than oil.”

Insulation was nothing new. Nineteenth-century builders often mixed hair from horse manes and tails into the first, “brown coat” of lime-based plaster. Straw, rags, and paper were other commonly used thermal insulators. One present-day homeowner living in a cold, snowy area near Lake Superior discovered that the walls of her 1850s house had been lined with Finnish-language newspapers. “Maybe the Finnish words are warmer than English,” she joked.

Those thrifty, long-ago immigrants had the right idea. Cellulose, the main component of wood, can be a good insulator. Wood can be processed into fibers, paper scraps, and fluff, which is then compressed into sturdy, insulating fiberboard or sandwiched between sheets of strong paper to make rolls or batts of insulation.

The spread of central heating in the early 20th century prompted homeowners to use insulation to save on fuel costs. One popular product named “Balsam-Wool” evoked the warmth of sheep’s wool, but the easy-to-install blanket (“It tucks in!”) was made of cellulose fluff and brown paper. An ad from 1929 described the insulation as an essential component of an up-to-date household: “Boiler—plus Radiators—plus Balsam-Wool—there’s a Modern Heating Equipment.”

Fiberboard and cellulose insulation products were inexpensive, but they were flammable and deteriorated when wet. Another kind of “wool” overcame these disadvantages. Iron refining left behind large amounts of useless slag. A simple but ingenious method developed in the late 19th century transformed this slag into metallic fibers known as “rock wool” or “mineral wool” (often confused with asbestos, a natural though hazardous material widely used for fireproofing in the United States until the 1980s). Workers aimed a jet of steam at molten slag as it poured from furnaces, scattering the slag into tiny pellets. As the pellets flew out of the steam like miniature comets, they grew fine, threadlike tails that hardened almost immediately. When the pellets dropped to the ground, the tails broke off and were suctioned into a chamber where workers forked them up like hay and packed them into bags for shipping.

A new type of fiber insulation appeared in the 1930s. At Corning Glass in 1932, researcher Dale Kleist was trying to join glass blocks together to create transparent, weatherproof walls. During an unsuccessful attempt to use glass as a sealant, a stream of compressed air hit the flow of molten glass, forming a spray of tiny fibers. This fortunate accident led to a 1936 patent for Fiberglas. Corning Glass soon joined with Owens-Illinois, another glass manufacturer, to found a new company dedicated to the product.

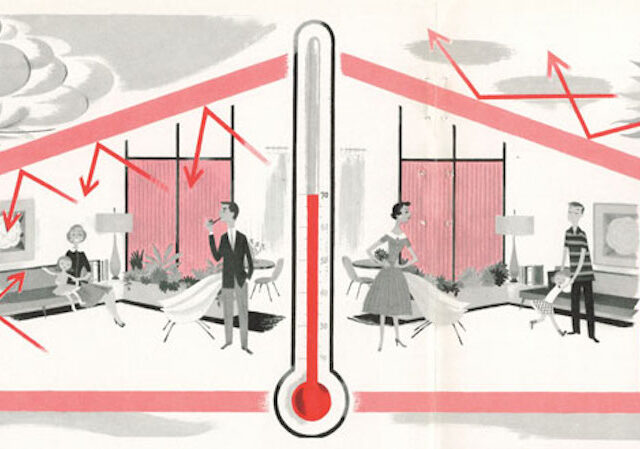

Fiberglas was economical and easy to produce in large quantities. A magazine article from 1938 proclaimed it a “new marvel of science” and explained that “a single marble, weighing only ¼-ounce, produces the incredible amount of 90 MILES of glass fiber, so finely are the threads drawn.” Owens Corning used the versatile material to reinforce plastic. The company also spun Fiberglas into thread, wove it to make cloth, and blew it into light, puffy insulation. The open-plan, air-conditioned homes popular in the 1950s could benefit from draperies, window screens, wall paneling, ceiling tiles, and insulation, all made from or with Fiberglas.

Owens Corning soon faced competition from other fiberglass manufacturers. The company began adding red dye to the naturally tan or yellowish insulation to distinguish it from their rivals’ products. Introduced in 1956, the bright pink color became such a powerful marketing tool that the company trademarked it in 1985.

PINK, in all capitals, continues to be a registered trademark of Owens Corning. The corporation even adopted the Pink Panther as a mascot in 1980. The long-legged cartoon feline, who shares his color with Fiberglas insulation, remains one of the most recognized American advertising figures.

Fiberglass today is joined by a host of other insulating materials. Styrofoam and other types of plastic foam come in many forms, from rigid panels to loose material blown into wall cavities. Rock wool is still used for thermal and acoustic insulation and for fire resistance. And eco-conscious consumers seeking to keep their homes comfortable can choose soy-foam insulation, cotton-based insulation made from recycled denim jeans, or even insulation made from genuine sheep’s wool.